References

advertisement

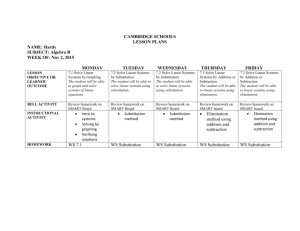

To ISSP members The methodology committee has asked the secretariat to distribute a report on substitution written by Tom Smith that was also sent to you last year. This report is not intended as an exhaustive discussion of substitution. It deals with certain important forms of substitution and their consequences and can serve as an aid in preparing for the discussion of substitution at the plenary session on Monday morning. We hope you can read this carefully before Monday. 1 Notes on the Use of Substitution in Surveys Tom W. Smith April, 2007 Substitution is a widely used (Callens and Croux, 2003; Bianchini and Loret, 1974; Lynn, 2004; Surve Sampling, 2003; Vehovar, 1999; Waksberg, 1985), but little examined, sampling method (Chapman, 1983; Rubin and Zanutto, 2002; Vehovar, 1999). Substitution designs consist of samples in which at some point during data collection nonrespondents from the initial sample are replaced with substitute cases. The literature on substitution is sparse, dated, limited, and fugitive. Most general textbooks on sampling and survey-research methods either ignore the procedure or contain only a cursory discussion (Chapman, 2003; Kish, 1965; Lessler and Kalsbeek, 1992; Little and Rubin, 2002; Lohr, 1999; Moser and Kalton, 1972l; Vehovar, 1999). When substitution is covered, sampling and survey-methodology texts usually emphasize its shortcomings. Also, several studies indicate that substitution had been disallowed, dropped or had been utilized, but was not recommended (Kordos, 2005; Linn et al., 2004; Pol, 1992; Vehovar, n.d.; Vehovar, 1999; Vehovar et al., 2002). Empirical studies of substitution all use less than optimal designs. They often use uncommon variants of substitution, do not conduct full comparisons to other methods such as continuous sampling1 with post-stratification/non-response weighting, and typically compare substitute cases to completed cases, but rarely compare 1) initial nonrespondents to their substitutes or 2) initial plus substitute completed cases to weighted completed cases without substitutes, and never compare initial plus substitute cases weighted to continued, initial cases weighted. This paper examines1) past studies comparing substitution to other sample designs, 2) various forms of substitution designs, 3) frequently mentioned advantages and disadvantages of substitution, 4) how substitution resembles other sample and study designs, 5) specific examples of substitution and non-substitution designs, 6) how substitution compares to continuous samples with weighting, and 7) the conditions under which certain forms of substitution would tend to be most useful. Past Studies Twelve studies have been identified that have done some analysis of substitution designs such as comparing substitutes to non-substitutes and evaluating alternative designs. For three of the studies only short summaries were available and the write-ups and analyses in several of the available reports were quite limited. Eleven were empirical studies and one was entirely a stimulation analysis. Two were done in the 1950s, three in the 1970s, two in the 1980s, and five in the 1990s. Six were from the US, five from Europe, and one from Japan. Of the ten empirical studies, eight used in-person interviewing and three telephone; all employed inter-unit substitution; eight substituted final units (households/individuals), one both final and intermediate units (household and respondent), and two immediate units (schools); six utilized random substitution, three were unclear, and three were non-random. 1 Continuous sample designs are those not using substitution in which initial cases are worked on a continuing basis. 2 Substitution levels were indicated for eight studies and were 5-10% for school surveys and 9-39% for household surveys Forms of Substitution Designs There are many different forms of substitution. The following five elements describe the major features of substitution designs. 1. Level: 1) intermediate or 2) lowest 2. Field Control: 1) loose/permissive or 2) tight/strict 3. Selection of substitutes: 1) random or 2) non-random 4. Matching 1) none, 2) intermediate unit (e.g. area) only, or 3) intermediate unit (e.g. area) + case-level characteristics (e.g. demographics) 5. Types of substitutes: 1) intra-household or 2) inter-household Different combinations of these produce at least several dozen types of basic substitution designs even without getting into more exotic hybrids such as using earlier cross-sections or panel designs.2 Of course some procedures are relatively rare (e.g. no matching and intra-household) and certain elements tend to be used together so certain combinations are more common than others (e.g. loose/convenience/area only and strict/random/area+demographics). First, the substitute units may be the final, target-population units (e.g. students, workers, adults) or some higher level unit used to reach the target population (e.g. schools, employers, sampling points/areas). Intermediate substitution is often used because non-response from an intermediate unit would eliminate multiple members of the target population (e.g. perhaps dozens of students in a school or employees in a company) and because the intermediate unit may not be a meaningful substantive unit in the study and as only a technical component in sampling should not be the basis for ruling out the final, target respondents (e.g. students, employees). Second, substitution can be tightly-controlled or loose (permissive). Under tight substitution, 1) substitution is used only after extensively working initial cases, 2) strict protocols exist for when substitution may be used, 3) close supervision checks that interviewers are making the required efforts and following the protocols, 4) substitute cases are chosen at random within strata, 5) when possible, initial and potential substitute cases are chosen as part of the master sample design and are matched on several variables based on information from a population register or other sample frame, and 6) the proportion of cases that are substitutes is limited (a result of following the first two points in the design of a tightly-designed use of substitution). In the most extreme case, interviewers are not even made aware that substitution is being used (Vehovar, 2003; Lynn, 2004). Third, the selection of substitutes can be done randomly or non-randomly. Random selection is usually at the initial sampling stage when clusters are drawn consisting of one initial case and typically several substitute cases. This is commonly done in school-based samples and also in household samples using sample frames 2 For drawing substitutes from nonrespondents to earlier surveys see Kish, 1965; Smith, 1983. 3 with detailed information about all units such as samples from population registers. Random sampling can also be done during the field period, but this more difficult. Systematic replacement such as taking a neighbor of a nonrespondent is not random sampling since this would lead to the relative overrepresentation of cases living next to nonrespondents and the underrepresentation of cases living next to respondents (Pol, 1992; Sirken, 1975). Non-systematic or convenience substitution is non-random and is based solely to decisions made by interviewers. Fourth, substitution may involve matching or no matching. When matching is used, it would usually be based on some intermediate unit such as area or the intermediate unit + some other known, case-level characteristics, typically demographics. Substitution almost always involves matching or substitution within sampling strata. A simple random sample design with no information about the sample units from the sample frame would be a case in which there would in effect be no individual matching or that the substitutes as a group would replace the initial nonrespodents as a group. More typical would be matching within at least an intermediate stratum, such as area codes or exchanges in RDD surveys or neighborhoods in multi-stage, area probability samples. Substitution within a geographic unit such as a neighborhood means that the initial and substitute cases share all of the aggregate, contextual variables and, to the extent that locality is important, this is a plus. If the sample frame also had case-level information on the sample units, then these could be matched on as well. This is often the case in samples based on population registers in which attributes like age and gender may be known. In effect, area, gender, and age would form strata from which initial cases and substitutes could be drawn. Finally, for household surveys, substitution could be within or between households. Within household substitution is apparently rarely done. Doing it would in most cases mean that a change in the gender of the respondent (since most two adult households contain adults of opposite gender) and would also mean an overrepresentation of multiple-adult households, since single adult households would have no within-household substitutes available (Forsman and Berg, 1992). If household-level characteristics or information on all household members being supplied from one respondent were important for the study, then using an intrahousehold substitute would be helpful. In effect in surveys with such a focus, the initial and substitute respondents are informants about the same household. (Of course, if it was a pure household-level survey, the case would be the household and any suitable household member would merely be an informant (or in effect all suitable household members are interchangeable as possible informants/”respondents”). Advantages and Disadvantages of Substitution The literature mentions several advantages and disadvantages for substitution designs. Mentioned advantages include: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Achieving more completed cases Better balance within strata in stratified samples Possible reduction in nonresponse bias Simplicity for users; self-weighting Incentive for completion of initial cases 4 Substitution typically achieves a larger sample size than continuous sample designs do and when completely successful (i.e. when a substitute is obtained for all initial cases), insures that the desired sample size is reached (Chapman, 1983; Elteto, 2003; Lessler and Kalsbeek, 1992; Moser and Kalton, 1972; Nathan, 1980; Vehovar. 