Marine Protected Areas and black guillemot (Cepphus grylle)

advertisement

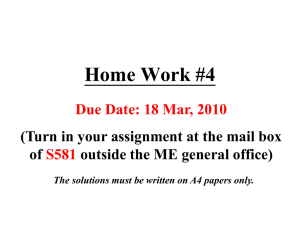

Black Guillemot and Marine Protected Areas Marine Protected Areas and black guillemot (Cepphus grylle) Position paper for 4th MPA Workshop, Heriot Watt 14-15 March 2012 Purpose of document 1. Black guillemot is the only bird species included on the MPA search feature list for Scottish territorial waters. Currently the only protected area measure for black guillemot is the existence of a small number of Sites of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI). 2. The purpose of this document is to summarise the approach being used to select MPA search locations for black guillemot, and to establish the degree to which existing protected areas such as Special Protection Areas (SPAs) and Sites of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) can provide the coverage necessary to address the site protection requirements for this species. The paper also considers the overlap with MPA search locations identified for other features. 3. MPA search locations for black guillemot are assessed against the OSPAR principles, and where appropriate gaps identified. In addition, the degree to which protection is provided by the existing protected area network is assessed, and the nature and extent of additional measures that may be needed to address such gaps are identified. 4. A summary of MPA search locations is provided in the report. Summary 5. Black guillemot is considered here as a MPA search feature. The rationale for selecting sites is developed, and the focus is directed towards selecting sites based on the existing protected area network, especially SPAs with marine extensions, but also where appropriate, SPAs without marine extensions and SSSIs. 6. MPAs will contribute to black guillemot conservation through identification of sites with large aggregations (at a GB scale), given that such sites are likely to be used all-year round by some or all individuals, for breeding feeding and maintenance behaviours. 7. Data used is based on the Seabird 2000 dataset, with reference made to figures within the earlier Seabird Colony Register. 8. A minimum of four search locations are suggested, with a maximum of six, involving duplication of search locations in the North and West MPA regions given the importance of these regions and to maximise connectivity. In the North MPA region Fetlar SPA in Shetland and a possible site in Orkney (Papa Westray, or Rousay SPA or Hoy SPA). In the West MPA region, Monach Isles SPA and Rum/Canna SPAs. In the East MPA region, East Caithness Cliffs SPA and in South-west MPA region, Sanda SSSI. 9. In OSPAR Regions, there are three search locations in OSPAR Region III, The Celtic Sea (Monach Isles, Rum & Canna and Sanda & Sheep Islands). OSPAR Region II, the Greater North Sea Region, there are also three search locations: Fetlar, Papa Westray & East Caithness Cliffs. 10. Three of these locations overlap with MPA search locations for other MPA search features (Fetlar, Rum/Canna and Sanda). 1 Black Guillemot and Marine Protected Areas 11. The seaward boundary will lie at most 2km from shore as this distance would appear to contain the majority of foraging activity based on limited survey and research findings. The 2km distance coincides with most but not all SPA marine extensions. 12. Management should maintain populations and where necessary, enhance resilience to change. Map showing MPA search locations identified for black guillemot 2 Black Guillemot and Marine Protected Areas Background 13. Black guillemot is a member of the auk family, in the genus Cepphus and is closely related to pigeon guillemots and spectacled guillemots. It is widespread globally with an estimated population of 400-800,000 mature individuals1. Image downloaded from http://www.planetofbirds.com/charadriiformes-alcidae-black-guillemot-cepphusgrylle 14. In the UK and Ireland it is largely restricted to Scotland with smaller numbers elsewhere, especially including the island of Ireland. The latest population estimate and breeding range is considered to be about 43,000 mature individuals with over 37,000 in Scotland1. 15. It is almost entirely confined to inshore waters and unlike other members of the auk family, is largely sedentary, although juvenile black guillemot are known to disperse after fledging with median distance moved being about 10km in Britain and Ireland (reference needed). Birds may aggregate into larger flocks after the breeding season (during which birds are flightless), and may then disperse to sheltered coastal locations, not necessarily close to their breeding location. There is some evidence that birds from islands and locations lacking shelter from winter storms move further into areas where such shelter can be found (BirdLife International (2012)). 16. Feeding is undertaken in sheltered waters, generally less than 50m deep and birds will take a wide variety of prey (mostly from the benthos), including small fish such as sandeels (Ammodytes spp.) and butterfish (Pholis spp.) and invertebrates. Some birds may travel long distances along the coast (in excess of 13km) but rarely venture far from shore with maximum distance from the shore being about 5km (BirdLife International (2012)). 17. There is some information which suggests close association with sub-littoral kelp beds, which may highlight the importance of this habitat for this species (BirdLife International (2012)) 18. Nesting takes place in rock cavities and crevices along cliffed coastlines. Birds attend colonies in early spring and may spend some time on the water, close to breeding sites as well as on land, near prospective nest sites. Unusually (for 1 Seabird 2000 (Mitchell et al. 2004 Seabird populations of Britain & Ireland). 