general both Jean-Marie and Anne were extremely impressed by

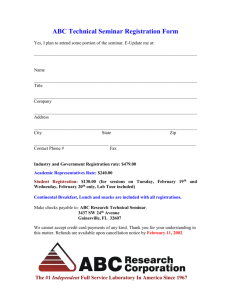

advertisement

New Generations New Connections between Britain and France Report of a seminar 24th November 2004 Introduction Here was a group of “Thirtysomethings” most of whom had never met each other before. They were not quite randomly selected. They were chosen with some regard to gender, experience and institutional background. Coming from business, the arts, academe, politics and government, they represented a reasonable cross section of the educated and successful of their age cohort in both countries. How much should they have had in common? After spending barely seven hours together, they bonded. They were hungry; they wanted more. A “group dynamic” had been created, someone said. Participants in the seminar asked for further contact, another occasion to meet, more exchanges, an ongoing conversation between contemporaries Even allowing for a certain euphoria that builds up at such events – akin, perhaps, to the esprit that makes diplomatic breakthrough possible in tightly-timetabled international conferences – this appetite for extending and deepening links was remarkable. Perhaps it demonstrated that Franco-British dealings in general are in deficit. Over them – the co-chairmen of the Franco British Council, Lord Radice and Jacques Viot nodded in agreement – hung the shadow of (British) euroscepticism. Much depended, they said, on age and the reference points that came from personal experience of politics. Denis MacShane, the British minister, referred to personalities (Harold Macmillan, Edward Heath) who may now have faded from consciousness. Yves Censi, the French parliamentarian, noted a distinct generational sense in France among the sons and daughters of soixante-huitard: was there, he wondered, an analogous British sense of belonging together in time? Perhaps not, but the seminar showed there exists a common, age-specific wish to reach over and make contact – whatever parents and forbears might have done. We travel and visit and deal with one another, but beneath the surface of banal connexions there exists a potential for deeper contact, friendship and exchange; for swapping notes (observed Jonathan Portes) on such common anxieties as pension provision. That word – exchange - came up a lot during the day. It dominated the recommendations for follow-up action 1 participants were asked to make at the end of proceedings. Was it mere curiosity or did this group demonstrate some special talent pour le couplage – that ambiguous phrase leading to badinage (is that any longer a French word?) between the politicians, Yves Censi and Denis MacShane, who joked about its application to the relationship between British prime minister Margaret Thatcher and French President Francois Mitterand. Perhaps our seminar showed only that closer contact sharpens the desire for more intimacy; that, jolted out of everyday and national existences, people (at least these Thirtysomethings) relished the opportunity to learn about each other and compare notes on their experience. Did our day together serve to alter perceptions, to tear veils (those coverings later a subject of some anguished debate on both sides) or to dissolve stereotypes? The culprit, on the British side at least, was easy to identify. It was the media, especially the UK’s national newspaper press. The seminar heard bitter complaint about the treatment of France and of the European Union in British newspapers and in broadcasting, of reporting that had started to merge dishonestly into opinionating, of prejudice and, as bad, great gaps in coverage. Little was heard at the seminar about French media, though some participants worried about a tendency to “blame Brussels”. In the UK the media were judged to have abdicated responsibility for leading the public and articulating a sense of national purpose and future betterment. But Benedicte Paviot said less-thancourageous politicians bore some responsibility, too. At events such as this, said Yves Censi, we should maximise that which unites us and marginalise that which separates us. Age did not seem to belong to the latter category. Yet it was hard to pick up any sense that this age cohort was more or less attuned to events and movements in the respective countries now. Had a group of Thirtysomethings convened two decades ago, would they have produced a radically different agenda of divergences and convergences? Certain issues have risen up the agenda of public attention, notably migration and multiculturalism; our seminar discussed them energetically. But it was hard to see, in France or the UK, an agespecific concern about, for example, social cohesion, fundamentalism and the need to protect core civic values; these themes preoccupy thinking people of all ages. Similarities, Differences and Shared Influences: Perceptions of a New Generation of the Economy The seminar began on a note of difference. In the UK the phrase “Thatcher’s children” has been used of the 2 generation passing into adulthood during the 1980s and early 1990s. Perhaps our seminar did pick up, from the UK side at least, some sense that this generation – now in its thirties – had acquired a fatalistic sense of the state’s incapacity and the futility of attempts to intervene in markets. It’s very much not a sense French men and women of a similar age share. Debate was lively. Liberalism vs etatisme became one of the slogans of the day. Under the Blair government UK policy, said Denis MacShane, rested upon “flexibility”, the expansion of small and medium enterprise and the