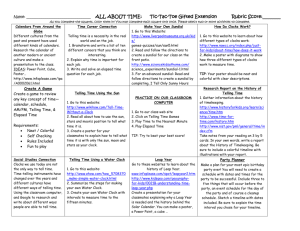

Shadows Text Resource

advertisement

History of Sundials The earliest record of the sundial dates back as early as 3500 BCE. At this time the ancient Egyptians were building tall, slender monuments from stone, called obelisks, which cast shadows that functioned like a sundial. Obelisks enabled people to divide the day into morning and afternoon, and they also showed the longest and shortest days of the year when the shadow they cast was longest or shortest at noon. Later on, additional markers were added around the base of the obelisk to indicate further subdivisions of time. Possibly the first portable timepiece came into use around 1500 BCE. Still a sundial, this was another Egyptian invention and it divided the day into ten parts plus two “twilight hours” in the morning and evening; was this the origin of the “twelve hour day” that we know today? Around 600 BCE the Egyptians came up with another invention, the merkhet (the oldest known astronomical tool), which allowed them to tell the time at night when there was no sun to cast a shadow. The merkhet worked in a similar way to a sundial: you would line up a pair of them in a north-south direction using the Pole Star, and then as certain stars crossed that line you would be able to tell what time it was. In the pursuit of year-round accuracy sundials gradually developed from their original shape, of a flat or vertical plate or surface, to much more elaborate forms. One version was a bowl-shape, cut into a block of stone, with a central vertical pointer (gnomon) whose shadow fell on lines marking sets of hour lines for different seasons. Around 300 BCE this idea was developed further into a half-bowl shape, cut into the edge of a squared block and called the ‘hemicycle’. In the 2nd century BCE the mathematician and astronomer Theodosius of Bithynia was said to have invented a universal sundial that could be used anywhere on Earth. By 30 BCE Vitruvius, a Roman writer, architect and engineer, was able to describe 13 different types of sundial in use throughout Greece, Asia Minor (Turkey) and Italy. By the 16th century astronomers were publishing treatises on sundials, explaining how they worked, how to manufacture them and how to set them up either vertically or horizontally. Sundials have to be lined up in certain directions, depending on what hemisphere you are in and according to the axis of the Earth’s rotation: that is, the end of the gnomon should point north if you are in the northern hemisphere (where Britain is), or south if you are in the southern hemisphere. © Original resource copyright Hamilton Trust, who give permission for it to be adapted as wished by individual users. Y3 Sc Light – Session E How a Sundial Works A very basic sundial can consist of a stick pointing upwards from a flat surface. As the Sun rises and sets, the shadow from the stick can be seen on the flat surface. The shadow will go round in a clockwise direction and the position of the shadow can help us tell the time. It is believed that this is why our modern clocks have hands, which go round the same way. At noon, when the Sun is at its highest point, the shadow from your pointer (the gnomon) will point north if correctly positioned. From this, you can work out other times! © Original resource copyright Hamilton Trust, who give permission for it to be adapted as wished by individual users. Y3 Sc Light – Session E Making a Sundial You will need: card ruler compass flat piece of wood (or thick card) glue or sticky tape protractor scissors pen What you do: 1. Draw the outlines of two marker shapes on to the cardboard and cut them out (52 degree triangles with an extra 2.5cm along the base for folding back and sticking). 2. Score a line 2.5cm in from the base of the triangle (long side) and fold back along the line. 3. Stick the two shapes back to back, leaving the 2.5cm section sticking out on both sides (these will be used to glue the marker down on to the wood and to give it stability). 4. Draw a half circle on a piece of wood (same radius as length of marker). 5. Stick the marker down the middle of the semicircle, leaving a quarter circle on each side. 6. Using a compass, point the marker towards the south and position the sundial on a flat surface. © Original resource copyright Hamilton Trust, who give permission for it to be adapted as wished by individual users. Y3 Sc Light – Session E 7. Mark the position of the shadow cast by the sun on the semicircle every hour, on the hour. Enlarge and Photocopy to make marker template: © Original resource copyright Hamilton Trust, who give permission for it to be adapted as wished by individual users. Y3 Sc Light – Session E © Original resource copyright Hamilton Trust, who give permission for it to be adapted as wished by individual users. Y3 Sc Light – Session E Make a Simple Sundial You will need: Plasticine Two rulers Sun Take a ruler and make it stand on its edge using Plasticine feet! Place another ruler next to it. Make sure that 0cm is closest to the upright ruler. (You really need a ruler where 0 is marked on the end if possible). Watch as the sun creates a shadow on flat ruler. Record the length of the shadow. Note as the shadow shortens and lengthens during the day. There you have it: a portable sundial. © Original resource copyright Hamilton Trust, who give permission for it to be adapted as wished by individual users. Y3 Sc Light – Session E