Language-Dialect Pro.. - Michigan State University

advertisement

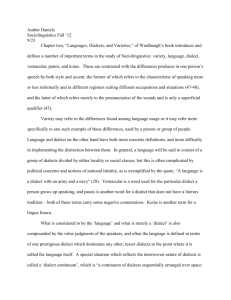

The Language/dialect Problem David J. Dwyer, Dept. of Anthropology, Michigan State University Abstract The question of what distinguishes a language from a dialect is examined by comparing current definitions (popular, linguistic and political) against actual usage. Each of these definitions are shown to be lacking in part due to an implicit acceptance of the opposition as a natural phenomenon. A new definition recognizing the opposition as a social construct is offered. Examples of the colonial imposition of this opposition on Shona and Tsonga demonstrate the potency of this Eurocentric concept. 1. Background Constructionism (Burger and Luckmann 1966) holds that some types of phenomena represent human inventions or creations as opposed to naturally occurring phenomena. The problem that constructionism poses, is not so much one of being unaware that some of our world is constructed and that some of it is natural, but rather one of separating the two. The danger in accepting constructed phenomena as natural is that we take them to be objective (independent of our own being), and unproblematic. The question of constructionism is of more concern in the study of social as opposed to physical phenomena. Furthermore, it would seem reasonable to expect this kind of thing to happen in areas of human social activity: theological positions, political disputes, literary analysis and perhaps even economics. But at first blush, it would seem unlikely that linguistic analysis could also be involved. Yet, this is precisely what this paper is about, that the distinction between language and dialect are not natural categories but are human constructs. In this particular case, I claim that the existence and use of writing was one of the main factors that has shaped this European view of language and dialect. One of the consequences of this Eurocentric view was that in the process of the colonialization of Africa, African linguistic, political and ethnic actualities were characterized to conform with European ideas. 2. The Problem The linguist is often asked: "What is the difference between a language and a dialect?” In formulating the answer, the linguist wants to make sure that non-linguists are disabused of the following popular claims made about the term dialect: 1) Dialects are structurally inferior to languages, lacking formal grammatical rules and standards of speaking; Dwyer: The Language-Dialect Problem 8/21/2002 page 2 2) Dialects are communicatively inferior to languages, lacking the full range of expressibility found in languages; 3) Dialects are orthographically1 inferior to languages, lacking their own system of writing. In short, dialects are inferior to languages. These claims lead the popular conclusion that languages are varieties of communication used by Westerners and by a few exceptional Non-westerners such as the Japanese, Chinese, Arabs and Ethiopians, while dialects are mainly used by Non-westerners and intellectually backward Westerners, particularly those found in isolated, rural communities. 2.1 Grammatical Inferiority. Linguists object to this point of view because they are aware that the study of the formal properties of the world's languages reveals no formal distinction between Western and Non-western languages with respect to the first point. In fact, the study of linguistics rests on the assumption that because of the nature of the human mind, all languages share a number of common properties called linguistic universals. Furthermore, much of what is done in linguistic research is to investigate individual languages to see how these linguistic universals play out in them. This approach has proven to be extremely successful, enabling all languages to be examined within the same framework. We see that all languages share the same semiological systems (phonology, lexicon and syntax) and within each system, that all languages share the same types of properties. $ Within phonology, all languages draw from the same potential set of phonological contrasts, known as distinctive features (such as: consonant/vowel; voiced/voiceless, stop/fricative, etc.). These distinctive features combine to form segments, syllables and phonological phrases. Each language draws from this universal potential to form a set of contrastive signs called phonemes. The nature of the patterning of these phonological entities can be characterized in terms of phonological rules stated in terms of these distinctive features. 1) Within the lexicon, words consist of smaller units called morphemes and that morphemes are represented by strings of phonological signs, called phonemes. 2) Within syntax, we find a basic set of syntactic categories (such as: sentence, verb phrase, noun phrase, noun, verb, relative clause, etc.) even though each language differs in the way that it handles these categories. For example, all languages have sentences composed of a noun phrase and a verb phrase, though they may differ in the order that they are presented. Much of the study of syntax has to do with discovering how the grammatical structures of individual languages reflect the Dwyer: The Language-Dialect Problem 8/21/2002 page 3 universal grammar. Because of these common and universal features of human language, linguists find that the claim that some languages are structurally inferior is fundamentally wrong and totally opposed to the empirical findings of their field. 2.2 Expressibility. In addition, while linguists do find that all languages encounter some difficulties in expressing certain notions, this is a far cry from saying that some concepts are fundamentally inexpressible in some languages. In fact, linguists frequently encounter non-western languages that have developed grammatical and lexical devices that enable the straightforward presentation of notions of considerable complexity, at least from the Western perspective. Benjamin Lee Whorf pointed out many such differences in which Non-western languages were vastly superior to Western ones. When comparing the devices for reporting information, Whorf (1956) remarked that “Hopi, when compared to English, is like that of a rapier compared to a bludgeon.” I argue below that the suffix -kan in Bambara represents the phenomenon of language variation more suitably than the English terms language and dialect. Consequently, linguists find that the second claim of communicative inferiority is equally wrong and opposed to the fundamental principles and empirical evidence that linguists have encountered. As far as linguists are concerned, there are no clear-cut or substantial differences in structural composition or communicative capacity between languages, let alone between Western and non-western languages. Furthermore linguists object to such claims, not only because of their wrongness but because they have the potential to serve the ideological claims of Western intellectual superiority. 