rest of the Lisbon agenda. We wanted, he said, fewer directions out of Brussels; the view was not unknown in France Yves Censi drily noted. And this was the consensus in the UK, said David Cameron MP. There is more agreement in the UK on the bases of policy than in France or the United States, he argued. Here we concur on the primacy of market economics and the central role of private ownership in economic life. Of course the parties divided over tax, regulation and the extent of the state’s role in national life; but the British, left, right and centre, were wedded to liberalism. William Vereker put the point in stronger terms. Between France and the UK existed “fundamental differences” about the state and political economy. Take corporate ownership. On one side of the Channel large French companies dominated the market while in the UK the economy was open to German, French and American ownership; in London, the lights were kept on courtesy of EdF and no one bothered. In France, however, the recent introduction of private capital had not wrested French energy concerns from their close links with the state or the trade unions. Even an ostensibly right-of-centre politician such as the former finance minister Nicholas Sarkozy believed in market intervention by government and “national champions”. The cost to France was high, Mr Vereker argued. Consumer energy prices were above those in the UK. And tax. Young, energetic French people migrated, not least to London, to avoid punitive taxation. These remarks caused a stir, among participants from both countries. Dogmatic belief in competition had undermined economic confidence in the UK, said Catherine Fieschi, and UK consumers had lost out through the privatisation of the railways; now a damaging, competitive model was being extended to health. UK railways were “a disaster” according to Anwar Akhtar. Private markets could not deliver a safe or cohesive society. He cited the positive role played by a state agency, the Arts Council, in music and culture. Some 3 public sector leaders, however, continued “recklessly to cheerlead the private sector”. Beware generalisations, John Edward chipped in. In Scotland, water had never been privatised. However, James Tugendhat rejected black and white models of public-private sectors for both France and the UK. The idea that French companies were featherbedded was nonsense; on the basis of his own experience some of them were judged “ruthless”. Pierre-Antoine de Selancy took a similar view: strong forces of economic convergence were at work in the world. Both French and British economies faced similar problems of flexibility, employment and growth and companies in both countries realised, or ought to realise, that their staff would only add value if they were committed, and managed accordingly. Pascal Rigaud – noting his personal experience of working in France for a UK-owned company – wanted more exchanges within and between companies on either side of the Channel. Addressing a contemporary problem of French public policy, he wondered about statutory restrictions on weekly hours of work: the 35-hour scheme might inhibit the effort to reclaim a sense of the value of work. Eluned Haf, also reflecting on personal experience of work inside and outside the UK, worried about too rigid divisions between public and private sectors and urged the need for partnership and a better division of labour between business and government. Now the French trained their heavy guns on William Vereker’s contention that the British economy was in a better state than the French, thanks to Thatcherite liberalisation. You are consuming our nuclear energy, Arnaud Leparmentier, noted, referring to the importation of electricity into the UK from France. Liberalisation in energy markets had led to shortages in the UK and the botched privatisation of British Energy had had to be unwound. As for rail, the industry depended on government subsidies. That said, things were changing in France. Perhaps, he mused, the broad-bottomed Gaullist-inspired consensus about energy, especially France’s nuclear programme, would come to an end with the privatisation of EdF. While urging discussants to move beyond a “Manichean vision” of public and private sectors, Jeannette Bougrab explored the role of the French state in building infrastructure and pumping investment into sector, such as rail, where the private sector had in the past proved deficient. Yet you, said Pierre Razoux, indicating in the general direction of the British participants, believe in the market while we believe in people. He told a story based 4 on his experience of working in the Ministry of Defence in Whitehall about the remarkable tolerance of his colleagues towards “hot-desking” – a symbol of how UK employers tend to treat their staffs as moveable and disposable. Myriam-Isabelle Ducrocq expressed her puzzlement at what she saw as under-funding of education and, especially, inadequate support for students entering higher education – though her remarks were rebutted by, among other, Jonathan Portes, who pointed to recent changes in policy and the Blair government’s commitment to expansion in student numbers. Pierre Razoux counselled against simplistic comparisons across the Channel. Political economy in the two countries was “path-dependent”: you could explain the shift in a liberal direction in the UK in the 1980s by reference to the financial crisis of the previous decade when the International Monetary Fund had to tender an emergency loan. Thus, the British model of public-private partnership was not going to be applicable in France