1999). This can especially be useful when contracts specify a certain minimal number of cases to be completed (Waksberg, 1985). If substitution eliminates or reduces added variance from weighting, it will also produce a larger effective sample size (Biemer, Chapman, and Alexander, 1985). Likewise, in stratified samples better balance across strata is typically achieved by substitution (Chapman, 1983; Survey Sampling, 2003). However, not all substitution surveys succeed in interviewing substitutes for all initial cases and others need to go through multiple substitutes per case to cover all initial cases, which lowers the response rate (see below in disadvantages). To the extent that substitutes more closely resemble initial nonrespondents (for whom they are substitutes) rather than initial respondents, substitution will reduce nonresponse bias (Chapman, 2003; Lessler and Kalsbeek, 1992; Rubin and Zanutto, 2002; Vehovar, 1999). This is discussed further below. If substitution is complete and there is no need for a design-based weight (e.g. due to an oversample or interviewing only one respondent per household) and no use of other weights (e.g. post-stratification), then substitution may produce a simpler design with no need to weight (Chapman, 1983 & 2003; Vehovar, 1999). However, most designs and implementations of them do require a weight even if substitution is used, so this advantage is not common. In addition, methods for both creating and applying weights have become easier over time and avoiding weights is less beneficial than previously. It is often argued that the use of substitution leads to initial cases being worked less vigorously (see disadvantages below), but Moser and Kalton (1972) based on Gray and Corlett (1950) advance the argument that interviewers will be more diligent in obtaining interviews from initial cases since they know that they will still have to obtain an interview from a substitute case and have to start from scratch with the substitute case. Mentioned disadvantages include: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. Lower response rate False or misleading response rate/ignoring true response rate No reduction/increase in nonresponse bias Difficulty of having/maintaining field controls Longer field period Substitution incomplete Substitution non-random With a similar total level of effort, the nonresponse rate may be higher in substitution surveys even before substitution itself is taken into consideration, because less effort will be devoted to the initial cases (Chapman, 1983; Chapman and Roman, 1985; Elliot, 1993; Lohr, 1999; Rubin and Zanutto, 2002; Vehovar, 1999). Substitution will probably yield more cases than non-substitution designs with a similar level of effort (because the former will pick up more easy cases than the other adds hard cases). Of course once substitution is correctly accounted for, the response 5 rate would be expected to fall since nonrespondents among the substitutes will be added to the initial nonrespondents. It will fall appreciably if multiple substitutes are used to secure a replacement for all initial nonrespondents. Say for example, that the initial response rate was 50% and an average of 2.5 cases were needed to fill all substitute cases. That would lower the final response rate to 44.4% and an average of 3.0 substitutes per initial nonrespondent would mean a response rate of 40.0%. The discussion below on cases of study designs elaborates further on this point. Several studies also show that substitutes have a lower response rate than initial cases (Biemer, Chapman, and Alexander, 1985, Callens and Croux, 2003; Vehovar, 1993). In some cases this appears to merely result from substitute cases being worked less hard (e.g. for a shorter field period). However, to the extent that substitutes represent initial nonrespondents rather than all initial cases, a lower response rate would be expected and might be seen as a sign that the substitutes were representing the initial nonrespondents. Substitution is sometimes used to mask or miscalculate response rates (Chapman, 1983; Lessler and Kalsbeek, 1992; Nathan, 1980; Vehovar, 1999). Standard Definitions: Final Disposition of Case Codes and Outcome Rates for Surveys (2006) of the American Association for Public Opinion Research and World Association for Public Opinion Research stipulates how response rates using substitution should be calculated. In essence, all initial nonrespondents and all nonrespondents among substitutes must remain in the base. Also according to these standards, the level of substitution used in a survey needs to be separately reported. Substitution may be less likely to reduce nonresponse bias than a continuous design (Chapman, 1983; Elliot, 1993; Kish, 1965; Lessler and Kalsbeek, 1992; Little and Rubin, 2002; Moser and Kalton, 1972; Rubin and Zanutto, 2002; Smith, 1983). Moser and Kalton (1972) state that “If substitutes are taken, all that happens is that nonrespondents are replaced by respondents, so the risk of bias remains the same.” Williams and Folsom (1976) and Durbin and Stuart (1954) found the substitute samples to be biased; Marlini and Pacei (1993) and Williams and Folsom (1976) concluded that substitutes did not closely resemble the initial nonrespodents they replaced; and Sirken (1975) showed that substitutes were more like initial respondents than initial nonrespondents. Vehovar (2003) describes the idea that substitutions outperform weighting adjustments as “never proven.” Apparently only two studies have compared substituting with continuous surveying using nonresponse/post-stratification weighting. One found more bias from substitution than weighting (Biemer, Chapman, and Alexander, 1985; Chapman and Roman, 1985). The other concluded that substitution provides “no improvement in nonresponse bias in comparison to the alternate weighting adjustment” (Vehovar, 1993). The final achieved sample in a substitution design may well be less like the complete target sample because it will have fewer very difficult cases than a design that expends all efforts on only the initial sample and then weights for nonresponse since the later will include more difficult cases and these will be weighted up along with easier cases.3 However, both approaches will underrepresent difficult cases. 