Tomás Ruiz

Interpersonal Commitments and the Travel/Activity Scheduling Process

Matthew J. Roorda

Assistant Professor, Department of Civil Engineering University of Toronto 35 St. George Street Toronto, Ontario, M5S 1A4, Canada Tel: (+1 416) 978-5976 Fax: (+1 416) 978-5054 Email: roordam@ecf.utoronto.ca

Tomás Ruiz

Assistant Professor, Transport Department School of Civil Engineering Technical University of Valencia Camino de Vera s/n 46022 Valencia, Spain Tel: (+34) 963877370 Fax: (+34) 963877370 Email: truizsa@tra.upv.es

Paper submitted to the 11 th World Conference on Transportation Research San Francisco, California, June 24-29 2007.

Roorda, M. J. and T. Ruiz 2

Abstract

This paper analyzes the influence of commitments to other people on an individual’s activity scheduling process. The data are from the CHASE survey, a computerized activity scheduling survey conducted on 270 households in the Greater Toronto Area. Comparisons between the attributes of activities done alone and those done with other people are made. Relationships between interpersonal commitments to children, household adults, and non-household adults and the planning horizon and rescheduling characteristics of activities are analyzed. The analysis in this paper shows that it is too simplistic too assume that the “skeleton schedule” consists of “mandatory” activities, such as work and school, only.

Roorda, M. J. and T. Ruiz 3

Introduction

The travel behaviour research community needs to better understand the full range of constraints that influence activity participation, activity scheduling, mode and location choice. Spatial and temporal constraints have received a fair amount of attention in the literature. Since it is only possible for a person to be in one place at one time, these constraints are based on the fairly straightforward logic of Hagerstrand’s space time prisms (Hagerstrand, 1970). Modal constraints are also based on a straightforward logic of vehicle availability, tour-level consistency, and transit access (see for example Roorda et al., 2006, Miller and Roorda, 2005). A perhaps more difficult research question is the extent to which interpersonal commitments and interactions influence individuals’ activity/travel choices. Some of the research into these impacts has included task allocation, joint activity participation and joint travel, vehicle allocation and ridesharing. What has been missing in the literature is research dealing with the influence of commitments to household members and other people on an individual’s activity scheduling process. Typically, the assumption is made that “mandatory” activities such as work and school form the “skeleton” schedule and that other activities are scheduled around these skeletal activities, planned at a later date/time (Arentze and Timmermans, 2004; Miller and Roorda, 2003). But it is reasonable to hypothesize that in many cases, activities that involve commitments to other people are equally if not more important as “anchor activities” than those mandatory activities, particularly the care of children and arrangements to drop-off or pick-up other people. Furthermore, it is entirely possible that the degree of both preplanning and permanence (i.e. the likelihood that an activity will be executed without modification or rescheduling) of activities involving commitments to others is higher than those

Roorda, M. J. and T. Ruiz 4 that are done only to fulfill individual needs and desires, and thus can influence the timing of activities planned later. This paper explores, empirically, the influences between household and non household members on the activity scheduling process using data from the first wave of the Travel Activity Panel Survey, conducted on an initial random sample of 270 households in Toronto, Canada 1 . The first wave of this survey was conducted using the CHASE © survey instrument, an interactive computer program that observed the schedule building process of multiple household members over a period of one week. From this data source the following were observed: all activities planned and/or executed over the course of 7 days, including their start time, duration, location, and mode of transport; other people that were involved in the activity, including children and adults, both within and outside of the household; when activities were originally planned; when planned activities were changed throughout the week, and the reasons for those changes; This small but very rich dataset is analyzed in this paper to elicit valuable information about the relationships between household members and how those relationships influence travel behaviour decisions, and to what extent they constrain the process of schedule building. This empirical analysis has potential to inform future modelling efforts by identifying the key constraining and influencing factors associated with interpersonal interactions that affect the activity scheduling process. In addition to the potential for improvement to activity scheduling models, this research is a necessary step towards more detailed and insightful analysis of a variety 1 A complementary survey was conducted in parallel in Quebec City, Canada, using similar survey design. The analysis in this paper, however, is limited to data from Toronto.

Roorda, M. J. and T. Ruiz 5 of policies. First, the activity schedules of children can be influenced through government policy in a variety of ways. School location, staggering of the start and end-time of school, bussing programs, and the setting of school jurisdictional boundaries can be assessed with regard to their impact on the schedules not only of children, but also the travel and activity behaviour of family members. Second, the success of policies aimed at improving opportunities for ridesharing/carpooling depends on the ability and willingness of potential carpoolers to manage the new constraints on their time. It is also important to understand interpersonal relationships in activity travel scheduling behaviour because of changing family, social, and demographic structure. Such trends may cause fundamental changes in travel patterns and mobility that need to be anticipated and accounted for in land-use transportation and infrastructure planning policy.

