Quantification of airborne bacteria and fungi using solid phase

advertisement

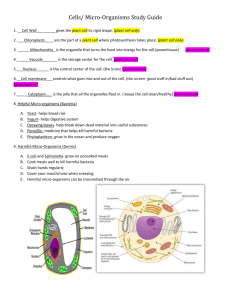

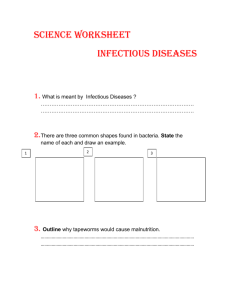

1 Enumeration of airborne bacteria and fungi using solid phase cytometry Lies M. E. Vanhee, Hans J. Nelis, Tom Coenye* Laboratory for Pharmaceutical Microbiology, Ghent University, Harelbekestraat 72, B-9000, Ghent, Belgium *Corresponding author: Tom Coenye Laboratory for Pharmaceutical Microbiology Ghent University Tel.: +32 9 2648141 Fax: +32 9 2648195 Email: Tom.Coenye@UGent.be 2 1 Abstract 2 Conventional methods for the enumeration of airborne micro-organisms are 3 inaccurate and time-consuming, hence the interest in novel approaches is increasing. 4 In the present study, the use of solid phase cytometry (SPC) was evaluated for the 5 enumeration of airborne micro-organisms. A 4 h SPC procedure based on viability 6 staining was applied to samples from 50 locations and compared with an optimised 7 culture-based method. Plate counts after air sampling were repeatable but strongly 8 dependent on sampling volume. Samples with low or high microbial load were 9 difficult to analyse using the culture-based method, unlike with SPC. Results show 10 that SPC can be considered superior to the culture-based method because of its much 11 higher dynamic range, its speed and its ability to enumerate not only culturable but all 12 viable micro-organisms. 13 14 15 Keywords: Solid phase cytometry (SPC); Bioaerosol; Airborne micro-organisms 3 16 1. Introduction 17 In recent years, monitoring of the number of airborne micro-organisms has 18 gained interest due to increasing concerns about public health, the threat of 19 bioterrorism, surface biodeterioration and spread of plant diseases (Douwes et al., 20 2003; Pieckova and Jesenska, 1999; Stetzenbach et al., 2004). Exposure to 21 bioaerosols, containing airborne micro-organisms and their by-products, can result in 22 respiratory disorders and other adverse health effects such as infections, 23 hypersensitivity pneumonitis and toxic reactions (Fracchia et al., 2006; Gorny et al., 24 2002). In many environments including hospitals, animal sheds, clean-rooms, 25 pharmaceutical facilities and spacecraft environments, the presence of bioaerosols can 26 compromise normal activities, making efficient monitoring crucial (Gorny, 2004; 27 Stetzenbach, 2007; Venkateswaran et al., 2003). 28 Conventional enumeration of airborne micro-organisms relies on culture- 29 based or microscopic methods. Although culture-based analysis is most widely used 30 for bioaerosol quantification, it often results in an underestimation of the number of 31 micro-organisms. First of all, only culturable micro-organisms are detected, while the 32 non-culturable ones, which can comprise a significant percentage of the bioaerosol, 33 are overlooked (Angenent et al., 2005; Chen and Li, 2005; Dillon et al., 1999; Wu, 34 2007). Secondly, because of differences in growth requirements, no single culture 35 condition will allow detection of every type of micro-organism (Green et al., 2005; 36 Venkateswaran et al., 2003). Finally, because of the need of microbial multiplication, 37 analysis usually takes at least three days to complete and fast-growing micro- 38 organisms may overgrow slow growers (Niemeier et al., 2006; Wu, 2007). 39 In contrast, microscopic methods allow the detection of both culturable and 40 non-culturable micro-organisms and results can be obtained within hours of sample 4 41 collection (Angenent et al., 2005). However, microscopic enumeration is laborious, 42 requires a high level of expertise and results are often highly variable (Cruz and 43 Buttner, 2007). The inaccuracy and the time-consuming nature of conventional 44 methods underscore the need for new, rapid techniques that generate reliable data. 45 Recently flow cytometry, immunofluorescence, PCR and different biochemical assays 46 targeting e.g. ß,1-3-D-glucan, ergosterol and ATP, were suggested as alternative 47 strategies for the quantification of airborne bacteria and fungi (Alvarez et al., 1995; 48 Giovannangelo et al., 2007; Lange et al., 1997; Prigione et al., 2004; Robine et al., 49 2005; Venkateswaran et al., 2003). 