With Eyes Wide Shut: Japan, Heisei Militarization and the Bush

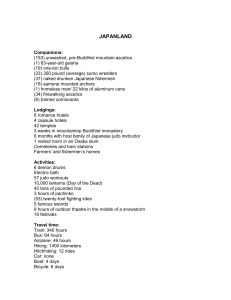

advertisement