3 Scheuren (2004) has recently reprinted for consideration a design by Kish and Hess (2004) that used noncontacts from previous surveys as substitutes for noncontacts in a subsequent survey and which proposed that similar substitution could be done with refusals. This has the potential for making the substitutes less like initial cases and more like the cases they are replacing. However, this version of substitution is rarely, if ever, used. 6 Field control is always difficult in decentralized designs such as multi-stage, area probability samples and this is even more challenging when substitution is employed (Vehovar, 1999). Interviewers must follow protocols for the initial cases, for when substitutes can be used, and then for handling the substitute cases. Moreover, it is commonly assumed that interviewers want to drop difficult initial cases and try potentially easier substitute cases (Chapman, 2003; Chapman, 1983; Chapman and Roman, 1985; Lessler and Kalsbeek, 1992; Lohr, 1999; Vehovar, 1993). There is a motivation to both not vigorously pursue initial cases and to prematurely switch to substitutes. However, Sudman (1967) in a comparison of block quota and full probability surveys found that interviewers did not slack-off in their pursuit of cases even though “substituting” cases was fully acceptable under quota rules and, as noted above, Durbin and Stuart (1954) argue that substitution motivates more efforts on initial cases. Most descriptions of substitution designs fail to mention either field control procedures or success in carrying them out. Rigorous substitution designs first work initial cases for an extended period and then devote a similar extended effort to securing the substitute cases. This might well lead to the lengthening of the total field period (Rubin and Zanutto, 2002; Vehovar, 1999; Waksberg, 1985). Of course, a continuous design might continue to pursue initial cases for just as long as in a substitution design. Alternatively, a substitution design could also be set up to go no longer than a period used for a continuous design, but that would mean working initial cases and substitute cases for less time than cases in a continuous design covering the same time span. Substitution is usually assumed to be complete, but this is often not the case (Chapman, 1983). In substitution surveys coverage sometimes falls well short of the target. For example, in the National Health Interview Survey/RDD Feasibility Study substitutes were secured for only 65% of initial cases (Chapman and Roman, 1985). Likewise, a school-based study of students was able to get substitute schools for just 41% of initial nonrespondents (Williams and Folsom, 1976). Incompleteness reduces several of the proffered advantages of substitution mentioned above. Substitution may be non-random (Chapman, 1983). While not used in an optimal substitution design, this is utilized in some substitution designs and this clearly means that a full-probability sample has not been followed. Resemblance of Various Forms of Substitution to Other Designs The nature of various substitution designs can be clarified by considering in what ways they resemble and in what ways they differ from alternative, nonsubstitution designs: 1. Low Response Rate, Continuous Designs: A large probability sample with a low response rate and few callbacks is like an uncontrolled and unmatched, but randomized, substitution design. In such a continuous design extra cases are included from the start and are like aggregate replacements for lightly worked initial cases and remain nonrespondents as opposed to the sequential and case-linked replacements used in substitution designs. 2. Replicates: The use of replicates may seem like substitution, but the additional sample is released for purposes other than compensating and adjusting for nonresponse, such as to avoid not issuing more sample than is needed (and thus to minimize expenses, to sample time more evenly in studies with long field period, and maintain a higher response rate), or to manage the flow of cases. The use of replicates 7 does not involve linked cases (initial and substitute) and usually does not mean that efforts to interview active cases from the initial or earlier replicates are abandoned when later replicates are released. Replicates augment the sample and do not replace cases. 3. Quota Samples: Quotas samples resemble substitution in that there is substitution and that quota controls bear some resemblance to the matched controls typically used in substitution (Smith, 1983). The resemblance is even closed when substitution does not use a random selection of substitution cases. If the quotas are multivariate (e.g. say using an 8-fold classification of gender (2) * white/not-white (2) * under/over 40 years old), then the substituting and quotas as very similar. If the quotas are only distributional (e.g. so many men/women, whites/non-whites, old/young), then there is greater difference between them. They differ in that there is not really any initial cases in quota samples (there are simply cases approached sooner or later in the process of securing respondents), that the quota controls are in the aggregate and do not represent matching across specific cases, and that the total number of cases touched is likely to be greater with quotas than with substitution except for the use of the loosest set of substitution rules (e.g. indiscriminate substitution). The literature on substitution often assumes that