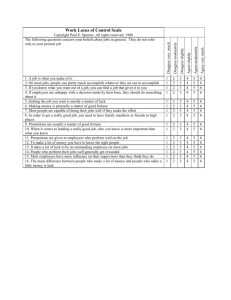

Section II. The Bargaining Problem

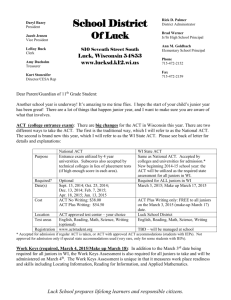

advertisement

Luck, Leverage, and Equality: A Bargaining Problem for Luck Egalitarians Roger Ford has a seasonal job in Caro, Michigan, stacking 100-pound bags of sugar. He makes $8 an hour with no benefits. The winter mornings are bright and harsh in the small town north of Detroit near the shores of Lake Huron, and he often wakes before dawn with back spasms from the previous day’s lifting. He does not have health insurance to pay for prescription medication, and cannot afford to miss a day of work. Ford is 52 years old, and worked for Lear Corporation for over two decades until he was laid off last year, a casualty of the recent economic downturn. “I’m going in reverse and I don’t understand why,” he told a reporter for the United Auto Workers. He took the part-time job at a Oxford Philosophy Conference Submission pg. 2 loading dock after months of searching for a better one. “I had no choice,” said Ford. “I had bills, obligations. I went from having a life and feeling like a human being, to feeling like some kind of uneducated slave working my fanny off for peanuts.”1 The notion of choice is essential for luck egalitarians. It plays a crucial role in their conception of the justice of distributional inequalities. The distribution that grants Roger Ford so little is just only if his disadvantage is the result of his choices. Whether he had no choice in taking the job at the loading dock, as he claimed, thus determines whether he is entitled to compensation or assistance from the state. Compassion demands that we help him. It is not obvious, however, whether Ford really made a choice. There is a political and social sense in which he was denied choice. But in the raw metaphysical sense, it seems that he still chose to take the job rather than remain unemployed. While the distinction between choice and chance is stark in theory, the complexities inherent in actual cases render it obscure. The intuitive appeal of the distinction serving as the luck egalitarian criterion of justice consequently fades in light of the dynamics of real economies. In this paper I will discuss a problem with the luck egalitarian position that only becomes apparent when distributions are considered in light of economic interactions occurring over time. Roger Ford trades his labor for $8 an hour, because his other options are even less bearable than this job. I aim to show that he is treated unfairly, and that the luck egalitarian is unable to account for the injustice of his situation. 1 Adapted from the December 2003 issue of “Struggling to Survive,” available at the UAW website, www.uaw.org. Oxford Philosophy Conference Submission pg. 3 Section I. Luck Egalitarianism The luck egalitarian provides a set of criteria for distributions based on the idea that inequalities are unjust if they derive from mere luck. This class of theories was inspired by, but is importantly different from, the scheme developed by John Rawls in A Theory of Justice.2 Luck egalitarian theories follow Rawls’ basic liberal framework. The goods of society are not initially tied to particular individuals, and so can be redistributed however the ideal distribution demands through taxation or other means. This framework is in opposition to conservative theories like Nozick’s that give primacy to individual property rights.3 Rawls, in his informal argument for the principles of justice, introduces the further idea that some factors are “arbitrary from a moral point of view”, and therefore cannot justify inequalities.4 The Difference Principle, however, maximizes the position of the worst-off without regard to the source of inequalities. The question of whether Rawls is committed to luck egalitarianism but did not realize it is beyond the scope of this paper; what is beyond dispute is that the luck egalitarian tradition took Rawls as its starting point. The central principle of luck egalitarianism is that people should be treated as equals, and as such they ought to be insulated from certain kinds of misfortune.5 People deserve the results of their decisions and actions, but do not deserve the results of factors external to them. Thus, one role of the basic institutions of society like the state is to 2 Rawls, A Theory of Justice. Robert Nozick, Anarchy, State, and Utopia. 4 Rawls, A Theory of Justice, pg. 72. 5 Arneson, Rakowski, Cohen, and Dworkin are among the most prominent luck egalitarians. I consider a paradigmatic luck egalitarian view that may not be attributable to any one luck egalitarian in particular. Rakowski, in conversation, has stressed that the luck egalitarian principle is only one in a plurality of principles of distributive and overall justice. For an opposing view, see Anderson (1999) and Scheffler (2003). 