Northern Rivers Regional Biodiversity Management Plan

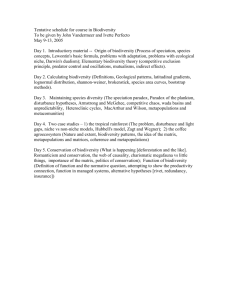

advertisement