Literature Review

There is a growing body of literature describing the interactions between household members and their influence on activity travel patterns. The particular interactions of relevance include task allocation, joint activity participation and joint travel, and vehicle allocation and ridesharing.

Task Allocation

Most of the research to date in the area of task allocation has focused on household heads, and has tried to relate a variety of individual and household socio-economic and household structure variables to the choice of which household members undertake various household tasks.

Roorda, M. J. and T. Ruiz 6 Scott and Kanaroglou (2002) used data from a trip diary survey conducted in the Great Toronto Area to study interactions between household’s heads in taking decisions underlying the daily number of non-work, out-of-home activity episodes. Several significant interactions between household’s heads are identified. Moreover, the nature of these interactions is shown to vary by household’s type implying that decision-making structure and, more generally, household dynamics also vary by household type. For example, their results suggest that traditional gender roles persist only in couple, one-worker households. Srinivasan and Reddy (2005) investigated within-household and between household effects in maintenance activity allocation. They found that the head of the household is more likely to participate in maintenance activities than his/her spouse, especially if the household head is female. Children in the household are significantly less likely to perform maintenance activities. Household characteristics, such as the number of vehicles, income, presence of children, and employment were found to impact the allocation of household maintenance activities. Srinivasan and Bhat (2005) used 2000 Bay Area Travel Survey Data to study in-home and out-of-home maintenance daily activity generation of household heads, accommodating various household interactions effects. They found that the daily time investment of the husband and wife in household chores is significantly impacted by individual/household characteristics and the daily mandatory activity participation characteristics of the household’s heads. In the case of households without children, the husband’s out-of-home work duration determines the disparity between the time invested by the husband and the wife for household chores. In the case of households with children, the in-home maintenance time investments of both the husband and

Roorda, M. J. and T. Ruiz 7 wife are found to be influenced by their respective work duration as well as the work duration of their spouses. Ettema and van der Lippe (2006) investigated rhythms in spouses’ task allocation patterns and strategies on a weekly and day-to-day level using a 2001 data set of spouses’ time use. They found that the presence of young children in household increases the female’s share of household tasks and childcare, while lowering her share of paid work. Their analysis of variances and covariances in the allocation of work, household tasks and childcare suggests that a day-to-day specialization is indeed applied as a time management tool. Zhang et al. (2005) examined weekly variations on time allocation behavior within a household of married couples and found several differences in intra household interaction on weekdays versus weekends. In particular, the number of passenger cars available, the occurance of joint activities, and the extent to which activity patterns of husbands and wives could be considered “rational” was found to vary between weekends and weekdays.

Joint activity participation and joint travel

A parallel and often overlapping literature, deals explicitly with the choices associated with joint trips and activities. Srinivasan and Bhat (2005) found that grocery shopping during weekdays is most likely to be undertaken independently rather than jointly, and that women are generically more likely to undertake household’s shopping than men. Srinivasan and Reddy (2005) found that as the number of employed members increase, joint maintenance participation propensity decreases. It was observed that lower income households are more likely to participate in joint maintenance activities

Roorda, M. J. and T. Ruiz 8 than their medium a high-income counterparts. Similarly, a greater degree of joint activity participation was found in household with related members than households with unrelated individuals. Sivaramakrishnan and Bhat (2006) found evidence of the positive impact of vehicle availability on independent activity participation and the negative impacts of the presence of children and mandatory time investments on the joint discretionary activity engagement of the spouses. Chandrasekharan and Goulias (1999) used the Puget Sound Transportation Panel to study the propensity of people to make solo and joint trips. The analysis consists of trip-based models in which solo versus joint trip making is explained in terms of person and household sociodemographics, daily activity and travel patterns, dwelling unit and workplace level of service and land use characteristics, and trip attributes. The analysis is repeated for all the days and all the waves (years) of the panel at hand. The analysis reveals that the major factor that determines joint trip making is the life-cycle stage of the household. It is also observed consistently across all the waves that, as the age of the person increases, the number of joint trips he or she makes also increases. Other factors that consistently affect joint trip making are household size, age of the household members, number of vehicles in the household, daily activity and travel patterns, and certain accessibility measures such as the access from transit to auto. Gliebe and Koppelman (2005) analyzed joint activity patterns of pairs of household decision makers as the subject of analysis using household survey data. They found that the utility of making fully joint tours is higher for households with two retired adults, and for households with fewer cars than workers. In contrast, households in which at least one adult is a student show a significant negative