3 Oxford Philosophy Conference Submission pg. 4 redistribute resources from those who are advantaged by chance to those who are disadvantaged by chance until the effects of luck are extinguished. The inequalities that survive this redistribution are the result of choices, and are therefore just. Under this scheme, a farmer who is poor due to a local drought is due compensation because the drought is a matter of chance. If, on the other hand, the farmer made risky crop decisions that did not turn out as he had hoped, he is not due any compensation because the resulting inequalities are the result of choices he made. Ronald Dworkin introduced hypothetical insurance markets using this distinction between “option luck” and “brute luck” to justify certain levels of state compensation.6 G. A. Cohen then argued that the luck distinction is itself underwritten by the distinction between “choice” and “chance.”7 All luck egalitarian theories rest on the notion that some factors are not deeply attributable to individuals, and that inequalities deriving from such factors are not just. This fundamental notion has intuitive force. A primary concern of justice is fairness, and it seems unfair that the material wealth of individuals should depend on brute luck or chance. It is not the farmer’s fault that a drought ruined his harvest, so he should not have to bear the burden alone. It was entirely out of his control, and in a sense could have happened to any of us. Natural disasters are the paradigm example of a morally arbitrary factor. Since it could have happened to any of us, fairness dictates that we bear the burden together. Advantages that arise from pure chance are similarly arbitrary, and thus should be enjoyed by us all equally. This communitarian impulse ceases when we consider the effects of choices that people make. If the farmer had decided to sit on his couch all day instead of harvesting his crops, we would be less 6 7 Dworkin, “Equality of Resources,” reprinted as Chapter Two of Sovereign Virtue. G. A. Cohen, “On the Currency of Egalitarian Justice,” Ethics 99 (1989): 906-44. Oxford Philosophy Conference Submission pg. 5 inclined to compensate him when they rot in the field. It would have been his choice to sit on his couch, and since he would have no one to blame but himself for his disadvantage, he would have no claim on the resources of others. Since the farmer’s misfortune would be entirely the result of his decision, what he reaps is what he sows. The debate among luck egalitarians has centered on two issues.8 First, it is not clear what ought to be equalized in order to treat people like equals. The two main positions on this issue are equality of resources and equality of welfare.9 Dworkin and others argue that everyone’s share of resources should be equalized, up to the inequalities deriving from choice. The problem of expensive tastes is a prominent argument in favor of this position.10 Cohen and others argue that instead everyone’s welfare should be equalized, again up to the inequalities deriving from choice. They point to the symmetry between expensive tastes and handicaps, and to the fact that welfare rather than resources is what we care about in the first place. Resources have only instrumental value insofar as 8 Anderson (1999), Scheffler (2003), and Wolff (1998) have criticized the luck egalitarian project. They argue that the role of the state is to ensure political and social equality, and the state ought only be concerned with the distribution of resources insofar as these distributions influence these other values. This leads Anderson, for example, to adopt a ‘sufficientarian’ position. 9 There are other permutations as well: equality of access to advantage, equality of opportunity, equality of advantage, and so on. Most proposals fall roughly under one or the other of the main headings. 10 Dworkin, “Equality of Welfare,” reprinted as Chapter One in Sovereign Virtue. Dworkin’s main argument depends on the action of hypothetical insurance markets. Others, for example Cohen, have dropped this argument from the subsequent restatements of the position. Dworkin in turn has adopted Cohen’s formulation of the choice-chance distinction. His position on the role of hypothetical insurance markets in relation to the distinction is thus unclear. Dworkin’s position in “Equality of Welfare” is luck egalitarian insofar as he thinks people would insure in the hypothetical market only against chance factors. If he abandons this claim, then he is free of the problems that accompany the choice-chance distinction but owes a different account of the hypothetical insurance markets. See Section III. Oxford Philosophy Conference Submission pg. 6 they affect people’s well-being.11 The debate about this first issue and its outcome is irrelevant for the purposes of this paper. The second debate focuses on the distinction between choice and chance, and is of central importance to my argument. It is not clear what is to count as choice and what is not. Most can agree that the wealth and social position of one’s parents is in no way a matter of choice since they were determined prior to birth, and therefore count as elements of chance. Other factors are not so obvious. Character traits like laziness, determination, and persistence can have a profound effect on economic distributions and are not chosen in any straightforward sense. Nonetheless, many believe that these traits are deeply attributable to individuals and thus justify inequalities. The situation is further complicated by worries about determinism. If people’s choices are themselves caused by antecedent factors – like education, upbringing, and