3 Black Guillemot and Marine Protected Areas auks), black guillemots lay two eggs. This ability does allow fairly rapid response to population change (such as oil spills from the Esso Bernicia and Braer). 19. There is some evidence of population declines in parts of Scotland (especially the west and south west) with increases elsewhere (especially in Shetland). However, issues such as census methods and timing can have a considerable influence on pre-breeding counts (the standard census method), and some of the apparent trends may be survey artefacts. However, issues such as predation by introduced mammals (mink and brown rats), are real concerns and such causes of change probably highlight very real threats to the black guillemot population (Mitchell, 2004) Distribution in Scottish, GB and Irish waters 20. The distribution of black guillemot in Britain and Ireland is given below2. The distribution in Scotland is largely northern and western with the majority of breeding individuals in the Northern isles 21. The most recent data source giving contemporaneous data is that from the Seabird 2000 dataset. The great majority of the British & Irish coastline was surveyed and results published (Mitchell et al. 2004)2. 22. The GB, Irish and Isle of Man population is given as 42,683 individuals. Of this total 37,505 (~88%) individuals were recorded in Scotland; 7 in England; 602 in the Isle of Man and 4,541(~11%) in AllIreland (Northern Ireland held 1,174 individuals). 23. The GB population of 37,540 individuals is about 5%-15% of the estimated world population. 24. In Scotland, the break down by OSPAR3 & MPA region is given in the table below: 2 Map taken from Seabird 2000 (Mitchell et al. 2004 Seabird Populations of Britain & Ireland). 3 For black guillemot, the relevant OSPAR Regions are Greater North Sea (comprises East and North MPA Regions) and Celtic Seas (comprises West and South-West MPA Regions). 4 Black Guillemot and Marine Protected Areas OSPAR Region Population Count Percentage in MPA Region Celtic Sea 1,145 individuals 3.1% Celtic Sea 13,165 individuals 35.1% 22,068 individuals 58.8% 1,127 individuals 3.0% MPA Region South-west Region West Region North Region East Region Percentage in OSPAR Region 38.2% Greater North Sea Greater North Sea 61.8% 25. No black guillemots were recorded in the Far-west MPA region (which includes Rockall). 26. The majority of birds are found in the north (~60%) and west (~35%). The population in the East MPA region is dominated by the population along the Caithness coastline. 27. There has been very little change overall in GB since the Seabird Colony Register (published in 1985), as numbers in Scotland have increased by 1%. However, this masks apparent declines in the south and west set against substantial increases in Shetland. Issues surrounding counts are discussed later, so considerable caution has to be exercised with the data. However it is possible that there are real, underlying drivers of change (such as non-native species) in different parts of Scotland and this is also considered further, later in this document. Role of Marine Protected Areas for black guillemot 28. Marine Scotland’s Marine Nature Conservation Strategy adopts a three-pillar approach to conservation in the marine environment. These are: species protection; site protection and wider seas measures. 29. Black guillemots are protected under the Wildlife & Countryside Act (1981) against taking, injuring or killing, though as they are not species listed on Schedule 1 they are not protected from disturbance during the breeding season. Black guillemot is not deliberately persecuted in Scottish waters, though there may be an incidental take through entanglement in nets and some individuals have been found in creels (Ewins 1988, Okill 2002). 30. Within territorial waters, the role of MPAs will be to give protection to significant aggregations of black guillemot, which cannot be achieved through existing protected area mechanisms. While SSSIs can (and have been) identified for black guillemot (see later), the geographical limits to SSSI selection stop at mean low water spring tides, and essential areas for foraging cannot be protected through the existing SSSI mechanism. 31. Most seabirds breeding in Scotland are given protection under the EU Birds Directive as they are either Annex 1 species or they are considered to be migratory. Black guillemots in the UK and Ireland are not considered to be migratory and have therefore not been including as a species for which Special Protection Areas (SPAs) have been identified and classified. 32. It is for this reason that it is considered appropriate to identify Marine Protected Areas for black guillemot. 5 Black Guillemot and Marine Protected Areas Areas appropriate to safeguard mobile species in the MPA process. 33. In relation to mobile species, the MPA Selection Guidelines consider that Nature Conservation MPAs are appropriate for contributing to the protection of the following: a. significant aggregations of communities of important marine species in Scottish waters; b. essential areas for key life cycle stages of important mobile species that persist in time, including habitats known to be important for reproduction and nursery stages; and, c. areas contributing to the maintenance of ecosystem functioning in Scottish waters. 34. This approach is intrinsically linked to the concept of ‘critical habitats’, areas upon which species are strongly dependent, or areas where species show high fidelity (essential for day-to-day well-being and survival and to maintain healthy populations). 35. For black guillemot these three broader categories can be more clearly articulated according to a number of different types of areas as follows (reflecting our understanding of the ecology of the species): Significant aggregations of communities of important marine species in Scottish waters a. Places used regularly for feeding, breeding and socialising. b. Locations where associated and supporting activities (e.g. courtship, resting, playing, communication) take place. c. Locations with regular seasonal concentrations. 