Roorda, M. J. and T. Ruiz 9 propensity to engage in fully joint tours. The total number of children in the household has a significant negative effect on the utility of fully joint home-based tours (between adults). Both very young and older children have a significant negative effect on the propensity of theirs parents to choose shared ride arrangements. They found that in making joint activity-travel decisions significantly greater emphasis is placed on the individual utilities of workers relative to non-workers and on the utilities of women in households with very young children. Bradley and Vovsha (2005) propose a model for joint choice of daily activity pattern types for all household members that explicitly takes into account added group-wise utilities of joint participation in the same activity. The model is based on the aggregate description of individual daily activity pattern types by three main categories – mandatory travel pattern, non-mandatory travel pattern, and at-home pattern. At this aggregate level, the model estimation confirms a strong added utility of joint choice of the same pattern for such person types as non-worker or part time worker in combination with child, two retired persons, two children, and others. They found statistically significant interactions between pairs and triads of households members, indicating that members of various types are prone to change their activities to match those of other household members. Miller and Roorda (2003) developed the Travel Activity Scheduler for Household Agents (TASHA) which simultaneously generates activity schedules for multiple household members, including the generation of joint activities, and have conducted a preliminary validation of the model for forecasting purposes (Roorda et al., 2007). This model assumes that joint non-work/school activities are scheduled after work/school activities, but before individual non-work/school activities.

Roorda, M. J. and T. Ruiz 10

Vehicle allocation, ridesharing, trip chaining and mode choice

Some recent research has focused on household interactions of vehicle allocation, ridesharing, trip-chaining and mode choice, and the extent to which these phenomena are driven by interactions within the household. Kuhnimhof et al. (2006) used 7-day-trip-diary data from the German Mobility Panel to study individual mode choice behavior. They found that the presence of children and other adults in households increases the probability that adults in the household drive. In particular they found that the presence of children in a household reduces the probability of using public transport for purposes other than commuting. Morency (2006) analyzed ridesharing in a series of large scale OD surveys in Montreal, Canada. This study found that 70% of all trips made by car passengers are the result of intra-household ridesharing, and the 15% of these trips were exclusively generated for another individual’s purposes, consequently generating an additional trip for the journey back home Vovsha and Petersen (2005) studied joint travel arrangements that arise when adult household members escort children to school. They found that preschool children require escorting more frequently, followed by school children of pre-driving age. All else being equal, female household members performed the escorting function more frequently than males. Part-time workers and non-workers are more frequently involved in pure escorting while full-time workers are more frequently involved in ride-sharing arrangements. Household interactions have been found to influence trip chaining. Noland (2006) used the 2001 National Household Travel Survey to analyze trip chaining and found that single adults, and especially single parents are more likely to link trips and

Roorda, M. J. and T. Ruiz 11 make more complex tours. Families with a more traditional structure (two or more adults with a child aged at least 6-15) make less complex tours. Richardson (2006) found that the number of trips per person per day decreases as the average age of the household grows. Individuals living with younger people present a greater number of trips per day than those living with same age people. And the latter present a greater number of trips per day than those living with older people. Roorda et al. (2006) estimated a tour-based random utility mode choice model that explicitly incorporates vehicle allocation, ridesharing to joint activities and chauffeuring (dropping off/picking up family members). This analysis demonstrated that it is feasible to explicitly represent the negotiations associated with sharing household vehicles and matching multiple household members’ activity patterns to allow for ridesharing opportunities. The activity patterns, generated by the Travel Activity Scheduler for Household Agents (TASHA) formed the activity pattern inputs to this model including joint household activities. The analysis found that much of the mode choice behaviour of individuals in a household can be explained by the constraints imposed by other household members, resulting in less importance associated with socio-demographic model variables. The emphasis in the majority of these studies is to describe the influence of household structure and demographic variables on the types of household interactions that occur. There is need for more focused research into the degree to which household interactions explicitly influence the formation of activity and travel patterns.

Roorda, M. J. and T. Ruiz 12

Data

The Travel Activity Panel Survey (TAPS) is an in-depth longitudinal survey of activity and travel scheduling processes, undertaken on a sample of 270 households in Toronto and 250 households in Quebec City, Canada (Roorda et al., 2005, Roorda and Miller, 2004). The TAPS survey consisted of three waves in each of the two geographic locations, each wave using a different survey instrument. In Toronto, the first wave was conducted between March 2002 and May 2003 using the CHASE © survey instrument (Doherty and Miller, 2000; Doherty et al., 2004). CHASE is a computerized activity scheduling survey that is completed by multiple household members, with the purpose of obtaining detailed information about the planning, scheduling and execution of activity schedules over a seven-day period. Participating households are provided with a laptop with the CHASE software and, after an initial interview and training session at the outset of the seven-day period, are asked to maintain a computerized diary of all activities that are planned (scheduled), how those planned change or are elaborated in more detail over the course of the week, and how those plans are executed. This survey procedure is one of very few successful methods for observing the process of activity scheduling. Numerous attributes of the activities are gathered in the CHASE survey. Figure 1 shows the screen in which respondents recorded the basic attributes of new activities that were added to the activity schedule. In addition to the activity type, location, mode(s) and timing, respondents were also asked to enter information about the children that were under their care while doing the activity and any other people that were directly involved with the respondent in the activity. The respondent chose individuals from drop-down lists pre-defined by the respondent during the pre-survey interview as those that would likely be involved for at least one activity over the