very elaborate versions are being used. For example, that field periods are longer because the substitute cases are being released only after initial cases have been extensively worked and then the substitute cases themselves are worked for an extended period. But in actuality, substitution appears to be often used as a quicker and less expensive method. In this situation, substitution is done early and often and substitutes are selected on the basis of convenience rather than randomly. Under such a substitution design a main aim is completing a target number of cases as rapidly and easily as possible. As such, permissive use of substitution more closely resembles quota sampling with either matching acting like quota controls or with little or no matching except on sampling point so there is little or none of the control for demographics that quotas provide for. 4. Household Proxies: Using household proxies is like within household substitution. They are essentially the same when the survey deals with householdlevel information or information about all household members. For respondent-level information the initial respondent remains the same, but the information about that person is supplied by the proxy, while in substitution the initial target respondent is replaced by the substitute respondent (Boyle and Brann, 1992). 5. Household Informants: When the unit is the household or for collecting information on all household members and any eligible household member can provide that information, then there is no initial respondent and selecting an informant would closely resemble within household substitution. The difference is that there is no formal substitution and no collection of respondent-only information, but that all eligible household members are potential informants and interchangeable for one another. Examples Comparing Response Rate/Number of Cases for Various Designs To further compare substitution to other sample designs, Table 1 examines one substitution design and five non-substitution designs. In these examples the initial sample is always 2000 and neither in the initial sample nor in any of the added sample are any of the cases out-of-scope. Also, all examples have the same result after 8 8 weeks, 1000 completed cases and a provisional response rate of 50%. The differences are in how the rest of the field effort is handled. Case A is a standard, continuous approach with no changes in design after phase one (eight weeks). In effect, there is no phase one and phase two, just one continuing effort. All cases are worked until they become completed cases or are classified as nonrespondents either during the field period or at its conclusion. In this example, an additional 400 interviews are secured for a final sample size of 1400 and a response rate of 70%. Case B uses a full-substitution design in which the 1000 nonrespondents at the end of phase one are replaced by 1000 substitute cases. Since they are matched on area and perhaps some other characteristics with the nonrespondents from phase one, it is assumed that their response rate will be lower than a random sample of respondents and nonrespondents. A new sample of the whole target population worked to the same field period would be expected to yield the same result as the initial sample (50% response rate). To the extent that the matching or stratifying characteristics are related to nonresponse, the substitute sample would be expected to yield a lower response rate. Here the assumption is the matching is a fairly weak predictor, so there is only a 10% loss in productivity (yielding 450 cases instead of 500) and a final sample size and response rate of 1450/48.3%. If the sample cases were much more like the dropped phase one nonrespondents, then the yield would be less. Case C is an unusual design in which a replicate of 800 is issued for phase two and work ceases on the phase one nonrespondents. It has a response rate of 50% phase one, phase two (since the field period and sample population are the same), and overall. It yields 1400 cases (1000+400). Case D is the more typical replicate design in which a sample of 400 representing the whole target sample is added and the 1000 phase one cases are continued to be worked. After phase two the replicate has yielded 200 cases (50% response rate) and the 1000 continued cases have yielded 200 cases. This yield is lower than in case A. The difference is because the assumption is that the effort devoted to the replicate had to be diverted from working the initial cases, that is that the total field effort was not expanded, but divided among two efforts. The final achieved sample size is 1400 and the response rate 58.3%. Case E is a hybrid substitution/continuation design in which 500 of the nonrespondents at the end of phase one are dropped and substituted for and 500 are continued. The 500 substitute cases are assumed to yield 225 (the same 90% effectiveness assumption as in Case B). The 500 cases not substituted for are assumed to yield 200 cases (the same rate as in Case A). That yields a final total of 1425 cases (1000 initial cases from phase one + 225 substitutes + 200 cases from the replicate) and a response rate of 57.0%. Case F takes the 1000 nonrespondents at the end of phase one and subsamples them, dropping 500 and retaining 500. It is assumed that half of the 500 remaining are interviewed by the end of phase two. Since each of these cases represents two cases (due to the subsampling), they are weighted up to make 500 cases for purposes of both calculating the