Chapter 4

advertisement

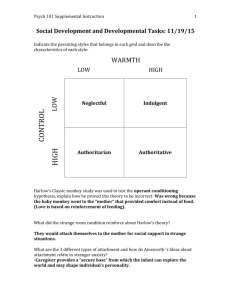

Chapter 4 Attachment: Learning to Love Chapter Outline 4. ATTACHMENT: LEARNING TO LOVE THEORIES OF ATTACHMENT PSYCHOANALYTIC THEORY LEARNING THEORIES COGNITIVE DEVELOPMENTAL THEORY ETHOLOGICAL THEORY Insights from Extremes: Maternal Bonding HOW ATTACHME NT DEVELOPS FORMATION AND EARLY DEVELOPMENT OF ATTACHMENT WHAT IT MEANS TO BE ATTACHED Learning from Living Leaders: Michael E. Lamb ATTACHMENT TO WHOM? Bet You Thought That . . . Babies Become Attached to Their Teddy Bears and Blankets THE NATURE AND QUAL ITY OF ATTACHMENT DIFFERENT TYPES OF ATTACHMENT RELATIONSHIPS Ainsworth’s Classification of Attachment Types Beyond Ainsworth’s A-B-C Classification Other Strategies for Assessing Attachment Learning from Living Leaders: Everett Waters Cultural Context: Assessing Attachment in Different Cultures Attachment Types and the Brain PARENTS’ ROLE IN INFANTS’ ATTACHMENT DEVELOPMENT Biological Preparation Link between Caregiving and Attachment Research up Close: Early Experience, Hormones, and Attachment Attachment in Family and Community Contexts Continuity in Attachment from Parent to Child Attachment of Children in Child Care Real-World Application: Attachment When Mother Goes to Prison EFFECTS OF INFANT CHARACTERISTICS ON ATTACHMENT STABILITY AND CONSEQUENCES OF ATTACHMENT STABILITY AND CHANGE IN ATTACHMENT OVER TIME ATTACHMENTS IN OLDER CHILDREN CONSEQUENCES OF ATTACHMENT Associations with Exploration and Cognitive Development Implications for Social Development Learning from Living Leaders: L. Alan Sroufe Consequences for Self-Esteem Attachments to Both Mother and Father Are Related to Later Development Attachment or Parenting: Which Is Critical for Later Development? Into Adulthood: From Early Attachment to Later Romantic Relationships Chapter Summary KEY TERMS At the Movies Learning Objectives 1. Define attachment. 2. Understand the different theories of attachment (psychoanalytic, learning, cognitive, and ethological). 3. Define concepts of imprinting, secure base, and maternal bond. 4. Describe the four phases of attachment development according to Bowlby (preattachment, attachment in the making, clear-cut attachment, goal-corrected partnership). 5. Describe what it means to be attached (e.g., seeking of proximity, separation distress or protest). 6. Explain why infants usually form their first attachment with the mother. Discuss the necessary conditions for forming an attachment with others (e.g., familiar, frequent, positive). 7. Discuss the special role of father-infant attachments. 8. Describe the Strange Situation for assessing the nature and quality of attachment. 9. Describe Ainsworth’s categories of attachment (secure, insecure-avoidant, insecureambivalent). 10. Describe the insecure-disorganized attachment pattern. 11. Explain other strategies for assessing attachment (coding behavior in Strange Situation, Attachment Q-Set, California attachment procedure). 12. Understand the links between attachment type and brain development 13. Understand the parents’ role in attachment (biological preparedness, caregiving patterns, role of family and community contexts). 14. Define the internal working model and discuss continuity in attachment from parent to child as assessed by techniques like the Adult Attachment Interview. 15. Discuss the role of child care in attachment. Provide possible explanations for the higher rates of insecure attachments among children in full time child care. 16. Describe the effects of infant characteristics on attachment. 17. Discuss the stability in attachment over time and provide explanations. 18. Discuss attachment in older children and the changing relationships between parents and children over time. 19. Understand the consequences of attachment for cognitive, social, and self-esteem development. 20. Explain whether the consequences of attachment can be attributed to the attachment quality itself or to ongoing parenting quality and parent-child relationships. Student Handout 4-1 Chapter Summary During the second half of the first year, infants form attachments to the important people in their lives. Theories of Attachment According to the psychoanalytic view, the basis for the infant’s attachment to mother is oral gratification. According to the learning view, the mother becomes a valued attachment object because she is associated with hunger reduction. According to the cognitive developmental view, before they develop an attachment, infants must be able to differentiate between mother and a stranger and must be aware that the mother continues to exist even when they cannot see her. Bowlby’s ethological theory of attachment stresses the role of instinctual infant responses that elicit the parent’s care and protection and focuses on the way the parent acts as a secure base. The maternal bonding theory suggests that the attachment the mother feels to her infant is affected by early mother-newborn contact. How Attachment Develops The first step in the development of attachment is learning to discriminate between familiar and unfamiliar people. In the second step, babies develop attachments to specific people. These attachments are revealed in the infants’ protests when attachment figures depart and their joyous greetings when they