Roorda, M. J. and T. Ruiz course of the week. However, “new” involved persons, not pre-defined at the outset could be added to the list using special “pop-up” boxes. 13

Figure 1 – Basic information collected for each added activity

For each activity entered before it was executed, the CHASE survey asked:

“When did you originally make the decision to add this activity? (i.e. at what point were you relatively sure about when where and with whom this activity would take place)”

Roorda, M. J. and T. Ruiz 14 The resulting responses were coded into the following general categories (although more detail is available, as discussed by Doherty, 2005): Spontaneous Planned on the same day Planned weeks / months / years ago Routine Unknown / Can’t Recall / Missing The purpose of this question was to ascertain the types of activities that form the “skeleton” of the schedule, or in other words, the part of the schedule that is routine or planned in advance, and which therefore forms the spatio-temporal structure around which other more spontaneously planned activities are scheduled. The CHASE survey also recorded any activity additions, modifications or deletions that are made to the schedule over the course of the week. Thus, it is possible with this data set to compare the attributes of activities that are executed as originally planned to those that are modified. This has the potential to provide an indication of the degree of permanence associated with activities entered into the schedule. The purpose of the analysis in this paper is to explore the association of interpersonal commitments with the degree of preplanning associated with those activities and the degree of permanence associated with those activities, once they are entered into the activity schedule.

Analysis

Number and duration of activities by commitment

Roorda, M. J. and T. Ruiz 15 Table 1 shows that, of the total number of activities that CHASE respondents engaged in, the majority are reported to have been done alone (71%), including both in-home activities (75.1%) and out of home activities (58.5%). The remaining activities are either done with child members (9.1%), with adult members (7.5%) or with non-household members (8.4%), but are rarely done with combinations of these groups (3.8% for the total of all combinations). For the sake of simplicity and clarity, the analysis in this paper focuses on those activities that are done either alone, with children or with others from within or outside of the household, but not with combinations of these groups. The pattern for activity duration is similar, but shows that even a greater proportion of time is spent doing activities alone (77.5%). Table 2 shows that activities done with non-household members are far more likely to be done out-of home (59% of the number and 67% of the duration) than activities done alone (20%) or with household members (ranging from 21% to 35.6%). This is a natural and expected result, it is clear that those who share a home are more likely to engage in activities together within that home. The duration of activities also appears to be related to the location of and the people involved in the activity. Out of home activities done alone have a longer mean duration (178 min) than in-home activities done alone (113 min). Similarly, out-of-home activities done with non-household members have longer duration than in-home activities (126 min to 89.7). Conversely, activities done with children or adults within the household are of longer mean duration within the home (68.4 and 100.0 minutes), than out-of-home activities with these groups (49.6 and 87.7 minutes).

Roorda, M. J. and T. Ruiz

Table 1 - Number and Duration of Executed Activities by Involved Persons 1

Involved Persons Alone With Child Household Members With Adults Household Members With Non-Household Members With Adult & Children Household Members With Adult & Non-Household Members With Children & Non-Household Members With Adult, Children and Non-Household Members Total Total Activities Number (%) Duration (%) 24350 71.0% 3076375 77.5% 3126 9.1% 199865 5.0% 2573 2895 7.5% 8.4% 250491 322052 6.3% 8.1% 623 322 313 1.8% 0.9% 0.9% 44993 38096 29905 77 0.2% 8428 34279 100% 3970205 1.1% 1.0% 0.8% 0.2% 100% Out of Home Activities Number (%) Duration (%) 4882 748 548 1698 9.0% 6.6% 37103 48055 3.0% 3.9% 20.4% 214624 17.6% In-Home Activities Number (%) 2378 2025 1197 9.2% 7.8% 4.6% Duration (%) 58.5% 870116 71.3% 19468 75.1% 2206259 80.3% 162762 202436 107428 5.9% 7.4% 3.9% 222 95 118 31 8342 2.7% 1.1% 1.4% 16467 17484 12102 1.3% 1.4% 1.0% 401 227 195 1.5% 0.9% 0.8% 28526 20612 17803 1.0% 0.7% 0.6% 0.4% 5063 0.4% 46 0.2% 3365 0.1% 100% 1221014 100% 25937 100% 2749191 100% 1 – Night sleep activities are assumed to be done alone. Given the sensitive nature of the question, respondents were instructed to leave the “involved others” fields blank for night sleep activities.