where the private sector tended to enter public provision as a concessionnaire. And, said Isabelle Lescent-Giles, there’s differentiation between the two countries in their business cultures, one influenced by engineering and its emphasis on security and reliability, the other by finance – though the “MBA culture” was now spreading in France. Still, there were marked differences in conceptions of the public realm, Chantal Hughes remarked, some of them stemming from this divergence in the cultural weight of engineering in the two countries. Take nuclear power, where French policy and attitudes are remarkably different from the UK’s. Behind that (the point was made by Helene Masson and others) lay profound differences in conceptualisation of the state and its relationship to economy and civil society. The Jacobin tradition was by no means exhausted in France! How does this generation unite and divide on social/cultural questions That said, there was nothing fundamentally awry in Franco-British relations. Speakers, led by Yves Censi, lined up to endorse this view. The Francophile tradition in UK politics was long and deep. Its restitution depended only on political will – there to be mobilised and mustered. Conference co-chair Simon Atkinson backed this up with reference to polling data. But first he noted that French remains the first foreign language taught in English schools while trips across the Channel to France were hugely popular, at least among people living in the south 5 of England. Warm feelings about France were registered in surveys: the French are proverbial good at romance and food, though not necessarily in that order, while the British were perceived (by themselves at least) as good at television, sport and music. Older British people aspired to live in France and hundreds of thousands owned property there. Laurent Bonnard remarked that many tried living in France only to return home, finding life there wasn’t so idyllic. (put here MORI: Moving to the EU But an earlier remark by William Vereker about the UK possessing some strong attraction for younger French people was disputed. If, as he claimed some 250,000 French people aged between 25 and 35 lived London, as many British people of the same age lived in Paris, someone asserted. In one intervention, Jeannette Bougrab noted tartly that she was one of 60m who had chosen to remain in France. M Bonnard said images of each country were often anachronistic. People in Britain still thought of France in 1980s terms, along with trains a grande vitesse. Jeannette Bougrab urged participants to remember the differences that existed within the territory of the UK. In France state and language were co-eval while in the UK the state encompassed more than one nation and several languages. Participants from Scotland and Wales urged caution about grand, UK-wide references. John Edward recalled the Auld Alliance between Scotland and France before noting that Queen Elizabeth was not head of the established church in Scotland. (Put here MORI: Different aspects of Britain and France) James Tugendhat wondered if some of the debate about difference really reflected the modern experience of business where executives did move between countries. Archetypal French companies L’Oreal and Pernod Rickard were run by British managers. Perhaps the problem – this was to be picked up in the seminar’s recommendations for action – was the relative absence of exchange of staff in the sphere of politics and public administration. Seminar participants agreed that both countries faced similar fissures, over gender, employment and ethnic minorities. Public attitudes were not markedly different nor, allowing for institutional differences, were policy responses. What the seminar showed, however, is that the language and conceptualisation of questions of cohesion and integration are distinct on either side of the 6 Channel. French Thirtysomethings can muster a “republican” rhetoric similar to their elders. UK Thirtysomethings, like the generation before them, prefer a lower key, pragmatic approach to social integration, mixed with a slight, but typical, diffidence about definitions of Britishness. Raj Jethwa noted that unemployment among young workers from ethnic minorities in the UK was up to three times that of their white contemporaries. Young workers were pressured to attain in the education system, expected to move jobs: he wondered if things were much different in France. He noted that the pay gap between the genders had been growing in France as in the UK, suggesting that neither the French nor the British employment models were working especially well. Both left some groups marginalised and excluded. One failed to maximise security and the other left too many unemployed, said Sunder Katwala – was there a “third way” between them? The countries faced similar questions when it came to the balance between work, family life and leisure, said Laurence Laigo. Of course there were differences. She noted the large gap in labour productivity rates with the UK underscoring France by up to 25 per cent. Trade unions faced similar problems. Membership was in decline as the age profile of the workforce increased; in both countries unions needed to renew themselves while confronting globalisation. She extolled the way UK unions had integrated themselves into European institutions and welcomed the leadership of John Monks, director of the European Federation of Trade Unions Both France and the UK have substantial Muslim minorities and, on the evidence of this seminar, their condition, prospects and integration are matters