36. Within territorial waters, the perceived MPA role in relation to black guillemot is to provide protection to significant aggregations and to essential areas for key life cycle stages. The MPA designation will ensure specific conservation objectives are met and that an assessment is carried out for activities likely to impact upon black guillemots. This will offer heightened and appropriate protection in those areas where black guillemots are potentially most sensitive. Network considerations for black guillemots 37. MPA search locations should cover the range of geographical variation in Great Britain’s sea areas (in practice this means that sites will lie within Scotland given the very small English & Welsh black guillemot population). Black guillemot are largely sedentary and although juvenile dispersal is probably responsible for most emigration, which can be over very long distances (Ewins 1988), most black guillemot (as with many other seabirds) exhibit a degree of natal fidelity when selecting breeding locations. Frederiksen & Petersen (2000) showed that most breeding black guillemot in Iceland did not disperse and settle to breed more than about 10km from their natal colony. Selection of search locations across the range will ensure good representation across the geographical extent of this species’ range in Scotland. This will require replication of sites across the breeding range, including possibly multiple sites within each of the MPA (and OSPAR) regions (apart from the far west, where black guillemot do not occur in any significant numbers as JNCC data suggests that black guillemot is virtually absent from the Far West area). 38. MPA search locations should be distributed so as to maximise connectivity in a species that is relatively sedentary. This may mean that when considering 6 Black Guillemot and Marine Protected Areas replication of sites, selecting sites that enhance connectivity should be preferred. Given that relatively few black guillemot juveniles move further than about 50km from their natal colony (Okill 2002), having a spread of protected areas managed appropriately across the geographical range of the species is likely to be essential. This does not imply that sites need to be spaced very 50km or so, but where there may be several possible locations within an OSPAR Region, replication and representation of sites that are spread across the latitudinal gradient should be preferred as opposed to any clustering that might arise from other consideration (such as size and/or viability). Connectivity may be especially important in the south west where Scottish populations will link with the Irish population. 39. Search locations should be as large (with respect to numbers not area covered) as possible because large sites with high numbers are likely to show less inter-count and inter-annual variability arising from statistical count error; and because larger areas will engender greater resilience as well as encompassing the full range of habitat selection. 40. To ensure viability, search locations should contain more than 1% of the GB population (see discussion in following section for more detail). Process for identifying MPA search locations for black guillemot 41. The development of the network for black guillemot has focussed on the contribution of existing protected areas as initial assessment work indicated this would give sufficient representation and replication of sites. 42. The order in which existing protected areas were considered includes: The contribution of existing Sites of Special Scientific Interest notified for black guillemot. Identification of MPA search locations that may coincide with SPAs with marine extensions and the contribution these could make. SPAs with terns are also included as these may also require marine additions to existing SPAs Identification of MPA search locations that coincide with MPA search locations identified for other MPA search features and the contribution these could make. 43. It should be noted that existing protected areas will lack elements vital to overall protection of black guillemot. For SPAs with marine extensions, black guillemot cannot be a qualifying species. There are differences in habitat use and behaviour that mean that for black guillemot to be protected within an SPA classified for other seabirds, the SPA would have to be overlain with a new MPA. For SSSI and SPAs without marine extension there may be no marine element and this will require definition if adequate protection is to be given to foraging areas (see later). This would also require the designation of a new MPA. 44. In general search locations should hold in excess of 1% of the GB population (rounded to 376 individuals)4. Selection of search locations in excess of 1% of the GB population will ensure such sites are much more likely to be viable though viability depends on a number of factors, which can be considered after the threshold of 1%. These include: a. Known trends: in most cases there will only be two data points - Seabird Colony Register, (counts undertaken 1985) and Seabird 2000, (counts undertaken ~2000) so trends will be hard to identify; 4 Variability in the data (due to count conditions and the number of non-breeding birds present also needs to be addressed). 7 Black Guillemot and Marine Protected Areas b. Favourable management: NNRs are other sites under management might be preferred; c. Absence of known predatory non-native species, such as cats and brown rats; d. Harmful activities in the marine environment; and e. Productivity (there is no known data, so it will not be possible to use this factor in practice). 