genetics – then we may be tempted to doubt that there are any choices at all of the required kind. As Cohen remarks, using the distinction between choice and chance as the criterion for just inequalities renders luck egalitarians “up to [their] necks in the free will problem.”12 In order for the distinction to bear the great weight they place on it, luck egalitarians must provide a coherent account of what counts as choice rather than chance, and specify what it is about those choices that justifies inequalities. I wish to discuss a difficulty for luck egalitarianism that does not depend on the metaphysics of the will. In the next section I will present a bargaining problem. This bargaining problem is meant to bring out features of the choice-chance distinction that are deeply problematic prior to any concerns about free will. I will argue that it shows 11 See, for example Arneson, “Equality and Equal Opportunity of Welfare,” Philosophical Studies 56 (1989): 77-93. 12 G. A. Cohen, “On the Currency of Egalitarian Justice,” Ethics 99 (1989), pg. 934. Oxford Philosophy Conference Submission pg. 7 how natural economic interaction generates intuitively unjust distributions. These sorts of interactions are ubiquitous in complex societies, and therefore the problem pertains to contemporary public policy. For the sake of simplicity, however, I will relocate the bargaining problem to a small desert island. The problem straightforwardly generalizes to more complex societies, and inequalities swell as economic interactions compound. But the basic structure of the problem, we shall see, is evident in the simplest of economies. Section II. The Bargaining Problem Imagine that a raft of 10 shipwreck survivors lands on a small and uninhabited desert island. Since it is a desert island, the only source of food is fish. After landfall, the survivors decide to set up a society. They divide all the resources of the island equally, such as land and fishing rights. Assume that survivors all have comparable native talents and dispositions, so that there are no inequalities whatsoever.13 Assign each survivor’s resource bundle a value of 5. We suppose then that this initial distribution of resources is just according to the luck egalitarian. After the initial distribution, there is no cooperation as each tries to make it on his own. Nine of the survivors try to subsist by catching small fish near the shore. One of the survivors, Gates, tries a riskier fishing strategy. His risky decision pays off when he hauls in a medium-sized whale. The other survivors, however, have not fared as well. There simply are not enough small fish to feed them, and are going hungry. Gates’ resource bundle has grown to 20 due to his whale catch, while the rest of the survivors still have only 5. Since this inequality derives solely from the choices 13 As I have described the situation, there are no inequalities in resources. Alternatively, we can set up the case using a welfare metric. See Note 15 for the translation. Henceforth in the text I will speak in terms of resource, with the understanding that the same problem applies to a welfare theory. Oxford Philosophy Conference Submission pg. 8 of Gates and the other survivors, it is considered just on the luck egalitarian theory. Gates’ whale catch is a paradigm example of option luck. He decided to take a risk that might have resulted in an empty haul or in drowning, but actually netted him a windfall. Once Gates returns from his whaling trip, the other survivors (henceforth just “the survivors”) want to trade with him for some of the whale meat. At the bargaining table, Gates and the survivors are in importantly different positions. Gates is willing to walk away without a deal, but the survivors cannot. Since they are faced with the prospect of starving, the survivors are willing to agree to deals that they would not otherwise have made. Knowing this, Gates is only willing to agree to deals that are heavily in his favor, and to which the others would not agree under normal circumstances.14 Say, for example, that Gates gets half of all future resources produced by the survivors in exchange for a unit each of whale meat. From Gates’ perspective, if the survivors turn down his proposal he misses out on the advantages of the potential deal, but he will live. From the survivors’ perspective, if Gates turns down their proposal they will starve. As a result, Gates doesn’t have to compromise because he knows they will eventually agree to his proposal. And since their only other option is to starve, they eventually choose to do so.15 Once the deal is made, the survivors do not starve but must give Gates half of the resources they 14 We can assume that neither party threatens or attempts to coerce the other. Specifically, Gates does not coerce the survivors or threaten them with starvation. He is not responsible for the fact that if they refuse his offer they will starve; he merely alters his offer in light of this. 15 The case in welfare terms is as follows: due to option luck, Gates has more welfare than others. If no deal is struck, both parties will have lower welfare than they would have if a deal were made. Gates’ welfare will be just high rather than very high. The others’ welfare