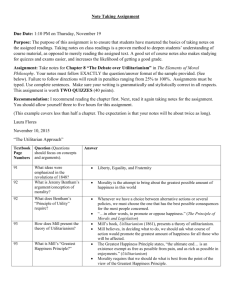

OUTLINE of Mill`s Utilitarianism

advertisement

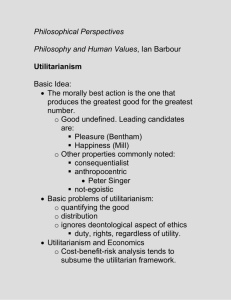

OUTLINE OF J.S. MILL’S UTILITARIANISM CHAPTER I – General Remarks 205,1 There are few areas in which there is a greater lack of unanimity than the question of the foundation of morality. 205,2 A similar confusion exists regarding the foundations of the sciences. Luckily, progress in the sciences doesn’t depend on this. 206,2 Our moral faculty supplies us only with the general principles of moral judgments. There is general agreement that morality must be deduced from principles. There ought to be some one fundamental principle or set of principles at the root of all morality. 207, 2 Despite the lack of agreement on what the principle is, it is easy to show the tacit influence of a standard not recognized, the greatest happiness principle. At least everybody admits that human happiness is of prime consideration as a basis for morality. 207, 3—208, 1 I will now try to give “the Utilitarian or Happiness theory” such proof as it is possible to attain. This should enable us to decide whether to give or withhold assent to the theory. 208, 2 In order to do this, I must explain what Utilitarianism is and what rational grounds can be given for accepting it. CHAPTER II—What Utilitarianism Is 209, 1 “Utility” and “pleasure” are not opposed to each other, despite the common misconception. 210, 1 To speak of utility as the foundation of morals is to assert the greatest happiness principle, and happiness means pleasure and the absence of pain. 210, 2 To some people, this seems to reduce human life to the level of pigs. 210, 3 But, as the Epicureans have always answered, human pleasures are on a much higher level than those of pigs. These include “pleasures of the intellect, of the feelings and imagination, and of the moral sentiments [italics added].” 211, 1 We should not rely on the Epicureans alone for our theory. Many Stoic and Christian elements need to be added. But clearly, some kinds of pleasure are inherently more desirable and more valuable than others. 211, 2 But how are we to decide which kinds of pleasures are higher and which are lower? Ask the people who are familiar with all the kinds listed. Outline of J.S. Mill’s Utilitarianism 2 211, 3—212, 1 “It is better to be a human being dissatisfied than a pig satisfied; better Socrates dissatisfied than a fool satisfied.” And this is—by and large—the consensus of mankind. 212, 2—213, 1 Granted that at times people yield to their lower impulses. In general, the people who know both prefer the higher. 213, 2 “From this verdict of the only competent judges…there can be no appeal.” 213, 3—214,1 In any case, we base this judgment on the common, rather than the individual good. 214, 2 Sums up the preceding paragraphs. 214, 3 In opposition to the view just stated, some people argue that happiness cannot be our end, a) because it is unattainable and b) because we are unworthy of it. 214, 4—215, 1 But human happiness doesn’t have to be perfect or ecstatic. He defines it as “an existence made up of few and transitory pains, many and various pleasures, with a decided predominance of the active over the passive, and having as the foundation of the whole, not to expect more from life than it is capable of bestowing.” 215, 2—216,1 He answers objections: great numbers of mankind have been satisfied with much less than the above. “The main constituents of a satisfied life appear to be…tranquility, and excitement.” When those “who are tolerably fortunate in their outward lot” complain, it is because of “selfishness and want of mental cultivation.” 216, 2—217,1 There is no reason why the happy life just described shouldn’t be available to “everyone born in a civilized country…[M]ost of the positive ills of the world are in themselves removable…Poverty may be completely extinguished…[D]isease may be indefinitely reduced…[by] the progress of science….All the grand sources…of human suffering are in a great degree, many of them almost entirely, conquerable by human care and effort…” 217, 2 “Unquestionably it is possible to do without happiness; it is done involuntarily by nineteen-twentieths of mankind…, but this is not as it should be. 217, 3—218, 1 can inspire. 218, 2 Self-sacrifice for others is noble and the Stoics show the tranquility it While self-sacrifice is noble, it is not in itself good. 218, 3—219, 1 The Golden Rule, Christianity, et al. instill the common interest of the individual and society. Outline of J.S. Mill’s Utilitarianism 3 219, 2—220, 1 Ninety-nine percent of our actions are done for motives other than duty. We must not forget to distinguish the morality of an action from the moral worth of the agent. He provides an implied standard for judging the moral worth of our actions, based on whether or not they can be generalized. This suggests a continuum from act utilitarianism through rule utilitarianism to Kant’s categorical imperative. 220, 2—221, 1 While we don’t want to confuse the value of an action with the moral worth of the person who does it, “in the long run the best proof of a good character is good actions.” 221, 2—222, 1 But don’t expect unanimity. Even Utilitarians disagree about the morality of actions as measured by their own standard. 222, 2—223, 1 Is Utilitarianism godless? Surely God desires human goodness and happiness, but “we need a doctrine of ethics carefully [worked] out, to interpret [his will to us].” 