2.3 Writing. Linguists do not find the third claim as objectionable, especially when it is rephrased as: 3'. Western languages tend to have writing systems while Non-western languages often do not. More importantly, however, linguists do not see the literate/non-literate distinction to be a fundamental one in the analysis of language structure. After all, the users of any language can develop a workable writing system without too much difficulty or too much investment in time. We are reminded, for example, of the Cameroonian leader Njoya who developed Dwyer: The Language-Dialect Problem 8/21/2002 page 4 a writing system almost overnight and immediately put together a five-volume book on the history of his Bamoun people (Ndam Njoya 1977). Here in North America, we find the example of the Cherokee who, following the development of a writing system, began publishing a newspaper and books of literary and practical merit. A second reason linguists give for de-emphasizing the importance of writing is that for all of us, language use is primarily oral, even for those of us who use a writing system, and that in all cases the written form of the language is derived from the spoken form. Thus, linguists do not find the claim of the lack of a writing system to be of any great import. While it may be argued that the presence of writing, like any technology, can have an effect on a given society (cf. Goody 1968, 1987 and Street 1984 and 1993), writing does not lead to a structural superiority of any sort. 3. The linguistic distinction between languages and dialect. Having seen in the preceding sections that linguists object to the popular characterization of the difference between language and dialect, we now ask to how the linguist seeks to characterize this difference? Bearing in mind, that there is some variability in the way linguists define their subject matter, let us proceed with the following widely accepted characterization. 3.1 The Linguistic definition. Beginning with the term idiolect, which is the way an individual speaks, particularity the structural aspects (the phonology, lexicon and syntax) of this speech, a dialect can be said to consist of a set of very similar idiolects admitting to only minor variations. From this perspective, a language can be said to consist of the set of mutually intelligible dialects. Two dialects are said to be mutually intelligible when a speaker of different dialects can understand each other without too much difficulty. Thus while British and American English, or Northern and Southern American English, or African-American and European-American English exhibit modest structural differences, these differences are not so great that they prevent mutual intelligibility and consequently they would characterized as having dialectal, rather than language, differences. However, using this criterion, we would have to conclude that, prior to the Norman invasion of 1066 when they were mutually intelligible, English and Norwegian Dwyer: The Language-Dialect Problem 8/21/2002 page 5 were dialects of the same language, even though today they represent different languages. Linguists go on to add that even though one of the dialects of a given language may be chosen as the literary dialect (the one in which written texts are generated), that fact in no way elevates that dialect as structurally or communicatively superior in the sense described above. The linguistic view of the language/dialect distinction has the advantage over the popular view in that it unambiguously denies the claim that Western languages are superior to non-western ones. 3.2 The Problem with the linguistic definition. Yet, while the linguistic definition has overcome its Eurocentric bias, it doesn't work. That is, when the definition is applied rigorously, it fails to explain why the linguistic entities like German, Igbo, and Chinese are termed languages and why mutually intelligible "dialects" like Swedish and Norwegian are considered different languages. For example, last summer I had the opportunity to observe a Norwegian and a Swede conversing easily on the topic of what each was doing in my house. Each spoke in her own language and each had little difficulty in understanding the other. Since we accept the fact that Swedish and Norwegian are mutually intelligible, they would be considered dialects of the same language using the linguistic definition. Likewise, a Spanish friend of mine, whom I met in graduate school and who now represents an American company in Europe, noted that when he travels to Italy for a meeting, he uses no translator; he speaks Spanish to his clients and his clients speak Italian to him. This is, I am told, a common practice. Admittedly, it may take a bit of time for one to "catch on" to the other "dialect," the same can be said for some "dialects" of English, but nevertheless, using the linguistic definition, Italian and Spanish would have to be considered dialects of the same language. In addition, the linguistic criterion of mutual intelligibility would exclude certain dialects traditionally associated with a particular language. For example, the German “dialects” of Switzerland are not mutually intelligible with those of northern Germany and in some cases, not even with other German "dialects" found elsewhere in Switzerland. The linguistic definition states that these varieties can not both be dialects of German, but must belong to separate languages. Dwyer: The Language-Dialect Problem 8/21/2002 page 6 A third weakness in the linguistic definition is one of indeterminacy; that is, it encounters many situations where a given dialect could be assigned to either of two languages. For example, standard German and standard Dutch are not mutually intelligible, but between Amsterdam to Berlin, one finds mutual intelligibility from one town to the next all along the way. Thus, using the criterion of mutual intelligibility, one could assign border dialects to either language. Thus, the linguistic definition clashes with our popular characterizations Norwegian and Swedish as separate languages and German as a single language. It also formally fails to resolve boundary problems as in the Dutch-German situation. 4. The Political distinction between language and dialect. The problems of the linguistic definition have led many linguists, half seriously, to propose that a language is a dialect with an army and a navy, i.e., a government. After all, Norway and Sweden have different governments today, as do Spain and Italy and the Netherlands and Germany. In fact, this distinction could be used to exclude Catalan, a Romance “language” spoken in the Barcelona area of Spain because it is not backed up by a government. Ironically, then, we discover that this capricious characterization of language and dialect seems to characterize these situations more successfully than the linguistic one. In fact, we can even extend this distinction to situations of mutually unintelligible "dialects." While we tend to think of Chinese as a single idiom accessible to all Chinese, many of the so-called dialects of Chinese are not even close to being mutually intelligible. Igbo is spoken by over 3 million people in eastern Nigeria. Yet, here, too, not all dialects of Igbo are mutually intelligible. Some people claim that not all