Editing (Wednesday)

advertisement

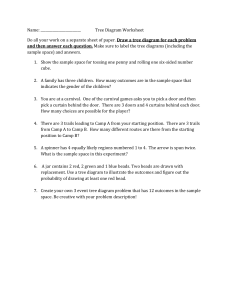

FULL EDITING MODULE: WEDNESDAY AFTERNOON Task brief The text below is taken from an academic book about Holocaust remembrance in Poland after the Second World War. This translation was done as a collaborative translation exercise by a group of MA students whose native language is Polish. The book is to be published in early 2014 by Peter Lang in Switzerland. ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Places of remembrance, places of oblivion Starting in the 1990s, the term ‘places of remembrance’1 became very popular in Poland. It has been used especially in the context of World War II, to define the areas of the former Nazi concentration and death camps. Many of those areas, however, have never received a dignified commemoration, whilst some for many years remained, or still remain, entirely abandoned. Therefore, they would deserve more to be called the ‘places of non-remembrance’ or ‘places of oblivion’. Whether a particular site was commemorated or not, depended on a number of different historical, political and practical factors. This could have been determined not only by the type of camp and the number of victims, but also by the nationality of the victims. The level of activity of the resistance movement supporting an appropriate political orientation within the camp also may have contributed to the ennoblement of a particular camp, as it happened in the case of Auschwitz. Moreover, the geographical location and the accessibility of the site, as well as condition of the camp buildings were not without significance. Even after 1945, some of the former Nazi concentration camps were still used as places of isolation for prisoners of war, German civilians or native political opponents, which made the commemoration impossible or at least delayed. This has been the case with Świętochłowice, Potulice and Jaworzno2. Also, the fate of the former camp 1 This term may be used in its wider meaning as places and other historical symbols that make up the identity of a given community (lieux de mémoire, Erinnerungsorte, Gedächtnisorte). This is the way the term is understood by Pierre Nora (Les lieux de mémoire; Zwischen Geschichte und Gedächtnis, pp. 32-42). For a discussion of Nora’s ideas, see also Szpociński (Miejsca pamięci) and Etienne François and Hagen Schulze (Introduction, in: Deutsche Erinnerungsorte, published by E. François and H. Schulze, Vol. 1, München 2001, pp. 17-18). In its narrower meaning the term denotes historical places commemorated in the form of plaques, monuments, cemeteries or museums (German: Gedenkstätten). In this sense the term is applied in Germany, Austria and, more recently, in Poland, to define museums and monuments that have arisen on the sites of former concentration and death camps (see, for instance: Tomasz Kranz, Edukacja historyczna w miejscach pamięci, Lublin 2000, pp. 37-57, 129-130). In Poland, until the 1990s, the sites of former concentration camps and other places connected with the Second World War were rather called “martyrology sites” or “monuments of struggle and martyrdom”. 2 Świętochłowice-Zgoda: a penal camp, and then a labour camp that operated between February and November 1945 on the site of a former branch of the Nazi concentration camp in Auschwitz. The inmates of the camp were German prisoners of war, members of the NSDAP and SS, volksdeutsche, reichsdeutsche, and Polish political prisoners. areas was considerably influenced by the number of survivors, as well as the way their sociopolitical status and level of organisation allowed them to lobby for commemorating those places. All of these matters will be discussed in the current chapter. Majdanek or Auschwitz – rivalry for the supremacy On the night of 22 July 1944, the Red Army advanced on Lublin, forcing the last SS military units to leave Majdanek. This was the first concentration camp liberated by the coalition army. Soviet military authorities created an extraordinary commission of investigation almost immediately. In mid-August, Polish representatives were co-opted onto this comission. Andrzej Witos, Vice-Chairman of the Polish Committee of National Liberation (Polski Komitet Wyzwolenia Narodowego, PKWN), became the head of The Polish-Soviet Extraordinary Commission for Investigating the Crimes Committed by the Germans in the Majdanek Extermination Camp in Lublin, whereas his deputy was appointed by the Soviet authorities. The members of the commission presented the idea of creating a museum of martyrdom on Majdanek