response rate and substantive analysis for a weighted total of 1500 and a response rate of 75%. Of course the effective sample size is lower than 1500 (1250 – design effects due to weighting) and this would have to be taken into consideration in inferential statistical comparisons. Also, note that the yield of 50% for the phase two cases is higher than the assumed yield of 40% for Case A. This is based on the assumption that by reducing the scope of work (from following up 500 9 cases to following up 250) more effort could be devoted per case. Among other things this might also mean using only the best interviewers from phase one during phase two. Substitution and Nonresponse/Post-stratification Weighting Nonresponse and post-stratification weighting assumes that non-respondents are MCAR within the weight categories. That in effect means that within categories the respondents and non-respondents are the same. Substitution assumes that the substitutes resemble nonrespondents (e.g. original, non-interviewed cases) and not respondents from the initial sample. Both assumptions are usually problematic and at best only partly correct. Weighting reduces nonresponse bias to the extent that the weight categories are correlated with nonresponse bias. They usually are correlated to some extent, but often the relationship is not strong. Weighting then assumes that within weighting categories nonrespondents are MCAR or in other words that they are the same as respondents. This is a dubious assumption since the one thing that is known about the nonrespondents and respondents within categories is that they differ in their response status. Substitutes resemble the initial nonrespondents to the extent they are matched on variables selected for selecting substitutes. The matching variables are similar in function to the weighting categories used in nonresponse/poststratification weights in non-substitution designs (Elliot, 1993). However, within the matched groups, the substitute cases are equivalent to all initial cases, not to initial nonrespondents alone. Furthermore, it is likely that those substitutes that become respondents within matched groups will be more like initial respondents than nonrespondents since they share the characteristic of doing an interview and differ from initial nonrespondents who did not do an interview. By working cases longer and harder the continuous sampling + nonresponse/post-stratification approach should yield a higher response rate and have more hard cases among the completed cases than does substitution. This would suggest that weighting might reduce nonresponse bias more than substitution because there would be less difference between respondents and nonrespondents or in other words that the completed cases would better represent the nonresponse cases and thus the target population (Biemer, Chapman, and Alexander, 1985). Also, in most cases the range of variables known about cases from a sample frame is fairly limited and will not necessarily be good predictors of nonresponse bias. There would usually be more variables to choose from in developing a nonresponse/post-stratification weight and they could usually be selected because of how well they modeled nonresponse bias. Another factor to consider is that compared to substitution, nonresponse/poststratification weights increase the sampling variance and underestimate the population variance. When complete substitution is achieved, this reduces sampling variance (larger N and no extra variance from a weight) and increases true variance (substitutes are more variable than taking existing cases and weighting them up or down) and this better reflects the real variability of the target population. If substitution can avoid the use of weights or at least have weights with less variance, then substitution designs would have a greater effective sample size for a given number of actual cases. Finally as Chapman (1983) has noted, “All (empirical studies) seemed to indicate that substitution procedures do not eliminate the effects of nonresponse bias (but) it is probably true there is no procedure available that can adequately correct nonresponse bias.” As he has further noted (Chapman, 2003), “(T)he fundamental question is 10 whether it is better to use a substitute unit for a survey nonrespondent, rather than imputing nonrespondent data from a blend of the data reported by respondents in the same weighting class.” Conditions under which Substitution is More Useful Substitution designs would tend to overcome some of the noted disadvantages and achieve advantages under various conditions: 1. Having a sample frame with considerable information on the sample unit: European sample frames based on population registers with certain household and/or respondent-level demographic information are generally more suitable for substitution designs than area probability designs such as used in the US with little or no household/respondent information in the sample frame. It is particularly advantageous if the known attributes of cases are correlates of nonresponse. 