will be zero rather than very low. Gates’ can live with just high welfare, but the others cannot live with zero welfare. Thus Gates’ bargaining position is better, and he can hold out for an advantageous deal. Oxford Philosophy Conference Submission pg. 9 produce. So some time later, Gates has 121 resource units, while the survivors have only 16 each.16 Is this distribution just? Intuitively, the answer is no. Moreover, the distribution is unjust on egalitarian grounds. The survivors have not been treated fully as equals in their dealings with Gates. The problem is that he had bargaining leverage over the survivors. One party has leverage over another when they have a positional advantage. Due to this advantage, they are able to influence interactions with the other party in ways that would be impossible if their positions were equal. The leverage in this bargaining problem derives from the fact that people are willing to make different deals depending on the context and circumstances of the decision. Gates’ decision is made in the context of wealth, whereas the survivors’ decision is made in the context of potential starvation. The final distribution is a direct result of Gates’ leverage over the survivors. If they had not been faced with the prospect of starvation, they would have held out for a much better deal. Perhaps they would have paid only 1 resource each for the whale meat, a deal Gates would have made if he knew he could not get any more. The final distribution would then have Gates with 40 resource units, and the survivors with 25 each. They are not leveraged, and this inequality might have been just since it derives solely from Gates’ good option luck. The further inequality, which derives solely from the leverage Gates exercised over the others, is unjust. 16 To arrive at this distribution, suppose after the bargain everyone produces 20 units each. Gates would then have 20 units from prior to the bargain, minus the 9 units of whale meat he gave the others, plus 20 he produced post-bargain plus 10 each from his half of the nine others’ production, for a total of 121. The other survivors would each have 5 from prior to the bargain, plus one of whale meat, plus 10 from their half of their own production, for a total of 16. Oxford Philosophy Conference Submission pg. 10 The bargaining problem is a prima facie counterexample to luck egalitarianism. The inequalities in the post-bargain distribution derive solely from the choices of Gates and the survivors. Gates chose his risky fishing strategy, and the survivors chose to accept Gates’ proposed deal. Since inequalities deriving from choices are just according to the luck egalitarian, it is unclear on what grounds he could count the final distribution of the bargaining problem as unjust. One strategy is to deny the intuition that the final distribution is unjust. If the luck egalitarian can provide a compelling argument that our intuitions on this case are mistaken, then the putative counterexample is disarmed. A second strategy is to show how the luck egalitarian theory in fact agrees with the intuition that the final distribution is unjust. If the luck egalitarian can show that the inequalities are the result of chance, then the bargaining problem is deflected. In the next section I will consider these two strategies for the luck egalitarian in response to the bargaining problem. Section III. Responses There is a strong intuition that the post-bargaining distribution is unjust on egalitarian grounds, rooted in the observation that the survivors end up with less than they would have if Gates had not leveraged them at the bargaining table.17 As a first strategy the luck egalitarian might nonetheless claim that the post-bargain distribution is entirely just. On the luck egalitarian theory, it must then be that the inequalities in that distribution arise from option luck or choice. In one sense, this is clearly the case. The survivors were not compelled or coerced when they agreed to Gates’ proposal. The final 17 Henceforth, ‘just’ and ‘unjust’ are abbreviations for ‘just on egalitarian grounds’ and ‘unjust on egalitarian grounds,’ unless otherwise noted. Oxford Philosophy Conference Submission pg. 11 distribution was a result of their choice to enter into the deal. The luck egalitarian might thereby conclude that the inequalities in this distribution are just. However, the survivors were in a particular bargaining position when they chose to enter into the deal with Gates, and the final distribution is a result both of their antecedent position and their choice once in that position. If a gambler is forced to play a game he cannot win, the game is still unfair despite the fact that he chooses the particular outcome. If the survivors’ bargaining position is a matter of brute luck, then the fact that they chose to enter into a deal from that bargaining position does not alone render the final distribution just. Thus, in order to maintain against intuition that the final distribution is just, the luck egalitarian must show how the survivors’ bargaining position itself resulted from choice. The bargaining problem arose because of Gates’ good option luck, and so his leverage over the others derives from his choice. The eventual inequalities