dialects of English are mutually intelligible. When National Public Television presented a 15 part series on The Story of English many of the English "dialects" presented were subtitled because they were not clearly mutually intelligible to all viewers. Even though the dialects of Chinese are not mutually intelligible, they are under one government, at least according to the Peoples Republic of China. The same could be said for Igbo, which was the language of Biafra when it attempted to secede from Nigeria during the Nigerian civil war though in reality the characterization of Igbo as a single language is a colonial formation. In addition, the rather arbitrary division between Dwyer: The Language-Dialect Problem 8/21/2002 page 7 Dutch and German is explained by the presence of a political border. Those in the Netherlands speak Dutch, and those in Germany speak German. The political distinction has the advantage of overcoming the problems of mutual intelligibility and arbitrariness encountered by the linguistic distinction, yet this distinction too is flawed. We note that China has two governments (Mainland China and Taiwan), German has three (Germany, Austria, Switzerland) and English has at least six (the U.K., Ireland, Canada, Australia, New Zealand and the U.S. Finally, Arabic is the official language of over 15 countries. There are also a number of governments that recognize the legitimacy of more than one language within its borders: Belgium, Switzerland, Canada, and a good number of African countries. However, we also encounter languages without any governmental connection. A Mende-speaking friend of mine in Sierra Leone asked me about my field research, which was to compare the historical development of the Southwestern Mande languages of Sierra Leone and Liberia. These languages include, in addition to Mende and Loko of Sierra Leone, Bandi, Lorma and Kpelle of Liberia and are about as closely related as the Romance languages, which include: French; Spanish; Italian among others. My friend informed me that he could understand the news broadcasts from Liberia which were in Bandi. By the linguistic definition, Mende and Bandi would be dialects; by the political definition, they are anomalous for neither has a government. The official language of Sierra Leone and Liberia is English. Throughout the world, minority (and sometimes majority) languages exist without formal recognition, and would therefore by the political distinction because they lack this governmental connection, be considered dialects. 4.1 The Naturalness of the Language/Dialect Distinction. At this point, we seem to have encountered a dead end, for no current distinction seems to work. The popular distinction fails empirically and in its Eurocentricity. The linguistic distinction fails empirically, and the political distinction, while appealing in some respects, fails empirically as well. This conundrum leads us to suspect that the problem is not the definition, but the distinction between language and dialect is not a natural one but a social construct. As such, the distinction between language and dialect is not a universal category, Dwyer: The Language-Dialect Problem 8/21/2002 page 8 and so one would expect to find other ways of characterizing language variation. Bamanankan, the most widely spoken language of the Republic of Mali, has no lexical distinction between language and dialect. However, it does have a productive suffix kan that means something like ‘manner of speaking of’. Thus, Bamana-kan means ‘the manner of speaking of the Bamana (also known as the Bambara)’ which would translate into 'the language of the Bamana’. Likewise, Hausakan would translate as ‘the Hausa language.’ But one also finds the word Bamakakan meaning ‘the manner of speaking in Bamako (the capital of Mali)’. In this case, we would translate the word as ‘the dialect of Bamana spoken in Bamako.’ Finally, Abdulakan would translate as the ‘idiolect of Abdula’. Here we find a situation where the distinction between language and dialect is not only not made, but apparently not needed. Interestingly, many linguists are now using the term (language) variety to refer to a way of speaking without having to characterize the type as either a language or a dialect. This lack of distinction between language and dialect may help to explain a situation I encountered in Cameroon as a Peace Corps Volunteer (Dwyer 1993). While working in the town of Jotin on a community development project, I was asked to carry out a language survey. No sooner had I started than things began to get confusing. One of my first questions to a Jotin farmer was "what language do you speak?” Actually my question was in Cameroon Pidgin English, the lingua franca of the area and was phrased as follows: Huskayn tok yu detok? What language you continually speak? The answer I received was an "I don't know." I of course was dumfounded. How could you not know what language you spoke? At the time, I simply gave up, but in retrospect, perhaps the Bambara distinction will help clarify things. The farmer obviously knew he spoke language; the question was what kind. If the farmer had a notion of language something like the Bambara suffix -kan, then the question would turn out to be incomprehensible: "What manner of speaking do you speak? If this were the question, then no wonder it appeared perplexing. The answer might have been something like: "I speak in the manner of Jotin." But that was so Dwyer: The Language-Dialect Problem 8/21/2002 page 9 obvious no intelligent person would even bother to ask. Yet, the question was being asked by a foreigner, and some measure of politeness was in order. Hence the answer: "I don't know."2 Both of these examples bring out the point that the distinction between language and dialect is not a natural phenomenon as Westerners assume. We see from these African examples that the distinction is unnecessary. Bambara allows for the characterization of degrees of differences of the way people speak without drawing a sharp line between language and dialect. For example, it is possible to say in Bambara that the difference between Bamakakan and Segukan is not as great as between Bamakakan and Hausakan without having to resort to the pidgin-holing categories of language and dialect. If this is so, then why have Europeans developed a distinction between language and dialect? 5. A literary distinction between language and dialect. The languages of Bamanakan and Pidgin tell us that the language dialect distinction is not universal, and furthermore reminds us that it is a social construct. What is interesting about this distinction is that it tends to be found only in places where there is a literary tradition. As noted above, linguists have not found the distinction between literate and non-literate languages at all useful for this distinction has no influence, as stated above, on the complexity of the structure or on the communicability of the language variety. However, this is not to say that the development of writing is without influence. Beginning with the work of Goody (1968, 1987) and followed by others including (Goody and Watt 1979) and Street (1984, 1993) the existence of a literary tradition has consequences for the society that adopts it. Accordingly, I suggest a literary basis for the language/dialect distinction. 