223, 2 He then makes his strongest statement of Rule Utilitarianism in rebutting the accusation that Utility means only Expediency. With telling the truth as his example, he describes the deep human need to be treated ethically as “transcendent expediency.” In thus redefining expediency, he sounds a lot like Kant, except that, in contrast to Kant’s inflexibility, Mill permits exceptions to moral imperatives when circumstances make them necessary. 224, 1—225, 1 Like any ethical system, Utilitarianism requires intermediate rules to get from its general principles to specific actions. But we shouldn’t be silly enough to think that human society hasn’t built up at least a modest store of practical moral wisdom. Utilitarianism draws on this and develops its own intermediate rules based on it, and thereby provides a clearer explanation of traditional rules. 225, 2—226, 1 Like all systems, Utilitarianism faces difficult and exceptional cases, as well as individuals who don’t live up to the standard it sets. But judge it on its merits, compared with other systems, in deciding difficult questions. CHAPTER THREE Of the Ultimate Sanction of the Principle of Utility 227, 1 It is hard to provide a new foundation for traditional, customary morality. 227, 2 This will continue until improved education creates a greater feeling of unity with our fellow creatures. Outline of J.S. Mill’s Utilitarianism 4 228, 2 People desire the approval of others and of God. The resulting system of rewards and punishment provide external sanctions of human behavior. There is no reason why these motives shouldn’t attach themselves to Utilitarianism. 228, 3—229,1 Then there is the internal sanction of duty, as expressed in conscience, the pain attendant on violation of our duty. 229, 2 The ultimate sanction of all morality is this subjective feeling of conscience. 229, 3—230, 1 He attempts to rebut Kant on the nature of our sense of duty, asserting that it is a subjective feeling and that its strength or weakness is independent of Kant’s epistemology. 230, 2 On the other hand, if Kant’s “transcendental” basis of morality reinforces conscience, so much the better for Utilitarianism. 230, 3 Moral feelings are not innate, but are the natural outgrowth of our nature. However, they are subject to a wide variety of good and bad influences. 230, 4—231, 1 If there were no natural basis for Utilitarianism, it might well be rebutted or ignored. 231, 2—232, 1 But there is a firm basis—the social feelings of mankind, which tend to be democratic. That is, as much as circumstances permit, we tend to treat each other as equals. In this regard, when he speaks of “the contagion of sympathy,” he sounds like Hume, adding that “[A]n improving state of the human mind” tends to increase our sense of unity with other human beings. He tries to make a kind of religion out of this sense, with or without a belief in God. 233, 1 “In the early state of human advancement in which we now live,” the feeling of unity with the rest of humanity is only partly developed and subordinate to selfish feelings. But it is “the ultimate sanction of the greatest-happiness morality.” CHAPTER IV Of What Sort of Proof the Principle of Utility Is Susceptible 234, 1 First principles are not proven, but are discovered in sense-experience or in our minds. 234, 2 How then can the Utilitarian principle of happiness “make good its claim to be believed”? 234, 3 How do we know that happiness is desirable? Because the mass of mankind desire it. This is all the proof we can have, but it’s also all the proof we need. “Happiness Outline of J.S. Mill’s Utilitarianism 5 has made out its title as one of the ends of conduct, and consequently one of the criteria of morality.” 234, 4—235, 1 But what about other ends, like virtue, that people desire and aim for? 235, 2 Virtue, music, health, etc. are desirable in themselves; they are means to happiness, but are also parts of happiness itself. 235, 3—236, 2 Thus, “the means have become part of the end….Happiness is not an abstract idea…” 236, 3—237, 1 Virtue is the highest of these qualities. It is “above all things important to the general happiness.” 237, 2 “Those who desire virtue for its own sake, desire it either because the consciousness of it is a pleasure, or because the consciousness of being without it is a pain.” 237, 3 “[H]uman nature is so constituted as to desire nothing which is not either a part of happiness or a means of happiness…If so, happiness is the sole end of human action, and…the criterion of morality.” 237, 4—238,1 The desirable and the pleasant are equivalent. 238, 2—239, 1 Will is not essentially different from desire. Desire is a passive mental state, and will an active one. It is desire generalized and made active. The virtuous will springs from the desire to be virtuous. The virtuous will is “a means to good, not intrinsically a good” and does not contradict the idea that happiness is our sole end. 239, 2 Thus we have the proof of the principle of utility. CHAPTER FIVE On the Connexion between Justice and Utility 240, 1 Justice has always been conceived of as divorced from Utility or Happiness; hence the concept of justice has always been one of the strongest obstacles to the acceptance of Utilitarianism. 