50 In solid phase cytometry (SPC), the principles of epifluorescence microscopy 51 and flow cytometry (Lisle et al., 2004) are combined. Micro-organisms are retained 52 on a membrane filter, fluorescently labelled and automatically counted by the 53 Chemscan RDI laser-scanning device. Each detected spot can visually be inspected 54 using an epifluorescence microscope (De Vos and Nelis, 2003; Mignon-Godefroy et 55 al., 56 carboxyfluorescein diacetate (ChemChrome V6) by esterases, resulting in the 57 formation of fluorescent carboxyfluorescein in intact and metabolically active cells 58 only (Joux and Lebaron, 2000). SPC is considerably faster than conventional 59 enumeration methods, does not depend on culture and has a theoretical detection limit 60 of only one cell per filter and, hence per filtered volume (Van Poucke and Nelis, 61 2000; Vermis et al., 2002). Additionally, SPC can successfully be used to determine 62 the microbial load of highly contaminated samples, since it has a high dynamic range 63 with an upper limit of approximately 10, 000 cells per membrane filter (De Vos and 64 Nelis, 2006; Reynolds and Fricker, 1999). 1997). Fluorescent viability staining is based on the cleavage of 5 65 In the present study, the total number of bacteria and fungi in air samples is 66 determined by SPC and compared with results obtained by a conventional culture- 67 based method. To this end, airborne micro-organisms from a large number of diverse 68 locations were impacted on culture media and on a water soluble bio-polymer and 69 analysed by SPC. 70 71 2. Materials and methods 72 2.1. Air sampling device 73 For the collection of airborne micro-organisms, the MAS-100 Eco impaction 74 air-sampler (Merck) with an airflow of 100 l min-1 was used. All culture results were 75 converted using a positive hole conversion table according to the manufacturers 76 instructions and expressed as colony forming units (CFU) m-3. 77 78 2.2. Culture-based method 79 2.2.1. Repeatability of air sampling 80 To examine the variation in bioaerosol sampling, 100 l of air was impacted 81 successively onto 10 culture plates. For this analysis, tryptic soy agar (TSA, Oxoid), 82 TSA supplemented with 0.2% cycloheximide (Sigma) (TSAc) and rose bengal 83 chloramphenicol (0.1 g l-1) agar (RBCA, Sigma) were used. Subsequently, plates were 84 incubated at 20°C and colonies were counted after 3 days. 85 86 2.2.2. Optimisation of the culture-based method 87 Different media were tested for the growth of airborne micro-organisms: TSA, 88 TSAc, RBCA, Sabouraud agar (Oxoid) supplemented with 0.1% chloramphenicol 89 (Sigma) (SABc), R2A agar (containing yeast extract [0.5 g/l], proteose pepton n°3 6 90 [0.5 g/l], casamino acids [0.5 g/l], dextrose [0.5 g/l], soluble starch [0.5 g/l], sodium 91 pyruvate [0.3 g/l], potassium phosphate dibasic [0.3 g/l], magnesium sulfate [0.05 g/l] 92 and agar [15 g/l]) and different dilutions (1:2, 1:10, 1:100) of TSA and TSAc. For 93 these experiments, air samples (100 l) were collected at several locations, plates were 94 incubated at 30°C and colonies were counted after 3 days. To determine the influence 95 of the sampling volume, samples of 10, 50, 100 and 1000 l were collected on TSA 96 and colonies were counted after 4 days of incubation at 20°C. For the comparison of 97 different incubation conditions, samples (100 l) were collected on TSA, TSAc and 98 RBCA. The plates were incubated at 20°C or 30°C and colonies were counted after 2, 99 3, 4 and 7 days. 100 101 2.2.3. Air sampling and culturing 102 Air samples were collected using the MAS-100 Eco at 50 locations, expected 103 to range from a very low bioaerosol concentration in clean-rooms to a high 104 concentration in agricultural settings. According to the expected concentration of 105 airborne micro-organisms, a sampling volume of 10 or 100 l was chosen (Table 1). At 106 each location, samples were collected in triplicate on petri dishes containing 25 ml of 107 agar medium. Culture conditions were based on results obtained during optimisation 108 of the method and are described below. 109 110 2.3. Solid phase cytometry 111 2.3.1. Collection of air samples 112 For analysis with SPC, air samples were collected at each location on three 113 ready-to-use Polym’Air plates (Chemunex), containing a synthetic, nutrient-free, 114 water soluble polymer. 7 115 116 2.3.2. Preparation of samples 117 Immediately after sampling, the polymer was aseptically removed from the 118 petri dish and subsequently dissolved in 20 ml of physiological saline, which had 119 previously been filtered (0.22 µm pore size membrane filter, Whatman Schleicher & 120 Schuell) to eliminate particles. For each sample the total viable count (TVC) and the 121 fungal count were determined. 