The Effect of Higher Education of Graduate Outcomes:

advertisement

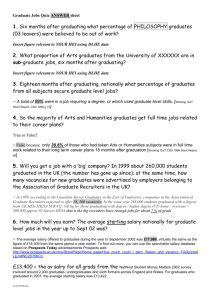

Human Capital Acquisition and Labour Market Outcomes in UK Higher Education: Summary of findings from CCMS funded PhD research Conducted by Dr Sarah Jewell This document provides an overview of the findings from one of two PhD studentships funded by the Centre for Career Management Skills (CCMS). The PhD student was Sarah Jewell, supervised by Dr Zella King and Dr Alessandra Faggian. The PhD commenced in September 2005, and was completed in October 2008. Overview of research approach The primary aims of the study were threefold: To identify the determinants of degree performance, taking into account a broad range of personal characteristics, as well as the effect of degree subject To examine the extent to which students are employed whilst at university, and its effect on their degree performance To analyse the combined effect of personal characteristics, employment at university and degree performance on outcomes in the labour market. The research was conducted using data from cohorts of University of Reading students graduating in 2006 and 2007. Data were collected from three main sources: the University of Reading student database (RISIS), a survey of Reading undergraduates circulated in spring 2006, and the destinations of leavers in higher education (DLHE) survey. The survey collected information on family and socio-economic background, financial situation, term time and vacation employment and attitudes to careers, enabling us to investigate a wide range of factors affecting degree performance and labour market outcomes, and to evaluate which factors are most important. To investigate the determinants of degree performance we used data from the 2006 and 2007 cohorts of Reading graduates (data on 4,577 students derived from RISIS) with additional insights derived from questions on the survey (completed by 678 students within the cohorts graduating in 2006 and 2007). The survey data permitted us to examine the incidence and reasons for employment, and its effects on degree performance. To analyse outcomes in the labour market, we combined data from RISIS with DLHE data for 2006 and 2007 British domiciled graduates (a total of 3,229 graduates), focussing on destinations, quality of graduate employment and salaries. 1. The Main Determinants of Degree Performance Personal characteristics and socio-economic background On average women tend to perform as well as or better than men in all subjects. There is a wider variation in male performance, with men more likely to get lower seconds and below There is some evidence that women are more likely to get a first than men in certain male dominated subjects, such as systems and software engineering, mathematics, meteorology and physics 1 Older students on average perform better but there is greater variation in their performance There is greater variation in the performance of overseas students – with differences across nationalities There were few socio-economic class effects. The only significant result was that males from non-professional background were more likely to gain a third or below than those from professional backgrounds Qualifications on entry to higher education (as measured by UCAS point score) and type of qualification are a strong predictor of degree performance. Those with higher UCAS scores get better degrees, and this is a very powerful factor On a like for like basis those who attended an independent school perform worse, particularly in terms of getting a first and especially for men Degree attributes There are more firsts awarded in science subjects particularly in biology and software and systems engineering. At the same time more thirds are awarded in sciences particularly in maths, meteorology and physics, construction management and engineering. Modern languages and business degrees have lower odds of a first or upper second, whilst law has the highest probability of a lower second There are variations across subjects in the strength of the relationship between UCAS points and degree performance, with strong correlations for agriculture, mathematics, meteorology and physics, business and biology. Weaker correlations exist for art, communication and design, law, politics and sociology Students who undertaken a four year course e.g. with a placement year or year abroad did better in their degrees than those on three year courses Additional insights from the survey responses No evidence that socio-economic background, parents’ education and financial situation (having family support, loans or scholarships) have a direct impact on degree performance Students who reported that career was very important to them (relative to other life roles) were more likely to get a first 2. The extent and effects of term time employment The extent and frequency of term time employment 14% of respondents to the survey had done some work experience as part of their degree. (Only 3% actually did a placement year.) 26% had undertaken some form of unpaid work experience 83% worked during vacations and 53% undertook term time employment at some point during their degree The majority of employed students worked for seven or more weeks per term in the years they work 2 36%-45% (depending on the year of study) of employed students work on average 11-16 hours per week, with 15-20% working more than the university limit of 16 hours There is an overall pattern that a greater proportion of students work with a greater intensity (where intensity is average weeks worked times average hours worked per week) in their second year students with intensity decreasing in the final year (but still higher than the first year) Who works and why? Factors affecting the likelihood of working during term time include o Degree subject - with a lower proportion of students in sciences and life sciences working o Parental income – students with parents earning £35,000 or more are less likely to work o Financial support - incidence of work is lower among those with family support or scholarship o Parents’ education - Students with graduate fathers are less likely to work o Term time accommodation - those living with other students were less likely to work As indicated by their reasons for working students work more for consumption (to buy luxuries/pay for social life) reasons (68%), out of financial necessity (48%) or for debt reduction (43%), than to gain work experience (27% to gain general work experience, 16% career related) The most common reason given for not working was “it could impact on academic studies” (67%), with other reasons including “not