45. Search locations, should, where possible provide linkage to the remaining GB and All-Ireland distribution of black guillemot. Hence this may require site(s) at the edge of Scottish range, e.g. within the SW MPA region, though these may occur in areas where numbers are lower than the stronghold North and West MPA regions. Assessment and marine regions 46. The analysis described below has been undertaken on the basis of MPA Regions. There are four MPA regions that contain black guillemot as already highlighted. These four regions are contained within the larger OSPAR regions. OSPAR Region II (The Greater North Sea) is equivalent (for black guillemot) to North MPA region and East MPA region. OSPAR Region III Celtic Seas is equivalent (for black guillemot) to West MPA Region and South-west MPA region. 47. The analyses and conclusions vis a vis MPA search locations is not affected by using the two regional basis for assessments, as the arguments for replication, representation and connectivity are applied at the scale of the species’ distribution in Scotland. Evidence base s2k 48. Data. Data for analyses Black Guillemot Count Data - SCR vs S2000 is the Seabird 2000 dataset for black 2500 guillemot. There is no contemporaneous, comparable data. It is 2000 assumed that the data for individual sites is representative (see 1500 Annex 2) even though it is based in almost all 1000 cases on a single count. Consistency over time was 500 investigated using comparable Seabird Colony Register data 0 for a sample of 50 sites 0 500 1000 1500 2000 that range in size from 1 individual to over scr85 2,000 individuals. The s2kSeabird 2000 data (Celtic) results of the analysis s2kSeabird 2000 data (Greater_North_Sea) (see figure, right) shows that site numbers are remarkably consistent between the two surveys, though unsurprisingly, count variance appears to increase with count size. 49. The SSSI network. There are four SSSIs designated for black guillemot in Scotland. These are shown in the table below. This does not include any SSSI underpinning 8 Black Guillemot and Marine Protected Areas any SPA as the relevant SSSI do not include black guillemot as a species for which the site is designated. 50. The SSSI network contains 4.3% of the GB population of black guillemot. Two sites fall below nominal 1% thresholds for SSSI designation. 51. The group of SSSI for black guillemot cannot be construed as a coherent network of sites, both in terms of the proportion within a ‘network’ nor in terms of the geographical distribution. Furthermore there are no marine extensions (as there are for some seabird SPAs) and some form of marine boundary would be needed to ensure adequate protection for this species. 52. Number (max) Number (min) Importance Notes North MPA Region Mousa Holm of Papa Westray 166 211 166 211 0.44% 0.56% SPA (no extension) SPA (no extension) West MPA Region Monach Isles 819 819 2.2% SPA (no extension) South West MPA Region Sanda Island 406 406 1.1% Site name 53. The SPA Network An analysis of the Seabird 2000 data for presence of black guillemot within the boundaries of SPAs was undertaken. The detail of this is given in Annex 1 but it should be borne in mind that the numbers counted are at best an approximation of numbers present as breeding birds with the SPA boundary. Reasons for this are given in Annex 2. 54. A total of 34 SPAs were identified that host black guillemot. Not all of these are seabird SPAs but include sites with other classified features but which extend to the coastline (usually to HWMS). The table below, indicates for each SPA, the approximate size of the population (based on Seabird 2000 counts); the existence or otherwise of a seaward extension; and any associated notes. The table is broken down into separate MPA regions (though two SPAs are bisected by an MPA region – Cape Wrath and North Caithness Cliffs). 55. About 6,997-7,218 individuals are hosted by these 34 SPAs which represents ~1719% of the GB population, though this includes a few sites where numbers are so small (<50 individuals) that they might not be considered to be ‘viable’ in terms of population persistence in the long term. 56. There are no SPAs in SW region which host black guillemot, though. The great majority are hosted by the North MPA region & West MPA region. 57. SPAs hosting notable concentrations of black guillemot are: East Caithness Cliffs (Caithness); Fetlar (Shetland); Otterswick & Graveland (Shetland); Papa Westray (Orkney); Monach Isles (Western Isles); and Rum, Canna & Sanday combined (Inner Hebrides). 9 Black Guillemot and Marine Protected Areas This Table lists all SPAs for seabirds within the overall range of breeding black guillemot in Scotland and assesses numbers of breeding individuals as per Seabird 2000 data. Site name Ailsa Craig Oronsay & South Colonsay North Colonsay & Western Cliffs Coll Treshnish Isles Rum Canna & Sanday Mingulay & Bernaray Monach Isles Shiants North Rona & Sula Sgeir Priest Island Handa Cape Wrath North Caithness Cliffs Hoy Copinsay Marwick Head Rousay West Westray Papa Westray Calf of Eday Pentland Firth Islands Fair Isle Sumburgh Head Mousa Noss Papa Stour Foula North Roe & Tingon Otterswick & Graveland Fetlar Hermaness & Saxavord East Caithness Cliffs Number (max) Number (min) Percentage GB Seabird extension Seaward boundary 24 55 24 55 0.06% 0.15% Yes No 2km - 74 17 14 645 204 43 819 19 7 131 1 91 200 302 91 15 232 108 408 109 158 191 40 166 112 234 79 300 526 950 186 446 74 17 14 645 204 43 819 19 7 131 1 91 200 302 91 17 305 143 408 109 158 191 46 166 112 246 92 320 536 1000 186 446 0.20% 0.05% 0.04% 1.72% 0.54% 0.11% 2.18% 0.05% 0.02% 0.35% 0.00% 0.24% 0.53% 0.80% 0.24% 0.04% 0.72% 0.33% 1.09% 0.29% 0.42% 0.51% 0.11% 0.44% 0.30% 0.64% 0.23% 0.83% 1.41% 2.60% 0.50% 1.19% Yes No No Yes Yes Yes No Yes Yes No Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes No Yes No Yes Yes No Yes No Yes No No Yes Yes Yes 1km 4km 1km 2km 2Km 2Km 2km 2km 2km 2km 2km 1km 2km 2km 2km 2km 2km 2km 2km 2km 2km 2km MPA search location proposals 58. MPA East Region & OSPAR Region II The distribution of black guillemot in this area is almost wholly confined to the north (eastern) corner of Caithness & Sutherland. While there are a few individuals further south (along the coast of Moray and Aberdeenshire, the most abundant population is along the Caithness Cliffs (particularly within the East Caithness Cliffs SPA). The East Caithness Cliffs SPA is underpinned by three SSSI, with ~100% overlap over the terrestrial component of 10 Black Guillemot and Marine Protected Areas the SPA. The SPA has a 2km marine extension. The approximate number of birds within the SPA/SSSIs is 446 (Seabird 2000), which is ~1.2% of the GB breeding population. 