122 123 2.3.3. Total viable count labelling protocol 124 Depending on the estimated bioaerosol concentration, different volumes 125 (Table 1) of the dissolved Polym’Air samples were filtered over a 0.4 µm Cycloblack- 126 coated 127 counterstained by filtration of one ml CSE/2 (Catala et al., 1999), the filter was 128 transferred to a cellulose pad soaked with 600 µl of the activation medium ChemSol 129 A4 and incubated at 37°C for 3h. Finally, the filters were incubated at 30°C for 30 130 min on a cellulose pad saturated with 600 µl of staining reagent (ChemChrome V6 131 diluted 1:100 in the labelling buffer ChemSol B16). All reagents were obtained from 132 Chemunex and filtered before use. polyester membrane filter (Chemunex). Interfering particles were 133 134 2.3.4. Fungal count labelling protocol 135 Samples were filtered over a 2.0 µm Cycloblack-coated polyester membrane 136 filter and filters were incubated at 30°C for 3h on 600 µl of the activation medium 137 Chemsol A6. Subsequently, viable micro-organisms were fluorescently labelled by 138 incubating the filters at 37°C for 1h on a cellulose pad saturated with 600 µl of fungal 139 staining reagent (ChemChrome V6 diluted 1:100 in the labelling buffer ChemSol B2). 8 140 141 2.3.5. Laser scanning 142 After labelling of the micro-organisms, the 25 mm diameter membrane filter 143 was placed in a holder, on top of a support pad (Chemunex) moistened with 600 µl of 144 labelling buffer. The filters were subsequently scanned by the Chemscan RDI. This 145 solid phase cytometer consists of a argon laser, emitting light of 488 nm and two 146 photomultiplier tubes, which detect the fluorescent light emitted by the labelled cells. 147 The produced signals are processed by a PC, applying a series of software 148 discriminants to differentiate valid signals (labelled bacteria/fungi) from fluorescent 149 particles. Different software settings were used for the two protocols as bacteria and 150 fungi or only fungi had to be retained, respectively. Results were displayed as green 151 spots on a membrane filter image in a primary and, after software elimination of 152 background, secondary scan map. 153 154 2.3.6. Microscopic validation 155 To confirm and further analyse the properties of the detected spots, visual 156 inspection using an epifluorescence microscope (Olympus BX40) equipped with a 157 computer-driven moving stage, was performed. In practice, the filter holder was 158 placed on the moving stage so as to retain the holder and the membrane filter in 159 exactly the same position as in the Chemscan RDI. Subsequent highlighting of a green 160 spot in the secondary scan map resulted in the direction of the microscope to the 161 respective position on the membrane filter. For the TVC-protocol, the fluorescent 162 spots were validated based on fluorescense intensity, line amplitudes and shape, 163 discriminating between bacteria, fungi and particles. For the fungi-protocol, the 164 validation consisted only of the differentiation between fungi and fluorescent 9 165 particles. Results were expressed as the mean corresponding number of bacteria or 166 fungi per m3. 167 168 2.3.7. Storage of the dissolved samples 169 In order to investigate if storage in the dissolved Polym’Air has an influence 170 on the viability of the collected micro-organisms, analysis was performed 171 immediately and 4 h and 24 h after dissolution of the Polym’Air. To that end, airborne 172 micro-organisms were collected onto six Polym’Air plates which were immediately 173 dissolved into 20 ml of physiological saline. Each sample was analysed with the 174 modified TVC-protocol at t = 0 and subsequently stored at 4°C and re-analysed after 175 4 h or 24 h. 176 177 2.4. Statistical analysis 178 Ratios between the cells detected using SPC and the corresponding colony 179 counts were calculated and Mann-Whitney and Kolmogorov-Smirnov tests were used 180 to determine if there was a statistically significant difference between the results 181 obtained with the culture-based method and SPC (SPSS 15.0.0, SPSS Inc.). The 182 criterion for significance for all analyses was p < 0.05. 183 184 3. Results and discussion 185 3.1. Culture-based method 186 3.1.1. Optimisation of the culture-based method 187 Results demonstrated that upon successive air sampling plate counts are 188 repeatable (data not shown). In order to optimise the culture-based method before 189 comparison with SPC, different media, sampling volumes and incubation conditions 10 190 were examined. To check the specificity of the different media, the recovered micro- 191 organisms were Gram-stained. As expected, TSAc and RBCA were specific for 192 bacteria and fungi, respectively. SABc allowed the growth of both bacteria and fungi, 193 and was therefore excluded from further experiments. Sampling on R2A agar and 194 TSA resulted in similar counts (data not shown), but as incubation periods were 195 longer for R2A agar, we prefered the use of TSA as a general growth medium. 