5.1 The Literary definition. Specifically, I propose that the Eurocentric distinction between language and dialect arose in response to a situation imposed by the development of writing. One of the "consequences of literacy" was the development of two types of systems of communication. These came to be called in English "language" and "dialect" such that a language has a writing system while a dialect does not. As can be seen, this definition is a rephrasing of point two in section one above. In this rephrasing, however, I have avoided the claim of intellectual superiority for dialects with Dwyer: The Language-Dialect Problem 8/21/2002 page 10 writing systems without denying the benefits of writing. To elaborate, we can now offer a literary characterization of the distinction between a language and a dialect. Dwyer: The Language-Dialect Problem 8/21/2002 A language consists of a literary dialect, the variety used to represent the language in writing. Any variety which uses that literary variety for writing is also part of the language but its oral form is considered a dialect. Literary dialects, and hence languages are distinct when their orthographic traditions differ with respect to their alphabetic and lexical inventories, spelling conventions, word divisions and punctuation. -11- page 11 Dwyer: The Language-Dialect Problem 8/21/2002 page 12 Most importantly, this definition recognizes that the language/dialect distinction is a social construct and not a universal characterization. As such, it only applies in situations where a literary tradition is operative. It cannot be applied to situations where such a tradition has not taken root. In addition, it should be understood that the definition makes no claims to the superiority of the written tradition, but only that when such a tradition exists, the language/dialect distinction will conform to the definition. It should also be clear, that while the literary dialect is in many ways the most visible aspect of a language, the language also includes all the participating dialects. Thus, the variety of English that I speak is a dialect, but the variety that I write is a language. With this distinction we begin to see monolingual3 nations as consisting of a literate dialect (language) along with any number of spoken dialects. Furthermore, this definition resolves the paradoxes encountered by the other definitions. The German/Dutch continuum is easily accommodated, given that the Dutch dialects owe their allegiance to written Dutch and the German dialects owe theirs to written German. The fact that there are dialects of German in Switzerland does not challenge this view, as it would using the political definition because these dialects, too, owe their allegiance to written German. English as well, despite its six armies and navies has only one written system to which all dialects subscribe. By this definition, the African languages of Chewa, spoken in Zambia, and Nyanja, spoken in Malawi (despite their mutually intelligibility), are thus recognized as different languages, not because of separate armies and navies, but because of slightly different orthographies. Likewise, the virtually identical languages of Serbian and Croatian stand as distinct by virtue of their differing orthographies, and not because of their recently developed armies. Another such example is that of Romanian and Moldavan. These two Romance "languages” are virtually identical and clearly mutually intelligible. But while Romania is an independent country, Moldavia is part of Russia. To emphasize this difference, Moldavan is written in the Cyrillic alphabet, the same one used for Russian while Romanian is written with a roman alphabet. Dwyer: The Language-Dialect Problem 8/21/2002 page 13 Under this definition, Norwegian and Swedish are different languages because they have different writing systems. Norwegian, and Japanese represent an interesting situation for they have multiple orthographies, but this fact does not jeopardize this definition for all dialects of Norwegian owe their allegiance to both writing systems and all Japanese dialects to its three writing systems. Chinese provides one of the most interesting tests of this distinction, for Chinese is one of the few languages in the world using a logographic writing system. Logographic writing systems differ from phonological writing system in that symbols are used to represent words as opposed to representing sound, whether syllables or individual sound segments as is shown in the following table. Writing Type Logographic Syllabic Consonantal Alphabetic Principle 1 symbol per word 1 symbol per syllable 1 symbol per consonant 1 symbol per segment Languages Chinese, Mayan Japanese, Cherokee, Amharic Arabic, Hindi, Hebrew English Example 2x3=6 I.O.U, X-mass no example Greek and Greek imitators two times three Logographic, syllabic and alphabetic modes. .To get some idea of how logographic symbols work, one has only to look at the international icons, graphic road signs or for that matter the Arabic numbering system. The logographic symbol "5" stands for a word (or a concept) and not a sound. This fact makes it possible for extremely different languages, English (five), French (cinq), Mende (loolu), etc. to use the same symbols, for they attach to lexical signs (words) and not to the sounds of the language at the representational level. In fact, this is the important point about Chinese. Because the Chinese writing system does not depend on sound representation, varieties that are vastly different and nowhere near mutual intelligibility, can owe their allegiance to the same writing system. Thus, it can be maintained that despite the disparity of Chinese varieties of speaking, they can still be considered dialects of the same language. 5.2 Consequences of the Literary Distinction. The construction of the language/dialect distinction is not without its consequences. For example, associated with literary Dwyer: The Language-Dialect Problem 8/21/2002 page 14 dialects is an expectation of invariance. That is, the standard literary dialect, particularly when written, admits to very little variation, in areas of syntactic usage, word usage and spelling. While it is true that the literary dialect does admit to some variation in spelling, particularity in proper names, this is very different from the variations that are found in spoken language, even in the spoken versions of the literary dialect. I suspect that the reason for this invariance has less to do with making a text easier to read than with the status of the literary dialect. That is, the lack of variance in the literary dialect allows for a distinction between language and dialect to be viewed as one between proper and deviant forms. Consequently, when one finds variation in the speech of others it is perceived as ungrammatical, inelegant and unsophisticated rather than simply an alternative form of self-expression. This notion of deviance leads to the potential for exclusion and devaluation of those who do not use the literary dialect. Once a literary dialect is established, speakers of nonliterary dialects may come to see the literary dialect as the mechanism of their social oppression leading them to eschew not only the literary dialect, but access to writing (Freire and Macedo 1987). This may even lead such people to see themselves as linguistically and socially deviant or even inferior to users of the written dialect. Thus, while there can be no question about the advantages that the literary dialect offers to its users, there can also be no denying that its existence poses serious problems to a society with egalitarian aspirations. 