Artful Encounters with Nature - University of Illinois at Urbana

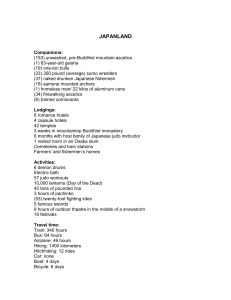

advertisement