2. Stratified samples rather than SRS designs: Even if little is known about the sample cases, the use of strata in the sample would allow substitution within strata such as neighborhoods within a multi-stage, area, probability design. Since locality is often related to response rates (e.g. lower in cities and higher in small town and rural areas) and neighborhoods typically differ on other variables such as SES and race/ethnicity, within strata weighting and/or substitution have the potential to reduce nonresponse bias. 3.Centralized vs. decentralized designs: Field control is difficult for all area probability designs in which interviewers are dispersed to many sample points and not under direct observation and substitution designs increase this problem by both making field procedures more complex and providing an incentive to flout the rules. For example, interviewers may give up on hard cases and switch to substitutes either without all protocols being followed (e.g. number of call attempts) or by exercising less effort per attempt to secure interviews from the initial cases. Centralized designs, such as CATI surveys from a call center, are much more subject to strict control and thus mostly eliminate this problem (Biemer, Chapman, and Alexander, 1985). Moreover, it is even more desirable if interviewers are not even aware that substitution is being used (Lynn, 2004; Vehovar, 2003). Conclusion With optimal substitution - using close field supervision, full-efforts for both initial cases and substitutes, randomly-selected substitutes, etc., substitution resembles the use of random replicates and should probably be considered a full-probability design. The use of close control, random selection of substitutes, and full efforts to obtain initial cases leading to limited use of substitution are key design factors that make substitution a method for adjusting for nonresponse bias within a fullprobability framework rather than being a non-probability design as with volunteer, convenience, and quota samples (Chapman, 1983; Lessler and Kalsbeek, 1992; Lohr, 1999; Rubin and Zanutto, 2002). Some substitution designs no more deviate from an ideal, full-probability design than do the use of nonresponse/post-stratification weights to compensate for nonresponse bias. Counter to what Lynn et al. (2004) asserts, it is not true that across substitution designs that “none of them meet the 11 requirement for probability sampling.” Neither well-executed continuous designs nor optimal substitution designs achieve idealized full-probability standards (no over- or undercoverage, no nonresponse bias, etc.), but both can produce creditable, practical approximations of full-probability surveys. It is less clear whether optimal substitution produces equivalently effective adjustments for nonresponse bias as does weighting. Theoretical expectations tend to favor weighting as superior to substitution and some empirical studies back this conclusion. But there are too few well-designed, comparative studies of the two approaches and none that apparently compare substitution + weighting to continuous interviewing + weighting to be confident in this as a general outcome. Clearly more research is needed to test how optimal substitution designs compare to continuous sampling designs and whether weighting the latter or both produces the best estimates and what weighting does to effective sample size (Chapman, 1983; Groves et al., 2002; Scheuren, 2004). At least in simulation studies, Rubin and Zanutto (2002) find matched substitutes with multiple imputations to be a useful approach that is as good as or better than other common designs. Whether empirical studies will support this conclusion is an open question. Only careful experimental comparisons of well-designed and executed substitution and continuous design will definitively establish the relative merits of the two approaches. 12 Table 1 Examples of Outcomes Using Different Designs Design Starting Sample Added Sample Completed Cases/ Response Rate 8 weeks 16 weeks A. No Substitution 2000 None 1000/50% B. Full Substitution 1450/48.3% 2000 1000 1000/50% C. Replicate/Discontinue 2000 800 1000/50% D. Replicate/Continue 1400/58.3% 2000 400 1000/50% E. Substitute/Continue 2000 500 1000/50% 1425/57% None 1000/50% 1500/75% F. No Substitute/Sub-Sample 2000 13 1400/70% 1400/50% References American Association for Public Opinion Research, Standard Definitions: Final Disposition of Case Codes and Outcome Rates for Surveys. Lenexa, KS: AAPOR, 2006. Bianchini, John C. and Loret, Peter G., Anchor Test Study: Final Report. Berkeley: Educational Testing Service, 1974. Biemer, Paul; Chapman, David W.; and Alexander, Charles, “Some Research Issues in Random-Digit Dialing Sampling and Estimation,” in Proceedings, First Annual Research Conference March 20-23, 1985. Washington DC: Bureau of the Census, 1985. Boyle, Coleen A.; and Brann, Edward A., “Proxy Respondents and the Validity of Occupational and Other Exposure Data,” American Journal of Epidemiology, 136 (1992), 712-721. Callens, Marc and Croux, Christopher, “Nonresponse in the Belgium Fertility and Family Survey,” Unpublished report, Population and Family Study Center, Belgium, 2003. Chapman, David W., “The Impact of Substitution on Survey Estimates,” in Incomplete Data in Sample Survey, edited by William G. Madow, Ingram Olkin, and Donald B. Rubin. Volume 2. New York: Academic Press, 1983. Chapman, David W., “To Substitute or Not to Substitute – That is the Question,” The Survey Statistician, 48 (2003), 32-34. Chapman, David W. and Roman, Anthony M., “An Investigation of Substitution for an RDD Survey,” in 1985 Proceeding of the Section on Survey Research Methods. Washington, DC: American Statistical Association, 1985. Durbin, J. and Stuart, A,, “Callbacks and Clustering in Sample Surveys: An Experimental Study,” Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, Series A (1954), 387-410. Elliot, Dave, “The Use of Substitution in Sampling,” Survey Methodology Bulletin, 33 (July, 1993), 8-11. Elteto, Odon, “Substitution in the Hungarian HSB,” The Survey Statistician, 49 (2004), 16-17. 