were in turn the result of this leverage, and so derive from his good option luck. Thus, the luck egalitarian might claim, the inequalities in the final distribution are just. This answer is not satisfying because Gates’ good option luck is, from the perspective of the survivors, a matter of brute luck.18 No choice of theirs gave rise to his windfall or his decision to leverage them. So if they find themselves in a weak bargaining position due to his good option luck, then the eventual inequalities are not the result of their choices. It is not consistent for the luck-egalitarian to hold that the post-bargaining distribution is just if the survivors are victims of brute luck in the form of someone else’s good option luck.19 18 There is a sense in which Gates’ good option luck is good brute luck for the survivors; if he hadn’t caught the whale, he would have no food to trade them and they would all die. So the bad brute luck they suffered is when Gates’ decided to leverage them. 19 This alone may be reason enough to reject luck egalitarianism. There are two sides to every inequality; rewarding the good option luck of one party may constitute bad brute Oxford Philosophy Conference Submission pg. 12 He must further claim that they landed in a weak bargaining position as a result of their own choices. There is a sense in which the survivors’ bargaining position is a direct result of their own choices. They chose their fishing strategy, and thus their poor catch is a matter of option luck. Their level of resources at the bargaining table is the root of their poor bargaining position, and since the former is the result of option luck, then so is the latter. They are vulnerable to Gates’ leverage because of their bad option luck, and thus the inequalities that result are just. But this isn’t the whole story. Their weak bargaining position is not solely the result of their bad option luck; it is also the result of Gates’ good option luck. If he had not done so well, then he would not have had leverage over them. Leverage is a relational property between two positions, and is therefore defined in terms of both positions. Thus their bargaining position is a function both of their resource level and of Gates’ resource level. Since the latter is not the result of any choice of theirs, their bargaining position is at least in part a matter of brute luck. These considerations render the denial of the intuition implausible, but suggest a solution for the luck egalitarian. The second strategy for the luck egalitarian is to accept the intuition that the post-bargaining distribution is unjust, and explain this injustice by showing that the survivors’ bargaining position was a result of brute luck. This is a promising line of thought because it seems to capture the spirit behind the intuition about luck for another party. The luck egalitarian seeks to evaluate distributions separately with respect to each individual. But distributions are the result of everyone’s choices and everyone’s luck taken together. So when we say a distribution is said to be the result of choice or chance, we must further ask: whose choice and whose chance? Because individual fortunes are not separable in the way the luck egalitarian seems to assume, it may not be coherent to say that a distribution is due to either choice or chance. Michael Titelbaum clarified this point to me. Oxford Philosophy Conference Submission pg. 13 the bargaining problem; the survivors were subject to circumstances outside of their control that led to great inequality, and thus the final distribution is unjust. This response is structurally similar to G. A. Cohen’s observation that it is a matter of bad brute luck for the champagne connoisseur that his tastes happen to be expensive.20 Only due to factors outside of their control is their decision to trade with Gates – or not to trade with him – so costly. Gates’ leverage renders each of their options at the bargaining table more expensive than otherwise they would have been. Thus the outcome of the survivors’ decision at the bargaining table is a hybrid result arising from the joint action of choice and chance. One way to see this is to notice that their decision is more like a multiplechoice question than it is like a fill-in-the-blank. Circumstance has presented them with a limited number of options, and they are forced to make their choice from those options. The option set is in large part the result of external factors, and thus the inequalities that arise from choice from this option set are unjust. The luck egalitarian seems to have answered the challenge posed by the bargaining problem by showing how the intuition that the post-bargain distribution is unjust can be explained solely by reference to the distinction between choice and chance. But if the survivors’ bargaining position is a matter of brute luck then so is Gates’, and moreover any other bargainer with any level of resources. Gates is no more in control of the option sets presented to him by circumstance than are the survivors. Thus if the luck egalitarian grants that the survivors’ bargaining position count as the sort of chance that renders inequalities unjust, then he must admit that all bargaining positions do. Since all bargaining