196 Dilution of TSA led to lower counts than undiluted TSA (data not shown). It was also 197 noted that, as the sampling volume increased, the number of CFU m-3 decreased (Fig. 198 1). This phenomenon was previously described by Nesa et al. (2001) and can be 199 explained by desiccation of the micro-organisms and dehydration of the agar medium 200 when longer sampling times (required to sample larger volumes) are used. Sampling 201 volumes should therefore be as low and sampling times as short as possible. However, 202 extremely low colony counts obtained after sampling small volumes may lead to 203 considerable error in the estimation of the microbial load. Finally, different incubation 204 conditions were examined and results show that incubation at 20°C for four days 205 yields optimal recovery of both fungi and bacteria (data not shown). In summary, 206 TSA, TSAc and RBCA are proposed for growing all micro-organisms, bacteria and 207 fungi, respectively and incubation is performed at 20°C for a minimum of four days. 208 The sampling volume might need adjustment after initial determination of the 209 bioaerosol concentration and should be kept to a minimum sufficient to obtain 210 representative counts. 211 212 3.1.2. Air sampling and culturing 213 The optimised cultured-based method was subsequently used to enumerate 214 micro-organisms in air samples collected at 50 diverse locations (Table 1). The 11 215 culturable microbial population in the samples ranged from 7 to 5.9 x 106 CFU m-3 216 with bacterial counts ranging from 9 to 6.0 x 106 CFU m-3 and fungal counts ranging 217 from 0 to 6033 CFU m-3. For most locations, plates were countable when 100 l of air 218 was sampled. However, when locations with extremely high (e.g. pig and chicken 219 stables) or low (e.g. clean-rooms) microbial loads were sampled, reliable estimation 220 of the number of micro-organisms present became impossible (Table 1). 221 222 3.2. Solid phase cytometry 223 Table 2 presents results on the viability of micro-organisms after storage in 224 solutions of Polym’Air. After 4h storage the number of cells detected is similar to the 225 one obtained after immediate analysis (Mann-Whitney test). Since the SPC procedure 226 takes 4 h, this indicates that samples can be re-analysed, using a lower volume, when 227 counts initially fall outside the dynamic range of the Chemscan RDI. However, 228 storage of micro-organisms in the Polym’Air solution for 24 h led to a marked decline 229 in the number of viable cells (Table 2). 230 Validation was easy to perform using both SPC protocols, since 231 counterstaining with Chemsol CSE/2 and use of a membrane with a 2.0 µm pore size 232 for the TVC and the fungi protocol respectively, were sufficient to eliminate most 233 interfering particles. Less than ten particles, which could easily be recognized by their 234 shape, were present in all secondary scan maps. 235 Table 1 gives an overview of the SPC results obtained for all samplings. Total 236 counts ranged from 141 to 9.4 x 105 CFU m-3, with bacterial counts ranging from 89 237 to 9.3 x 105 CFU m-3 and fungal counts ranging from 30 to 1.2 x 104 CFU m-3. Fungal 238 counts obtained with the TVC-protocol and the fungi-protocol were comparable (data 239 not shown). Consequently, the use of the fungi protocol can be avoided and counts for 12 240 both bacteria and fungi can be obtained using one protocol, making analysis less 241 complicated and expensive. Accurate analysis of air samples containing low numbers 242 of micro-organisms was possible with SPC. Analysis of samples with high microbial 243 load, however, led to aborted scans due to an excessive number of fluorescent spots 244 (Table 1). These samples can be re-analysed by filtering a lower volume of the stored 245 sample. 246 247 3.3. Comparison between the culture-based method and solid phase cytometry 248 When comparing the culture-based method and SPC, SPC is a technically 249 more demanding technique for the enumeration of airborne micro-organisms. 250 However, an important advantage of SPC is that results are obtained very rapidly 251 (within 4 to 8h) while culture-based analysis requires at least 4 days. 252 Results obtained for 50 locations using both the culture-based method and 253 SPC were compared by calculating the ratio between the number of cells determined 254 by SPC and the CFU obtained with the culture-based method, and by performing the 255 Mann-Whitney and Kolmogorov-Smirnov tests for TVC, bacterial and fungal counts 256 (Table 1). The ratios for TVC, bacteria, and fungi were higher than one for 81%, 85% 257 and 84% of the samples respectively (Fig. 2). This indicates that in general more 258 micro-organisms were detected with SPC than with the culture-based method. The 259 Mann-Whitney test revealed that there was a statistically significant difference 260 between the SPC counts and plate counts for 64%, 59% and 58% of the samples for 261 the TVC, bacterial and fungal counts, respectively. For only three samples (12, 13, 262 38), counts obtained with SPC and the culture-based method for TVC and bacteria 263 were significantly higher for the latter. For only two samples (10, 16) significantly 264 more fungi were detected with the culture-based method. These unexpected results are 13 265 most likely due to sudden changes in the microbial load between samplings by 266 environmental variation. 