are reunited. Most infants develop their first attachment to their mother and rely on her for comfort. Later, infants develop attachments to their fathers and possibly with their grandparents and siblings. As children mature, they develop new attachment relationships with peers and romantic partners. Adolescent attachment relationships coexist with the attachments already formed to parents and siblings. The Nature and Quality of Attachment Early attachments are different in quality from one relationship to another and from one child to the next. The quality of an infant’s attachment can be assessed using observations of mother and infant at home. Ainsworth developed a laboratory assessment called the Strange Situation in which the child’s interactions with the mother are observed after the two have been briefly separated and reunited. Typically, 60 to 65 percent of infants are classified as securely attached to their mothers in the Strange Situation: They seek contact with her after the stress of her departure and are quickly comforted even if they were initially quite upset. Securely attached infants are confident in their mother’s availability and responsiveness. They use the mother as a secure base, venturing away to explore the unfamiliar environment and returning to her as a haven of safety from time to time. Insecure-avoidant infants show little distress over the mother’s absence in the Strange Situation and actively avoid her on her return. Insecure-ambivalent children may become extremely upset when the mother leaves them in the Strange Situation but are ambivalent to her when she returns; they seek contact with her and then angrily push her away. Insecure-disorganized infants act disorganized and disoriented when they are reunited with their mothers in the Strange Situation; they are unable to cope with distress in a consistent and organized way even though their mother is available. When parents are available, sensitive, and responsive to their infant’s needs and the two interact in a synchronous way, the child is more likely to develop a secure attachment. Contextual factors in the family and community are also related to attachment. Infants reared in socially impoverished environments may have hormonal deficits that alter their social responsiveness and lead to attachment problems. A baby’s temperament may play a role in the quality of the infant-parent attachment but only in combination with the caregiver’s behavior. Stability and Consequences of Attachment The quality of attachment is relatively stable across time but may change if the environment improves or deteriorates. Early attachments shape a child’s later attitudes and behaviors. Children who were securely attached as infants are more likely to be intellectually curious and eager to explore, have good relationships with peers and others, and view themselves positively. Children’s internal working models provide a mediating mechanism that serves as a link between attachment and later outcomes. Parents’ internal working models of experience with their parents are likely to influence their parenting behavior and their infant’s attachment. Mothers and fathers classified as autonomous, dismissing, and preoccupied according to the Adult Attachment Interview (AAI) are likely to have infants who are secure, avoidant, and ambivalent, respectively. Insecurely attached infants are more likely to become secure than the reverse. Support has been found for two explanations of attachment stability: The “mediating experiences” view suggests that continuity across time may be due to the stability of parents’ behavior and environmental conditions rather than the nature of earlier attachment patterns. The “dynamic interaction process” view suggests that children’s attachment histories modify how they perceive and react to changes in their family environment. Student Handout 4-2 Key Terms GLOSSARY TERMS attachment A strong emotional bond that forms between infant and caregiver in the second half of the child’s first year. imprinting The process by which birds and other infrahuman animals develop a preference for the person or object to which they are first exposed during a brief, critical period after birth. insecure-ambivalent attachment Babies tend to become very upset at the departure of their mothers and exhibit inconsistent behavior on the mother’s return, sometimes seeking contact, sometimes pushing their mothers away. (This is sometimes referred to as insecure-resistant or anxiousambivalent attachment.) insecure-avoidant attachment Babies seem not to be bothered by their mother’s brief absences but specifically avoid her when she returns, sometimes becoming visibly upset. insecure-disorganized attachment Babies seem disorganized and disoriented when reunited with their mother after separation. internal working model A person’s mental representation of himself or herself as a child, his or her parents, and the nature of his or her interaction with the parents as he or she reconstructs and interprets that interaction. maternal bond Feeling of attachment or bond by a mother to her infant, perhaps influenced by early postnatal contact. secure attachment Babies are able to explore novel environments, are minimally disturbed by brief separations from their parents, and are quickly