needing to” (44%) and “it would affect social life” (31%) Self-reported effects of term-time employment (reported by survey respondents) Common reported negative effects of term time employment include “less time for study” (67%), “less time for social and leisure time” (54%) and “less sleep”(45%) Common reported positive effects include “general work experience” (62%), “increased confidence“(62%), “gained transferable skills” (61%) and “improved time management skills” (40%) On the whole more students had mixed views about whether working in term-time had an overall positive (35%) negative (33%) or no effect (32%) on their academic studies Actual effects of term-time employment (looking at final degree classification and taking into account all other factors affecting degree performance as mentioned above) On average term-time employment has no significant effect on degree performance but has a negative impact (particularly in terms of the likelihood of getting a first) for those who work out of financial necessity (who are disproportionately from lower socio-economic backgrounds) and those who work with a high intensity (with those working out of financial necessity also more likely to work with a greater intensity) 3 3. Labour market outcomes Early graduate destinations Destinations six months after graduation can be divided into three main groups – inactivity (either unemployed or other activity such as travelling), further study or employment Personal characteristics, socio-economic background, degree performance and degree subject have little impact on the likelihood of being inactive in the labour market – therefore inactivity is more likely to be influenced by differences in attitude or circumstances that we did not observe Of those who were active, factors affecting the likelihood of going into further study rather than employment include o Degree performance – first class achiever more likely o Degree subject – law and science students are more likely to go onto further study Type and quality of employment The majority of students enter either the banking, finance and insurance (38%) or the public administration, education and health (27%) sectors There are clear gender differences in industry and occupation. Almost half of men are in banking, finance and insurance compared with only 30% of women. Women (37%) are most likely to be in the public administration, education and health sector 60% of employed students gain a graduate level job within six months of graduation The factors affecting the likelihood of being in a graduate level job within six months of graduating include o Gender - Even after controlling for industry and region of employment, women are less likely to be in a graduate level job compared with men, and this holds across all subjects o School background - attending a independent school increases the odds of a graduate job o Degree classification - First class degree achievers are over twice as likely to be in a graduate job than upper second holders, with third class graduates less likely o Degree subject - graduates from engineering and construction management, vocational subjects (such as education, health and social care) and business subjects are the most likely to be in a graduate job o Degree/unpaid work experience - having done work experience as part of the degree or unpaid work experience increases the likelihood of being in a graduate job o Career motivation - Students with higher career importance relative to other life roles were more likely to have a graduate job Graduate starting salaries Earnings are higher in both the banking, finance and insurance, and the agriculture, energy, manufacturing and construction sectors, with earnings lowest in the distribution, hotels and restaurant sector 4 There are regional differences in salary with those from London followed by the South East having the highest earnings After controlling for industry and region of employment there are salary variations across different subjects, with higher earnings for graduates of engineering and construction management, business, vocational subjects and mathematics and IT Older students earn more – but this effect decreases with age, which is a commonly recognised phenomenon Holders of first class degrees earn significantly more compared to other degree classifications - on average they earn 8% more than upper second achievers Being employed for work experience reasons during term time has a positive effect on starting salary – but there is no effect of work experience undertaken during vacation periods Gender wage gap Men on average earn 12% more than women This gap can only be partly explained by differences in industry, region of employment, degree subject and personal characteristics. A large proportion of this gap is not explained by these factors, suggesting other sources of difference such as self-selection, attitude differences or discrimination Age has an impact on wages for women. Older women earn more than younger women but there is no impact of age for men Male graduates of sciences and vocational subjects receive a higher wage than female graduates in these subjects Men receive higher rewards from entering the banking, finance and insurance sector than women who enter these industries The gender gap is partly driven by the fact males are more likely to obtain jobs at the higher end of the pay scale 4. Main Implications of Results The findings suggest a number of potential policy implications. The research has shown that particular groups have different degree outcomes: mature students, those with non-traditional qualifications and overseas students have a greater variation in performance, indicating a greater diversity of students in these groups. Therefore universities need to understand the greater variation in needs within these groups of students, especially as we identified the affect of the various determinants of degree performance varied between “traditional” (young British students with A-levels) and “non-traditional” students. Results from the employment survey indicated there are a group of students (25% of all respondents) who work during term time out of financial necessity and these are the students for whom term time employment has a negative impact on degree performance. Financially constrained students may have less control over the level of employment they undertake which may partly cause the detrimental effects on their performance. This has serious implications for the funding of students that are forced to work, with greater financial help needed for such students, although the new system of student grants introduced in the 2006/2007 