grounds. When giving the Soviet press an interview, Witos announced that the camp would be preserved, serving ‘as a museum to commemorate human suffering’, and would become ‘visible evidence of the crimes committed by the Germans’ against Poles, Soviet prisoners of war, Jews and those of other nationalities, who were imprisoned in the camp. In October, PKWN decided to form a special bureau that would be in charge of the organisational aspects of the museum in Majdanek concentration camp. None of the first four Chairmen of the aforementioned institution (they were changing fairly often), had been a prisoner of the concentration camp. The first draft of the decree for the formation of the State Museum at Majdanek (Państwowe Muzeum na Majdanku, PMM) was created in May 1945; however, it was turned down by the State National Council (Krajowa Rada Narodowa, KRN). Despite the pleas made by the management of the Museum, its legal status remained unsettled until July 1947. Meanwhile, despite the fact that the Polish Army and Red Army units were still stationed in the camp’s territory, organisation and regulatory works began as early as the autumn of 1944. In a report from November of that year for the Polish Committee of National Liberation, the first director of the Museum, Antoni Ferski, proposed that the Museum illustrates “The whole life of Potulice: a labour camp that operated in the years 1945-1950, created on the site of the former German labour camp. After the war, the people held in the Potulice camp were prisoners of war, volksdeutsche, reichsdeutsche, as well as Poles. Jaworzno: a labour camp that operated in the years 1945-1949/50 on the site of a former branch of the concentration camp in Auschwitz. Incarcerated in Jaworzno were former prisoners of war, reichsdeutsche, volksdeutsche, as well as Poles and Ukrainians (Kopka, Obozy pracy w Polsce 1944-1950, pp. 126-129, 150-152, 159-160). the camp and the torments of the victims, the ordeal they experienced from the moment they entered the camp through all the agonies – ‘experiments,’ ‘exercises,’ ‘work,’ ‘baths,’ punishment and, finally, gassing and the cremation of prisoners in the chambers”. As the Museum only received very modest government grants, the board of directors made every effort to raise additional funding – from publishing brochures and posters, to organising propagandistic fund-raising events. The first such event organised by the Museum’s board was the “Week of Majdanek”, which took place in September 1945. Despite a chronic lack of money, building materials and a means of transport, as well as looting and ongoing disputes with the army stationed at the camp site, the Museum’s permanent exhibition, located in one of the camp barracks, was officially opened as part of the commemoration. Initially, it seemed that Majdanek would become the central place of remembrance in postwar Poland. In order to make the world aware of the enormity of German massacre, as Antoni Ferski wrote in the memorial drawn up at the beginning of January 1945, it had been decided to gather all pieces of evidence at one point. “This central place of remembrance is the State Museum in Majdanek. It is a ‘bloodstain’ on the map of Europe, which will be telling the whole world about the agony of nations, and in particular about the martyrdom of the Polish nation,” wrote Ferski. Majdanek was, however, quickly overshadowed by the Auschwitz-Birkenau camp. This was definitely because of the history of these two places. According to the latest research, about 1.1 million people were murdered in Auschwitz, although past research suggested that there were between four and six million victims. About 400,000 people were registered in the camp in total. However, even according to newer, much lower estimates, it was still the largest Nazi concentration and extermination camp in occupied Europe, both in terms of the number of prisoners and people murdered. Another factor that also had a significant impact on the history of the Auschwitz Museum was that, although more than 90% of the camp victims were Jewish, around 70 to 75,000 Poles were also killed there. This figure was significantly overestimated during the 1940s, and in later years. But even according to the latest calculations it was still, relatively speaking, the largest place of not only Jewish but also Polish martyrdom besides Warsaw. Another crucial factor in the post-war future of Auschwitz was its international character. Apart from the Jews from Poland and other European countries, and Poles, the victims were people of many other