of deep anxiety to Thirtysomethings even if, as we saw above, there is no straightforward generational take on solutions. British participants were puzzled at the agitation in France over recent months about appropriate wear at school and the law banning religious symbols. French participants were puzzled at what they feared was complacency on the British part about fundamentalism in their midst, contrasting as they saw it not just with France but with the Netherlands and Germany as well. Jeanette Bougrab focused attention on the French tradition of laicite, and the consistent, even severe, separation of the state from expressions of religious affiliation in public spaces. She sought to enlighten British participants about the debates that have been going on among French feminists, on the French left and 7 right on where tolerance and understanding should end and the assertion of universal values should begin. France had no official religion. The school, said Mathieu Flonneau, were not just educational institutions, they belonged to a broader, civic tradition, binding students into the state: they are ecoles de la republique. Differences of view between France and the UK could be mapped not just in regard to schooling – take your approach to monarchy or even to the regulation of gambling, he said. In the UK you allow things then regulate them; in France restrictions are imposed, but exemptions allowed. The policy question was integration. But did traditional models of assimilation apply any more? They were intact in neither country. Against them, said Jeannette Bougrab, ran a current of fundamentalism impacting on the school curriculum as on the gender mix in schools. Its eddies were visible on the streets of Amsterdam and in attempts to silence criticism of Islam as blasphemy. The object of policy must be co-existence, she said, but on the basis of certain values that were non-negotiable. Some of these values had to do with the position of women; she was worried that women had failed to protest at abuses in such countries as Iran. But there were other positions in the debate about whether Muslim girls should be permitted to wear headscarves and veils to school. Mathieu Flonneau noted a paradox of integration in France, that younger generations were finding it more practical to learn and use English, regardless of their ethnic background Don’t take women for granted, Laurence Laigo warned, they are not “an economic given”. Attention had to be paid to women’s sensibilities, especially now, at the 30th anniversary of the passage of the French abortion law. We share attitudes on migration and minorities, according to Simon Atkinson. In both France and the UK some two thirds of the population think the number of immigrants should be reduced. Those attitudes were closely linked to respondents’ sense of Britishness and Frenchness, and in no simple Front National/British National Party way. People wanted immigrants to be prepared to take on established customs and values. But what if – this point was made later in the seminar in discussions about the future of France and the UK in Europe – national identities were themselves in flux? Anwar Akhtar drew on his own experiences of growing up in an ethnic minority community, separated by race and religion from his white working class contemporaries. Social exclusion remains a fact of ethnic minority life and he warned of how fundamentalism exacerbated it. Leadership in some Bangladeshi communities in the UK was “feudal”. He described younger people dropping out of 8 school, unlettered and unknowing – they often had no conception of the Holocaust, he said, and became easy prey to reactionary preachers of religion. But engagement with some minorities had to begin overseas, Anwar Akhtar said: a new UK foreign policy was needed for Afghanistan and Iraq. Much could be done at home, with mentoring programmes and better integration in and of schools. The arts had a role, Fiona Laird asserted, in integrating communities. Language was however an issue. Addressing the possibilities of more fruitful British-French interchange, she worried about the reluctance of English speaking audiences to hear or see anything other than English in film or theatre. It was wrong to say British culture was not open but its penetration by contemporary European material, including drama from France, was slight. How does this generation unite and divide on Europe and transatlantic relations? As discussion turned to the future of Franco-British relations, twin questions were raised, about UK membership of the European Union on the one hand and French coming to terms with a changed EU on the other. Was there a generational colouring to this discussion? Perhaps Thirtysomethings from the UK are more fatalist about Europe than their elders. Not less committed nor any less convinced that the future of their country has to be “European”, but weary before their time about the possibilities of shifting opinion in the UK. As for their French contemporaries, the note struck at the seminar was more puzzlement: where would France fit in a EU with 25 members; would the fabled relationship across the Rhine just keep ticking over, taken for granted rather than celebrated; what on earth could they do about the behemoth across the Atlantic? Debate over Europe had migrated inside political parties in both parties, it was suggested. But where were the “big figures” to present new phenomena to a new generation that had no sense of Europe’s history? (put here MORI: Who are our friends? And Cultural identity) Nick Clegg, a former MEP, characterised differences