A Guide to Contextual Learning Projects

advertisement

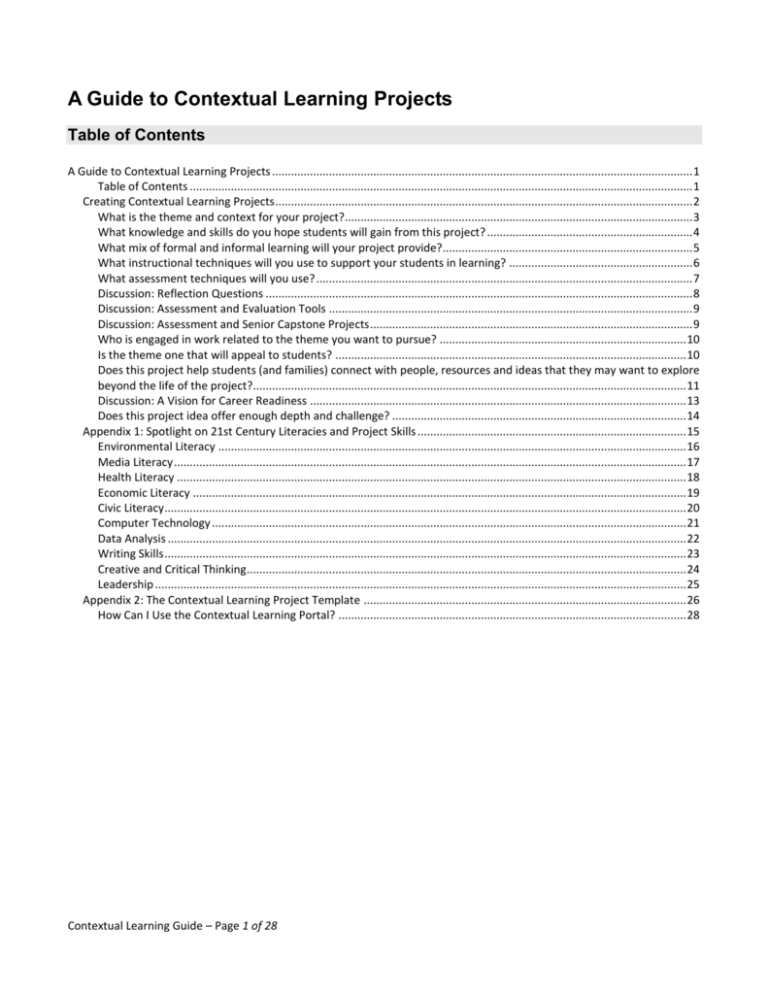

A Guide to Contextual Learning Projects Table of Contents A Guide to Contextual Learning Projects ..................................................................................................................................... 1 Table of Contents ............................................................................................................................................................... 1 Creating Contextual Learning Projects .................................................................................................................................... 2 What is the theme and context for your project?.............................................................................................................. 3 What knowledge and skills do you hope students will gain from this project? ................................................................. 4 What mix of formal and informal learning will your project provide? ............................................................................... 5 What instructional techniques will you use to support your students in learning? .......................................................... 6 What assessment techniques will you use? ....................................................................................................................... 7 Discussion: Reflection Questions ....................................................................................................................................... 8 Discussion: Assessment and Evaluation Tools ................................................................................................................... 9 Discussion: Assessment and Senior Capstone Projects ...................................................................................................... 9 Who is engaged in work related to the theme you want to pursue? .............................................................................. 10 Is the theme one that will appeal to students? ............................................................................................................... 10 Does this project help students (and families) connect with people, resources and ideas that they may want to explore beyond the life of the project?......................................................................................................................................... 11 Discussion: A Vision for Career Readiness ....................................................................................................................... 13 Does this project idea offer enough depth and challenge? ............................................................................................. 14 Appendix 1: Spotlight on 21st Century Literacies and Project Skills ..................................................................................... 15 Environmental Literacy .................................................................................................................................................... 16 Media Literacy .................................................................................................................................................................. 17 Health Literacy ................................................................................................................................................................. 18 Economic Literacy ............................................................................................................................................................ 19 Civic Literacy ..................................................................................................................................................................... 20 Computer Technology ...................................................................................................................................................... 21 Data Analysis .................................................................................................................................................................... 22 Writing Skills ..................................................................................................................................................................... 23 Creative and Critical Thinking ........................................................................................................................................... 24 Leadership ........................................................................................................................................................................ 25 Appendix 2: The Contextual Learning Project Template ...................................................................................................... 26 How Can I Use the Contextual Learning Portal? .............................................................................................................. 28 Contextual Learning Guide – Page 1 of 28 Creating Contextual Learning Projects Contextual learning projects engage students in academic work applied to a context related to their lives, communities, workplaces or the wider world. Projects may range in length from a single class period to a semester-long exploration. Projects may take place in after-school or summer programs or in workbased learning programs as well as in a regular classroom. This guide explores ideas and principles for creating contextual learning projects. We hope this guide is useful to you, whether you are experienced in contextual learning, and looking for ways of deepening and enriching your work or whether you are just beginning to explore the design of contextual learning projects. We also hope it is useful whether you are already an enthusiastic supporter of contextual learning or whether you are just looking at whether contextual learning is right for your school or program and weighing the pros and cons of this approach to learning. This guide is based on the Contextual Learning Portal, a website – http://resources21.org/cl -- that provides an informal database of projects submitted by teachers, after-school program leaders and others from around Massachusetts. On the Contextual Learning Portal website, viewers can browse projects by project title, subjects, tags, frameworks, keywords or other criteria. Viewers can look at entire projects or can browse particular sections from the “project template” such as project themes, instructional techniques or assessment techniques. The Contextual Learning Portal uses a project template that includes seven tabs with information about the project. This template is flexible and allows users to modify or omit sections as needed. 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. Basics: Basic information about the project, including project title, theme, subject areas involved, team members, technical support required, and any adaptations required; Key Questions: Questions about the context of the project, including the “key questions” addressed by the project, connections to the community, and outcomes, products or services provided to the community; Frameworks and skills used; Units / Activities included in the project; Instructional Techniques used in the project; Assessment Techniques used in the project; Tags (such as “History” or “Careers” or “Service-Learning” or “Literacy”) to help viewers find the project. The Contextual Learning Portal was created as a space for school districts, community organizations, non-profit educational groups, and other youth serving agencies to share projects and lessons to support contextual teaching and learning for both teachers and learners. Teachers, youth program instructors and others are welcome to browse and contribute projects. Visit the Contextual Learning Portal at http://resources21.org/cl This guide walks through various aspects of planning and implementing contextual learning projects, starting with basic questions about getting started and then examining questions about “looking deeper” to make sure that contextual Contextual Learning Guide – Page 2 of 28 learning projects are effective. The guide includes an appendix with profiles of some of the skill areas and areas of focus – such as health literacy, environmental literacy and civic awareness – often explored in contextual learning projects. Getting Started: What is the theme and context for your project? What knowledge and skills do you hope students will gain from this project? What mix of formal and informal learning will your project provide? What instructional techniques will you use to support your students in learning? What assessment techniques will you use? Looking Deeper: Who in your school and community is engaged in work related to the theme you want to pursue? Does this project help students (and families) connect with people, resources and ideas that they may want to explore beyond the life of the project? Is the theme one that will appeal to students? Does this project idea offer enough depth and challenge to let students exercise essential skills in areas such as critical thinking, creative thinking, writing, data analysis, scientific observation or leadership? What is the theme and context for your project? Contextual learning projects engage students in academic work applied to a context related to their lives, communities, workplaces or the wider world. In the Contextual Learning Portal, common themes include: History Environment Nutrition and health Gardening and food Career exploration School climate and anti-bullying Arts, literacy, books and