59. The only area of overlap with an MPA search location identified for other features is with Sinclair Bay, and even here the overlap is minimal (though the area may be used by foraging black guillemot). 60. Recommendation It is recommended that an MPA search location is considered in this area, which will coincide with the SPA/SSSI boundaries of the East Caithness Cliffs SPA (with its marine extension). Inset shows general location of East Caithness Cliffs SPA East Caithness Cliffs SPA with marine extension 61. MPA North Region & OSPAR Region II The North MPA region holds the biggest proportion of the population (nearly 60%). The bulk of the population is found around the coastlines of Orkney and Shetland, though there are significant numbers along the North Caithness coastline (along the coast to Cape Wrath from Duncansby Head). Replication of search locations within North MPA Region is proposed here, to reflect the geographical range and importance of North MPA Region for black guillemot 62. There are a number of SPAs that hold significant numbers of black guillemot in North MPA Region. 63. Fetlar SPA and marine extension holds about 950-1,000 black guillemot. It is worth noting that this SPA overlaps with the Fetlar to Haroldswick search location. This (larger) area will in all likelihood, contain a large black guillemot breeding population as the site includes marine habitat that is not included in the Fetlar SPA & marine extension. Fetlar as a whole showed an increase of 15% in black guillemot numbers since Seabird Colony Register though this is probably within expected count variability. 64. In addition, there are a number of SPAs within Orkney that contain significant numbers of back guillemot. The largest site is Papa Westray SPA (holding just over 1.1% of GB population counted during Seabird 2000). Papa Westray is composed of two separate SPAs, both for breeding terns, though any additional marine area to these SPAs has not yet been identified. Rousay SPA and Hoy SPA also contain ‘nationally significant’ numbers (0.7% and 0.8% respectively) and both have marine extensions. None of these Orkney sites overlaps with an MPA search location identified for other features. North Hill, Papa Westray and part of Hoy are nature reserves managed by the RSPB. 11 Black Guillemot and Marine Protected Areas 65. Recommendation. It is recommended that Fetlar SPA is selected as a search location along with a site in Orkney, with marginal preference for Papa Westray SPA or either Rousay SPA or Hoy SPA. Counts in all three locations showed a decline since Seabird Colony Register [-27%, -17% and -7% respectively] though given variability in counts (see Annex 2) this is probably within expected count variability. Fetlar SPA and marine extension Rousay and marine extension Papa Westray (North Hill & Holm) Hoy and marine extension 66. MPA West Region & OSPAR Region III. The West MPA region holds a large number of black guillemot though numbers are more scattered and generally at lower densities than in North MPA region. Although the region holds fewer black guillemots than the North MPA region, they occupy a wide geographical range, and it is proposed that additional/alternative search locations are identified. 67. In the Western Isles, there are significant numbers of black guillemot on the Monach Isles SPA (about 820, about 2.2%) which is also a SSSI and (currently) a NNR. There are no other significant concentrations of black guillemot on the Western Isles that overlap with protected areas apart from Mingulay & Berneray (SPAs) that hold about 40-50 black guillemot. The Monach Isles SPA currently has no marine extension as the SPA is classified for breeding terns, among other breeding species. 68. In the inner Hebrides the island SPAs of Rum and Canna & Sanday host a large population of black guillemot (approximately 850, or about 2.25% of the GB population). Rum has a 4km extension and Canna and Sanday have a 1km marine extensions (see later). Perhaps importantly, these SPAs overlap with the Small Isles search location identified for other features and Rum is managed as a NNR. Within the MPA search location, there are a further 433 in the other small isles (Eigg & 12 Black Guillemot and Marine Protected Areas Muck), though neither has an appropriate SSSI and/or SPA classification (however, the MPA search area includes waters off the west coast of Eigg and ends just to the north of Muck). 69. Further south the Tiree & Coll SPAs includes a small population of black guillemot (about 90 individuals, well below 1%). The west coast sealochs may hold very small numbers but these will generally be in single figures and are unlikely to contribute to the MPA network significantly. The Treshnish Isles has been put forward as a third-party proposal for seabirds but hold very small numbers and cannot be regarded as offering significant site protection to black guillemot. 