9-23 critique Ch2 Warhaugh - Amber Daniels - apl623-f12

advertisement

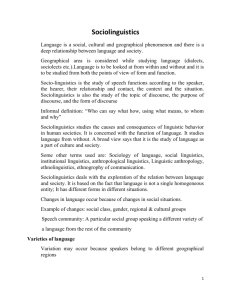

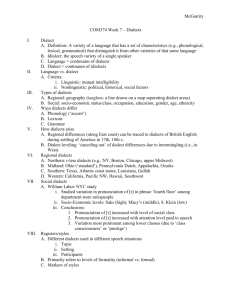

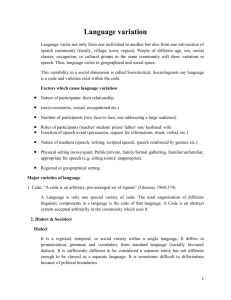

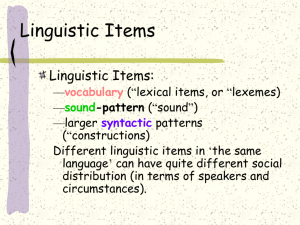

Amber Daniels Sociolinguistics Fall ‘12 9/23 Chapter two, “Languages, Dialects, and Varieties,” of Wardhaugh’s book introduces and defines a number of important terms in the study of Sociolinguistics: variety, language, dialect, vernacular, patois, and koine. These are contrasted with the differences produces in one person’s speech by both style and accent, the former of which refers to the characteristic of speaking more or less informally and in different registers suiting different occupations and situations (47-48), and the latter of which refers merely to the pronunciation of the sounds and is only a superficial qualifier (43). Variety may refer to the differences found among language usage or it may refer more specifically to one such example of these differences, used by a person or group of people. Language and dialect on the other hand have both more concrete definitions, and more difficulty in implementing the distinction between them. In general, a language will be said to consist of a group of dialects divided by either locality or social classes, but this is often complicated by political concerns and notions of national identity, as is exemplified by the quote, “A language is a dialect with an army and a navy” (28). Vernacular is a word used for the particular dialect a person grows up speaking, and patois is another word for a dialect that does not have a literary tradition – both of these terms carry some negative connotations. Koine is another term for a lingua franca. What is considered to be the ‘language’ and what is merely a ‘dialect’ is also compounded by the value judgments of the speakers, and often the language is defined in terms of one prestigious dialect which dominates any other, lesser dialects to the point where it is called the language itself. A special situation which reflects the interwoven nature of dialects is called a ‘dialect continuum’, which is “a continuum of dialects sequentially arranged over space: A, B, C, D, and so on. Over large distances the dialects at each end of the continuum may well be mutually unintelligible, and also some of the intermediate dialects may be unintelligible with one or both ends, or even with certain other intermediate ones. In such a distribution, which dialects can be classified together under one language, and how many such languages are there?” (42). Thus arises dialect geography, the name given to “attempts made to map the distributions of various linguistic features” (43), isoglosses of a particular feature, and dialect boundaries. Among attempts to authoritatively quantify the difference between languages is that of Bell’s seven criteria: standardization, vitality, historicity, autonomy, reduction, mixture, and de facto norms “(Bell, 1976, pp. 147-57)” (31). An important concept in this chapter is the influence of “ideological dimensions – social, cultural, and sometimes political – beyond…purely linguistic ones” (32). Frequent examples are made between small European countries with intelligible ‘languages’ and the unification of Chinese ‘dialects’ through one writing system, though they are mutually unintelligible. The concept of language as ideology is confluent with the concept of language as identity and thus impacts the politicizing of language teaching in schools. What is considered the ‘norm’ will of course be taught by preference in any particular social system, and a notion of ‘correct’ versus ‘incorrect’ is formed which motivates the adherents of prescriptivism, or an ‘us’ versus ‘them’ mentality which denounces language varieties other than ‘our own.’ As a group discussion activity, decide what varieties of language that you speak are languages, dialects, vernacular, patois, or koine, and on the other hand what are your particular styles/registers and accent, and how do these interact? Do you use one language for certain registers and a different one for others?