Conference 2008 Magazine Report

advertisement

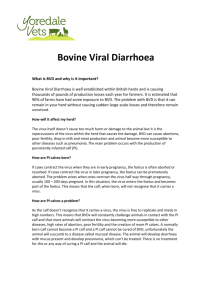

Camelid Health and Alpaca Fabrics Claire Waring reports on the British Camelids Conference On 25 October 2008, camelid owners from all over the British Isles gathered at The Stoneythorpe Hotel, Southam, Warwickshire, for a day conference organised by British Camelids Ltd (BCL), the charity supported by the British Alpaca Society and the British Llama Society for camelid welfare and the education of camelid owners. As part of its remit, BCL sponsored two vets, Robert Broadbent and Peter Aitken, to attend the International Camelid Conferences in 2007 and 2008, respectively. They took the opportunity to update everyone. Both conferences had given the chance to learn up-to-date information from leading camelid vets worldwide. Robert Broadbent reported on bovine viral diarrhoea (BVD) and TB in camelids. The commonest form of BVD is transient infection in both adults and cria. They can shed virus particles for under three weeks. An overt infection for 3–5 days is possible but uncommon. Very rarely, animals suffer a chronic infection. It may take 21–28 days to clear the virus from the bloodstream and antibodies are usually found within10 days of infection. Originally it was thought that camelids were 'resistant' to BVD but this has now been shown not to be the case and the incidence of the disease in camelids is increasing because of the emergence of a new unique pestivirus affecting them. Some 3–5 per cent of infected animals do not become ill. Sheep, goats and deer can all carry BVD with no ill effects to the animals concerned. It is important to distinguish between animals that have the virus and those with antibodies. The latter are immune to BVD and cannot carry the virus. In very rare cases, an immune male bull has been known to carry the virus in the testicles. There can be early reproductive losses in cria that are termed 'Persistently Infected' or PI. If a dam is infected in early pregnancy (32–150 days), there is an 82 per cent chance her cria will be PI. Most PI cria appear normal at birth although they may be slightly underweight. PI cria are unable to get rid of the virus and are likely to continue shedding virus particles, and thus infecting the rest of the herd. If the herd is tested and all animals are shown to carry antibodies, they cannot become infected. Any testing positive for the virus should be removed so that the herd remains 'BVD free'. PI cria are generally 'poor doers' and can have intermittent diarrhoea. They are susceptible to infections and infestations. Huacaya cria can develop a suri-like fleece with a large amount of guard hair and they usually die at under 30 months, some very suddenly. In camelids, the virus is transmitted in saliva, but this is not seen in cattle. This could indicate that the virus is evolving and adapting to camelid behaviour. Investigations are ongoing into possible spread via other tissues and fluids. Owners can help prevent spread of BVD with good biosecurity and by taking care when mixing and moving animals. In the USA, one large herd tested every animal and culled any that tested positive for the virus, even if this included top breeding stock. Animals were tested again after six months and any that did not have antibodies were culled. This included those not testing positive for either the virus or antibodies as it was not known whether these animals were infected or not. Thus all remaining animals showed antibodies and they were immune to BVD, giving the first US herd that could claim to be BVD-free. It had a huge marketing advantage and subsequently, the rest of the industry followed suit. Camelid owners in the UK were advised that the only reliable test for virus particles is the PCR test. Tests for BVD in other species cannot be used in camelids with absolute certainty. Owners were strongly advised to avoid using unlicensed vaccines as their mechanism is unknown and will confuse future serological tests by possibly stimulating antibody production. They were warned that BVD can be spread with very few particles and that it can be transmitted from cattle to camelids. Robert continued with information about TB in camelids, reporting that this is generally caused by Mycobacterium bovis (M. bovis). If camelids are infected, it is usually by the same type as found in local cattle and types can be specific to very small geographical areas. TB is prevalent in the south west of England and is spreading. Spread and reappearance are often seen in Meles meles (the badger) at the same time. The organism can be present in urine, sputum, faeces, milk or discharges and is spread by ingestion or inhalation. Work in New Zealand has indicated that TB can be controlled even when the wildlife vector is present if the situation is tackled on a regional basis. Cattle, badgers and camelids are all inquisitive animals and will make nose-to-nose contact, and most spread is by inhalation. Robert commented that it is virtually