positions are a matter of chance, then every trade is tainted with an element 20 Cohen, “Expensive Taste Rides Again.” A connoisseur may be responsible for a preference for champagne, but not for the fact that champagne is so expensive. Oxford Philosophy Conference Submission pg. 14 of brute luck. The upshot is that all inequalities arising from economic interaction are unjust. More broadly, no one is ever the sole author of their option sets, so no decision counts as the robust sort of choice that justifies inequalities. Even the paradigm example of option luck, a risky gamble, counts as chance. For the gambler’s option set, consisting of the probabilities and the payoffs and even the option of walking away from the table, are collectively determined by circumstances outside his control. The category of option luck is thus rendered empty, and even incoherent. This result is problematic in at least two ways. First, since there are no instances of option luck, there are no justifiable inequalities deriving from bargains. Since most inequalities in a complex society pass through bargains at some point, very few if any inequalities would survive. While some philosophers, like Cohen, might embrace this result, most would not accept it. The reason is that the original intuition behind the primacy of the distinction between choice and chance was that it would sometimes be reasonable to hold people responsible for their decisions, and allow inequalities that result. While the great inequalities that exist today are no doubt unjustifiable, the luck egalitarian is apt to think that some relatively minor inequalities are acceptable due to the action of some kind of choice. Second, grounding a moral distinction in this analysis of choice is dubious. It is implausible to excuse a murderer simply because his option set was fixed externally. It is important to note that the luck egalitarian response at this point is not the standard incompatibilist position. The problem is not that the murderer’s decision is externally determined, but that his option set is. The position is ecumenical with respect to the free will debate; even if the will is radically free and determinism is false, the problem remains. The luck egalitarian must deny that some decisions are deeply Oxford Philosophy Conference Submission pg. 15 attributable to agents even though their option sets are largely a matter of chance. He then ignores the important moral difference between a murderer whose only other option was to die himself, and a murderer who had other less odious options. To say that the options open to an agent are to a certain extent defined by chance does not wholly eliminate the hand the agent has in producing the outcome. In the case of bargaining positions, there are still instances where choice leads to justifiable inequality. Suppose two bargainers have equal bargaining positions, so neither has leverage over the other. For whatever reason, a whim or a fancy, they agree on a deal that is more advantageous to one party. While the final distribution may be regrettable for the losing party, it does not seem unjust. More precisely, if it is unjust, it is not so because the option set was externally determined. If in response to the bargaining problem the luck egalitarian expands the category of brute luck to include option sets and so all inequalities are rendered unjust, then forgotten is the important difference between agents who choose wisely, those who choose poorly, and those who do not choose at all. The luck egalitarian is left with an implausible conception of choice and chance, and a distinction that cannot count as the primary criterion for just distributions. As a final strategy, the luck egalitarian may reply that there is another sense in which some option sets render a putative choice insufficiently robust to justify inequalities. It is not their external determination, a feature that is shared by all option sets, that is relevant to the justice of distributions. Rather, the content of some option sets constrains agents in such a way that their putative choices no longer count as robust choices that can justify inequalities. Some option sets are internally structured such that they do not constrain agents in this way, and thus inequalities that arise from those sorts Oxford Philosophy Conference Submission pg. 16 of option sets are just. The problem with the survivors’ bargaining position was not that the option set was externally determined, but that the options open to them were systematically unattractive. Moreover, the option set was negatively and deliberately influenced by the manipulation of another agent. The distinction between choice and chance thus rests not on the mere fact that an option set is externally determined, but on the content of the option set and the particular factors that brought it about. The luck egalitarian hopes to sort option sets into two categories: the kind that allows the possibility of legitimate choice, and the kind that does not. What counts as a choice and what counts as a chance is thus determined in part by the moral character of the option set from which the putative choice was made. While this answer saves the luck egalitarian from the pathological position on the