6. The political distinction revisited. While the revised literary definition seems to capture the semantics of the language/dialect distinction more precisely than the political definition, it is nevertheless worthwhile asking why the political definition, despite its failure to cover all situations, does seem to characterize a good number of situations quite well. What then is the connection between the literary definition and the political one? Dwyer: The Language-Dialect Problem 8/21/2002 page 15 6.1 Monolingual Policy. Given that a state is a political entity charged with managing the affairs of its citizens, it follows that among other things, a state is charged with dealing with regulating education, political elections and mass communications, all of which contain a dimension of language (using the literary definition) use. Consequently, a state will be involved in decisions about language policy, whether they are consciously articulated or not. A state must decide in what language(s) to educate its citizens, in what languages to carry out the affairs of government, political deliberations, the judicial process, mass communication, etc. And because of practical difficulties associated with a multilingual language policy (cost of duplication, efficiency, and national unity), a monolingual policy turns out in most cases to be the most practical one. The existence of numerous multilingual countries in the world indicate that a monolingual policy is not inevitable. Frequently multilingual states have two or more sizable populations for which each population sees a specific language as essential to its identity and is reluctant to abandon both the language and group identity in favor of a nation-wide identity and language. 6.2 Nations. We take the term nation to refer to a state that has a common culture, language and tradition.4 In nations, we expect to find that the name of the state and the name of the language are etymologically related (e.g., Germany, German; France, French; Spain, Spanish). Almost every Western nation has minority populations speaking languages other than the official language, a fact that indicates that the monolingual policy has been imposed rather than a situation that has evolved on its own. Some countries like Belgium, Switzerland, Canada recognize two or more official languages. Other countries contain significant populations where unofficial languages are spoken. In France, one finds Basque in the south and Breton in the north being spoken as a first language by sizable groups. In Spain, one finds Basque to the west and Catalan to the east. In the United States, Spanish is spoken by at least 20% of the population. In many of these countries where minority languages are not officially recognized, there is an effort for greater recognition and often for political autonomy that Dwyer: The Language-Dialect Problem 8/21/2002 page 16 is often opposed by the government. In France and Spain, for example, the Basque language was completely ignored in favor of using a unifying monolingual language policy. In both France and Spain, the Basque feel that they have been overlooked culturally, politically and economically. This has led to a Basque movement for political autonomy. One of the major arguments for legitimizing autonomy is that just cited: because Basque is a language distinct from French and Spanish, it stands for a unique ethnicity, culture, in short, a nation. Consequently, as a nation, the Basque speakers have the right to form an independent state. Also in Spain, where Catalan (spoken in the Barcelona area) is mutually intelligible with Castilian Spanish, and for that matter with the spoken French just over the French border, similar arguments have been advanced for political autonomy. Because Catalan is mutually intelligible with Spanish it can, using the linguistic definition, be considered a dialect of Spanish. Without an argument for being a distinct language, the case for being a distinct nation and its demands for political autonomy are considerably weaker. However, if the literary definition between language and dialect is used, Catalan can show itself to be an independent language by establishing a distinct orthographic tradition. This has been done. Today, one finds "bilingual" signs in Barcelona proclaiming the independence of Catalan as a language and along with it, the right of its speakers to political autonomy. It is thus quite common, as illustrated by the Catalan situation, that the debate for political autonomy plays itself out at the level of the legitimacy of an orthographic tradition. 7. The Eurocentric framework. What is important in this struggle for and against autonomy by groups within a state is that the language/dialect question is seen by the players as part of the natural order and not a social construct. Thus, the issue in the struggle is not the reality of the distinction, for that is taken for granted, but whether the claim of language status by the local group conforms to that (constructed) reality. That is, if the local group can be shown to possess a language distinct from the official state language, then it can make Dwyer: The Language-Dialect Problem 8/21/2002 page 17 a claim that it deserves to be a nation and has a right to self-determination. Whether or not the local-group succeeds in this enterprise, the language/dialect distinction is sustained. This paper has argued for the perspective that the language/dialect distinction has arisen as a human construction and not, as is sometimes believed, a natural phenomenon. To further illustrate this point, I draw on a body of growing literature being developed by historians in their study of the colonial period of southern Africa. Both of these cases involve the imposition of the Eurocentric Language-Nation framework on an African situation by European colonizers and missionaries as they went about their business. What is remarkable about both of these examples, which I term "the crystallization of Shona" and the "invention of Tsonga" is that while many of the European participants were aware of the discrepancies between their framework and the empirical facts, this did not deter them in the least. Lest this paper be taken as a diatribe against missionaries, colonials or Europeans, let it be said, that these examples merely illustrate the general human capacity to overlook imperfections in one's own constructs, especially when one possesses substantial power over others in the pursuit of one's own interests. 