reading The context for the project may be workplace-based, community-based or school-based. Examples include: Writing for a school newspaper; Developing videos, websites, handbooks or brochures about a topic; Developing lesson plans and learning materials for younger students; Participating in an environmental advocacy campaign; Conducting field studies in wetlands or salt marshes; Writing a business plan in a entrepreneurship program; Creating exhibits for a local history museum. The process of choosing a theme and context for a project can start anywhere. It can start with a set of learning goals (such as a desire to help students explore health topics; get experience in web design; explore math skills; or gain experience writing for various audiences) or it can start with student, teacher or community partner suggestion of a project and a topic of study. Contextual Learning Guide – Page 3 of 28 What knowledge and skills do you hope students will gain from this project? Contextual learning projects often emphasize research, writing and presentation skills. For example, students might research an issue in the community and make a presentation about their findings at a city or town meeting. Students might create informational materials about a topic of interest to the community, such as health, nutrition, traffic, parking or local economic development. Students might develop a video, a website, a podcast, or other media to communicate about their topic. Contextual learning projects also often emphasize math skills, including basic applied math, data analysis, and higher-order math. Students might apply data analysis, graphing and statistical skills to gathering data or analyzing survey results for a community project. Students might apply business math skills to an entrepreneurial project. Higher-level algebra and geometry can be explored as well, such as using algebraic formulas or geometric grids in a computer programming project, or exploring the math used in an environmental, physics or engineering project. Along with research, writing, presentation and math skills, contextual learning projects often build lifelong learning skills and lifelong “literacies” including health literacy, environmental literacy, economic literacy, media literacy and civic literacy. Certain academic subjects are especially likely to provide contexts for contextual learning projects, particularly history, health and biology/ecology. Career vocational/technical subjects provide frequent contexts for community-based and workplace-based projects, using skills in carpentry, horticulture, computer technology, graphic design, engineering technology and more. Math and Contextual Learning. Students can apply both basic and higher-level math skills in projects, including projects that include analyzing data, business planning, building and pattern-making, working with maps, working with spreadsheets and graphing software, exploring physics and engineering, and using math in computer programming and web design. Interdisciplinary Learning Opportunities: The Park Stewards Program at the New Bedford Whaling National Historical Park, featured in the Contextual Learning Portal, offers a very rich multidisciplinary learning opportunity. Workplace experiences frequently provide opportunities for building academic knowledge and skills as well as career skills and career awareness. For example, students working in summer internships in a museum or zoo may create new exhibits or display boards for visitors, applying research, writing and illustration skills to the task. Students working in a day care center, day camp or nursing home activities program may design new activities, including researching, writing and teaching the activity. Students working in a health club may read about exercise programs and learn about how new members are oriented to the health club activities. Students working in a bank may learn to create spreadsheets for analyzing financial information. Internships in media, journalism, the arts, engineering, technology, healthcare, education, childcare, retailing, environment, agriculture and multiple other fields provide valuable exposure to applied academic skills and career skills. Contextual Learning Guide – Page 4 of 28 The Contextual Learning Portal is organized around checklists of the curriculum frameworks, 21 st century skills framework and other skill sets and frameworks, allowing viewers to browse projects by frameworks and skills used. As of May 2012, there are 234 projects in the portal, with the average project touching on two or more subject areas: Subject Area English Language Arts Math Science Technology History Total Projects Number of Projects 139 118 98 81 56 234 Contextual Learning Projects often take an interdisciplinary approach to topics of interest: Ecological Explorations Webster Public Schools Community Garden Westfield Public Schools “Postcards” History Project Malden Public Schools What mix of formal and informal learning will your project provide? Students need both formal and informal learning experiences for healthy intellectual development. Informal learning experiences form a context that supports brain development and language acquisition, as well as forming a context for understanding science, literature, history, math, and other subjects. For example, students who spend time playing with building sets, gears, wheels, levers and pulleys have a better foundation for understanding engineering and physics concepts. Students who have spent time hiking, gardening or exploring the shore of a lake, river or ocean have a better foundation for learning biology. Students who have participated in local community action projects have a better foundation for studying history and civics. Informal learning also supports personal development, in areas like health and nutrition, social development, physical fitness, and development of hobbies, interests and long-term career goals. Formal instruction prepares students for making the most of their experiences and builds on these experiences. For example, formal study of math provides the tools and approaches needed for analyzing information and solving problems. Formal study of biology enables students to understand, analyze and organize the things they observe in informal observation and field studies. Formal study of history and government gives students a context for understanding the information they gather when working on local history and community service projects. As you think about creating a balance between formal and informal learning, you will think first, of course, about your setting. The approach to learning will be different in an academic classroom, an art class, a web design class, a health or consumer science class, an after-school enrichment program, a summer program, a youth employment program or other setting. Consider the expectations that you, your students, their parents and your school leadership have about what type of activities and what type of learning to expect in different settings. It is important to be respectful of the need for a balance Contextual Learning Guide – Page 5 of 28 between formal instruction and informal learning. Students and parents will be most enthusiastic about informal learning if it is clearly viewed as complementing and not competing with formal instruction. As you browse the projects in the Contextual Learning Portal, you will see many examples of how formal and informal learning are complementary. For example, the hands-on components of a project may be complemented by writing activities, vocabulary lessons, reading, web-based research, lectures about a topic, surveys, data analysis, or other formal learning approaches. Some projects pair formal and informal components based on the same theme, such the informal learning experience of building a garden, paired with formal lessons about food systems, economics, geography, or even topics like gardens in medieval history or literature. Each activity could stand alone, but the pairing of activities provides an interesting connection that students will enjoy. What instructional techniques will you use to support your students in learning? How can you make sure that students are really building skills and competencies while exploring the contextual learning topic? Consider integrating a variety of effective instructional strategies and techniques into your project design. For example: Pre-writing activities Journals Reflective writing Graphic organizers Systems diagrams Mapping Vocabulary bank Reading Web search Storyboarding (for a video or other media project) Writing (for websites, handbooks, brochures or other materials) Use of graphing software Guided or structured note-taking during lectures, guest speakers and workshops Contextual Learning projects typically combine formal and informal learning, with hands-on components complemented by writing, research, background study, analysis and presentation. A thoughtfully-developed mix of instructional techniques is important for supporting all types of learners. Some students thrive in an informal learning setting; enjoying picking up concepts from exposure through informal learning. Other students thrive in a more structured setting, enjoying focused instruction, reading and review. Most students will do well when projects provide a balanced approach, appealing to all styles of learning. Most students will benefit from approaches that nurture creative and critical thinking and build opportunities for reading, writing, research and analysis of information. One of the common elements in Contextual Learning projects is the use of reflective writing. As described in the box on the following page, reflection serves the