Table 2 – Comparison of Location and Mean Duration of Executed Activities

Involved Persons Alone With Child Household Members With Adults Household Members With Non-Household Members With Adult & Children Household Members With Adult & Non-Household Members With Children & Non-Household Members With Adult, Children and Non-Household Members Total % out of home Number 20.0% 23.9% 21.3% Duration 28.3% 18.6% 19.2% 58.7% 35.6% 29.5% 37.7% 40.3% 24.3% 66.6% 36.6% 45.9% 40.5% 60.1% 30.8% Total 126.3

63.9

97.4

Mean Duration (min) Out-of-home 178.2

49.6

87.7

In-home 113.3

68.4

100.0

111.2

72.2

118.3

95.5

109.5

115.8

126.4

74.2

184.0

102.6

163.3

146.4

89.7

71.1

90.8

91.3

73.2

106.0

16

Roorda, M. J. and T. Ruiz 17

Activities by Type and Commitment

Part of the difference in the mean duration of in-home and out-of-home activities for activities involving different people is the nature of the activities that are undertaken. Figure 2 shows the proportion of the duration of out-of home activities of different types engaged in alone, with children, with household members and with non-household members. Clearly the types of activities done with these different groups of people vary quite dramatically. Out-of-home activities done alone are dominated by work/school activities, which make up almost 80% of the total duration of out-of home activities done alone. If children are under the care of the respondent during the activity, the greatest time is spent on household maintenance activities (47%), recreation/entertainment (22%) and social activities (17%). Non-household members are most likely to spend time with respondents in social (28%), recreation/entertainment (21%) or work/school activities (28%). Activity time spent with household adults, in general, falls proportionally between that of activities with children and activities with non-household adults for almost all activity types. In short, time is spent on very different activities, depending on who is involved. The proportions can also be analyzed in terms of the numbers of activities, which shows a similar pattern to that of the proportions based on activity duration. The major difference in Figure 3, as compared to Figure 2, is the increased prominence of household maintenance activities, and the decreased prominence of work/school activities. This is

Roorda, M. J. and T. Ruiz 18 because the mean duration of work/school activities is much longer (320 min) than that of household maintenance activities (43 min). Given the prominence of the number of household maintenance activities for activities involving multiple people, it is important to note that there is significant diversity within the household maintenance category, as shown in Figure 4, depending on what types of people are involved. Out-of-home household maintenance activities are dominated by drop off/pickup of people, if other people are involved in the activity. Close to 3/4 of all household maintenance activities performed with children are to pick up/drop-off people (most likely the children themselves), which shows a clear chauffeuring phenomenon. Non grocery shopping is the second largest component of household maintenance activities and this category is of greatest prominence among household maintenance activities done alone and those involving non-household members.

Roorda, M. J. and T. Ruiz

Proportion of Duration of Out of Home Activities by Type and Commitment

90.0% 80.0% 70.0% 60.0% 50.0% 40.0% 30.0% 20.0% 10.0% 0.0% B as ic N ee ds W or H k ou S ch se oo ho ld l M R ai ec nt re en at an io ce n En te rta in m en t S oc ia l O th er No others or children Children Only Others In Household Only Non hhld Others Only

Figure 2 – Proportion of Duration of Activities by Type and Commitment Proportion of Number of Out of Home Activities by Type and Commitment

19 80.0% 70.0% 60.0% 50.0% 40.0% 30.0% 20.0% 10.0% 0.0% B as ic N ee ds W or H k ou S se ch oo ho ld l M R ai ec nt re en at an io n ce En te rta in m en t S oc ia l O th er No others or children Children Only Others In Household Only Non hhld Others Only

Figure 3 - Proportion of Number of Activities by Type and Commitment

Roorda, M. J. and T. Ruiz

Out of Home Household Maintenance Activities Done Alone Out of Home Household Maintenance Activities Done with Others In Household

20

Out of Home Household Maintenance Activities Done with Children Out of Home Household Maintenance Activities Donewith Non-Household Members

Household Obligations Pickup/dropoff People pick up dropoff other items shopping convenience and minor grocery (<10 items) Major groceries (10+ items) other shopping Medical/professional Banking Religious other

Figure 4 – Out of Home Household Maintenance Activities by Commitment

Planning Horizon of Activities by Commitment Activities done alone have different planning horizons than those done with other people. As shown in Figure 5, over 60% of time spent on out-of-home activities done alone, is planned at least one week in advance. This is compared with a proportion of less than 40% of time spent on out-of-home activities done with other people. This would appear to indicate that the skeleton schedule consists mostly of those activities done alone.

Roorda, M. J. and T. Ruiz 21 However, the difference is not visible in Figure 6, which shows the proportion of the number of activities, rather than the duration of activities. Clearly, the high duration of out-of-home activities done alone is largely due to the influence of work/school activities, which make up almost 80% of out-of home activities done alone. So, while work/school activities do make up a the largest proportion of preplanned activities by duration, it is by no means clear that the preplanned skeleton schedule involves only “mandatory” work/school activities, as most modeling efforts assume.