7.1 The Crystallization of Shona. The information presented in this section draws extensively from the work of Chimhundu (1992). To begin with, the varieties encompassed by what is now called Shona do appear to represent some sort of linguistic entity distinct from other neighboring varieties such as Ndebele, even though until 1931 there was no consensus as to what to call it or how it was internally constituted. Even more importantly, the area had never been a political entity in the sense that there was a state which embraced all and only Shona speakers. To be sure, at one time or another, there were states that embraced some of this area, but such states usually embraced non-Shona speaking areas as well. More typically, the area was composed of autonomous, self-governing communities without an over arching state apparatus. In other words, the current Shona-speaking area has never constituted a nation in the sense that we have been discussing the term. Dwyer: The Language-Dialect Problem 8/21/2002 page 18 Most discussions of the dialects of Shona refer to the work of Doke (1931) who conducted a very intensive survey of the Shona-speaking area. Doke presented his findings about the nature of the dialectal variation by positing six different “dialect groups”: Korekore, Zezuru, Manyika, Ndau, Karanga and Kalanga. This mapping (figure 1) was intended to impose order on the considerable variation within Shona. Yet, a map showing such boundaries exaggerates both the differences between neighboring dialects divided by such boundaries and the internal cohesion within such boundaries. Today, these dialect groups are understood to be dialects admitting to little internal variation. In the early part of the 19th century, a number of Christian Missions settled in the Shona-speaking area. Each of these denominations set about establishing a literary dialect for the purposes of making religious literature available to their potential converts. Partly because these missions worked in different dialectal areas, but more importantly because these missionaries had little linguistic sophistication and because the process often involved using interpreters who were not fully proficient in Shona or in English, variants of written Shona evolved in each of the missions. Because of differences in the choice in letters to mark phonological contrast, spelling conventions, word division and word choices, these literary forms suggested that there was far greater diversity within Shona than actually existed. Yet, there was an awareness by these mission groups, that underneath the differences exhibited by various mission orthographies, there was the potential and interest to develop a unified orthography for the whole of the Shona-speaking area. This lead to the establishment of the Southern Rhodesian Missionary Conference (1903-1928). However due to the parochial interests of each of the missions they were never able to resolve this issue, finally declaring: Dwyer: The Language-Dialect Problem 8/21/2002 page 19 This Conference finds itself unable to decide at present between the alternatives of standardizing the two languages of Mashonaland, viz. Chizezuru and Chikaranga, or standardizing a unified language on the four existing [i.e., represented] dialects. We therefore prefer to reserve our opinion until expert advice has been obtained (Doke, C. Report on the Reunification of the Shona Dialects. 1931:5) As a result, Clement Doke, a linguist at the University of Christian Missions in the Shona-speaking area Language Variety Korekore Zezuru Missions Within Area None Roman Catholic Church Manyika Karanga Roman Catholic Church Anglican Church Methodist (United) American Board Mission (American Methodist) Dutch Reformed Church Kalanga Ndebele London Missionary Society London Missionary Society Witwatersrand, was called in to conduct a survey and make some recommendations. Ndau Working with Doke was an advisory committee Representation on Doke Commission None Rev A. Burbridge, Catholic Church Rev B.H. Barnes, Anglican Church Rev B.H. Barnes, Anglican Church Mrs. C.S. Louw, Dutch Reformed Church No Representative No Representative composed not all of the missions involved. From table II we see that the Korekore of representatives from some, but group and the Kalanga group were not represented and that same person represented Manyika and Ndau. Doke was charged with providing a "settlement of the language problems involving the unification of the dialects into a literary form for official and educational purposes, and the standardization of a uniform orthography of the area" Doke (1931:iii) Doke's report contains a number of recommendations, most of which have been adopted directly or with slight modification. 1) The commission recommended a unified orthography and that the name of the language be Shona. 2) In establishing the orthography, Doke based word divisions, not on the common semantically based practice of separating morphemes but on the phonological principle, common to many Bantu languages of penultimate stress. To represent a number of important phonemic contrasts, Doke resorted to specialized phonetic symbols that were later replaced by two letter combinations to render the system reproducible on a standard typewriter. 3) In choosing the vocabulary, this commission relied most heavily on Zezuru and to a lesser extent on Karanga. Manyika and Ndau were drawn on occasionally, and Korekore and Kalanga were completely ignored). Chimhundu points out that this merely reflected the degrees to which each dialect was represented on the Dwyer: The Language-Dialect Problem 8/21/2002 page 20 commission. 4) Finally, Kalanga, was reclassified as a dialect of Ndebele (another Bantu language) to which it is adjacent, despite the fact that it was recognized by Doke as being mutually intelligible with other varieties of Shona. This was made possible because of its geographical isolation from the other Shona varieties, but more importantly to the fact that it did not have a representative on the Doke commission and to the fact that like Ndebele, it was under the aegis of the London Missionary Society. 5) As a result of this mission activity and the subsequent Doke commission, Shona has been crystallized in the European mold as a single language with a common literary dialect and a common name. The literary form was constructed largely from the Zezuru, due to political as opposed to linguistic grounds. This construction took place without the any significant participation of the Shonaspeaking population. Furthermore, since its expulsion from Shona and reassignment to Ndebele, Kalanga is becoming less like Shona and more like Ndebele. Ethnologue (10th Edition, 1984:302), a publication reporting on the status of Bible translations in the world's languages, reports that Kalanga is "rapidly being absorbed by Ndebele, though most rural members speak Kalanga. Portions [of the Bible] in Kalanga need revision. The Shona revision will not serve." 