goals of helping students to consolidate their knowledge and to expand on their ideas and insights. Both goals are important. Students need to have a chance to review what they have learned so that they can “solidify” that knowledge and use it again, whether for tests, quizzes or papers; for future study; for resumes, job interviews or college applications; or for future classroom, community or workplace projects. Students build creative and critical thinking skills, leadership skills and analytical skills by engaging in questions that allow them to explore ideas and generate new insights. Contextual Learning Guide – Page 6 of 28 What assessment techniques will you use? What assessment techniques will help you to assess individual student work as well as evaluate the success of the project overall? Approaches to assessment of student work include: Reflective writing and journal writing; Students creating a portfolio about the project (with photos, essays, spreadsheets, presentation materials, project timelines and notes and other materials); Vocabulary quizzes related to the project; Quizzes about background reading and lecture material; Self-review of participation and outcomes of the project; Peer review of final products; Individual products – such as students individually creating a garden design plan that was graded using a rubric; students creating Excel spreadsheets; students creating tri-fold display boards or PowerPoint presentations summarizing the project. Evaluation of the success of the projects overall can include: Surveys of participants; Pre-program and post-program surveys; Formal or informal feedback from participants; Informal observation; Formal or informal program evaluation tools. Teachers and program leaders should consider different learning styles and learning needs when designing instructional strategies and assessment strategies for contextual learning projects. Some students like the break from routine offered by special projects, while others prefer (and sometimes need) the consistency of more traditional patterns of instruction and assessment. A concern about project-based learning in the past has been that for some students, the assessment and grading of projects, with sometimes-unfamiliar assessment requirements can be frustrating and lead to poor outcomes. Even the most enjoyable project can lead to a sense of frustration if the student feels that the assessment is not consistent with their efforts or that they have not mastered the skills and knowledge that will be evaluated. One advantage of contextual learning is that projects typically produce real products with real audiences, and so the effort put into a project is rewarded with the built-in feedback of project results and audience enjoyment. While not all projects are immediately perfect, students and instructors can see and evaluate effort, lessons learned and skills gained. Assessment can look at not only the quality of the finished product, but also the project management process (student effort, teamwork, reflection on the process) and the skills, background knowledge, vocabulary and concepts learned. Contextual Learning Guide – Page 7 of 28 Discussion: Reflection Questions Reflection writing is used to help students consolidate what they know and to expand on ideas and insights. Questions that “consolidate knowledge” ask students to summarize and describe activities, review vocabulary and concepts, and assess, compare and contrast information they have gathered. Questions that “expand ideas and insights” ask students to offer opinions, brainstorm, predict, analyze, evaluate ideas and explore ideas. These approaches may be applied to pre-writing activities that take place at the beginning of a project and to reflections and journal writing that take place throughout the project. Techniques for helping writing to flow easily include: Write a list… As a writing prompt, ask students to write a list – such as a list of 5 questions, 5 key facts, 5 vocabulary terms or 10 tips. Express your opinion…. Provide questions that allow students to explore a variety of points of view and avoid those where students will feel that they “ought to” answer a certain way. For example, questions like “what can you do to reduce global warming…” or “how can you improve your eating habits” feel like “ought-to questions” and do not allow students very much room to explore their own ideas. Students are likely to be more engaged by questions like “why do people disagree on this issue?” or “in your opinion, what approaches to public policy (or public education) would be most effective in addressing this issue?” or simply “write a dialogue between two people who hold opposing viewpoints.” Imagine a scenario…. Ask students to imagine a particular scenario – an interview, presentation, video project, writing project, etc. – and outline what they would say. One of the strengths of contextual learning is that students actually DO have the opportunity to apply their knowledge in real-life settings, such as making a presentation to a community audience, writing a brochure or developing a video about their topic. They can also “rehearse” for these real-life settings by writing about what they will say in various scenarios or project settings. Empower yourself…. Ask questions that help students think about what they would do and what goals they would set if they could eliminate barriers, or “have a magic wand,” or have abundant resources to address an issue. For example, “Imagine that you had a $5000 grant to address this community issue…. What would you do with this money?” or “Imagine that you were designing a program for elementary school children about this topic. What would you include in the program?” Examples of pre-writing activities: Write ten questions about the topic. Read background information and write an outline of key facts. Read background information and write a list of vocabulary and key terms. Have you worked on projects/activities related to this theme before? If yes, describe what you have done. If no, describe what you expect to see and learn. Examples of reflective writing activities: Did this project confirm any previously-held beliefs or expectations? Did you learn anything that surprised you? What skills did you exercise in this project? Choose a controversial question related to this project and write a dialog between two people debating the topic. Some basic principles: Reflection writing prompts should be respectful of the students, age-appropriate, allow diverse answers, and be consistent with your instructional and assessment goals. Look at the “Browse Techniques and Strategies” and “Browse Resources” sections of the Contextual Learning Portal for more ideas. Contextual Learning Guide – Page 8 of 28 Discussion: Assessment and Evaluation Tools Selection of assessment tools for evaluating student learning and evaluating program success may depend on the context of the project. Some specific student and program assessment tools include: Assessing Student Learning: CVTE Competency Tracking. For Career/Vocational Technical Education (CVTE) programs, student assessment may be managed through the Massachusetts Department of Elementary and Secondary Education’s CVTE Competency Tracking System. Read more about this at http://www.doe.mass.edu/cte. Work-Based Learning. For workplace experience programs and many service learning programs, the Massachusetts Work-Based Learning Plan (WBLP) may be used to assess student learning and skill gain. Read more about this assessment tool at http://www.doe.mass.edu/connect and http://skillspages.com/masswbl. Evaluating Programs: 21st Century Community Learning Centers. For 21st Century Community Learning Centers, program assessment is implemented using the Survey of After- School Youth Outcomes (SAYO) system created in collaboration with the National Institute on Out-of-School Time (NIOST). The Survey of After-School Youth Outcomes (SAYO) is a research based evaluation system that uses brief pre- and post-participation surveys to collect data from school-day teachers, 21st CCLC program staff and youth participants. The SAYO enables the 21st CCLC programs to capture information reflecting changes that are (a) associated with participation in high quality out-of-school time programs and (b) likely to occur over a one-year period. Read more at http://www.doe.mass.edu/21cclc/ta/sayo.html. The SAYO system includes the Assessment of After- School Program Practices (APT) tool, an observational instrument used to assess the extent to which 21st CCLC programs are implementing practices congruent with their desired SAYO outcomes. Read more at: http://www.doe.mass.edu/21cclc/ta/ Community Service Learning Projects. Service Learning Projects may be assessed through the “Assessing Your Service Learning Project” checklist, which is available on the Contextual Learning Portal and on the ESE website. The checklist focuses on meaningful service, youth voice, links to curriculum, reflection, partnerships, diversity, progress monitoring and duration and intensity of projects. At Harwich High School, students complete Senior Discussion: Assessment and Senior Capstone Projects Senior Capstone Projects. Many schools are implementing contextual learning projects as “senior capstone projects” – allowing seniors to select and implement a service learning project, career exploration, arts project or other project as part of their work toward graduation. For these projects, assessment strategies will include a written report, a visual or oral presentation, a project journal or portfolio, and other products. Contextual Learning Guide – Page 9 of 28 Capstone Projects, selecting projects focused on an area of interest. The