70. Recommendation The principal sites for black guillemot in the West MPA region are likely the Monach Isles SPA (also SSSI for black guillemot and NNR) though not a search location for any other MPA search feature, and the Small Isles of Rum and Canna & Sanday SPAs (part of the Small Isles search location). It is proposed that selection of both sites will provide sufficient representation in the West MPA region, reflecting the geographical variation from an exposed Atlantic locale, to more sheltered inshore areas with contrasting oceanographical conditions and management activities. Trend data for these locations show that numbers have been more or less stable between Seabird Colony Register and Seabird 2000. Monach isles SPA Rum, Canna & Sanday SPA 71. South West MPA Region and OSPAR Region III Numbers of black guillemot in the South West MPA area are lower than elsewhere (apart from Far West Area), though populations form an important ‘link’ with the Northern Irish/Eire population. The only area that has significant numbers of black guillemot are the two small islands to the south of the Mull of Kintyre (Sanda & Sheep Islands). Both are designated as SSSI (Sanda Islands SSSI) for black guillemot. These islands host about 400 black guillemot which is just in excess of 1%. These islands are enclosed within the MPA search location known as the Clyde Sill. There are small numbers of black guillemot on Arran and in some of the Clyde sea lochs though the overlap with the MPA search location in this area is not good. There are no other areas that hold significant numbers of black guillemot in this region. 72. Recommendation It is recommended that Sanda Islands SSSI is selected as a MPA search location for black guillemot for the significant numbers that occur here and the connectivity that it provides with the Irish population. However, further discussion with Northern Ireland concerning their Marine Protected Area programme, may affect the need (and therefore likelihood) of proceeding with this search location. There is no marine extension, as this is the only site that is only SSSI . Sanda/Sheep Islands saw an increase in numbers counted .between Seabird Colony Register and Seabird 2000. 13 Black Guillemot and Marine Protected Areas Inset shows location of Sanda Islands with Ailsa Craig to east Issues and opportunities 73. SPA Boundaries. Most SPA landward boundaries will encompass the area within which black guillemot occupy nest locations. Black guillemot are almost exclusively cliff nesters utilising crevices, holes under rocks and other concealed locations. In some areas such locations may limit the size of the local population. 74. SPA Protection. While SPAs may host black guillemot, the conservation objectives do not provide any protection for the species, except incidentally where a plan or project that affects, a species for which the site is classified (e.g. some other coastal seabird)also affects black guillemot This begs the question as to what mechanism can be used to provide adequate protection and this question is left open to further discussion. The conservation objectives may not provide little protection for the inshore foraging habitat used by black guillemot (which is mainly over the benthos). Defining seaward boundaries for black guillemot 75. There is limited evidence from the literature on how far black guillemot travel out to sea, and therefore at what distance any seaward boundary should be set. Ideally, a research programme, across the range should be undertaken, probably using tracking technology to see how birds use the inshore environment. This can be enhanced by developing appropriate parametric or non-parametric models based on significant habitat and environmental associations (as has been undertaken for a number of species, such as red-throated divers – Dean et al. unpublished JNCC report,). However, the timescales that are required for the MPA selection process do not permit the ‘luxury’ of a prolonged research programme (though some work under FAME5 may take place in summer of 2012). 76. Bearing this in mind, the only viable option is to use what information exists in the literature to develop an approach to boundary setting that has some empirical basis. The principal source of data on black guillemot foraging ranges has been taken from the Bird life International database on seabird foraging ranges ((see http://seabird.wikispaces.com/Black+Guillemot). There are a number of key conclusions from this analysis. 77. In the Bay of Fundy birds generally foraged within about 1km of the shore. 78. Black guillemot forage close inshore, generally in waters less than 30m but up to 50m in some places. The mean of all studies on distance flown is 4.96km, though this encompasses a widely varying range of mean (and median) values. 5 Future of the Atlantic Marine Environment 14 Black Guillemot and Marine Protected Areas 79. Black guillemot may, under some situations, fly long distances to feed in waters adjacent to a coastline some distance from the nest site e.g. birds on islands may fly to the nearby mainland. In some studies this leads to a bimodal distribution in foraging distances. 80. In the GB and Ireland the few studies undertaken suggest that most birds forage close to breeding sites but that longer distances are flown (as above). There are two Scottish (BirdLife International wiki) studies cited: an at sea survey data along the coast on Caithness, during which black guillemot were always found within 5km of the coast, and radio tracking study from Orkney. In contrast, to the Caithness data, the radio tracking data from Orkney gave a bimodal median distribution of travel of 1km and 6.5km, though the median distance offshore was only 300m. Finally work at an Irish colony showed that birds generally foraged within 1km of the colony, though they did fly to the mainland coast occasionally, a distance of about 7km. 81. Elsewhere a set of studies from Canada, Finland, Denmark and Iceland found that black guillemot foraged at ~1.5km, 1.5-4km 0.5-4km and 2-4km from nest sites (Bird Life International wiki). 