7.2 The Invention of Tsonga. In this section, based largely on Harries (1987 and 1989), I argue that the language now known as Tsonga (currently spoken in the northern and eastern Transvaal, including the southern part of Mozambique), arose, not in the classical way of a splintering and independent linguistic development, but through the imposition of a Western perspective in the pursuit of Western interests. In the early 1900s before any substantial European influence, the area currently inhabited by Tsonga-speaking people (see map) could hardly be said to be either linguistically or culturally coherent. The earliest known inhabitants of the area were hunters and traders; they were followed in the 19th century by a series of immigrations triggered by political and ecological upheavals including Nguni refugees from the south and in the 1830s and the Gaza civil war refugees during the 1860s. Although most of the population spoke one Bantu language or another, it could Dwyer: The Language-Dialect Problem 8/21/2002 page 21 not be characterized as linguistically homogeneous. Politically the area was characterized by autonomous villages with a centralized authority, although for much of the 19th century, these communities fell under the political domination of three different political entities: the Gaza Nguni to the north; the Swazi to the west and the Zulu to the south. At no time did this area constitute a self-contained state with its own identity. In fact, what singled this area as an entity at all according to Harries was its foreignness to any other known group in the area. In fact, Harries points out that one of the terms for this area, ‘Tsonga’ is Zulu in origin meaning ‘conquered peoples in costal areas north of the Zulu, a term that carried pejorative overtones. Towards the end of the 19th century (1873), this area was assigned to the Swiss Missionary Society, with adjacent areas going to missionaries of other nationalities and denominations. Part of the strategy for allocating lands for missionary activities was to create culturally and linguistically coherent territories. As in the case of Shona, an important first step for the missionaries was to establish a written version of the local language in order to create religious texts. Given that there were several quite-different, Bantu-based varieties being spoken in the area, the task of producing a written language is portrayed by Harries as "compiling" (1989:87) a written language as opposed simply reducing the language to writing. Apparently, this system, which be came to be known as Gwamba,v was based on a gradually evolving lingua franca. But the construction of Gwamba by Henri Berthoud relied on a variety of this lingua franca spoken in the Delagoa Bay area, particularity as it was used by his evangelical assistants whose first language was Sotho. Berthoud's work gave rise to the publication of numerous religious texts and manuals during the 1880s. According to Harries, Berthoud had the view that Gwamba would unite the entire area under his mission, much like "Jacobine French, High German or Castilian Spanish had linked large numbers of people in Europe who shared, however distantly, a linguistic relationship" (1989:86) and thus would consolidate even more firmly the Swiss Missionary Society's claim to this area. Dwyer: The Language-Dialect Problem 8/21/2002 page 22 However, literary Gwamba created problems for the Swiss missionaries working in the Lorenzo Marques area where the newly- created Gwamba literature appeared more foreign than that used by the encroaching Wesleyan missionaries. In order to compete, Henri Junod, another Swiss missionary, constructed another literary variant of this lingua franca, which he called Ronga. Despite protests from Berthoud who, as mentioned above, wanted a single literary form to unite the area. Nonetheless, through Junod's efforts, Ronga established itself as an independent entity in the eastern areas. Subsequently, Gwamba was relabeled as Thonga by Junod and Shangaan by Berthoud. While Junod opposed Berthoud on the issue of Ronga, he nevertheless agreed that for the sake of the mission, the area should be seen as a homogeneous unit. Thus, Junod declared Thonga/Shangaan as the northern dialect, Ronga as the southern dialect and Tswa, a literary tradition cut from the same stock by American missionaries, as the western dialect. Harries notes that Junod then attempted to create a sense of nation for this area by constructing cultural artifacts to go along with these constructed dialectal differences. Despite Junod's unfamiliarity with much of the territory in question, he had no difficulty in ascribing cultural differences representative of each area including proverbs, folklore, and other customs. Today, this language, which is generally known as (Shi)tsonga, represents the language and literary tradition of the northern part of the area, with Ronga being that of the southern part. The orthographic and spelling conventions employed by each tradition are such that the similar nature of their origins is no longer obvious. For example, Ethnologue concludes that Ronga and Shitsonga are only "probably one language" (254). Thus the linguistic situation, which at the turn of the century could be characterized as a heterogeneous collection of individuals speaking a variety of (Bantu) languages, is now portrayed as a homogeneous ethno-linguistic area consisting three discrete dialects, one of which, due to its different orthographic tradition, has the appearance of a distinct language. In commenting on these developments, and in particular the efforts of Junod, Harries observes: Dwyer: The Language-Dialect Problem 8/21/2002 page 23 Because of his positivist approach, Junod, unlike Berthoud, failed to see that his linguistic and related social divisions were human constructs that were in no way scientifically objective. Unlike microbes or river moths, the Ronga and the Thonga/Shangaan languages were not awaiting discovery; they were very much the invention of European scholars and, perhaps even more so, of their African assistants. The linguistic borders determined by the Europeans conformed to a certain preconception of what they expected to find (Harries 1989:88). The example of Tsonga is even more remarkable than Shona, for not only were the literary forms of Tsonga and Ronga constructed by outsiders, but they had an effect on the shape of the oral language as well. In addition, once these entities were created, they were then reimposed on the area to give what was originally a heterogeneous area the appearance of a coherent linguistic area with discrete subdivisions, each of which possessed distinct, albeit related, cultural traditions. 