Herring River salt marsh restoration project was one of the senior capstone projects. Assessment includes observation of student work and final presentations. Participants are observed interacting with other researchers, testing equipment and with study sites. Research activities and findings are presented to the public after the completion of the project. Students may to make public presentations, poster presentations or web-based presentation to share findings. Final presentations include research data sets, photographic data and graphic data. Who is engaged in work related to the theme you want to pursue? What individuals and organizations in your school and community are engaged in work related to the theme you want to pursue? Are there any organizations engaged in current projects that you might support – such as public education, advocacy, communication/media projects or special events? Who in your school and your community can help to provide community connections, background about the topic, access to primary sources, technical assistance and an audience for your work? Are parents or family members potential partners for the project? The template used in the Contextual Learning Portal includes questions about who was on the project team, what resources were used and what technical assistance was used. Viewers can browse the portal to see that projects brought together a wide array of resources, such as environmental groups in the community who guided projects; technical assistance that supported video production, podcasting or web design; local museums and historic sites that provide context for projects; and guest presenters who provided lectures, workshops and other support to student projects. Frontier Regional High School students collaborated as youth curators with the Great Falls Discovery Center in Turners Falls and Memorial Hall Museum to create a new exhibit in a public space on a topic of current interest. Is the theme one that will appeal to students? Is the theme one that will appeal to students? What was the inspiration for the project? Is the project age-appropriate, respectful of diverse views and backgrounds, and open-minded in the approach to social, political or economic issues? The current emphasis on studying contemporary themes stems from both the desire to share new and emerging knowledge and ideas with students and from the idea that students are inspired by engaging in current issues. However, people who work with students and youth programs know that sometimes a thoughtfully and enthusiastically prepared class lesson, workshop or project on an interesting contemporary theme will somehow fall flat when presented to students. Success depends on not only the theme, but also the project design. There are several reasons that students are may or may not be excited by activities based on real-life themes. Is the theme new and fresh to them? Or have they already participated in many similar activities about the same theme? Are students developmentally ready for the topic or is the topic one that they are not ready for? This could be an issue, for example, if younger students are presented with activities about gender equity or other issues that they have not yet encountered; while older students may be very interested in these topics. Is the project bias-free or might students perceive the activity as making unwelcome judgments or assumptions about their lives? This could be an issue if students are presented with anti-violence or anti-gang curriculum that somehow implies that their lives are shadowed with violence and gang activity; or curriculum about the “obesity crisis” and “food deserts” that suggest negative assumptions about the quality of their communities and lifestyles. Does the project feel age-appropriate? Is the presentation of the topic respectful of students’ ages, abilities and interests, allowing them to engage in exploration and gain skills and knowledge? Contextual Learning Guide – Page 10 of 28 In some cases, students may be involved in identifying projects and topics. In schools where community service learning, senior “capstone projects” or other contextual learning projects are part of the school curriculum, teachers may involve students in identifying issues and thinking about possible projects. Schools may present a set of choices for students to select from, such as one school highlighted in the Contextual Learning Portal that presented several possible areas of focus for their senior capstone project initiative. In other cases, community-based or school-based partners will determine the project selection process. Contextual learning projects may develop through the invitation of a community partner to work together on a particular project. Or projects may develop because the school has a commitment to work on nutrition and health topics, anti-bullying programs or other school-community-related topics. Or projects may develop through an opportunity or idea developed by a classroom teacher, guidance counselor or after-school program leader. Projects may focus on contemporary themes or may focus on themes that are not necessarily current or contemporary. Themes may be inspired by local history, by the work of local organizations, or simply by shared interests of teachers, program leaders, students and others. Whatever the origin of the project idea, one of the best ways to encourage student engagement is to make sure that students are given the tools to learn and latitude to explore, discuss, write and reflect about the topic, rather than just a set of "answers" about a topic. These tools can include everything from tips and coaching about research, note-taking skills and writing skills for the project to background knowledge of relevant history, political principles and constitutional law, to information about where and how to find and analyze statistics and information about the topic. Given these tools, along with a structure that allows varying opinions and approaches to the topic, students will feel a sense of mastery to be able to take a topic in whatever direction and to whatever level they want to explore. It is important to provide discussion questions, writing prompts and an open-minded approach that allows students to look at a topic from different angles. Most topics, even those that appear not to have “room for debate” can provide opportunities for research, exploration and discussion of multiple points of view. For example, there is little room for debate that a diet rich in fruits, vegetables and whole grains is healthier than a diet heavy in sugars and fats. However, students can research and debate methods for influencing people to adopt healthier eating (School lunch reforms? Changes in local fast food options? Public education campaigns?); and can debate about the most effective approaches to public service messaging. Does this project help students (and families) connect with people, resources and ideas that they may want to explore beyond the life of the project? Does this project offer connections with others in the school or wider community that help students to develop civic awareness, learn about career and college opportunities, learn about health resources or make other important community connections? Does the project expose students (and perhaps parents and other family members as well) to activities, experiences and skills that they may want to explore beyond the life of the project? The more students are exposed to interesting experiences through school, after-school, workplace and community-based programs, the more experiences they will have to draw from as they are shaping their careers, developing lifelong interests and developing lifelong habits of civic engagement and healthy personal lifestyles. One of the best ways for students to develop college and career awareness, civic awareness, health awareness and other “lifelong” skills is to meet people and to learn about local businesses and Contextual Learning Guide – Page 11 of 28 organizations that are doing interesting projects. Contextual learning projects provide ways for local businesses and community members to connect with local students and to provide ways for students to connect with community projects and potential future career interests. Even the smallest community connections have long-term benefits for students. Students build a sense of belonging to a community and a sense that they community cares for them through their early experiences. Youth are likely to develop a stronger sense of civic participation and a stronger work ethic when they see how others have invested in their communities and how their community supports their growth and learning. Examples include: Field trips to local businesses, organizations, parks and historic sites show students how other invest in the community and contribute to the fabric of the community. Participation in youth programs in the community — sports, arts, technology, recreation — communicate a sense of a caring community to children as they are growing up. Projects might also connect families with community activities, perhaps inspiring a long-term family connection to resources and activities in the community. Community experiences that children have with their families, such as shopping in neighborhood stores, going to local parks and playgrounds and attending local events, help to shape a sense of community. Community connections with police and other public safety personnel through day-to-day interaction, special events, youth/police sports and other events shape a sense of community. Career speakers, career-related field trips, and job shadows help youth begin to see themselves in various professional roles in the community and beyond. Projects may introduce students to local health resources, media resources, community resources that might inspire potential hobbies and personal interests, areas for reading and learning more, and areas for potential further student and/or careers. The “Vision for Career Readiness” highlighted in the following box illustrates ways that classroom, community and workplace experiences, both in school and out-of-school, starting in the earliest grades, can build a foundation for career readiness. Contextual Learning Guide – Page 12 of 28 Discussion: A Vision for Career Readiness Career readiness is created through a continuum of a strong academic foundation plus classroom, community and workplace experiences that build interests, passions, knowledge and skills that youth need to do well in first steps after high school and in long-term career management. Career readiness includes the following foundation and experiences. 