impossible to catch TB in the aerosol form from droppings. Often the only indication of TB infection is respiratory but dull or dead areas make listening to the chest difficult. Animals may show progressive loss of weight or muscle mass. The disease may be chronic and prolonged with animals showing few, if any, signs of infection, or it can be peracute with animals dying very quickly, sometimes within two months. Most animals exposed to M. bovis get over the infection and then become immune. Diagnosis is with the Comparative Intradermal Skin Test (CIDT) and this is the only test that Defra will use in case they are subject to a legal challenge. The Chem-Bio test can be used and the company is currently developing a new STAT-PAK snap test. An interferon-gamma test is being investigated at Weybridge. This is very species-specific and a llama test could be available within a couple of years if suitable funding is forthcoming. CIDT is highly specific and if it is positive then the animal will be taken by Defra to be infected, even if other tests are negative. If the skin test is confirmed positive, Defra will allow the rest of the herd to be tested with the Chem-Bio test and any animals then testing positive will be culled. The skin test cannot be repeated for 60–90 days and it appears that for camelids the second test should be after 90 days. Because of government policy it is unlikely that there will be a badger cull in England. A study of bovine TB (bTB) in a random sample of healthy badgers in 2004–2008 indicated that over 24 per cent were affected by TB. Because the cost of a detailed examination is prohibitive, latent infections are undetected. As the disease progresses in badgers, their behaviour alters and they spend more time away from the sett. A limited cull is not effective as badgers from outside the cull area move into the empty setts. However, there is evidence that this does not occur with a more extensive cull. Owners were reminded that camelids can pass TB to humans, particularly through nose-to-nose contact. Treatment for TB is expensive, protracted and often ineffective so the disease is controlled by detection and slaughter. Camelids with TB can show unexplained weight loss. They may also exhibit breathing difficulties. TB can affect any apparently completely normal animal of any age and even one which passes the skin test. In Wales, all bovines and camelids are to be skin tested. The Welsh Assembly will offer compensation of up to £1500. A consultation paper is currently under review. In England, Defra is considering compulsory testing of other animals only when one has tested positive. Its compensation level is currently £750. The European Union requires every Member State to put a TB eradication programme in place and the Welsh Assembly will pursue its plans rigorously with implementation of border controls. Robert urged the camelid industry to be proactive and take the initiative. There is currently no TB vaccine available for cattle or camelids. The number of possible cases is rising and there is a very high level of camelid movements within the UK without any required pre- or post-movement testing or standstills. Peter Aitken had attended the 2008 conference and began by illustrating that it wasn't all serious lectures by showing pictures of musical chairs played with llamas! His first topic was plasma. Although antibodies are the main benefit of plasma, other protein factors found in it are also useful. It is most needed when there is failure of passive transfer (FPT) of antibodies from dam to cria. This can occur in both healthy and sick cria and two units can be required to achieve the necessary IgG level. In general, abnormal cria show a higher incidence of FPT. The commonest reason for FPT is poor nutrition of the dam. The colostrum forms about one week before the birth so the dam needs to be well fed at this time. Plasma collection is not complicated and is usually done from castrated males. It is best to use plasma collected from within the herd and, as an animal product, plasma should not be sold unless clearance has been obtained from the Veterinary Medicines Directorate. Powdered camelid colostrum is available for emergencies but plasma is preferred. Colostrum is ineffective if given more than 24 hours after birth. Peter continued his presentation by dealing with gastrointestinal parasitism. Camelids are susceptible to all major parasites affecting cattle and sheep but there is no excuse for the infestation to become severe enough to kill the animal. Veterinary advice should be sought if an animal becomes infested. Worms are becoming resistant to avermectin products which suggests that wrong dosages are being used. It was suggested that faecal egg counts be made annually with a second count taking place 10 days after drenching to check that this has been effective. When testing, owners were advised to ask for the sensitive test which checks for 10 eggs/gm. Fluke is checked with a separate test which must be asked