Association of Molecular Pathology v US Patent and

advertisement

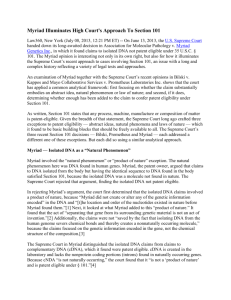

Text Box: Litigation over BRCA patents in the United States and Australia Association of Molecular Pathology v US Patent and Trademark Office (the “Myriad” or “BRCA” case) Over twenty plaintiffs sued the US Patent and Trademark Office, Myriad Genetics, and Trustees of the University of Utah Research Foundation on May 9, 2009 in the US Federal District Court located in New York City.1 The plaintiffs were identified by, and their main legal representation has been provided by the American Civil Liberties Union and the Public Patent Foundation. The suit challenged 15 claims in 7 patents exclusively licensed to or assigned to Myriad Genetics, Inc. On March 29, 2010, Judge Robert Sweet ruled that all 15 claims were invalid, with two separate sections of his decision—one focusing on claims to isolated DNA molecules (“composition of matter” claims) and the other section about method claims. Myriad appealed the decision to the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit, an appeals court established in 1982 that hears patent cases and certain other matters of federal law. On July 29, 2011, a three-judge panel handed down its first ruling.2 Three parts of the ruling were unanimous. All three judges affirmed Judge Sweet’s invalidation of five method claims. All three reversed his invalidation of one method claim on a cancer drug assay (that is, they upheld the claim). All three judges also affirmed that modified DNA molecules that have been engineered and do not correspond to sequences found in nature are patent-eligible. This includes vectors, complementary DNA and other claims commonly found in “gene patents,” which are affirmed as patent-eligible. On the question of whether isolated DNA molecules corresponding to sequences that would be found in nature, however, the judges differed. All three judges wrote at length, with most of the analysis focused on this point of disagreement. Judge Lourie wrote the majority opinion and concluded that the isolated DNA molecules claimed in Myriad’s patents are chemically different and thus patent-eligible since they are not found in nature. DNA’s covalent bonds have been broken, and so the isolated DNA molecules are chemically distinct and patent-eligible. Judge Moore agreed on patent-eligibility of isolated DNA, but gave different reasons, using a test of distinctive utility associated with isolated fragments in addition to chemical differences. Hers is a structure plus function criterion. She also indicated her decision might have been different if many investors and inventors had not developed settled expectations about what is patented. Those expectations would be disrupted by declaring genes and gene fragments ineligible for patents. Judge Bryson dissented, concluding that DNA molecules with sequences found in nature are not patent-eligible. His dissenting opinion is similar to arguments in an amicus curiae brief that was submitted to the court by the US Government and defended by the US Solicitor General in an unprecedented personal appearance before the CAFC. The upshot of this ruling was that five method claims were invalidated, one was upheld, the patent-eligibility of engineered DNA was re-affirmed, but the patenteligibility of DNA molecules corresponding to those found in nature was the subject of disagreement—the majority saying “patent eligible” and Judge Bryson arguing in dissent that it is not, basically agreeing with the Solicitor General’s view. The case was appealed to the US Supreme Court, which remanded the case back to the CAFC (in effect, requiring the CAFC to review its previous ruling), in light of a March Supreme Court decision in Mayo v Prometheus. In Mayo, all nine Supreme Court justices ruled that a method patent on dosing of thiopurine drugs based on measuring a metabolite is not patentable subject matter. Mayo is about method claims, whereas the only claims still under dispute in the Myriad patents are on isolated DNA molecules. The line of reasoning used in Mayo was that laws of nature, products of nature, and abstract concepts are not patentable subject matter. The Supreme Court left little doubt that it intended the threshold “patentable subject matter” criterion to do work in addition to criteria such as novelty, utility, nonobviousness (or “inventive step”), enablement and written description (full disclosure) derived from other provisions of the patent statute. On August 16, 2012, the CAFC once again issued a ruling, reaching the same conclusions as in 2011.4 Judges Lourie and Moore reiterated their arguments and Judge Bryson again dissented. The Solicitor General once again argued that DNA molecules corresponding to sequences found in nature should not be patent-eligible in a second amicus curiae brief. Judges Lourie and Moore argued that the Supreme Court’s decision in Mayo is not directly applicable to the claims on isolated DNA molecules because Mayo addresses method claims, not composition of matter claims. Judge Bryson’s dissent and the Solicitor General’s amicus brief argue that Mayo is relevant by analogy, and the underlying problem is the same—that exclusive rights extend too far upstream and pre-empt research and follow-on invention beyond the contributions of the inventors. In September 2012, ACLU once again petitioned for Supreme Court review. The Court should decide in late 2012 whether to review the case. Cancer Voices Australia v Myriad Several patents in Australia pertain to BRCA1/2 testing. Rights to those patents in Australia and New Zealand were licensed by Myriad to Genetic Technologies Ltd (GTG), an Australian firm that holds patent rights to use of intronic DNA sequences. The licensing agreement resulted from a cross-licensing agreement. A patent dispute between the two firms over their respective patent holdings led to the settlement, as described by Gold and Carbone.3 GTG then announced it would not enforce its BRCA patent rights against Australian provincial health department laboratories, but instead announced BRCA rights would be the firm’s “gift” to the people of Australia. When GTG was under financial pressure in the summer of 2008, however, the CEO announced an intention to start enforcing patent rights, which triggered a media firestorm. By October, the company, now under new management, announced it would not enforce its BRCA patent rights. Partly in reaction to the public controversy, the Australian Senate held a series of hearings, and prepared a report.5 Cancer Voices Australia also sued Myriad and GTG in a case that went to trial in February 2012.6 That trial is over, and the court’s decision is pending. 1. Association of Molecular Pathologists v US Patent and Trademark Office. US District Court, Southern District of New York, 2009-cv-04515-RWS, March 16, 2010. 2. U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit. Association of Molecular Pathology v US Patent and Trademark Office, US Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit, 2010-1406, July 29, 2011. 3. Gold ER, Carbone J. Myriad Genetics: In the eye of the policy storm. Genet Med 2010;12(4 Suppl):S39-70. 4. Association of Molecular Pathologists v US Patent and Trademark Office. Rev'd in part; aff'd in part ed: US Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit, 2010-1406, August 16, 2012. 5. Legal and Constitution Affairs Legislation Committee, Australian Senate, "Patent Amendment (Human Genes and Biological Materials) Bill 2010, September 2010 (ISBN: 978-1-74229-475-9). 6. Cancer Voices Australia et al. v. Myriad Genetics Inc. et al. Federal Court of Australia, NSD643/2010, 8 June 2010.