1.) Strong academic foundation — having a strong foundation in core subject areas — with skills including literacy and communication skills, critical thinking, mathematical literacy, civic awareness, history and economic literacy, scientific literacy, information skills, the arts, music and languages. 2.) Classroom, community and workplace experiences - with enrichment experiences starting in elementary school, continuing through all stages of education, and including school-day and out-ofschool-time experiences. These experiences build students’ knowledge and skills and help them to develop potential interests and ignite passions. These experiences build four areas of readiness: Applied academic skills – seeing how writing, math, research, information, critical thinking, creative thinking, scientific, design and technology skills are applied in classroom/community/career settings. Having opportunities to “try-out” and demonstrate these skills. Essential career skills — understanding how basic foundation skills and higher order skills — professionalism, teamwork, goal setting, motivation, communication, project management, customer service, leadership, entrepreneurial thinking — are used in classroom/community/career settings. Having opportunities to build and demonstrate these skills. Career awareness and career management skills – understanding how to learn about career options, understanding how job markets evolve and change, knowing what types of careers people have, knowing how people prepare for and navigate various career paths. Understanding how to set goals, navigate transitions, find mentors, seek out information and build a network of support. Building personal resiliency and persistence. Interests and passions – having academic-subject-related and career-related interests and passions — as a starting point for further study, personal exploration and/or career development. Opportunities to enjoy the arts, journalism, science, technology, engineering, design, environmental study, math, media and other interesting areas. Opportunities to organize community events, participate in community service, work on leadership projects and participate in the arts. Opportunities and encouragement to explore books and media on all types of subjects. Opportunities to begin to explore in-depth and to develop skills and knowledge in areas of interest. Reprinted from the Skills Pages Youth Employment Blog January 24, 2012 Contextual Learning Guide – Page 13 of 28 Does this project idea offer enough depth and challenge? Does this project idea offer enough depth and challenge to let students exercise essential skills in areas such as critical thinking, creative thinking, writing, research, data analysis, scientific observation or leadership? A contextual learning project should offer skill-building opportunities, depth and challenge in proportion to the time invested in the project and the learning expectations and goals of the project. One common criticism of project-based learning in recent years has been that projects have lacked depth; that academic connections were too elementary; or that the amount of time spent in hands-on activities was not balanced by complementary learning activities. The best response to this criticism is to provide an honest focus on the goals of each project and the skills exercised. Good schools offer students a rich blend of classroom experiences, field trips, after-school activities, social activities and personal and academic enrichment. The overall mix of experiences supports students in developing academic knowledge and skills, developing personal and social skills, and gaining skills, knowledge and experience that can be applied to future careers, civic involvement and personal life. At Tantasqua Regional Middle School, a Memorial Day Breakfast marked the end of a multidisciplinary project that included reading the novel “Sunrise Over Fallujah” about the current conflict in Iraq, interviewing local veterans, writing poetry, and creating art. In support of this rich blend of experiences, some contextual learning projects will provide in-depth study, while others will provide just a quick glimpse of a particular area of study. Some projects will focus on academic subject areas while others will focus on health awareness, personal and social skills, civic awareness, career awareness and other life-related skills. For example, a one-day field study of a river, wetland or ocean environment may simply expose students to field study and observation skills. Or, for example, a gardening project may solely be designed to teach students about gardening and healthy food. These are legitimate approaches to learning, part of the overall mix of experiences that support student learning. Other projects may have a more classroom-oriented and academic focus, and will engage students in learning vocabulary and studying relevant concepts from science, history or other subjects, as well as collecting observations, analyzing data, studying issues, and working on articles, journals, presentations, maps, charts and graphs or other products related to their work. Projects may seek to provide interdisciplinary connections, bringing together science, math, history, geography, writing, literature, the arts and other subjects, helping students to understand key concepts in the context of several subjects and approaches. Appendix 1 provides examples from the Contextual Learning Portal of projects that build and exercise critical and creative thinking, leadership skills, data analysis skills, health literacy, environmental literacy and other skills. Contextual Learning Guide – Page 14 of 28 Appendix 1: Spotlight on 21st Century Literacies and Project Skills The following pages provide a look at some common areas of focus for contextual learning projects, including “literacies” such as environmental literacy or media literacy and some essential skills such as creative and critical thinking, writing and data analysis. Project examples are provided for each skill area, including classroom, community and workplace experiences. Selected “Student Worksheets” are also included, with reflective questions about some of the skill areas. For more student worksheets and reflective questions, more projects, and additional instructional ideas, visit the Browse Resources section of the Contextual Learning Portal. Environmental Literacy Media Literacy Health Literacy Economic Literacy Civic Literacy Computer Technology Data Analysis Writing Skills Creative and Critical Thinking Leadership Contextual Learning Guide – Page 15 of 28 Environmental Literacy How can community members, business leaders and educational leaders analyze environment issues and decide on personal and public actions? How can students develop environmental literacy skills that prepare them to become leaders and decision makers about environmental issues? Environmental literacy is a blend of skills, including scientific literacy – knowledge of field study methods, experimental methods, biology, engineering, technology, etc. – plus understanding of history, politics and economics. It includes critical thinking skills, reading, research, data analysis, communication and leadership. Contextual Learning Projects. Examples of classroom, after-school program and community-based projects described in the Contextual Learning Portal include a variety of environmental projects: Students design and develop a nature trail in the back of the high school for use by students and community members. Students map and identify local waterways and wetlands including flora and fauna. Students will determine drinking water source(s) for the community and examine water use and costs as well as the delivery system. Fourth grade classes serve as stewards of the wetlands including a vernal pool behind their school. Students design and plan a community garden. Students determine the electricity usage of the entire school building and practice the reduction of usage. In a sixth grade leadership club, students complete a project that attempts to create an environmentally aware school. There are a variety of components involved in the project including recycling, energy conservation, and school-wide education. Grade 8 students videotape and create a voice-over for grade 6 and 7 environmental projects in order to capture the steps of the scientific process as they happen. Students research and observe bird behavior on and around school grounds. Students conduct an interdisciplinary study about veganism. Students work toward a holistic understanding of the dynamics of salt marsh restoration by studying planning documents, interacting with scientists and conducting various field studies to determine the impact of tidal restriction of a salt marsh ecosystem. Workplace