8. Summary. This discussion of the language/dialect problem reveals an evolution in the thinking about how this relationship should be viewed. The definition offered by the field of linguistics sought to overcome the pejorative nature of the popular definition that claimed that some human varieties of speech known as languages, which were for the most part Western, were superior to others known as dialects, which were for the most part Non-western. To overcome this Eurocentric bias, the field of linguistics proposed an objective characterization of the language/dialect opposition as a natural phenomenon. This definition claimed, on the basis of an objectively available principle of mutual intelligibility, that the speech varieties of the world would reveal the natural clustering of linguistic varieties into discrete collections of mutually intelligible dialects not unlike the scientific classification of living things. Despite overcoming the Eurocentric bias of the popular definition, the linguistic definition failed on both formal and empirical grounds. Formally, the distinction failed because it encountered numerous indeterminate cases. For example, the definition Dwyer: The Language-Dialect Problem 8/21/2002 page 24 yielded situations where a given dialect could be assigned to either of two distinct languages, such as the case of varieties spoken on the German/Dutch border. Empirically, the linguistic definition contradicted numerous commonly accepted situations such as German and Chinese, which embraced mutually unintelligible dialects, as well as mutually intelligible languages such as Norwegian and Swedish, Spanish and Italian, and Chewa and Nyanja. The failure of the linguistic distinction gave rise to a politically based definition that characterized a language as the idiom of the nation. This definition overcomes the problems of indeterminacy inherent in the linguistic definition, such as the relationship between German and Dutch, Norwegian and Swedish and Chewa and Nyanja as well as the coherence of German and Chinese. In addition, the political definition represents a shift in perspective to one that claims that the language/dialect distinction is socially constructed and not a natural one. Unfortunately, the political distinction also is not without difficulties. First, there is the problem of multinational languages like English, German and Arabic, which are the national language of several states, and then there is the problem of subnational languages like Basque and Mende for which no state exists. The literary distinction arose in response to the political definition. While it too recognizes that the language/dialect distinction is a socially constructed one, it proposed that the basis of this distinction be the establishment of a writing system. Thus, a language consists of a dialect with a writing system (characters, word divisions and spellings) and a set of dialects that use the writing system. The literary definition overcomes the difficulties of the political definitions and conforms to our general understanding of what constitutes a language and its dialects including: German and Chinese with its mutually unintelligible dialects; the mutually intelligible languages of Norwegian and Swedish; transnational languages like English and Arabic and even stateless languages. In addition, by recognizing the state's preference for a single national writing system, we can see why the political definition worked fairly well. In recognizing that this distinction is socially constructed, the definition does not Dwyer: The Language-Dialect Problem 8/21/2002 page 25 need to claim that it encompasses all linguistic varieties, for where there is no writing, the definition does not apply. Bambara, like many African languages, for example, does not distinguish between language and dialect. In fact, as it becomes clear that the language/dialect problem is Eurocentric or at least likely to occur where there is a literary tradition. Yet as a social construction, there is the real possibility that this distinction is not an automatic outcome of situations where a literary distinction has been established. And while the literary distinction unambiguously declares itself to be constructed, and not a natural phenomenon, this does not prevent the language/dialect distinction from being viewed as a natural one so much so that it was exported from Europe and imposed on what we now call Shona and Tsonga. In examining the language/dialect problem, this paper has not only attempted to clarify the nature of this distinction, but to point out the distinction between natural and constructed phenomena and to heighten the awareness that whenever social phenomena are investigated, this question ought to remain open to empirical examination. REFERENCES Berger, Peter and Thomas Luckmann 1966 The Social Construction of Reality. Doubleday. Chimhundu, Herbert 1992 Early Missionaries and the ethnolinguistic factor during the ‘invention of tribalism’ in Zimbabwe. Journal of African History 33:87-109.) Doke, C. 1931 A Comparative Study of Shona Phonetics. Johannesburg. Dwyer, David 1993 Becoming an Anthropological Linguist. In Anthropologists and the Peace Corps: Case Studies in Career Preparation. Brian E. Schwimmer and D.Michael Warren editors. Iowa State University Press: Ames. Pp. 43-49. ISBN 0-8138-0493-0. Freire, Paulo and Donaldo Macedo 1987 Literacy: reading the word and the world. Bergin and Garvey: South Hadley, Mass. Goody, Jack. 1968 Literacy in Traditional Society. Cambridge U. Press. Dwyer: The Language-Dialect Problem 8/21/2002 page 26 1987 The Interface Between the Written and the Oral. Cambridge U. Press. Goody J. and Watt. 1979 The Consequences of Literacy." Language and Social Context. P. Giglioli (ed.). Middlesex, U.K.: Penguin Books. Pp. 311-357. Harries, P. 1987 The roots of ethnicity: discourse and the politics of language construction in South Africa. African Affairs 25-52. 1989 Exclusion, Classification and Internal Colonialism: The emergence of Ethnicity among the Tsonga. The Creation of Tribalism in Southern Africa. L. Vail (ed.). University of California Press. Ndam Njoya, Adamou 1977 Njoya: réformateur du royaume. Bamoun, Afrique biblio-club; Paris (9, rue du Château-d'Eau, 75010: Dakar; Abidjan: Nouvelles éditions africaines. Street, Brian. 1984 Literacy in Theory and Practice. Cambridge U. Press. 1993 Cross-Cultural Approaches to Literacy. Cambridge U. Press. Whorf. Benjamin Lee 1956 A linguistic consideration of thinking. Language, thought, and reality; selected writings (edited and with an introduction by John B. Carroll). M.I.T. Press. Pp. 6586. World Bible Translation Society 1984 Ethnologue (10th Edition). World Bible Translation Society. ENDNOTES Dwyer: The Language-Dialect Problem 8/21/2002 page 27 1.The term "orthography" refers to the system of writing used by a language. 2.There is another possible interpretation. That is, while my question was the correctly translated into Pidgin, the term tok does mean "language," but as can be seen from the example the word tok has a broader range of meaning. In fact, the word tok also means ‘discourse’ or ‘speech’. Thus the farmer could have translated my question as: "what sort of discourse do you engage in? This would appear to be a rather strange question to ask someone following a question about the size and health of his poultry flock. 3.In section 6, many apparently monolingual countries are shown to be multilingual. 4.Using this definition, it is clear that some states are more nation-like than others. v.The term ‘Gwamba’ itself has an interesting etymology being originally the name of a village head and subsequently a term for ‘easterner’.