between France and the UK this way. The Franco-German motor had made the construction of Europe an “entirely uplifting affirmation of peace”. For the British membership of the EU and its predecessors was merely an “unavoidable fate”. The genius of the EU had been its capacity to hold and sustain these different views. Could 9 that continue as the transatlantic relationship broke down, the potential entry of Turkey changed Europe in profound ways and some common security policy was hammered out? Could the institutions contain differences in the way they had? (Put here MORI: EU membership: good or bad?) Arnaud Leparmentier said Europe for the French had some of the characteristics of a battleground after a major defeat. “Their” Europe was a minority game. The UK had won the latest rounds. But, he quipped, while the British knew what they don’t want from Europe, the French don’t know what they do want. The strategy being pursued by President Jacques Chirac was opaque but what we and he knew was that in a Europe of 25 Tony Blair was going to find plenty of allies. Like Nick Clegg, he said the European Union had to come to terms with the “transatlantic model”, which he characterised as free exchange of goods and capital plus strong diplomatic ties to the United States. Other pressing issues were the admission of Turkey and the development of common EU institutions and common tax policies. As for the constitution (M Leparmentier said), the UK point man Peter Hain had networked well and made great gains in the face of declining French influence, compounded by French diplomats’ “arrogance”. But don’t both Blair and Chirac lack a strategy for Europe, asked Richard Whitman. Like Arnaud Leparmentier, he noted how the UK government had pretty much got what it wanted from the negotiations over the European constitution, though you would not think it from official reactions – no celebration at all. Perhaps that derived from a lack of self-confidence about where the UK finds itself. (Put here MORI: The EU must adopt a constitution) And that stemmed in large measure from the BritishAmerican connexion. “The disastrous US”, in Laurence Laigo’s phrase, outside good and evil, committing absolute error under President George W Bush. It has a different culture not least from the UK’s, she argued – those references to homosexuality and God’s place in political rhetoric were foreign. Not surprisingly, given the closeness of Prime Minister Tony Blair to President Bush, the UK minister David Miliband took a different tack. His theme was greater rather than less cooperation across the Atlantic. Together the EU and the United States constituted between 60 and 65 per cent of world GDP. Unless they worked 10 together they would both we worse off. The nearest he came to criticism of American policy was to say that the US needed a rule based international order. It needed “founding values” for such an order, as insurance against the day when it was no longer a superpower. But how was it to be persuaded to adhere to such rules? France, with the EU, needed to engage with the US, on Kyoto, on Israel-Palestine but it would only succeed if, first, it put its own house in order. By this Mr Miliband meant behaving itself in an exemplary fashion. Europe extolled its “soft power”, so why not reach out to Turkey to draw the country into the European value system. And meanwhile attend to those values, confronting racism and anti-semitism at home. It’s important not to exaggerate the post-Iraq war rifts, at least between France the UK, said Pierre Razoux. There had been divergences in the past, and comings together. He cited Suez in 1956, the invasion of the Falklands, action in the Balkans in the mid-1990s and the 1998 military accord at St Malo. Had Iraq had a Suezsize impact on Franco-British cooperation, he wondered? The object was European security policy, to which France and the UK separately and together were key. And the way to combine that with maintenance of the transatlantic relationship, according to Richard Whitman to focus UK and French military preparations on action was that the Americans cannot or will not undertake. Earlier Denis MacShane said, Iraq to one side, the time was ripe for a new era of cooperation between France and the UK on the “big European dossiers” as Britain was seen as a serious European player. But much of this debate was nugatory, participants pointed out, unless the UK came to terms with its European destiny. Franco-British relations were largely unintelligible outside the context of Britain in the EU. And that posed many problems. We both have problems with Europe, noted Isabelle Lescent-Giles – a tendency to label bad all the regulation that emanates from Brussels. In France, perhaps also in the UK, pro and anti European positions were now being taken up inside political parties. But more important, said Agnes Alexandre-Collier was connecting with public opinion, which meant confronting the press. We need, she said, to “change the discourse on Europe”. That cued much anguish and hand-wringing from UK participants. The pro-European movement in the UK was, in the words of Nick Clegg, beleaguered, dispersed and demoralised. No dramatic turnaround in the balance of European forces was likely. That was mainly because in the UK the press had taken upon itself the role not just of critic but of anti-European propagandist. In the face 11 of this media usurpation, the political class had given up its sovereignty. Chantal Hughes said the Blair government had clearly to say what it thought about Europe and stop this impression of the EU being a