Proportion of Out of Home Activity Duration by Planning Horizon and Commitment

70.0% 60.0% 50.0% 40.0% 30.0% 20.0% 10.0% 0.0% No others or children Children Only Others In Household Only Non hhld Others Only Same day days before long planned

Figure 5 – Proportion of the Duration of Out-of-Home Activities by Planning Horizon and Commitment

Roorda, M. J. and T. Ruiz 22

Proportion of Number of Out of Home Activities by Planning Horizon and Commitment

60.0% 50.0% 40.0% 30.0% 20.0% 10.0% 0.0% No others or children Children Only Others In Household Only Non hhld Others Only Same day days before long planned

Figure 6 – Proportion of the Number of Out-of-Home Activities by Planning

Horizon and Commitment A remaining question is whether greater heterogeneity in the planning horizon of activities can be observed when disaggregated by both activity type and by the commitment with other people. Figure 7 shows the frequency of out-of-home activities by planning horizon and by activity type. As expected, the most common out-of-home activity done alone is work/school and these activities are most often preplanned. The other significant activities done alone are household maintenance activities, which are usually planned on the same day. A very different pattern emerges for activities done with children. These activities mostly consist of household maintenance activities (usually dropping-off and picking-up). Drop-off / pick-up activities are most frequently preplanned at least one week ago. Aside from household maintenance activities, the most common activities done with children are recreation / entertainment, and these activities are usually planned on the same day. Activities done with adults, either living in the

Roorda, M. J. and T. Ruiz 23 household or not, are somewhat more diverse and cover a greater variety of activity types and planned at a greater variety of different horizons. So, although Figure 6 appears to show homogenous activity planning horizons for activities with different interpersonal commitments, Figure 7 shows underlying heterogeneity in the types and planning horizons of activities that are performed alone or with different groups of people.

Out Of Home Activities Done Alone Out of Home Activities Done With Others In Household

1400 1200 1000 800 600 400 200 0 Basic Needs Work School Hhld Maint Rec Enter.

Social Other Preplanned Days Before Same Day

Out of Home Activities Done With Children

160 140 120 100 80 60 40 20 0 Basic Needs Work School Hhld Maint Rec Enter.

Social Other Preplanned Days Before Same Day

Out of Home Activities Done With Non-Household Members

300 250 200 150 100 50 0 Basic Needs Work School Hhld Maint Rec Enter.

Social Other Preplanned Days Before Same Day 250 200 150 100 50 0 Basic Needs Work Schoo l Hhld Maint Rec Enter. Social Other Preplanned Days Before Same Day

Figure 7 – Number of Out-Of-Home Activities – by Activity Type and Planning Horizon

Roorda, M. J. and T. Ruiz 24

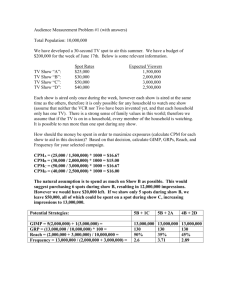

Rescheduling of Activities

A central question is to what extent activities that involve commitments to other people are modified or deleted in response to new opportunities or constraints. The CHASE survey allows for an analysis of this phenomenon because respondents are asked to record any changes that arise in their plans over the course of the seven-day survey period. Activities are either executed as planned, are modified, or are deleted entirely. In some cases (those indicated as other), a more complicated set of operations resulted in the activity not being executed as originally planned, but could not be clearly identified either as a modification or a deletion. Figure 8 shows the breakdown of the duration of planned activities in terms of whether they were executed and modified or deleted. Clearly, activities that are done alone are less likely to be executed as originally planned than are activities that involve other people. These activities are most likely to be modified (13.6%) and have a 2.0% likelihood of being deleted. Those activities that involve children stand the greatest chance of being deleted (4.1%), but a relatively small chance of being modified (8.0%). Activities that involve other household members (but not children) are those that are most likely (89.0%) to be executed without modification, and these activities only have a slim (0.8%) probability of being deleted entirely. A very similar pattern is evident by looking at the proportion of durations of activities that are executed, modified or deleted. However, by duration the differences are more pronounced, because modified activities done alone are more likely to be of greater duration.

Roorda, M. J. and T. Ruiz 25

Proportion of OOH Activities executed modified deleted by Commitment - Number of Activities

100.0% 95.0% 90.0% 85.0% 80.0% 75.0% 70.0% No o thers o r children Children Only Others In Ho useho ld Only No n hhld Others Only Children and Others in hhld Other in and o ut o f hhld Children and o thers o ut o f hhld Chilren and o ther in and o ut o f hhld

Com m itm ent

Other Deleted Modified Executed

Figure 8 – Activity Rescheduling by Commitment – Proportion of Number of Out of-home Activities

Roorda, M. J. and T. Ruiz 26

Figure 9 – Activity Rescheduling by Commitment – Proportion of Duration of Out of-home Activities

Table 3 breaks this result down by planning horizon to show that: The activities most likely to be executed “as is” are those with children and planned on the same day, and those with others in the household planned on the same day, or part of the regular routine. The activities most likely to be modified are preplanned activities done alone or with others from out of home. The activities most likely to be deleted outright are preplanned activities with children or with others from out of the home.