Experiences. Examples of student internship and summer jobs focused on environmental topics include: An intern works on research and education projects related to coastal management for a local environmental nonprofit organization. An intern works at a fish hatchery, with tasks including monitoring fish and collecting and recording data. A group of interns works on energy efficiency projects, including learning skills in weatherization and solar hot water system installation. A group of interns works as auditors for a weatherization project, including assessing needs, preparing cost estimates and monitoring completion of weatherization projects. An intern works with a nonprofit organization that helps local growers to achieve and sustain economic success through marketing and technical assistance. Interns work in urban agriculture and urban gardening, including helping to start and maintain community gardens. Interns work on local farms, including varied projects in energy management, animal care, marketing and general farm work. An intern works with a local elementary school’s environmental education program, including helping to develop educational activities and working on greenhouse, hydroponics, composting and recycling projects. A group of interns develops educational publications for the local community on how community members can promote environmental sustainability. A group of interns works as tour guides and stewards for a state park. Contextual Learning Guide – Page 16 of 28 Media Literacy How can an organization gain visibility through effective use of media? How can an organization create an effective public education campaign using media? What are the characteristics of a high-quality website, video, newsletter, e-newsletter, or other media communication? How can I organize and synthesize information to be presented via various media? What are the technical steps involved in creating websites, videos, booklets, brochures, e-newsletters, podcasts and other media? Communication skills, information skills, critical thinking and creative, artistic and technical skills come together when students use electronic, print and other media in their classroom, community and workplace projects. Through exposure to a variety of projects, youth gain skills as thoughtful and effective producers, consumers and planners of a variety of media. Contextual Learning Projects: Projects in the Contextual Learning Portal shows a variety of uses of media: Elementary school students research and produce a booklet about emergency preparedness, covering how to take care of people and pets during power loss; High school students research a local proposal to restore flood chutes on the Hoosic River and produce a documentary about the issue; After a technology class about cyber-bullying, students conducted an online survey about bullying and used Excel and PowerPoint to present the results to the school community; Students research and analyze media coverage of a presidential election; Grade 8 students produce a video about the scientific process based on a project done by grade 6 and 7 students; Students create a video as part of an anti-bullying project; Elementary school students write, edit and print a school newspaper; Students use media and primary and secondary documents to research the life of a local artist, while learning about general local history and arts; students work with local artists to produce works for an art show. Workplace Experiences: Examples of youth working with media as part of jobs and internships include: Writing press releases; Writing for newsletters and e-newsletters; Researching topics for newsletters and e-newsletters; Working on scripts for television, radio and in-store voice-over promotions for a supermarket; Posting news and announcements to local cable TV; Posting updates to social media; Setting up daily podcasts for school announcements; Creating or updating a website for an organization or project; Producing a promotional video; Researching media coverage for a media book for an organization; Participating in the development of social media strategies. Contextual Learning Guide – Page 17 of 28 Health Literacy In today’s economy, many businesses, organizations and career paths are focused on ways of promoting and preserving personal and community health. From renewed attention on healthy eating to programs for exercise and relaxation to holistic approaches to healthcare and prevention, people are more interested then ever in ways of promoting health. “Health literacy” is an important skill for youth — not only because being health-savvy is important personally, but also because knowledge of health issues can be valuable for career success and career growth. All kinds of organizations — grocery stores, fitness centers, youth sports programs, food banks, community gardening programs, schools and healthcare organizations — value employees who can guide customers and develop marketing and educational materials to promote health and wellness. Contextual Learning Projects. Students explore health literacy through a variety of classroom and community projects as described in the Contextual Learning Portal. For example: Elementary school students organized an Elementary School Health Fair at Union 61, a school serving Brimfield, Brookfield, Holland, Sturbridge and Wales. As part of this project, students selected topics, invited presenters, created exhibits, wrote press releases and developed publicity, managed the event and evaluated the success of the event. Students from Whitman-Hanson Regional School conducted a project about hunger in their community. Students needed to do initial research on healthy eating recommendations, WIC and food stamp information, poverty income guidelines, as well as the cost of food items based on local supermarket circulars. Students participated in a panel symposium in which they taught each other what they had learned through their in-class study, and later heard from experts on the topic of local hunger. They were able to ask questions of the panel and gain a greater understanding of hunger facts within their communities. Students from several schools have organized anti-bullying projects, creating healthier environments for their fellow students. Students from several schools and after-school programs have participated in exercise, nutrition, cooking, community gardening and other health-related programs. Workplace Experiences. Examples of youth gaining experience in health literacy issues include: Understanding exercise and movement as applied in physical therapy clinics and fitness centers; Promoting good health through leadership in youth sports programs; Helping to plan and prepare nutritious meals in a culinary arts program, restaurant, youth program or nursing home; Working on public education and peer leadership campaigns in programs related to health and wellness; Working on a nutrition newsletter, articles and events for a supermarket chain; Working with the school nurse to promote health through a school-wide newsletter and school web page; Maintaining a file of health information resources for the school nurse’s office; Working in medical research projects; Conducting surveys related to health and wellness issues. Working in internships in healthcare, pharmacy, dental care and other settings. Contextual Learning Guide – Page 18 of 28 Economic Literacy Economic literacy comes from an understanding of how markets work, how economic trends shape job opportunities, how businesses succeed and grow, how goods and services are produced and exchanged, and how money flows through the economy. “Economic literacy” refers to general knowledge about economic markets from the perspective of workers, consumers, savers, investors, entrepreneurs, community volunteers and active citizens. Students build economic literacy through experiences that expose them to the type of analytical thinking used in economic analysis and to the general knowledge that underlies economic literacy. Experiences can include: Looking at history through the lens of economic and social change; Studying geography, government and civic awareness; Learning concepts and vocabulary that underlie economic literacy, including competition, markets, income, interest rates and entrepreneurship. Learning about the different sectors and institutions that interplay in the economy — businesses, consumers, government, financial institutions, labor unions and nonprofit organizations; Learning about how the role of government in the economy has evolved over time, as well as understanding different perspectives about the role of government in the economy; Having a variety of experiences in finding, analyzing, presenting and talking about data; Drawing flowcharts or other models to learn how to apply analytical, “cause-and-effect” thinking to economic issues; Participating in in-depth classes, workshops and events about topics of immediate interest – particularly jobs and careers, entrepreneurship and personal financial literacy. Examples of experiences that build economic literacy skills include: Working with a nonprofit organization that helps local growers to achieve and sustain economic success through marketing and technical assistance. Working with a local museum on projects related to local economic history. Writing business plans and starting small businesses through entrepreneurship programs. As a marketing intern, learning marketing skills such as identifying the target market and creating a marketing profile. As an intern in a restaurant, working with the restaurant manager to prepare marketing materials and to survey customers about food and dining experience. As a small business intern, learning