nature of choice and chance we saw above, it does so at the cost of sacrificing the primacy of the distinction. The distinction between choice and chance was meant as the fundamental criterion for the egalitarian justice of distributions. This requires that the distinction have independent validity, which can in turn support the moral judgments the luck egalitarian draws from it. We must then have a prior understanding of what counts as a choice and what counts as chance. This prior understanding will be grounded in the nature and structure of the will. But we saw that since the survivors’ putative choice is legitimate on this understanding, the luck egalitarian erroneously counts the post-bargain distribution as just. As a result, he must expand the category of chance to include the survivors’ situation. The only ground for doing so is the content of their option set. This strategy thus takes our judgments about the moral character of option sets as fundamental, and these judgments then inform what counts as choice and chance. We Oxford Philosophy Conference Submission pg. 17 have no independent reason to think that the character of option sets is intimately connected with the metaphysical status of a putative choice. We know only that certain sorts of option sets allow for just inequalities arising from putative choice and others do not, and that the luck egalitarian theory takes the distinction between choice and chance as the criterion for egalitarian justice. The luck egalitarian could define choice and chance in terms of the moral character of option sets. But whether this criterion was valid is precisely the question we aim to answer. Without independent reason to take inequalityjustifying option sets as giving rise to choice, and all others as giving rise to chance, we have no reason to accept the luck egalitarian criterion in the first place. Our primary intuition is that in cases of putative choice some types of option sets render downstream inequalities unjust. The character of these option sets does not alter or constitute the metaphysical status of the putative choice; they only affect the justice of resulting inequalities. The survivors did in fact make a choice; the outcome is unjust not because this choice failed to be “real” or “robust” but because it was made in the context of unfair circumstances. The fact that these circumstances were unfair cannot be explained in terms of whether they gave rise to robust choice. Instead, it must be explained in terms of autonomous political, social, and economic ideals. Certain forms of political equality are necessary preconditions for the evolution of just distributions, but the absence of such equality does not undermine the metaphysical status of putative choices. Consider, for example, a racially segregated society. Because it lacks political equality, this society generates unjust distributions that systematically favor the members of one race. The option sets presented to the members of the disadvantaged race are categorically different than those presented to the members of the advantaged race. This Oxford Philosophy Conference Submission pg. 18 constitutes a deep violation of basic political fairness, but it does not necessarily change the metaphysical status of putative choices made by those in the worst positions of society. It is a paternalistic insult to the disadvantaged to suppose that they are incapable of legitimate choice merely in virtue of their position. The sort of freedom that is lacking is political freedom, not metaphysical freedom. There are undoubtedly extreme political and social conditions that would undermine the metaphysical status of the putative choices made by some members of society, but this cannot be explained so simply as pointing to the fact that these conditions are unchosen. This is, as Cohen points out, a question of the metaphysics of the will. However, there are some distributional inequalities that cannot be traced to such extreme, freedom-destroying conditions but are nonetheless unjust. The inequalities in a moderately racially segregated society are one example. In a well-ordered society, most objectionable inequalities will be unjust in virtue of political and social ideals rather than the absence of metaphysical choice. Pricegouging, unfair labor practices, disproportionate tax relief to the wealthy, and monopolistic trade practices all lead to unjust, inegalitarian distributions but do not wholly undercut the agency of the disadvantaged. The luck egalitarian theory, insofar as it is committed to the primacy of the distinction between choice and chance, is unable to explain the injustice of these inequalities. The case of the bargaining problem accentuates this shortcoming of the luck egalitarian theory. By hypothesis, the survivors’ choice to enter into the deal was free and uncoerced. While it is possible that conditions would be so extreme as to undermine the metaphysical status of their putative choices, the bargaining problem concerns the case in which conditions made for a painful but still legitimate choice. Nonetheless, the final Oxford Philosophy Conference Submission pg. 19 distribution that results from their choice is unjust. This injustice is explainable only in terms of