14 Forsman, Goesta and Berg, Sven, “Telephone Interviewing and Data Quality: An Overview and Empirical Study, Unpublished report, Institute of Technology, Linkoeping University, 1992. Gray, P.G. and Corlett, T., “Sampling for the Social Survey,” Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, A, 113 (1950), 150-206. Jay, Gina M.; Liang, Jersey; Liu, Xian; and Sugisawa, Hidehiro, “Patterns of Nonresponse in a National Survey of Elderly Japanese,” Journal of Gerontology, 48 (1993), S143-S152. Kalton, Graham and Kasprzyk, Daniel, “The Treatment of Missing Survey Data,” Survey Methodology, 12 (1986), 1-16. Kish, Leslie, Survey Sampling. New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1965. Kish, Leslie and Hess, Irene, “A ‘Replacement’ Procedure for Reducing the Bias of Nonresponse,” American Statistician, 58 (2004), 295-297. Excerpt from American Statistician, 13 (1959), 17-19. Kordos, Jan, “Household Survey in Transition Countries,” in Household Sample Surveys in Developing and Transition Countries, edited by United Nations. Studies in Methods, Series F, No. 96. New York: UN, 2005. Lessler, Judith T. and Kalsbeek, William D., Nonsampling Error in Surveys. New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1992. Little, Roderick J.A. and Rubin, Donald B., Statistical Analysis with Missing Data. 2nd edition. New York: John Wiley & Sons, 2002. Lohr, Sharon L., Sampling: Design and Analysis. Pacific Grove, CA: Duxbury Press, 1999. Lynn, Peter, “The Use of Substitution in Surveys,” The Survey Statistician, 49 (2004), 14-16. Lynn, Peter; Haeder, Sabine; Gabler, Siegfried; and Laaksonen, Seppo, “Methods for Achieving Equivalence of Samples in Cross-National Surveys: The European Social Survey Experience,” ISER Working Paper, 2004-09, 2004 Marliani, Gianni and Pacei, Silvia, “Effects of Household Substitution in the Italian Consumer Expenditure Survey,” Bulletin of the International Statistical Institute. Firenze: ISI, 1993. Moser, C.A. and Kalton, G., Survey Methods in Social Investigation. New York: Basic 15 Books, 1972. Nathan, Gad, “Substitution for Non-response as a Means to Control Sample Size,” Sankhya, 42 (1980), 50-55. Pol, Louis G., “A Method to Increase Response When External Interference and Time Constraints Reduce Interview Quality,” Public Opinion Quarterly, 56 (1992), 356-359. Rubin, Donald B. and Zanutto, Elaine, “Using Matched Substitutes to Adjust for Nonignorable Nonresponse through Multiple Imputations,” in Survey Nonresponse, Robert M. Groves, Don A. Dillman, John L. Eltinge, and Roderick J.A. Little. New York: John Wiley & Sons, 2002. Scheuren, Fritz, “Introduction,” American Statistician, 58 (2004), 290-291. Smith, Tom W., “The Hidden 25 Percent: An Analysis of the 1980 General Social Survey,” Public Opinion Quarterly, 47 (1983), 386-404. Sudman, Seymour, Reducing the Cost of Surveys. Chicago: Aldine, 1967. Survey Sampling International, “Random Digit Telephone Sampling Methodology,” 2003. Vehovar, Vasja, “Field Substitution and Unit Nonresponse,” Journal of Official Statistics, 15 (1999), 335-350. Vehovar, Vasja, “Field Substitutions – A Neglected Option?” Unpublished paper, University of Ljublijana, n.d. Vehovar, Vasja, “Field Substitution in Sample Surveys: The Case of the Slovenian Labour Force Survey,” Bulletin of the International Statistical Institute. Firenze: ISI, 1993. Vehovar, Vasja, “Filed Substitutions Redefined,” The Survey Statistician, 48 (2003), 3537. Vehovar, Vasja; Zaletel, Metka; Novak, Tatjana; Arnez, Marta; and Katja, Rutar, “Household Sample Surveys in Slovenia,” Statistics in Transition, 5 (2002), 671-685. Waksberg, Joseph, “Discussion,” in Proceedings, First Annual Research Conference March 20-23, 1985. Washington DC: Bureau of the Census, 1985. Waksberg, Joseph, “Sampling Methods for Random Digit Dialing ,” Journal of the American Statistical Association, 73 (1978), 40-46. Williams, Stephen R. and Folsom, Ralph E., Jr., “Bias Resulting from Nonresponse: 16 Methodology and Findings. Revised,” Technical Report on NLS Base-Year Estimates, RTI, September, 1976. 17 Current practice – Recommendations from the ISSP General Meeting 2003 a. The use of substitution is discouraged since i) in its looser forms it may notably deviate from full-probability designs and risk becoming a convenience sample that overrepresents easy-to-contact and compliant respondents and ii) its use may lead interviewers to reduce their efforts to obtain interviews from the originally selected units/persons. b. The MC should collect more detailed information on exactly how substitution is used including the conditions under which substitutions may be utilized, whether substitution is at the interviewer's discretion or only authorized by the central office, whether substitute units are pre-selected, number of substitutions, etc. c. After this review the Methodology and Standing Committees will further consider the use of substitution. d. The total number of cases which are substitutions must be reported. In each data file all substitute cases should be marked with a flag variable. e. All replaced cases must be counted as non-respondents. For example, consistent with the AAPOR/WAPOR standards, "if a household refuses, no one is reached at an initial substitute household, and an interview is completed at a second substitute household, then the total number of cases would increase by two and the three cases would be listed as one refusal, one no one at residence, and one interview." 18