The warm waters of coral reefs are rich in marine life

advertisement

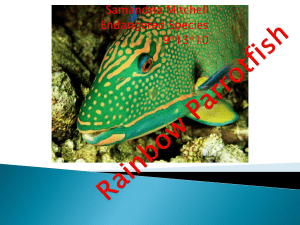

The warm waters of coral reefs are rich in marine life. Odd shapes, bright colors and distinctive color patterns enhance the appearance as well as the survival of many of the animals that live there. Parrotfish are among the most colorful fish found on reefs. Their unusual mouth is formed by large teeth that are fused together. The teeth's resemblance to the beak of tropical birds earned this group the nickname "parrotfish." These reef fish graze on algae that cover the surfaces of rocks and dot the re ef bottom. While a parrot's strong beak is used to crack open nuts and seeds of rainforest plants, parrotfish use their teeth to bite off pieces of stony coral. This may seem like an unappetizing meal, but some parrotfish seem to prefer it. It is not the hard coral skeleton that provides nourishment, but the soft bodied structures coral polyps that grow on the surface of the skeleton. The polyps look like miniature sea anemones, except that most live connected together in colonies contain ing hundreds of individuals. Living in coral polyp cells are single-celled algae known as zooxanthellae. Zooxanthellae are the reason why parrotfish eat coral! Any coral skeletal material that is swallowed is crushed by the grinding action of special teet h found in the parrotfish's throat called the pharyngeal mill.This makes its way through the fish's digestive system and is deposited on the reef as white coral sand. Some fish return to the same spot to release their waste products which form small hills of sand. It has been estimated that parrotfish produce as much as one ton of coral sand per acre of reef each year. Classification and Characteristics Early scientists identified over 350 different kinds of parrotfish, but it is now known that there are only 80 members of Family Scaridae. The early confusion came about because these fish have a number of color phases which look quite different. There is still some disagreement, but among Atlantic species most people recognize two major genera, Scarus and Sparisoma. Sparisoma is restricted to the Caribbean, while Scarus is found in all tropical seas and even the Mediterranean Sea. Two smaller genera, Cryptotomus and Nicholsina are also found in the Caribbean. Close relatives of parrotfishes are the wrasses. Wrasses also have "buckteeth" but they are not fused together like parrotfishes'. However, wrasses are not plant eaters and feed on zooplankton an d larger invertebrates. Aside from eating coral polyps and perhaps an occasional mollusk, parrotfish are algae eaters. The different types of parrotfish can be told apart by the way in which their upper and lower teeth meet. Scarus have teeth that most closely resemble a parrot's beak. The upper teeth stick out and cover up the lower. They are also large fish , sometim es reaching four feet, bright and colorful and known to swim in schools. Some male Scarus develop a hump on their foreheads, which is especially noticeable in the blue humphead parrotfish. In Sparisoma, however, the upper teeth fit inside of the lower tee th. They are usually small fish, under one foot in length. They are less colorful, mostly reds, browns and grays and swim alone or in small groups. Cryptotomus and Nicholsina, which have a more cigar shape like the wrasses, do not have teeth that overlap at all. Instead, their teeth are more distinct, and not completely fused into a beak. In general, parrotfish have large, thick scales, strong enough to stop a heavy spear in some species. The scales have been used to decorate basketwork and shellflower arrangements. Many Caribbean and Indo-Pacific parrotfish are eaten. In Hawaii, they a re called ohu, palukaluka and lauia and eaten raw. At one time, Hawaiians considered the parrotfish so special that only royalty could touch them. Adaptations and Reproduction At night, parrotfish do not graze, but sleep on the reef bottom. Some bury in the sand like wrasses. Others, certain species of Scarus, have developed the unique ability to enclose themselves in a see-through covering at night called a mucus cocoon. Th e cocoon is secreted in just thirty minutes and provides excellent protection from night predators such as moray eels. It seems to prevent other animals from picking up the scent of parrotfish. In addition to being produced at night, it is thought that a mucus cocoon is also made if there is not enough oxygen in the water. Parrotfish have a number of other interesting features, some of which are shared by the wrasses. Both of these families of fish use the same method of swimming in which the pectoral fins, found just behind the gills, are used in a manner similar to row ing. These fins make quick up-and-down movements to propel wrasses and parrotfish forward, whereas most other fish rely on their caudal or tails fins. However, parrotfish do use their bluntly shaped tails when they need a quick burst of speed. In 1968 is was found that parrotfish, like wrasses, can undergo sex reversal. In this case, a female fish becomes a male. Therefore, parrotfish can be born male and remain male throughout their lives (primary males) or they can be born female and chang e sex and color to become a male (secondary males). Secondary males are sometimes called supermales or terminal males. Females and primary males look alike and are red, gray, brown and black. Secondary males are bright green, blue, red and yellow. There a re also some species that maintain the same colors throughout their lifetime. As if this is not confusing enough, some parrotfish can change their colors to match the surroundings. Various color phases are also seen in wrasses, some are associated with sex change and others are not. Among blueheaded wrasses, primary males and females are yellow, sometimes with a black stripe. When he reaches a certain size, the primary male may c hange colors and become a supermale. The supermale has a blue head, black stripe and greenish-blue body. Supermales maintain a harem of females with which they mate. They also establish a site just for spawning and other males are not allowed to enter thi s territory. If the colorful supermale is removed from the harem, the most aggressive female, usually the largest, immediately begins to dominate the harem. Within two to four days, this female has changed color and sex to become a blueheaded supermale. T he new male can now fertilize the eggs of the harem members. In some species of wrasses, it is simply the largest female who changes sex. Although they are not known to have harems, it is possible that dominance and size plays a part in sex reversal among the parrotfishes as well. Parrotfish spawn or produce eggs all year round, although this activity is more frequent in the summer. Some species move to specific areas to spawn, typically into deeper areas of the reef. Supermales pair up with one female to spawn, while primary ma les mate with small groups containing one female and several males. After spawning, they return to the shallow water at night. Fertilized eggs hatch after 25 hours. The larvae are only 1.7 mm long and have no eyes, mouth or pigment. A mouth does not appear until the third day after hatching. It is not known how long the larval stage lasts in these anim als.