comforted by their parents when they return. secure base A safety zone that the infant can retreat to for comfort and reassurance when stressed or frightened while exploring the environment. separation distress or protest An infant’s distress reaction to being separated from the attachment object, usually the mother, which typically peaks at about 15 months of age. Strange Situation A research scenario in which parent and child are separated and reunited so that investigators can assess the nature and quality of the parentinfant attachment relationship. OTHER IMPORTANT TERMS IN THIS CHAPTER Adult Attachment Interview (AAI) Attachment Q-Set autonomous attachment California Attachment Procedure (CAP) dismissing attachment dynamic interaction process model of attachment earned secure attachment extreme early effects model of attachment goal-corrected partnership interactive synchrony mediating experiences model of attachment narrative story method oxytocin parental insightfulness preoccupied attachment relationship representation secondary drive security object Student Handout 4-3 Adult Attachment and Close Relationships 1. How is attachment style as defined by anxiety and avoidance similar or different from assessment of attachment style in childhood in either the Strange Situation or one of the other methods discussed in the chapter? 2. Do you think that your attachment classification is related to the attachment you had in infancy and childhood? Why or why not? Cite evidence and theory as discussed in your text. 3. What does research and theory say about your attachment classification and relationships? 4. In what ways do you think your attachment classification might influence your parenting behaviors? 5. Do you think attachment styles are transmitted across generations? Why or why not? Practice Exam Questions CHAPTER 4. ATTACHMENT: LEARNING TO LOVE SAMPLE MULTIPLE CHOICE QUESTIONS 1. The central point of Harlow’s experiments with “surrogate mothers” was that: (a) attachment occurs in primates as well as humans (b) attachment is intrinsically tied to the feeding of the infant (c) attachment is not limited to one “caregiver” (d) *none of the above 2. Birds and other infrahuman animals develop a preference for the person or object to which they are first exposed during a brief, critical period after birth. This is referred to as: (a) attachment (b) secure base (c) object permanence (d) *imprinting 3. Unique contributions of Bowlby’s theory include: (a) the active role played by the infant’s smiling and crying (b) emphasis on the development of mutual attachments (c) the position that attachment is a relationship not a behavior (d) *all of the above 4. The phase of attachment that is characterized by children understanding parents’ needs: (a) *goal-corrected partnership (b) attachment in the making (c) clear-cut attachment (d) preattachment 5. Babies who are able to explore novel environments, are minimally disturbed by brief separations from their parents, and are quickly comforted by their parents when they return have a: (a) parental bond (b) secure base (c) *secure attachment (d) positive attachment 6. 39. Reasons the Strange Situation reveals cultural differences in the proportion of children exhibiting a secure attachment include the following: (a) *the degree to which the Strange Situation stresses infants varies across cultures (b) the degree to which attachment exists varies across cultures (c) the definition of a secure attachment varies across cultures (d) all of the above 7. Over 80 percent of abused children form _______ to their caregiver(s): (a) an insecure-avoidant attachment (b) an insecure-ambivalent attachment (c) *an insecure-disorganized attachment (d) a secure attachment 8. If you were observing institutionalized young children living in poor quality orphanages, about how many would you expect to be securely attached? (a) more than 85 percent (b) more than 65 percent (c) more than 55 percent (d) *none of the above 9. People’s mental representations of themselves in childhood, their parents, and the nature of their interactions with their parents are referred to as: (a) intergenerational representation (b) *an internal working model (c) both a and b (d) neither a nor b 10. Individuals who are able to overcome their early insecure attachments and develop secure relationships with their spouses and offspring are referred to as: (a) recovered secure (b) delayed secure (c) *earned secure (d) rediscovered secure 11. Researchers have found that at age 19 adolescents with a history of secure attachments are more likely to have: (a) *long-term friendships (b) higher-paying jobs (c) more early adulthood depression (d) children of their own 12. Rank the types of attachment relationships observed among U.S. infants from most frequent to least frequent: (a) secure, ambivalent, avoidant (b) *secure, avoidant, ambivalent (c) ambivalent, secure, avoidant (d) avoidant, secure, ambivalent ESSAY QUESTIONS 1. Attachment is best viewed as a dyadic construct. Discuss. 2. Attachment is a universal process but there are differences in the distribution of attachment types across cultures. Why? 3. What role does the feeding situation play in attachment development according to psychoanalytic theory, learning theory, and ethological theory?