267 Although SPC requires more manipulation of the samples, standard errors are 268 comparable between both methods (Kolmogorov-Smirnov test), suggesting that 269 differences between samplings are only caused by variation in air sampling caused by 270 sudden changes in the environment. 271 Enumeration of airborne micro-organisms in samples with low microbial load 272 with the culture-based method was prone to error since only very low numbers of 273 colonies were obtained. However, SPC can be used to analyse these samples because 274 it has a much lower detection limit (one cel per membrane filter). Accurate analysis of 275 samples with high microbial load was impossible with the culture-based method 276 because the colonies present on the plates were too numerous to count. Using SPC, 277 however, it is possible to analyse these samples, although re-analysis of the 278 appropriate dilution may be necessary. 279 280 3.4. Comparison between other non-culture-based techniques and solid phase 281 cytometry 282 Limitations to conventional methods for the enumeration of airborne micro- 283 organisms have led to the development of techniques for bioaerosol monitoring with 284 increased sensitivity and accuracy. One of these techniques is flow cytometry (FC). 285 FC was used by Lange et al. (1997) and Prigione et al. (2004) to quantify the 286 microbial load in air samples. The results obtained in these studies clearly showed that 287 FC was more precise and reliable than epifluorescence microscopy but that it suffered 288 from a relatively high detection limit (103 cells/ml). In addition, high background 289 fluorescence was observed for several samples. In contrast, SPC has a theoretical 14 290 detection limit of one cell per filter and our results from clean-room environments 291 confirm that SPC can be used for the enumeration of airborne micro-organisms in 292 setting with low numbers of micro-organisms. In SPC, the implementation of a 293 counterstaining procedure (Catala et al., 1999) and visual validation by 294 epifluorescence microscopy allows to easily make the distinction between particles 295 and micro-organisms. 296 Several biochemical assays for the enumeration of airborne micro-organisms 297 are available, targeting biological compounds like ß,1-3-D-glucan, ergosterol or ATP 298 (Giovannangelo et al., 2007; Robine et al., 2005; Venkateswaran et al., 2003). 299 However, the applicability of some of these assays is limited (e.g. ß,1-3-D-glucan and 300 ergosterol can be used only for fungi) and it is often difficult or impossible to 301 correlate the results obtained with cell numbers. 302 Although PCR-based approaches are widely used to quantify micro-organisms 303 (for a review see Zhang and Fang, 2006), there is only a single study in which PCR is 304 used for bioaerosol monitoring (Alvarez et al.,1995). In this study, it was concluded 305 that the PCR procedure has a detection limit of 10 cells when an additional 306 reamplification and hybridization was performed, leading to a 9 h procedure. 307 Compared to this method, SPC is much faster. 308 309 4. Conclusions 310 To our knowledge, SPC has so far not been used to enumerate airborne 311 bacteria and fungi. Our data suggest that SPC is superior to culture-based methods 312 because of its much higher dynamic range, its speed and the ability to enumerate all 313 viable micro-organisms. The main advantage of SPC is the low detection limit 15 314 making it particularly suited for the analysis of air samples with low numbers of 315 micro-organisms. 316 317 Acknowledgements 318 We acknowledge the excellent technical assistance of Margherita Battista. We 319 also thank Nadine Carchon, Linda De Bock, Anneke Derore, Sarah De Smet, Kurt 320 Houf and Peter Van Daele for giving the opportunity to collect air samples at special 321 locations. This research was financially supported by the BOF of the Ghent 322 University (project nr B/07601/02). 323 324 References 325 Alvarez, A.J., Buttner, M.P., Stetzenbach, L.D., 1995. PCR for bioaerosol monitoring: 326 sensitivity and environmental interference. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 61, 3639-3644. 327 328 Angenent, L.T., Kelley, S.T., St. Amand, A., Pace, N.R., Hernandez, M.T., 2005. 329 Molecular identification of potential pathogens in water and air of a hospital therapy 330 pool. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102, 4860-4865. 331 332 Aurell, H., Catala, P., Farge, P., Wallet, F., Le Brun, M., Helbig, J.H., Jarraud, S., 333 Lebaron, P., 2004. Rapid detection and enumeration of Legionella pneumophila in hot 334 water systems by solid-phase cytometry. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70, 1651-1657. 335 336 Catala, P., Parthuisot, N., Bernard, L.,Baudart, J., Lemarchand, K., Lebaron, P., 1999. 337 Effectiveness of CSE to counterstain particles and dead bacterial cells with 16 338 permeabilised membranes: application to viability assessment in waters. FEMS 339 Microbiol. Lett. 178, 219-226. 340 341 Chen, P.-S., Li, C.-S., 2005. Bioaerosol characterization by flow cytometry with 342 fluorochrome. J. Environ. Monit. 7, 950-959. 343 344 Cruz, P., Buttner, M.P., 2007. Analysis of bioaerosol samples. In: Hurst, C.J., 345 Crawford, R.L., Garland, J.L., Lipson, D.A., Mills, A.L., Stetzenbach, L.D. (Eds.), 346 Manual of Environmental Microbiology, Ed. 3 , ASM Press, Washington D.C., pp. 347 952-960. 348 349 De Vos, M.M., Nelis, H.J., 2003. Detection of Aspergillus fumigatus hyphae by solid 350 phase cytometry. J. Microbiol. Meth. 55, 557-564. 351 352 De Vos, M.M., Nelis, H.J., 2006. An improved method for the selective detection of 353 fungi in hospital waters by solid phase cytometry. J. Microbiol. Meth. 67, 557-565. 354 355 Dillon, H.K., Miller, J.D., Sorenson, W.G., Douwes, J., Jacobs, R.R., 1999. Review of 356 methods applicable to the assessment of mold exposure to children. Environ. Health 357 Perspect. 107, 473-480. 358 359 Douwes, J., Thorne, P., Pearce, N., Heederik, D., 2003. Bioaerosol health effects and 360 exposure assessment: progress and prospects. Ann. Occup. Hyg. 47, 187-200. 361 17 362 Fracchia, L., Pietronave, S., Rinaldi, M., Martinotti, M.G., 2006. The assessment of 363 airborne bacterial contamination in three composting plants revealed site-related 364 biological hazard and seasonal variations. J. Appl. Microbiol. 100, 973-984. 365 366 Giovannangelo, M.E.C.A., Gehring, U., Nordling, E., Oldenwening, M., van Rijswijk, 367 K., de Wind, S., Hoek, G., Heinrich, J., Bellander, T., Brunekreef, B., 2007. Levels 368 and determinants of ß (13)-glucans and fungal extracellular polysaccharides in 369 house dust of (pre-)schoolchildren in three European countries. Environ. Internat. 33, 370 9-16. 371 372 Gorny, R.L., Reponen, T., Willeke, K., Schmechel, D., Robine, E., Boissier, M., 373 Grinshpun, S.A., 2002. Fungal fragments as indoor biocontaminants. Appl. Environ. 374 Microbiol. 68, 3522-3531. 375 376 Gorny, R.L., 2004. Filamentous microorganisms and their fragments in indoor air - a 377 review. Ann. Agric. Environ. Med. 11, 185-197. 378 379 Green, B.J., Schmechel, D., Kingsley Sercombe, J., Tovey, E.R., 2005. Enumeration 380 and detection of aerosolized Aspergillus fumigatus and Penicillium chrysogenum 381 conidia and hyphae using a novel immunostaining technique. J. Immunol. Meth. 307, 382 127-134. 383 384 Grinshpun, S.A., Buttner, M.P., Willeke, K., 2007. Sampling for airborne 385 microorganisms. In: Hurst, C.J., Crawford, R.L., Garland, J.L., Lipson, D.A., Mills, 18 386 A.L., Stetzenbach, L.D. (Eds.), Manual of Environmental Microbiology, Ed. 3 , ASM 387 Press, Washington D.C., pp. 939-951. 388 389 Joux, F., Lebaron, P., 2000. Use of fluorescent probes to assess physiological 390 functions of bacteria at single-cell level. Microbes Infect. 2, 1523-1535. 391 392 Lange, J.L., Thorne, P.S., Lynch, N., 1997. Application of flow cytometry and 393 fluorescent in situ hybridization for assessment of exposures to airborne bacteria. 394 Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63, 1557-1563. 395 396 Lisle, J.T., Hamilton, M.A., Willse, A.R., McFeters, G.A., 2004. Comparison of 397 fluorescence microscopy and solid-phase cytometry methods for counting bacteria in 398 water. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70, 5343-5348. 399 400 Mignon-Godefroy, K., Guillet, J.-G., Butor, C., 1997. Solid phase cytometry for 401 detection of rare events. Cytometry 27, 336-344. 402 403 Nesa, D., Lortholary, J., Bouakline, A., Bordes, M., Chandenier, J., Derouin, F., 404 Gangneux, J.P., 2001. Comparative performance of impactor air samplers for 405 quantification of fungal contamination. J. Hosp. Inf. 47, 149-155. 406 407 Niemeier, R.T., Sivasubramani, S.K., Reponen, T., 2006. Assessment of fungal 408 contamination in moldy homes: comparison of different methods. J. Occ. Environ. 