academic year for the poorer students may help alleviate this situation. However, 5 the National Union of Students (NUS) has recently raised concerns about this new funding system There is also evidence that working for experience reasons during term time (but not during vacations) has a positive effect on wages after graduation. This indicates that employers are attracted to students who have worked for experience reasons during term time, possibly because they have been able to juggle their studies along with relevant work experience, which shows a high level of motivation and organisational skills. Universities should try to help/encourage those students who have to work for financial reasons to find suitable (i.e. experience-bearing) employment, since this may lead to greater labour market success. Our findings also suggest that graduate employers need to be aware that some students are forced to work, which may impact on their degree performance, e.g. students with an upper second that worked, may be of the same ability as an individual with a first that did not work. There are clear subject differences across both degree and labour market outcomes, which suggests that students could benefit from strategic selection of subjects in which they are more likely to get a good degree and that have the highest rewards in the labour market. These findings support the need for change in the degree classification system, as recommended by the recent Burgess report1, since it is becoming increasing difficult for employers to distinguish among the growing number of upper second achievers so employers are drawn to particular subjects. The research also found that achievement prior to university (as measured by UCAS points) was a strong predictor of degree performance, with the strength of this relationship varying across subjects. It could be argued that, in relative terms, higher education does not really add anything, since the people who come out with the top degrees are those who entered with the higher entry qualifications. High ability students cannot afford not to go to university, since this is the only way to signal their ability. It is therefore important to gain value through other means beyond academic achievement such as through work experience in order to distinguish oneself amongst an expanding pool of graduates. Some of our findings about gender are in contrast to earlier results in the literature. Previous research found that men were more likely to get firsts. Our research suggests that, at least at the University of Reading, the gender gap in higher education achievement has closed with women now either equally or more likely (especially in the case of some male dominated subjects) to get a first than men in all subjects. There are gender differences in the way factors influence degree performance. Age has a much stronger positive effect for men, suggesting that factors, such as immaturity and motivation, may be hindering young males’ performance. We in fact observed that women had higher career importance scores which could act as a proxy for motivation. More research is needed to investigate differences in subject choice by gender, since we found that women were more likely to get a first than men in subjects that were male dominated. This highlights that subject choice may be connected to unobserved predictors of degree performance such as motivation, ambition and natural aptitude. If certain subjects attract students with such qualities, this may also mean subject has a signalling effect in the labour market if employers believe that students with desirable attributes are attracted to certain disciplines. 1 Burgess, R. (2007) Beyond the honours degree classification: Burgess Group Final Report. Universities UK. 6 However, despite achieving better degree performance women are faring less well than men on entry to the labour market. Our results indicate their labour market outcomes are partly connected to subject of degree, industry and occupation choice, but even after controlling for these there is still a gender gap, particularly with salary. This gender gap is partly driven by men, on average, obtaining more prestigious jobs and being at the top end of the pay scale. It is difficult to draw out the reasons for the gender differences, but age had an effect on wages for females but not for men. This age effect may indicate that younger women are less confident or perform less well in interviews than older women, whilst men have the same level of confidence across the age distribution. We identified that women have lower career decision-making self-efficacy (CDMSE) scores than men. Therefore further research needs to examine if it is women’s attitudes, expectations or preferences (leading them to select certain occupation and wage levels) or actual discrimination that explain these labour market differences. If there are gender differences across attitudes to careers this has implications for the delivery of career education. Previous studies have shown that most graduates do eventually obtain graduate level employment within 3-4 years of graduating, but that those who gain graduate employment more quickly do better in the long-term. Our findings indicate various factors that influence the speed at which graduates are able to obtain graduate employment. For example females, those not from independent schools and graduates from certain non-vocational subjects within the arts, humanities and social sciences are less likely to gain graduate employment within 6 months of graduation. These results are suggestive of continued social stratification arising from schooling, and highlight the importance of choice of degree subject for later outcomes. Publications and Future Research Expected salary – In collaboration with John Jerrim at the University of Southampton – using data obtained from the 2006 and 2007 Reading undergraduates surveys, used in the thesis, this project aims to look at how realistic students’ expected salary upon graduation is, how this varies across the course of a degree and the effect of the CMS module on salary expectations National HESA/DLHE data – In collaboration with Dr Alessandra Faggian at the University of Southampton – apply ideas from the thesis to national HESA/DLHE Comparative study of student employment in other universities – Other universities are interested in using our survey to conduct their own study of student employment – which would enable a joint comparative study of student employment across universities For further information please contact Dr Zella King on z.m.e.king@reading.ac.uk or Sarah Jewell on s.l.jewell@reading.ac.uk 7