Précis - International Network for Engineering Studies (INES)

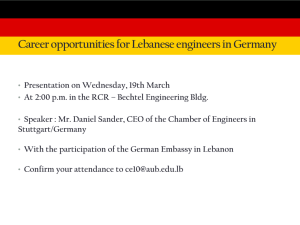

advertisement

“Developing Technologies of Development Technology: Framing US Engineering Projects as ‘Technical’ in Honduras and Nicaragua in the Context of US Engineering Education" Park Doing Cornell University INES Lisbon 2008 This paper follows two engineering projects pursued by U.S. Engineering professors and students in collaboration with the national organization, Engineers for a Sustainable World and Cornell University. The first project is a gravity fed water filtration system in Honduras and the second project is an attempt to promote solar oven use in Nicaragua. The paper brings out how the various groups involved in the projects, including the communities for which the projects are designed, promote the projects as ‘technical’ and requiring of technological expertise. Accounts of the technologies as technological agents of change, requiring attendant expertise, are seen as performances aimed at the variety of audiences of interest to the various groups. The first project is to build and maintain a gravity-fed water cleaning system for a rural community in Honduras. The project is worked on by group of Cornell University students and professors that are affiliated with the student run U.S. organization, Engineers for a Sustainable World, in conjunction with different U.S. based and Honduran based NGOs. The problem as described to the students working on the project, and in press coverage about the project promoted by the university, is that there are communities in Honduras which have chlorinating systems for their water supply, but no systems for removing dirt and other particles from that supply, which hampers the effect of the chlorinating systems in place. A gravity fed series of concrete tank sections that would take dirt out of the water upstream of the chlorination system is seen as cheap, sustainable, and ethical intervention. For the first such plant, which would serve about one hundred and twenty families, the students, the professors, and a Honduran contractor worked for about three years, during which time students, professors, and an agency representative from the United States all visited the site on several occasions. In reports about the project by the U.S. groups, and in portrayals of the project by Honduran groups, the ‘technicality’ of the project was promoted. The university group can be seen as aiming its accounts to the Engineering College in which it is situated. For this group of students and professors, it was important to be seen as a technical project. The Engineers for a Sustainable World group within the college felt and faced pressure that the courses through which the project could be worked on by students were not seen as ‘soft’ courses devoid of mathematics and rigor. As a result, portrayals of the project emphasized an adjustable aluminum sulfate feed system that would adjust the settling capability of the water system depending on the turbidity level at any particular time. That the system was technically sophisticated in this regard was an important point of emphasis for the U.S. engineers, given their audience in the engineering college at large. That the project was technologically advanced was also promoted by the Honduran NGO involved and by the Honduran operator of the plant itself. Speaking at a community meeting regarding the plant, the head of the Honduran NGO lavished praise on the U.S. engineers for bringing their technical expertise to the people of the community and made it clear that such a project was something they could not do on their own. Why would the NGO leader promote the technical expertise of the U.S. engineers and the sophistication of the water system as a contrast with the abilities of the people of his own country? For this person, I learned that the primary audience for him was potential Honduran voters. He hoped to attain national office and being seen as a person who brought something valuable ‘to the people’ was important in that regard. After the system was put in place, portrayals of it by the Honduran operator of the system also promoted its technical sophistication and focused on the alum feed system. Two years after the filtering tank was put in place, it is apparent that the alum feed system, even as it was promoted by both U.S. and Honduran groups and community members, is seldom, if ever, used. For the operator, however, the system was the basis of a job for which he was seen by the community as uniquely qualified. This operator explained to me that he wasn’t paid enough for the job he did and I watched him ‘set up’ the aluminum sulfate feed system (with him knowing that I was watching him) although I knew that the system had not been used, and was not going to be used. With the solar oven project in Nicaragua, a similar constellation of U.S. based university engineering students and Professors works with both a university based group and a community based NGO. Again, the U.S. group is concerned to portray its work to the wider engineering college that the project is technical and scientific. A newly built, computer controlled test facility is often featured in this regard in portrayals of the project by the U.S. university engineers. With regard to the Nicaraguan groups and communities, my research is still quite preliminary. However, it is apparent that a the community based NGO has taken on a role of teaching and promoting technological aspects of energy systems as well as the solar ovens to community members and the idea that solar ovens are part of a larger advanced technology movement that the group is positioned to bring to the community seems to be an important framing point. The situatedness of the Nicaraguan University group with respect to its own University at large is yet to be explored in this regard. Of what use is it to take the ‘technicalness’ of ‘development’ technologies as a constructed aspect of intervention? The motivation for this approach is to explore a means by which Science and Technology Studies can speak to histories of technology and engineering. There is a large literature in the social construction of technology, including recommendations from social constructivists for analysts of engineering to consider the social construction of technology in their work. This approach is different From that in that it seeks to trace participants own parsing of ‘the technical’ and ‘the social’ in order to bring out the relations of authority and control involved in ‘technological’ projects. Along the lines of promoting an understanding of the social construction of technology, Johnson and Wetmore have asserted that what engineers need to understand is that STS has discredited the technological deterministic conception of technological development and that “social and technical aspects of the world are intimately interwoven and change in concert (and) socio-technical systems should be the unit of analysis in technology and engineering studies.”1 According to these authors, engineering ethics needs to incorporate this idea into its considerations: technology has meaning only in a life-world of practice. When this is understood by engineers, 1 Johnson and Wetmore. “STS and Ethics.” engineers in practice will be able to ask the right kinds of questions with regard to just how, socially, technology should be constructed. This approach follows from an earlier call in STS with regard to intervention from Woodhouse, et al. al. Again, given that STS has determined that technology is socially constructed, the STS scholar and practitioners should then push on to the questions posed by Patrick Hamlett: “How should technologies be constructed? Which relevant ‘social groups’ ought to be included in the process? Are there morally preferable ways for the creation of technological frames? How should interpretive flexibility come to closure? When and how should closure be re-opened?”2 In doing so, the scholar should not be afraid to put scholarship in the service of social justice with regard to the answers. But, again, how do we reconcile that promotions of the nature technology are part of technological practice itself? This paper wrestles with the issues confronting both practitioner and analyst with regard to portrayals of engineering as ‘technical’ and points toward a new approach to considering relations of authority and control through the lens of ‘the technical’ through examples of current technology project in progress. On the face of it, it is absurd – of course technological projects are technological! But opening up the various means by which the technicalness of technology projects are asserted and enforced could be an important historiographical method. 1. D.G. Johnson and J. Wetmore. “STS and Ethics: Implications for Engineering Ethics.” in The New Handbook of Science and Technology Studies, edited by Edward Hackett, Olga Amsterdamska, Michel Lynch, and Judy Wajcman. London: Sage, 2007. 2. Edward Woodhouse, David Hess, Steve Breyman, and Brian Martin. “Science Studies and Activism: Possibilities and Problems for Reconstructivist Agendas.” Social Studies of Science 32/2 (2002): 297-319. 2 Woodhouse, Hess, Breyman, and Martin. “Science Studies and Activism.”