409 Hyg. 3, 262-273. 410 19 411 Pieckova, E., Jesenska, Z., 1999. Microscopic fungi in dwellings and their health 412 implications in humans. Ann. Agric. Environ. Med. 6, 1-11. 413 414 Prigione, V., Lingua, G., Filipello Marchisio, V., 2004. Development and use of flow 415 cytometry for detection of airborne fungi. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70, 1360-1365. 416 417 Reynolds, D.T., Fricker, C.R., 1999. Application of laser scanning for the rapid and 418 automated detection of bacteria in water samples. J. Appl. Microbiol. 86, 785-795. 419 420 Robine, E., Lacaze, I., Moularat, S., Ritoux, S., Boissier, M., 2005. Characterisation 421 of exposure to airborne fungi: measurement of ergosterol. J. Microbiol. Meth. 63, 422 185-192. 423 424 Stetzenbach, L.D., 2007. Introduction to aerobiology. In: Hurst, C.J., Crawford, R.L., 425 Garland, J.L., Lipson, D.A., Mills, A.L., Stetzenbach, L.D. (Eds.), Manual of 426 Environmental Microbiology, Ed. 3 , ASM Press, Washington D.C., pp. 925-938. 427 428 Stetzenbach, L.D., Buttner, M.P., Cruz, P., 2004. Detection and enumeration of 429 airborne biocontaminants. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 15, 170-174. 430 431 Van Poucke, S.O., Nelis, H.J., 2000. Rapid detection of fluorescent and 432 chemiluminescent total coliforms and Escherichia coli on membrane filters. J. 433 Microbiol. Meth. 42, 233-244. 434 20 435 Venkateswaran, K., Hattori, N., La Duc, M.T., Kern, R., 2003. ATP as a biomarker of 436 viable microorganisms in clean-room facilities. J. Microbiol. Meth. 52, 367-377. 437 438 Vermis, K., Vandamme, A.R., Nelis, H.J., 2002. Enumeration of viable anaerobic 439 bacteria by solid phase cytometry under aerobic conditions. J. Microbiol. Meth. 50, 440 123-130. 441 442 Wu, F.Q., 2007. Culture-based analytical methods for investigation of indoor fungi. 443 In: Yang, C.S., Heinsohn, P.A. (Eds.) Sampling and analysis of indoor 444 microorganisms. John Wiley & Sons, New Jersey, pp 105-122. 445 446 Zhang, T., Fang, H.H., 2006. Applications of real-time polymerase chain reaction for 447 quantification of micro-organisms in environmental samples. Appl. Microbiol. 448 Biotechnol.70,281-289. 21 Fig.1: Comparison between the number (CFU m-3) of micro-organisms detected after sampling of different volumes of air on TSA and subsequent incubation at 20°C for four days (error bars present SE). Fig.2: Ratios between the total number of cells detected with SPC and the number of CFU on TSA with the culture-based method in air sampled at various locations. The numbers correspond to the locations in Table 1 and 7 values (light grey) are presented using a different scale. (error bars present SE). 22 Table 1: Plate counts and SPC counts in air sampled at different locations Microbial population as determined by: Filtered volume Sampling (SPC) (ml) volume (l) Location SPC counts CFU-1 SE Culture-based method (Mean CFU m-3 SE) Solid phase cytometry (SPC) (Mean cells m-3 SE) TVC Fungi Total (TSA) Bacteria (TSAc) Fungi (RBCA) Total (tvc-protocol) Bacteria (tvc-protocol) Fungi (fungi-protocol) Total Bacteria Fungi 1. Laboratory 1 100 9 9 353 38 150 6 173 15 1533 59 807 52 593 41 4.34 0.50 * 5.38 0.41 * 3.42 0.38 * 2. Laboratory 2 100 9 9 107 18 77 9 57 3 319 27 178 22 185 45 2.99 0.56 * 2.32 0.40 * 3.27 0.81 * 3. Laboratory 3 100 9 9 150 20 57 9 97 19 289 34 133 22 148 27 1.93 0.34 * 2.35 0.54 * 1.53 0.41 4. Living room 100 9 9 320 6 110 20 b 177 23 578 97 230 37 333 34 1.81 0.31 * 2.09 0.51 1.89 0.31 * 5. Bedroom 100 9 9 480 32 273 62 150 21 837 39 348 49 622 154 1.74 0.14 * 1.27 0.34 4.15 1.18 * 6. Kitchen 100 9 9 350 92 370 50 340 29 526 129 326 78 281 93 1.50 0.54 0.88 0.24 0.83 0.28 7. Hall 100 9 9 300 30 183 35 47 18 274 7 156 22 163 58 0.91 0.09 0.85 0.20 3.49 1.83 8. Student room 100 9 9 440 15 323 15 53 19 667 46 370 45 156 38 1.52 0.12 * 1.15 0.15 2.92 1.26 9. Office 1 100 9 9 1130 47 627 42 273 28 4615 3416 2867 2256 311 26 4.08 3.03 4.57 3.61 1.14 0.15 10. Office 2 100 9 9 1310 136 213 35 560 44 1000 198 563 162 326 78 0.76 0.17 2.64 0.87 * 0.58 0.15 * 100 9 9 387 30 173 30 53 7 1422 198 511 78 2119 90 3.68 0.59 * 2.95 0.68 * 39.72 5.48 * 12. False ceiling (office) 100 9 9 723 50 597 57 33 15 467 59 185 39 96 30 0.65 0.09 * 0.31 0.07 * 2.89 1.58 * 13. Bathroom 1 100 9 9 1050 191 427 26 47 12 541 109 252 45 326 95 0.51 0.14 * 0.59 0.11 * 6.98 2.71 * 14. Bathroom 2 100 9 9 1637 56 2157 141 603 98 3963 426 3111 386 689 64 2.42 0.27 * 1.44 0.20 1.68 0.43 15. Toilet 100 9 9 553 12 447 33 290 10 704 37 400 26 304 32 1.27 0.07 * 0.90 0.09 1.05 0.12 Car 100 (airconditioning off) 9 9 2787 232 550 50 810 40 9319 7747 7874 6935 593 41 3.34 2.79 14.32 12.68 0.73 0.06 * 11. 