Roorda, M. J. and T. Ruiz 27

Table 3 – Proportion of the number of activities, by planning horizon, by rescheduling, and by interpersonal commitment

Planning Horizon Spontaneous Planned on the same day Planned days before Planned weeks/mths/yrs ago Routine Unknown/can't recall/missing Total Activities Done Alone With Childern Originally Planned 1365 943 852 1232 687 868 5947 Executed 87.5% 90.9% 80.9% 76.3% 82.2% 73.4% Deleted 0.5% 0.4% 3.1% 3.7% 1.2% 3.2% Modified 10.4% 7.2% 13.4% 17.6% 13.8% 19.7% Other 1.6% 1.5% 2.7% 2.4% 2.8% 3.7% Originally Planned 172 150 153 224 82 89 Executed 86.6% 94.7% 81.0% 83.9% 86.6% 83.1% Deleted 0.6% 0.0% 5.2% 8.9% 2.4% 5.6% 82.1% 2.0% 13.6% 2.4% 870 86.0% 4.1% Categories that are > 3% above the mean proportion over all out-of-home activities Categories that are > 3% below the mean proportion over all out-of-home activities Modified 10.5% 4.7% 11.1% 5.8% 8.5% 9.0% 8.0% Other 2.3% 0.7% 2.6% 1.3% 2.4% 2.2% 1.8% With others in home Originally Planned 195 97 100 66 84 74 616 Executed 89.2% 92.8% 86.0% 89.4% 92.9% 82.4% 89.0% Deleted 0.0% 1.0% 0.0% 1.5% 0.0% 4.1% 0.8% Modified 8.2% 6.2% 11.0% 7.6% 7.1% 10.8% 8.4% Other 2.6% 0.0% 3.0% 1.5% 0.0% 2.7% 1.8% With others from out of home Originally Planned 520 380 413 214 203 277 2007 Executed 90.2% 90.8% 83.1% 80.4% 86.7% 69.7% 84.6% Deleted 0.6% 0.3% 1.9% 4.7% 0.0% 5.8% 1.9% Modified 7.3% 7.9% 12.6% 13.1% 10.3% 20.6% 11.3% Other 1.9% 1.1% 2.4% 1.9% 3.0% 4.0% 2.2%

Roorda, M. J. and T. Ruiz 28

Conclusions

Clearly, the analysis in this paper shows that it is too simplistic too assume that the “skeleton schedule” consists of “mandatory” activities, such as work and school, only. First, the types, locations, and durations of activities that involve other people or that are done alone have been characterized in some detail. In general, The majority of activities, both in-home and out-of-home, are done alone and less than 4% are done with combinations of children, adults from within the home and non-household adults The greatest proportion of activities done alone are work/school, whereas the greatest proportion of activities done with child and other household members are household maintenance activities, the activities done with non-household members are more evenly spread among several activity types. Second, the degree of preplanning associated with activities with different interpersonal commitments have been explored. Major findings are: While work/school activities do make up a the largest proportion of preplanned activities by duration, it is by no means clear that the preplanned skeleton schedule involves only “mandatory” work/school activities, as most modeling efforts assume.

Roorda, M. J. and T. Ruiz There is an underlying heterogeneity in the types and planning horizons of activities that are performed alone or with different groups of people. Finally, the likelihood with which activities involving different interpersonal commitments will be rescheduling has been analyzed (or in other words, the degree of “permanence” associated with planned activities). Activities that are done alone are less likely to be executed as originally planned than are activities that involve other people The activities most likely to be executed “as is” are those with children and planned on the same day, and those with others in the household planned on the same day, or part of the regular routine. The activities most likely to be modified are preplanned activities done alone or with others from out of home. The activities most likely to be deleted outright are preplanned activities with children or with others from out of the home.

Future Work

This preliminary empirical investigation sets the stage for more in-depth analysis and modeling. In particular, given the attributes of a planned activity, we can develop a model of the probability that a planned activity will be modified or deleted. Such a 29

Roorda, M. J. and T. Ruiz 30 model can be used to improve the behavioural validity of currently operational activity scheduling models such as TASHA. We can analyze trends over time in behaviour involving interpersonal commitments, joint activities, and joint travel. This can be done using repeated cross-section travel diary surveys in Toronto. Through such analysis, the implications of demographic trends, such as the aging population, changing spatial distribution of social networks, and locational patterns of households can be tested. Finally, policies such as school location, bussing programs, land use policy can be assessed as to their impact on the schedules, travel and activity behaviour of family members, in addition to the direct target population of each policy.

References

Arentze, T.A. and Timmermans, H.J.P. (2004) ‘A learning based transportation oriented simulation system’, Transportation Research B, 38, pp. 613-633. Bradley, M. and Vovsha, P. (2005) ‘A model for joint choice of daily activity pattern types of household members’, Transportation, 32(5), pp 545-571.