necessary evil. Even when the UK got what it wanted, it was presented merely as damage limitation. Some British participants demurred. John Eidinow noted that Brussels did interfere and annotated what he saw as some of the disadvantages of EU membership for the UK. Yet membership was the only game in town for the UK in James Tugendhat’s view: there was no mid-Atlantic future. He was optimistic. If the real cost of sundering the UK from Europe could be made transparent and pinned on the proponents of exit, they would crumble. The choice had to be crystallised. Anti-Europeans had nowhere to go and the UK would eventually have to find a positive way of expressing the project to its own citizens. Other participants endorsed this plea for clarity of debate about the nature of the UK’s future in Europe, in or out. Was it to remain an elite project or might ways be found to connect with the public at large? Anwar Akhtar said ordinary people in Leeds and Manchester needed to see if their interests would be damaged if the UK were outside the EU. It was going to be very, very tough for the pro-Europeans to balance the American agenda. Yet the UK and France were locked in a common destiny, said HE Gerard Ererra, the French ambassador to the UK, as he concluded the seminar. He reminded the meeting of the positive spirit of President Chirac’s recent visit to the UK and of the productive talks that had taken place between Chirac and Blair. The subject of the day’s conversations was “inexhaustible”; the texture and quality of Franco-British relations would help shape the success of the UK’s presidency of the European Union in 2005 and its turn in the chair of the G8. Both countries had in their different ways to throw off the “weight of the past”. History, he said, was a rich resource, but potentially also a hindrance to contemporary understanding. There was a tendency to validate “negative” conceptions of the past. He was certain such forums as this helped fill gaps in our knowledge of each other. What proposals can we make? Being a diplomat M Errera did not directly identify one agency that might be responsible for spreading misconception and misunderstanding but participants in the seminar were less reticent. If a tendentious version of history were being carried and imposed on modern 12 consciousness a powerful and malign agency was responsible, and it was the media. Especially the British newspaper press. As they summed up, participants asked what might be done to ensure television viewers and newspaper readers were given a fairer picture of France (in the UK) and the UK in France. Another theme in the conclusions was that both French and British socio-economic “models” had strengths, but both could learn from each other. Sunder Katwala said the UK could benefit from application of aspects of the European social model while the European Union needed to pick up the UK emphasis on jobs and growth. Participants were positive about ways forward, yet they ran into a paradox. One dominant theme was the need to talk more together, to spend more time in conversation, learning and addressing themes of mutual interest. This was expressed as an age-specific demand. Yet participants seemed aware that their concerns, about economy, society, culture, were not so different from their parents’ nor, one suspected, their children’s; there was no easilyidentifiable “age-cohort” dimension to Franco-British attitudes. As we went round the table asking participants for succinct suggestions about action to take, several talked about rectifying and enriching flows of (factual) information about Europe in the UK and, to a lesser extent about Europe and the UK in France. Among the suggestions: Promote exchanges between schools and universities (students and academics), Increase exchanges between government officials, especially the Quai D’Orsay. They need not be long periods of sojourn. Internships or similar might be built into the training of officials. Encourage exchanges between employees in the private sector. British ministers and officials should conduct open press conferences in Brussels and abandon the practice of excluding non-British journalists. This would help prevent “two-tier” presentations of decisions to UK and non UK audiences and, potentially, make the conduct of UK policy in the EU more honest The UK government should be urged to reconsider the plan to stop compulsory foreign language learning after the age of fourteen. . Some more truthful account of aspects of life in France and the UK should be produced for circulation 13 in the respective countries – perhaps in the form of a brochure verite Improved coverage of each country in each other’s media might result from exchanges of reporters and other press personnel A European arts and film council should be created to fund joint projects The Labour Party should hold its spring conference in Le Touquet A joint manual of Franco-British history should be compiled, similar to the existing Franco-German historical project. More forums should be created for conversation and mutual learning, for the press, politicians and parliamentarians. More television documentaries should be produced about life in each country The UK government should promote a public information campaign about Europe, focussing on areas of multilateral and (Franco-British) bilateral agreement The FBC should provide other opportunities for a similar group to meet and discuss more focused aspects of Franco-British relations such as minority cultures and the barriers to success or the work being done in both countries to close the gender gap. end 14