16. False (kitchen) ceiling 23 17. Car 100 (airconditioning on) 9 9 473 111 343 83 253 27 719 291 533 280 185 63 1.52 0.71 1.55 0.90 0.73 0.26 18. Student hall 100 9 9 807 159 583 27 257 45 756 67 430 53 600 89 0.94 0.02 0.74 0.10 2.34 0.54 * 19. Student restaurant 100 9 9 19207 60 163 22 230 21 444 64 222 22 281 15 1.68 0.45 * 1.36 0.23 1.22 0.13 1443 52 4400 814 2067 412 1719 262 1.30 0.27 1.04 0.22 1.19 0.19 141 63 89 22 104 7 1.21 0.56 1.16 0.32 1.83 0.41 * 20. Station (entrance hall) 100 9 9 3373 334 1990 142 21. Station (platform) 100 9 9 117 13 77 9 22. Swimming pool 1 100 9 9 410 159 140 10 37 19 1889 328 1148 161 348 119 4.61 1.96 * 8.20 1.29 * 9.49 5.89 * 23. Swimming pool 2 100 9 9 700 61 330 50 50 10 3311 2445 2422 1889 96 53 4.73 3.52 7.34 5.83 * 1.93 1.13 24. Parking outdoor 100 9 9 1747 20 80 0 1167 24 1600 78 578 13 1067 84 0.92 0.05 7.22 0.16 * 0.91 0.07 57 12 25. Outdoor environment 1 100 9 9 293 28 83 19 73 9 837 71 407 52 311 64 2.85 0.36 * 4.89 1.28 * 4.24 1.02 * 26. Outdoor environment 2 100 9 9 300 46 137 23 143 15 696 39 341 7 304 15 2.32 0.38 * 2.49 0.42 * 2.12 0.25 * 100 9 9 747 27 340 36 463 23 2481 334 1511 244 1074 52 3.32 0.46 * 4.44 0.86 * 2.32 0.16 * 28. Botanical garden 1 100 9 9 1130 60 223 22 657 35 3163 924 1985 763 948 7 2.80 0.83 * 8.89 3.53 * 1.44 0.08 * 29. Botanical garden 2 100 9 9 3020 150 220 25 3320 121 2793 1526 941 686 8941 1303 0.92 0.51 4.28 3.16 2.69 0.40 * 30. Botanical garden 3 100 6 9 980 a 193 24 353 101 9344 2024 6344 1367 778 223 9.54 2.07 32.82 8.16 * 2.20 0.89 31. Botanical garden 4 100 6 9 757 101 147 9 437 22 1211 78 722 80 333 71 1.60 0.24 * 4.92 0.62 * 0.76 0.17 27. Park 32. Pigs stable 1 (ground-level) 100 0.1 6 NC 6.6 104 2.6 104 567 70 7.9 104 5.0 104 7.5 104 5.0 104 1022 111 - 1.14 0.76 1.80 0.30 * 33. Pigs stable 1 (1m high) 100 0.1 6 NC 1.4 105 8.9 103 580 21 7.1 105 3.0 104 7.1 105 3.0 104 1011 156 - 4.89 0.36 * 1.74 0.28 * 34. Pigs stable 2 (ground-level) 100 0.1 6 NC 6.0 104 1.3 104 580 31 1.2 105 3.3 104 1.2 105 3.3 104 1244 238 - 1.99 0.70 2.15 0.43 * 35. Pigs stable 2 (1m high) 100 0.1 6 NC 6.2 104 3.8 103 530 17 1.6 105 3.1 104 1.6 105 3.1 104 1733 204 - 2.51 0.52 * 3.27 0.40 * 10 1 9 1.4 105 1.1 105 1.3 104 1.3 103 1767 186 -d -d 9506 428 - - 5.38 0.61 * 36. Pigs stable 1 24 37. Pigs stable 1 100 0.1 6 1.7 104 1.2 104 5210 377 887 115 8.0 105 5.1 105 7.8 105 5.0 105 9922 6732 45.94 43.12 * 149.64 97.05 * 11.19 7.73 * 38. Pigs stable 2 10 1 9 1.7 106 1.4 105 1.7 106 2.2 105 6033 2459 9.4 105 7.3 104 9.3 105 7.2 104 1.2 104 3.9 103 0.57 0.06 * 0.56 0.08 * 1.98 1.04 39. Pigs stable 2 100 0.1 6 2.3 105 2.4 104 2.6 105 1.9 104 2550 953 8.1 105 1.8 104 7.3 105 2.8 104 5078 1281 3.50 0.38 * 2.85 0.23 * 1.99 0.90 40. Pigs stable 3 100 0.1 6 1.8 104 7.2 103 b 4.0 104 4.6 103 2403 58 3.6 105 1.8 105 3.6 105 1.8 105 4622 1848 20.02 12.72 9.04 4.78 1.92 0.77 41. Chicken stable 1 10 0.1 6 3.9 106 1.8 106 5.2 106 4.5 105 2000 265 -d -d 1667 333 - - 0.83 0.20 42. Chicken stable 2 10 0.1 6 5.9 106 1.4 105 6.0 106 4.5 105 1233 120 -d -d 778 111 - - 0.63 0.11 43. Chicken stable 100 outdoor environment 1 6 1363 47 420 67 143 66 -d -d 600 484 - - 4.19 3.89 44. Animalarium 1 (during activity) 100 9 9 470 32 367 15 57 9 3563 376 2748 175 711 270 7.58 0.95 * 7.49 0.57 * 12.55 5.16 * 45. Animalarium 2 (after activity) 100 9 9 220 26 63 30 23 9 719 131 548 119 222 13 3.27 + 0.71 * 8.65 4.51 * 9.52 3.72 * 46. Animalarium 3 (before activity) 100 9 9 1157 35 787 94 30 12 2822 167 1622 139 489 34 2.44 0.16 * 2.06 0.30 * 16.30 6.62 * 47. Animalarium 4 (before activity) 100 9 9 1087 112 760 95 270 67 1622 56 1059 82 526 45 1.49 0.16 * 1.39 0.20 * 1.95 0.51 * 48. Clean-room (class 1000) 100 9 9 20 20 30 6 00 1233 1100 b 1044 978 b 67 44 61.67 82.63 34.81 33.34 66.67 76.98 * 49. Clean-room (class 10000) 100 9 9 33 19 33 9 33 207 85 185 74 30 20 6.22 4.37 * 5.56 2.68 * 8.89 10.00 50. Clean-room (class 100000) 100 9 9 73c 94c 00c 256 164 c 234 152 c 49 13 c 38.45 30.08 * 28.02 22.66 * 48.73 13 * NC: not countable *: statistically significant difference between results obtained by the culture-based method and by SPC (Mann-Whitney test, p < 0.05) a : result based on only 1 value b : result based on only 2 values c : result based on 6 values d : scan aborted 25 Table 2: Remaining viable cells after storage (4°C) of the dissolved Polym’air for 4 h and 24 h. Data are presented as the average fraction (%) of the cells that were detected at t = 0 ( SE). Storage time 4h 24 h Fraction of the cells (%) detected at t = 0 Bacteria Total Fungi 104 3 112 23 106 1 43 15 * 51 13 * 53 25 * *: statistically significant difference between results obtained before and after storage (Mann-Whitney test, p < 0.05)