Roorda, M. J. and T. Ruiz 31 Chandrasekharan, B. and Goulias, K. G. (1999) ‘Exploratory longitudinal analysis of solo and joint trip making using the Puget Sound Transportation Panel’, Transportation Research Record, 1676. Doherty, S. T. (2005) ‘How far in advance are activities planned? Measurement challenges and analysis. Transportation Research Record: Journal of the Transportation Research Board, 1926, pp. 41-49. Doherty, S. T. and Miller, E. J. (2000) ‘A computerized household activity scheduling survey’, Transportation, 27(1), 75-97. Doherty, S.T., Nemeth, E., Roorda M.J. and Miller, E.J. (2004) ‘Design and assessment of the Toronto Area Computerized Household Activity Scheduling Survey’, Transportation Research Record, 1894, pp. 140-149. Ettema, D. and van der Lippe, T. (2006) ‘Weekly rhythms in task and time allocation of households’, Paper presented at the 85th annual conference of the Transportation Research Board, Washington, D.C., January. Gliebe J. P. and Koppelman, F.S. (2005) ‘Modeling household activity–travel interactions as parallel constrained choices’, Transportation, 32(5), pp. 449-471.

Roorda, M. J. and T. Ruiz 32 Hagerstrand, T. (1970) ‘What about people in regional science?’, Papers of the Regional Science Association, 24, pp. 7-21. Kuhnimhof, T., Chlond, B. and von der Ruhren, S. (2006) ‘The users of transport modes and multimodal travel behavior. Steps towards understanding travelers’ options and choices’, Paper presented at the 85th annual conference of the Transportation Research Board, Washington, D.C., January. Miller, E.J. and Roorda, M.J. (2003) ‘A prototype model of 24-hour household activity scheduling for the Toronto Area’, Transportation Research Record, 1831, pp. 114-121. Miller, E.J., Roorda M.J. and Carrasco, J.A. (2005) ‘A tour-based model of travel mode choice’, Transportation, 32(4), pp 399-422. Morency, C. (2006) ‘The ambivalence of ridesharing’, Transportation, published online. Noland, R. (2006) ‘Multivariate analysis of trip-chaining behavior’, Paper presented at the 85th annual conference of the Transportation Research Board, Washington, D.C., January. Richardson, A.J. (2006) ‘Alternative measure of household structure and stage in life cicle for transport modeling’, Paper presented at the 85th annual conference of the Transportation Research Board, Washington, D.C., January.

Roorda, M. J. and T. Ruiz 33 Roorda, M. J., Lee-Gosselin, M., Doherty, S. T., Miller, E.J. and Rondier, P. (2005) ‘Travel/activity panel surveys in the Toronto and Quebec City regions: Comparison of methods and preliminary results’, CD Proceedings of the PROCESSUS Second International Colloquium on the Behavioural Foundations of Integrated Land-use and Transportation Models: Frameworks, Models and Applications. Toronto, June. Roorda, M.J., and Miller, E.J. (2004) ‘Toronto Activity Panel Survey: demonstrating the benefits of a multiple instrument panel survey’, Paper presented at the Seventh International Conference on Travel Survey Methods. Costa Rica, August. Roorda, M.J., Miller, E.J. and Habib, K. (2007) ‘Validation of TASHA: A 24-hour activity scheduling microsimulation model. Paper presented at the 86 th Annual Meeting of the Transportation Research Board Washington, DC, January. Roorda, M.J., Miller, E.J. and Kruchten, N. (2006) ‘Incorporating within-household interactions into a mode choice model using a genetic algorithm for parameter estimation. Forthcoming in Transportation Research Record. Scott, D.M. and Kanaroglou, P.S. (2002) ‘An activity-episode generation model that captures interactions between households heads: development and empirical analysis’, Transportation Research Part B, 36, pp. 875-896.

Roorda, M. J. and T. Ruiz 34 Sivaramakrishnan S. and Bhat C. R.(2006) ‘A multiple discrete-continuous model for independent- and joint-discretionary-activity participation decisions’, Transportation,33(5), pp. 497-515. Srinivasan, K. and Reddy, S. (2005) ‘Analysis of within-household effects and between household differences in maintenance activity allocation’, Paper presented at the 84th Annual Conference of the Transportation Research Board, Washington, D.C., January. Srinivasan, S. and Bhat, C.R. (2005) ‘Modeling household interactions in daily in-home and out-of-home maintenance activity participation’, Paper presented at the 84th annual conference of the Transportation Research Board, Washington, D.C., January. Vovsha, P. and Petersen, E. (2005) ‘Escorting children to school: statistical analysis and applied modeling approach’, Paper presented at the 85th annual conference of the Transportation Research Board, Washington, D.C., January. Zhang, J., Timmermans, H., and Borgers, A. (2005) ‘Comparative analysis of married couples’ task and time allocation behaviour on weekdays vs. weekends’, Paper presented at the 84th annual conference of the Transportation Research Board, Washington, D.C., January.