nationalities, including Romani, Russians, Belarusians, as well as Germans, Austrians, Czechs, and French. It was also one of the very few Nazi concentration camps, in which an organised and partly transnational resistance movement genuinely existed. Leftist and communist activists played a critical role in this movement, which made Auschwitz a convenient propaganda tool for the new authorities. The fact that Auschwitz grew into the central symbol of national martyrdom in Poland, however, also had more prosaic reasons. Firstly, a relatively big number of people survived the camp, including Polish political prisoners. Secondly, the dominant position in this community was assumed by left-wing activists, including the later Prime Minister, Józef Cyrankiewicz, the President of Kraków, deputy to the National Homeland Council (KRN), and first director of the Bureau of the Central Commission for the Investigation of German Crimes in Poland (GKBZNwP), Alfred Fiderkiewicz, and the head of the Department for Museums and Monuments of Polish Martyrdom at the Ministry of Art and Culture (MKiS), Ludwik Rajewski. Auschwitz inmates also managed to get many of the top posts in the Polish Association of Former Political Prisoners (PZbWP). They consitituted a lobby that very actively tried to have the camp commemorated. In autumn 1945, after the Soviet armies vacated Auschwitz, former Polish inmates sent a memo to Bolesław Bierut asking him to take over the site of the former camp. “The soil of Auschwitz, stained with blood and mixed with the ashes of martyrs – they wrote – calls for the care of state and society. For eternity this soil must remain the property of the entire nation and be commemorated with dignity”. The signatories of the letter declared their readiness to take care of Auschwitz Birkenau themselves. All they wanted from the president was financial support and a guarantee of permanent military protection over the site. In December 1945, at a plenary session of the KRN, Alfred Fiderkiewicz submitted a proposal to turn Auschwitz-Birkenau into “a place for the commemoration of Polish and international martyrdom”. Just two months later, the Presidium of the Council of Ministers decided, in accordance with the former inmates’ wishes, to transfer the site to the Ministry of Art and Culture (MKiS). The PZbWP became intensively engaged in the commemoration of Auschwitz-Birkenau. At first, former prisoners hoped that the authorities would give the managmenet of the site to the Association. And indeed, in one of the first versions of the law on the establishment of the State Museum in Auschwitz of 1946, it was assumed that the administration of the entire complex would be handed to the PZbWP. Even before the legislative work started, former prisoners already set about organising the Museum. In March 1946, MKiS transferred supervision over the Auschwitz-Birkenau site to the Department for Museums and Monuments of Polish Martyrdom; the director Ludwik Rajewski immediately began to assemble Museum staff. Starting with the director and ending with the guards, the staff was almost exclusively composed of former Auschwitz inmates. All employees were approved by the PZbWP’s Executive Board. Already in the summer of that year on the site of the mother camp, a modest exhibition was opened in a cellar of one of the camp blocks. On 14th June 1947, on the the 7th anniversary of the first transport of Polish political prisoners to Auschwitz, the Museum officially opened. The ceremony was given the highest rank. Speeches were made by the Prime Minister and chairman of the PZbWP Executive Board, Józef Cyrankiewicz, the secretary-general of the Fédération Internationale des Anciens Prisonniers Politiques (FIAPP), Zygmunt Balicki, the Art and Culture Minister, Stefan Dybowski, and, representing the Central Committee of Jews in Poland (CKŻP), the Sejm deputy, Józef Sack. Also present were representatives of the CKŻP, of the Joint Distribution Committee, and the consuls of Czechoslovakia, France and Great Britain. After the speeches and religious ceremonies, the exhibition officially opened. Then there followed a solemn procession to the site of Birkenau, where wreaths were placed by the ruins of the crematorium and Rota (Oath), an early 20th-century patriotic song, was sung. “This Museum – said Cyrankiewicz in his speech – shall not only be a warning and eternal proof of German atrocity, but shall also speak the truth about humanity and its struggle for freedom; it shall heighten vigilance so that genocidal forces never again bring destruction to nations”.