to understand all aspects of a small business, including assisting customers, placing orders, handling all transactions and sales, taking inventory, pricing, and learning the financial cycle of a retail store. Contextual Learning Guide – Page 19 of 28 Civic Literacy Civic awareness refers to the foundation that makes people active participants in the fabric of their community and beyond. What makes a person decide to participate in elections, participate in community planning and decision-making, invest in the community, volunteer in the community and feel connected to the community? One of the essential positive developmental steps for youth is establishing strong connections with their communities and the wider world. Youth connect with their communities in many roles – student, neighborhood resident, sports participant, arts participant, volunteer, worker/entrepreneur, voter or soon-to-be voter, and perhaps as participant in town meetings, neighborhood groups and other community forums. A combination of formal and informal learning supports this growth. Formal learning supplies the concepts that underlie civic participation: understanding of democracy, voting and elections, the structure of local, state and federal government, the US Constitution, the history of democracy and civic participation. Informal learning supplies the experiences that reinforce a desire to connect with the community and contribute to the community. Early experiences like elementary school field trips to local businesses, organizations, parks and historic sites show students how others invest in the community and contribute to the fabric of the community. Students can gain civic awareness and gain experience in civic engagement through contextual learning projects and work experiences that immerse them in projects and issues in their communities. Examples include: Organizing a school-wide interdisciplinary Memorial Day celebration, which includes extensive reading, writing, artwork, interviewing local veterans and hosting a veterans breakfast; Studying issues affecting veterans and participating in service projects in support of veterans organizations; Working on energy conservation and weatherization projects; Working with a local advocacy group to restore a dam on a local river; Helping to promote farmers markets; Organizing food drives and clothing drives; Creating public information campaigns on themes of community health, anti-bullying or other topics; Studying local and national elections and sharing information with the school community; Conducting surveys about local issues; Working in internships with elected officials, city and town departments, advocacy organizations and other organizations involved in civic and community action. Contextual Learning Guide – Page 20 of 28 Computer Technology What skills do students use in projects in computer technology fields? Computer technology skills can be broadly defined as including three areas of strength: (A) Computer Literacy: the ability to learn, communicate effectively, collaborate, and problem solve about computer-technology-related tasks and projects; and (B) Using Computer Applications: the ability to use technology to support your work, such as using technology in an engineering lab, design studio or research program; using technology to develop print and online materials; using technology to organize and present information; using technology to create and maintain databases; and/or (C) Providing Technical Support: the ability to support others in the use of technology, such as setting up computer workstations or AV equipment for people, teaching computer skills, troubleshooting technology-related issues, and maintaining and repairing computers and related equipment. Contextual Learning Projects. Examples of contextual learning projects using technology include: Web design; Video production and editing; Creating a student newspaper; Creating spreadsheets, presentations and other materials. Workplace Experiences. Examples of job and internship placements using technology include: Help Desk / Tech Support: Students providing customer support, computer repair, troubleshooting, software installations, inventory and cataloging, and other technical support. Audio-Visual Support: Setting up audio-visual equipment, troubleshooting, repairing and supporting school or other organization staff in their media needs. Web Design and Graphic Design: Students providing web design, web media (such as podcasts), website maintenance and graphic design work. Database Management: Using databases to collect, organize and manage information. Software Development Internships: Student interns working on a team with software developers on a software project. Student Worksheet How do you like to learn? How do you like to learn something new, such as cooking something you have never cooked before or learning a new computer skill? Read print materials - recipes, instruction books, etc. Read online - websites, technical forums, etc. Watch a video Watch another person Talk on the phone to someone who knows how to do it Email someone who knows how to do it Experiment - just try it out Figure it out by thinking about how similar things work (similar recipes, similar computer software, etc.) Contextual Learning Guide – Page 21 of 28 5 = Yes I like this approach 4= Somewhat like this 3 = Inbetween 2 = Not very much [5] [5] [5] [5] [5] [5] [5] [5] [4] [4] [4] [4] [4] [4] [4] [4] [3] [3] [3] [3] [3] [3] [3] [3] [2] [2] [2] [2] [2] [2] [2] [2] 1 = No I don't like this approach [1] [1] [1] [1] [1] [1] [1] [1] Data Analysis One of the best ways to become familiar with a set of data is to work actively with the data, drawing graphs, creating charts, sorting the data, calculating percentages or other hands-on analysis. As you work with the data, you notice interesting points, patterns and relationships that you might not notice if you just glanced at the information while reading. Contextual learning projects build data analysis skills through: Collecting and analyzing survey results; Analyzing data about public issues; Analyzing and graphing data from science field studies and observations; Analyzing labor market data and other career-related information; Analyzing data for business plans and marketing plans; Other applications Student Worksheet: Data Analysis Insights As you work with any data sets, consider the following questions: Do you get any new insights (or surprises) by looking at the data? Does this data support any views that you already had? What patterns do you see in the data? What exceptions do you see to these patterns? Do you notice any interesting relationships between sets of data? Are there any “cause-and-effect” relationships implied by the data? Do you notice any trends over time? Look for: Highest values – which occupations/countries/groups/etc. have the highest values? Lowest values – which occupations/countries/groups/etc. have the lowest values? Distribution – is the data distributed across a broad range of numbers or clustered around a small range of numbers? Skewness – are most of the values high or low or evenly distributed across the range of numbers? Relationships between two or more data series. – Is there any correlation between two series of numbers? Ask: What does this data represent? Are there any vocabulary/terms that I need to look up? Can I explain the data to another person? Decide: What is the best way to present this data? Should it be presented in a table or in a graph? What type of graph is best? What should the title of the graph or table be? What are some key points that I could highlight in text accompanying my graph or table? Contextual Learning Guide – Page 22 of 28 Writing Skills Writing in workplace and community settings draws on the same basic writing skills used in classroom settings but with a particular focus on working collaboratively, using particular formats and writing for particular audiences. Collaboration: Working collaboratively to produce a written product, with project team members involved in planning, outlining, drafting, revising, editing, fact checking, proofreading and formatting the product; Format: Writing for a particular format, with writing styles that vary for the setting, such as websites, brochures, press releases, news articles or surveys. Audience: Focusing on the audience, with an emphasis on providing clear information or persuasive arguments, with information presented concisely and attractively. Contextual Learning Projects. Contextual learning projects provide an environment for students to experience the variety of writing and communication skills used in workplace and community settings. Through contextual learning projects, students might: Write text for a website Design a brochure Write a press release Write a news article Write survey questions for a community survey Create a story board for a video Write text for museum exhibit signs and labels Write a handbook or manual Write opinion pieces on an issue facing the community for a newspaper, website or other media. Workplace Experiences. Examples of writing in workplace experiences include working on: manuals technical documentation press releases grant proposals newspaper stories obituaries sports reports test and discussion question banks for classroom teachers story banks for newspapers websites form letters letters emails daily logs patient charts meeting notes helping others with their writing working as teaching assistants supporting younger children in story writing working as music production interns supporting musicians in music writing Contextual Learning Guide – Page 23 of 28 Creative and Critical Thinking Contextual learning experiences allow youth to see how