for specifically. Pour-ons are considered ineffective as those designed for sheep rely on the lanolin in the wool in order to work. Injectables are effective but care must be taken not to underdose. Worm larvae only crawl about 3–4 mm up the sward so keeping the residual pasture higher than this will help to reduce larval intake by grazing animals. Daily cleaning of the nursery pasture will also help but will not pick up all the larvae as they spread out from the faeces. Peter's final topic was Bluetongue (BTV), endemic in Africa and transmitted by five species of the Culicoides midge. In the UK, a dead vaccine has been developed and licensed for cattle and sheep. Here the regime is two initial doses with six-monthly boosters. A trial has been done to assess the efficacy of the blue tongue vaccine and preliminary results show that it has been worth doing although further information is due shortly. Vaccination can be given from one month of age. This vaccine is only effective for BTV8 and provides no protection against other strains. BTV1 and BTV6 have been confirmed on the Continent. Everyone was urged to vaccine their herd against Bluetongue as this is the only control available. They were also urged to think very carefully before importing animals, especially from France and Holland. The good news is that around 90 per cent of all target species within the England and Wales Protection Zone have been vaccinated. Owners were encouraged to work vaccination into their management programme. Joint Action against Bluetongue (JAB) is asking all owners to order sufficient vaccine from their vets now so that the vet can obtain sufficient supplies ready for the start of vaccination in March/April. The final lecture was something completely different as Angela Martin, a freelance design historian, took a look through the history of the use of alpaca. When Titus Salt found the first alpaca fibre in a Liverpool warehouse in the 1930s, he recognised its potential qualities. By 1835 he has solved the problems with spinning the fibre with cotton and, by 1837 with silk. He and John Foster, a Bradford textile manufacturer, shared the alpaca industry and monopolised imports. At the peak of production, Fosters produced 4500 miles of cloth per year and Titus Salt was producing 18 miles a day at his mill in Saltaire. The latter was primarily but not wholly alpaca. At the Great Exhibition in 1851, Salt claimed that virtually all of the Peruvian clip was being processed in Bradford and the cloth was being exported worldwide. In 1844, Queen Victoria and Prince Albert were given two alpacas. Sadly the black one died but Victoria had the fleece made up into cloth and this was reported in The Times on 14 December. Alpaca was widely used but usually as a mixture. Garments included crinolines, men's cloaks and children's clothing and alpaca was also used for furnishings. In 1854, Sanosters sold 45,000 black alpaca umbrellas! Angela showed pictures of lovely dresses made in wonderful colours. At the end of Spanish colonial rule with Peru's independence in 1821, Britain was trading with the country both legally and illegally. Queen Victoria declined the Crown of Peru as it was more profitable to trade than to run the country. The final discussion of the day covered biosecurity and was based on a paper from Claire Whitehead. The aim is to prevent the introduction and spread of disease in susceptible animals. Biosecurity is achieved by preventing potential pathogens (parasites, bacteria, viruses, etc) coming on to the farm. If they are on the farm then their spread must be halted. The risks to biosecurity come from livestock movements – sales, breeding, showing, trekking, socialising and movement to fresh grazing. This could lead to the conclusion that everything should be stopped immediately! Practically, contact with unhealthy looking animals should be avoided. Record the current and past health status of animals on the farm and follow all vaccination and parasite control protocols. If necessary, ask the vet about disease testing protocols and look for any ways in which the herd health status can be improved. There is little doubt that pre-movement testing will be introduced. It is advisable to isolate and quarantine any animals that have previously mixed with others. Paired samples for tests should be kept for 40 days after an animal has left the farm, one at the original location and the other at the destination. This helps to track back to the origin of a disease if necessary. A 30-day postmovement standstill is recommended in order for any parasite problems to become apparent. Above all, owners should practice common sense and be aware that people, including other owners and vets, and vehicles can carry disease. Owners need to asses the risks to their animals and at least take simple precautions. BCL is to be congratulated on a very successful, informative conference and I am sure that all those attending went away with plenty of new information and food for thought.