82. We can use simple parametric models to approximate the way birds distribute themselves in the inshore region. Assuming that the distance birds fly can be approximated by an exponential distribution (most birds will fly short distances), then we can use the summary statistics for the data that is available (referred to above) to indicate the distance offshore that most feeding birds are likely to occur within. 83. It is also inevitable that boundary setting will need to ignore birds that fly over long distances, because such movements are likely to be dependent on local circumstances and any generalization will be impossible. 84. On the basis of the Papa Westray data, the median distance birds occur offshore is 300m (0.3km), virtually all birds (>99%) using the inshore area adjacent to the breeding coastline might be expected to occur within a maximum of 2km offshore. The Caithness data suggests that all birds are likely to be found within 5km of the coast: using an exponential model, this would suggest that ~95% of birds will be found within 2km of the coastline Black guillemot - cumulative distance from coast Caithness coast 1.200 1.200 1.000 1.000 0.800 0.800 distance distance Black guillemot - cumulative distance from coast Papa Westray 0.600 0.600 0.400 0.400 0.200 0.200 0.000 0.000 0 1 2 3 4 CDF . 5 6 7 8 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 CDF 85. Analysis of black guillemot within SPAs highlighted the fact that for most SPAs, the existing seaward extensions coincide with the distance from the coast that black guillemot forage out to. The figures above illustrate the cumulative distribution function for distance offshore based on the exponential model for Papa Westray (left) and Caithness (right) data. 15 Black Guillemot and Marine Protected Areas 86. It is not possible to model the Rockabill data as ‘most’ is not defined in any meaningful way, but it’s worth noting that even under a model that uses the Caithness data, over 78% of birds will be found within 1km of the coast. 87. Conclusions and recommendation: It is suggested that a seaward boundary of at least 1km will encompass the majority of feeding birds that forage along coastline adjacent to the breeding coast. A boundary out to 2km will encompass >95% of birds. There is an important caveat here in that the sample size is small, and it does not address birds that fly much longer distances to nearby coastlines (e.g. for birds nesting on islands). Given this a potential site boundary of at least 1km offshore and possibly 2km offshore will be adequate to protect black guillemot. For some of the SPAs identified that coincide with possible search locations for black guillemot, a marine extension already exists, which (in most cases) is 2km. This suggests that existing marine extensions for seabird SPAs will be sufficient to encompass black guillemots foraging in the breeding season. The data from other breeding locations is generally consistent with such a distance. 88. “Winter foraging”: The previous analysis deals largely with breeding birds and all the data applies to birds during the period May to June. However, the Caithness survey data was all-year round so the conclusions are likely to hold true for wintering birds. While it is known that black guillemot do (probably) forage further in winter as they are less tied to their central place (the nest site), the use of a 1-2km offshore boundary is still likely to give protection to a significant proportion of the resident population. It is known that some birds undergo localised dispersal for moult purposes, but these are short-term movements. 89. Depth considerations: Since black guillemot do not forage in waters greater than 50m and most birds forage within a depth range up to 30m boundary setting could be constrained locally to depths <50m and/or coincident with offshore kelp forests, a preferred foraging habitat. In this case boundaries might be set closer to shore than 2km. Development and approach to management 90. Key pressures that are adversely affecting black guillemot include: a. Marine environment: Loss or damage of foraging habitat, e.g. sub-tidal kelp forests; entanglement in fishing nets; oil pollution; and potentially inshore marine renewables (such as tidal turbines – Furness & Wade 2012) b. Breeding habitat. The most significant threat is likely to originate from invasive non-native species (INNS), especially mink and other mustelids. While otter predation is common throughout the range, it does not appear to drive declines, whereas predation by American mink, which are smaller and therefore able to access a wider range of nest sites may be limiting black guillemot populations, where they occur. Disturbance and onshore development may be local problems, but not on the scale of INNS. 91. Management should aim to maintain and to improve resilience (e.g. through appropriate biosecurity measures, habitat management and preparatory work such as oil spill contingency plans). 16 Black Guillemot and Marine Protected Areas Next steps 92. Further data validation may be helpful. Given that data on which proposed MPA search locations are being selected are now over 10 years old, further survey work would help to underpin the case for particular sites. 