creative and critical thinking are balanced and used in a variety of real-life situations. Creative thinking expands possibilities — creativity is used to generate new ideas, “break out of the box” and think of new ways to do things. New ideas may be small or large, radically different or just a slightly fresh approach. Creativity involves giving yourself time for thinking, brainstorming and generating idea, using creativity-building approaches like brainstorming, word-association, mind-mapping, free-flow diagrams, creative doodling or other approaches to stimulate your creative thinking, and allowing yourself to explore new ideas without worrying about being wrong or off-track. Critical thinking shapes effective action — critical thinking is used to assess new and existing ideas and strategies, gather and weigh evidence, and sharpen insights into your goals and work. Like creativity, critical thinking can be described as “thinking outside the box” — looking at information in several different ways in order to draw good conclusions. Critical thinking may be defined as making decisions based on objective information, decision making criteria, logical thinking and common sense. To be an effective critical thinker you must understand the goals of your project, understand how to use available information, and then take time to systematically analyze available information and apply decision-making criteria. Creative thinking and critical thinking can be applied to smaller everyday decision making and to bigger decisions about projects, policies, business ideas and business plans. Some examples of creative and critical thinking in various project areas: Identifying and assessing variations on a recipe in a culinary arts program; Designing and leading a literacy program for younger children; Designing and leading craft activities for children, elderly nursing home residents or other audiences; Developing signs, exhibits and displays for a museum or a zoo; Developing public education campaigns about community issues; Working on business plans and marketing strategies in entrepreneurship projects; Developing and analyzing surveys about school-related issues; Learning about bullying and school climate issues and recommending strategies for improvement. Student Worksheet: Creativity Reflection Questions What are the ingredients that generally help you be creative? In what ways did this experience help you to work creatively? Do you know how to use creativity-building approaches like brainstorming, word-association, mind-mapping, free-flow diagrams, creative doodling or other approaches to stimulate creative thinking? Describe the approaches you use. Can you identify any creative contributions you have made in this project? (These can be small, “everyday” contributions with a new, fresh approach) Do you think that creative thinking is important in ALL jobs or just in artistic and creative sector jobs? Explain. Contextual Learning Guide – Page 24 of 28 Leadership What are your strengths as a leader? Your leadership style may change from one situation to another, depending on the project you are working on and on the needs and relative strengths of other team members. Examples of use of leadership in contextual learning projects and work experiences include: Playing a leadership role in programs for younger children; Leading sports and other activities in summer and after-school programs; Planning and carrying out community service projects; Working as mentors and leaders in peer leadership programs; Leading and instructing others through formal supervisory and mentoring roles; Assuming an informal leadership role among peers; Participating in leadership development workshops. Many young people have grown up with the concept of collaborative, participatory group leadership roles. Rather than thinking of a group leader as being a “take-charge” person and having strong persuasive skills, popular views of leadership include good listening as well as good speaking skills, being a good role model, a skilled facilitator of group meetings, and being a helpful and productive team member. Youth tend to be comfortable with the idea that “leadership skills” are part of a broad set of skills that includes project management, interacting with others, knowledge and awareness of relevant issues, as well as formal group leadership skills. The “Leadership Strengths” reflection below provides an exercise for looking at leadership strengths. Student Worksheet Leadership Strengths Your Leadership Strengths 5 = very strong 4 3= Inbetween 2 1 = not currently strong Knowledgeable – always has good information [5] [4] [3] [2] [1] Uses talents to contribute to a group project (such as being a good writer or artist or good at doing research) [5] [4] [3] [2] [1] Friendly and fun – keeps people enjoying the group work [5] [4] [3] [2] [1] Hard-working [5] [4] [3] [2] [1] Nurturing – pays attention to other group members and what they need [5] [4] [3] [2] [1] Good listener [5] [4] [3] [2] [1] Good at persuading others [5] [4] [3] [2] [1] Helps a group to set goals and set timelines [5] [4] [3] [2] [1] Motivates others to work hard [5] [4] [3] [2] [1] Good at explaining things [5] [4] [3] [2] [1] Helps others to make decisions [5] [4] [3] [2] [1] Good role model to other group members [5] [4] [3] [2] [1] What are your current strengths as a leader? Rate on a scale of 5 (very strong) to 1 (not currently strong) Contextual Learning Guide – Page 25 of 28 Appendix 2: The Contextual Learning Project Template This template is used in the Contextual Learning Portal in the “Submit Project” section. Website: http://resources21.org/cl Contextual Learning Project Template 1 – BASICS Use this section of the template to identify basic information about the project. Include any information that will be helpful to others who want to implement this project or a similar project, including resources and team members needed and modifications or extensions made to the project. You may alter the headings if you wish. Project Title Theme Submitted By Organization Brief Description Materials / Resources Team members Pre-requisite knowledge Technical support needed Any modifications or extensions for particular student populations? What subject areas does this project focus on (check all that apply)? [ ] ELA [ ] Mathematics [ ] Science [ ] History [ ] World Languages [ ] Arts [ ] Technology [ ] Physical Education [ ] Career/Vocational/Technical [ ] Service Learning [ ] Other If funded by an ESE Grant (such as Academic Support or 21st Century Community Learning Centers): What Fund Code? What Time Period? [ ] Summer [ ] School Year What Grade Level(s)? Contextual Learning Guide – Page 26 of 28 2 - KEY QUESTIONS Contextual Learning projects are based on authentic KEY QUESTIONS that are meaningful to students and that mirror questions addressed by adults in the workplace or community. Use this section of the template to identify the key question that the project will address and describe the context of the project. Key Questions Connections: How or why was this topic identified? Why is it meaningful? Background Research: What resources were used to find background information for this project? Outcomes: What was the outcome? How was it shared or applied in the community? 3 - FRAMEWORKS / SKILLS Use this section of the template to identify the curriculum frameworks and skills that the project will address. You may mix-and-match among the different sets of project frameworks, including the Massachusetts Curriculum Frameworks, 21st Century Skills, and Work-Based Learning Skills. See the Browse Frameworks page for more information and examples. [See website for checklist of frameworks and skills] 4 - UNITS / ACTIVITIES Use this section of the template to describe the sequence of units or activities in this project. Use the first column to identify the unit (i.e., "Day 1" or "Unit 1") along with the time required. Use the second column to describe the activities. Use the third column for additional comments, including needed resources, ideas for modifications/extensions, or other comments. Name of Unit With Time Required Activities / Description Details: Contextual Learning Guide – Page 27 of 28 Materials/Resources Modifications, Extensions 5 - INSTRUCTIONAL TECHNIQUES Use this section of the template to identify instructional techniques and strategies Techniques / Strategies Description 6 - ASSESSMENT TECHNIQUES Use this section of the template to identify assessment strategies. Techniques / Strategies Description 7 - Publish and Tag [See website for instructions for publishing and tagging the project.] How Can I Use the Contextual Learning Portal? The project template can help you organize your ideas and “go deeper” in creating high quality learning experiences. Use the sign-up screen to sign up for a username. A password will be emailed to you instantly. Once you have signed in, you can go to the project template to share information about your project. Any teacher, counselor or youth program staff is welcome to sign up for a username. You are welcome to share projects that are in the planning stage as well as projects that you have completed. Once you have started entering project information, you can save your information and come back to it another day. The portal is set up so that you are always able to add information, photos or resources to your project, such as when you share your initial project plan and come back to add photos of student work later. When you are ready to share your work, go to the “Ready to Publish” tab to designate your project as ready to publish. Within 24 hours, your project will be available for others to browse. Contextual Learning Guide – Page 28 of 28