autonomous political and social ideals. The conditions that preceded their choice were unfair from this standpoint, and that failure alone renders the final distribution unjust. Their situation is objectionable because Gates took advantage of the survivors. He did not force or coerce them, so the prior assignment of basic rights and liberties traditionally accepted by luck egalitarians does not forbid his action. In order to explain the intuition that Gates’ bargaining practice was unfair, and to justify its prohibition, we must accept the principle that bargains are fair and can therefore justify inequalities only if the parties have substantially equal bargaining positions. This principle cannot itself be explained in terms of the choice-chance distinction. Consider, for example, the minimum wage. The minimum wage forbids certain deals between employers and workers, even if the workers would agree to them. One justification for this is that some deals would be unfair and lead to unjust distributions, even if both parties freely chose to enter them. The regulation of bargaining, both through the prohibition of certain deals and through taxation, compensates those who would have less because of their weak bargaining position. This amounts to accepting the principle of equal bargaining positions as an autonomous social and political ideal. Part of what it means to treat citizens as equals, then, is to ensure that the final distribution reflects the deals that would have been made if all parties had substantially equal bargaining positions. In contrast to Anderson’s and Scheffler’s recent critiques of luck egalitarianism, which show that a fair distribution is a precondition of political equality, the bargaining problem shows that a degree of political and social equality is a precondition for fair distributions. The upshot of these two angles of critique is that distributive justice cannot Oxford Philosophy Conference Submission pg. 20 be considered in isolation from political and social equality. If the distinction between choice and chance is expanded to account for our intuitions about the final distribution in the bargaining problem, then the distinction no longer tracks independent and intuitive notions of choice and chance and thereby loses its explanatory priority. If the luck egalitarian retains a more philosophically responsible conception of the distinction, his theory of justice must incorporate autonomous social and political ideals in order to explain why the survivors are not treated fairly as equals. Either way, the bargaining problem shows that the paradigmatic luck egalitarian position lacks the conceptual apparatus to account for a basic and important type of distributional inequality. Section IV. Conclusion – The Limits of the Market Luck egalitarianism expresses faith in the justice of the market. It is founded on the idea that market agents generate just distributions via free transactions. Luck egalitarianism interferes with the action of the market only by neutralizing the effects of unchosen circumstance – by leveling the initial playing field and by counteracting instances of brute luck as time passes. It thereby hopes to purify trade conditions so we might more closely approximate the natural justice of the market by tracking only the effects of choice. But the bargaining problem shows that we cannot rely on the market, even in its purified form, to produce justice. Injustice enters the market at the outset and operates through the actions of individual market agents, and so becomes inseparable from the legitimate effects of trade if all we observe are the choices of market agents. This is simply because, in the face of injustice, people still try to do the best they can. Leverage is a pervasive problem in contemporary society. The emergence of the corporate form and speculation on borrowed capital in particular has generated enormous Oxford Philosophy Conference Submission pg. 21 gaps between the bargaining positions of the wealthy and the poor. Some of this phenomenon can be traced to inequalities of unchosen features like talent and social class, but a significant portion derives from leveraged bargains. The resulting distribution of wealth is unjust, despite the fact that it can be traced to the legitimate choices of the disadvantaged. Roger Ford’s choice to work at the loading dock in Caro, Michigan, while legitimately a choice, does not amount to an endorsement of his poverty, any more than the survivors’ deal with Gates amounts to an endorsement of the post-bargain distribution. That Ford had to make that choice in order to survive itself reflects the hardship of his position. Inequalities evolve through the choices of the disadvantaged like Ford, but this does not make those inequalities just. A reasonable social and political ideal will compensate him because of the moral character of his option set. It is not until we examine the array of options that were available to the disadvantaged that we can begin to understand their situation. The injustice that faces Roger Ford each morning as he loads the idling trucks at dawn is undeniably real, because his choice to work was desperate, and made from a set of options that denied him political and social equality.