93. Further work on how black guillemots use inshore marine areas would also be helpful, e.g. through a dedicated radio telemetry project. Indeed work is planned for 2012, and SNH funding is being sought for this. References BirdLife International (2012) Species fact sheet: Cepphus grylle. Downloaded from http://www.birdlife.org on 04/03/2012. Recommended citation for fact sheets for more than one species: BirdLife International (2012) IUCN Red List for birds. Downloaded from http://www.birdlife.org on 04/03/2012. BirdLife International http://seabird.wikispaces.com/Black+Guillemot Dean, B.J., Webb, A., Lewis M., Okill, D. and Reid, J.B. Identification of important marine areas in the UK for red-throated divers (Gavia stellata) during the breeding season. Unpublished JNCC report. Ewins, P. J. (1985) Colony attendance and censusing of Black Guillemots Cepphus grylle in Shetland. Bird Study 32: 176-185 Ewins P. (1988) An analysis of ringing recoveries of Black Guillemot Cepphus grylle in Britain and Ireland. Ringing & Migration 9: 95-102 Frederiksen M., & Petersen, A. (2000) The importance of natal dispersal in a colonial seabird, the Black Guillemot Cepphus grylle Ibis pages 48–57, January 2000 Furness & Wade (2012) Vulnerability of Scottish Seabirds to Tidal Turbines and Wave Energy Devices. Unpublished report to Scottish Natural heritage. Mitchell, P. I., Newton, S. F., Ratcliffe, N. and Dunn, T. E. 2004. Seabird Populations of Britain and Ireland. T and A D Poyser; London. Okill, D. (2002). Black Guillemot. In Wernham, C.V., Toms, M.P., Marchant, J.H., Clark, J.A. Siriwardena, G.M. & Baillie, S.R. (eds) The Migration Atlas: Movements of the Birds of Britain and Ireland: 405–406. T. & A.D. Poyser, London. 17 Black Guillemot and Marine Protected Areas Annex 1 Approach taken and data sources The principal data source is the Seabird 2000 dataset. Black guillemot are rarely counted in UK except during periodic seabird census events. The next is not due for another few years and the previous survey would have been under seabird Colony Register (published in the late 1980s) so much of that information will be very dated. There are some periodic counts undertaken by Martin Heubeck in Shetland and I suspect a few other counts as well, but we are faced with a paucity of data, much of it based on single counts. Mindful of this the approach taken was as follows. Data from Seabird 2000 gives numbers (usually individuals at sea or on land) for a defined section of coast. In some cases a single co-ordinate is given for a small island, but in most cases a start and end point is noted along with a unique section identifier. The start and ends points were mapped in GeoView and SPA boundaries overlaid for each of the 50 or so SPAs that have at least some section of coast associated with the site (an association is simply defined as the boundary extending to the coast, usually HWMS or LWMS). A series of maps were produced for each SPA. This was necessary because start and end points do not coincide with start and end points of protected areas [This is some thing that needs to be addressed in any future national seabird survey]. The number of black guillemot in each section included within the SPA boundary (with or without a marine extension) was totalled. Where sections crossed SPA boundaries and assessment was made of the likely number in the SPA and outside the SPA. Where there was uncertainty a maximum and minimum total was calculated. This is why the tables contain maximum and minimum figures. An example map for West Westray is shown here. Note that sections 617 and 626 both cross the SPA boundary. 18 Black Guillemot and Marine Protected Areas Annex 2 Data Uncertainties and Variability We need to be aware of this and not treat the information as absolute but indicative of general locations where black guillemot are likely to occur in significant numbers. This has a number of consequences: We should be careful about using numerical thresholds to define sites. As you know the 1% criterion is commonly used to define protected areas for birds and for many species this works well, but only where we have reliable data over a number of years. Neither of these conditions applies to black guillemot. This is not to say we cannot use the 1% threshold, but it would be disingenuous to state the site x holds (say) 1% of the UK population when in reality this may range from 0.8% - 1.2% based on inter-count variability for large ‘sites’6 when only one count is made (as assessed by Pete Ewins on Mousa (Ewins, 1985). This suggests that we should favour ‘sites’ that hold large numbers (generally >> 1%) over smaller sites, and that an aggregation of contiguous count sections/sites will provide a more robust indication of overall site importance (because large sites have lower count variability). Variability between years is similarly likely to complicate the picture, though as a long lived species with a sedentary distribution, such variability should be limited. However, as Ewins (1985) has highlighted, the proportion of nonbreeders at any site varies considerably (57% for one island compared to less than 11% at another) which means that intercount variability can be very high. 90 80 70 60 50 Low count During Seabird 2000 a small number of paired counts were made. A simple plot of these counts shows that there is a reasonably good correlation between the highest and lowest count in each pair (see right), but that a second count could vary by as much as 50%-100%. For example a count of 50 birds on one occasion may mean a count of 25 birds on another occasion or as many as 100 birds on another occasion. Paired counts 40 30 20 10 0 0 20 40 60 80 100 120 -10 High count Another problem is that many counts were undertaken outwith the ideal census time (prebreeding) and at times of day when count variability is likely to be high. Counts were sometimes made of birds on land, though more generally they were of birds on water. Despite the above, we can use the Seabird 2000 dataset to identify locations where there are high concentrations of black guillemots, and specifically to identify locations where such concentrations overlap with existing protected areas and/or MPA search locations. This is the approach that has been taken so far 6 In this context a site is usually a discrete entity such as an island or a defined protected area (SSI or SPA). In Seabird 2000 such sites are often made up from a number of count sections, though for island sites this was rarely the case. 19