240, 2—241, 1 A sense or feeling of justice seems to be bestowed on us by nature. People tend to think it has a totally different origin than expediency or utility. To investigate this subject, we need to ask whether justice is an irreducible idea that we have or a composite one? 241, 2 What is the distinguishing characteristic or characteristics of justice? Is it or are they always present in it or is the sentiment inexplicable? Outline of J.S. Mill’s Utilitarianism 241, 3—244, 1 6 He groups the attributes of justice under six headings: 241, 4 It is unjust to violate liberty or legal rights 242, 2 It is unjust to deprive people of something to which they have a moral right. 242, 3 Everybody should obtain what they deserve, and not what they don’t. 242, 4—243,1 expectations It is unjust to break faith: to break a promise or disappoint 243, 2 It is injust to show partiality. 243, 3 Allied to impartiality is equality, i.e. giving people equal treatment 244, 2 How are all these different senses connected? 244, 3—245, 1 He gives etymologies (word origins) from various languages (Latin, Greek, German, and French) of the word ‘justice.’ “[T]he primitive element…in the formation of the notion of justice…was conformity to law.” 245, 2—246, 1 This concept of justice has been extended to activities not regulated by statutes or courts. 246, 2 We call an action wrong if people should be punished for doing it. Duty is what we may right be compelled to do. 246, 3—247, 1 He explains the distinction between perfect and imperfect obligations. In the latter case, the particular occasions are left to our choice. “[T]his distinction exactly coincides with that which exists between justice and the other obligations of morality.” 248, 2 Does the feeling which accompanies the idea of justice come from nature or could it have grown up out of the idea itself? 248, 3 The sentiment does not arise from an idea of expediency. 248, 4 “[T]he two essential ingredients in the sentiment of justice” is the desire for vengeance and the knowledge that there is some specific victim of injustice. 248, 5 The desire to punish comes from the impulse of self-defense and the feeling of sympathy. Outline of J.S. Mill’s Utilitarianism 7 248, 6 It is natural for us to resent harm and retaliate in response to it. We differ from animals a) in extending this response to all other humans and b) through our greater intelligence extending the notion of community of interest to society as a whole. 248, 7—249, 1 The desire for vengeance is moral when it serves the common good. 249, 2 Resentment becomes moral when it is turned into “a rule which all rational beings might adopt with benefit to their collective interest.” He specifically cites Kant in support of this view. 249, 3—250, 1 “To recapitulate: the idea of justice supposes two things: a rule of conduct, and a sentiment which sanctions the rule. The first must be supposed common to all mankind, and intended for their good. The other (the sentiment) is a desire that punishment may be suffered by those who infringe the rule….And the sentiment of justice appears to me to be, the animal desire to repel or retaliate a hurt or damage to oneself, or to those with whom one sympathizes, widened so as to include all persons, by the human capacity of enlarged sympathy, and the human conception of intelligent selfinterest. From the latter elements, the feeling derives its morality; from the former, its peculiar impressiveness, and energy of self-assertion.” 250, 2 Definition of a ‘right’: “a valid claim on society to protect [a person] in the possession of it.” 250, 3—251, 1 The utility of justice is based on our fundamental need for security. On security our whole lives depend. 251, 2 What other basis for justice can be found? 251, 3—252, 1 Don’t say the concept of utility is uncertain compared with justice; there’s as much controversy about the one as the other. 252, 2—253, 1 Give examples of the controversy about justice in the many disagreements about the legitimacy of inflicting punishment. 253, 2 used. Then there’s all the disagreement about what standard of punishment should be 253, 3—254, 1 Then there are all the questions regarding social and economic justice in the distribution of society’s goods: should society focus on merit or on need? 254, 2—255, 1 Similar disputes arise regarding taxation. 255, 2 Nevertheless, justice is not identical with expediency. It is based on “the essentials of human well-being,” regarding which we all have rights. Outline of J.S. Mill’s Utilitarianism 8 255, 3—256, 1 The moral rules against hurting one another are the most vital ones to us, and thus the most useful. He gives a general list of them (256, 1). 256, 2 Not only is returning evil for evil intimately connected with our idea of justice, but of rewarding good with good. Breach of friendship or breach of promise is similarly essential to our idea of justice and also helps place justice above expediency. 257, 1 The currently prevailing rules of justice reflect the principles we have stated. 257, 2—259, 1 Such judicial virtues are impartiality and equality of treatment. Equality must prevail “except when some recognized social expediency requires the reverse.” (258,1) “The entire history of social improvement” has tended to erase distinctions between “slaves and freemen, nobles and serfs, patricians and plebeians; and so it will be, and in part already is, with the aristocracies of colour, race, and sex.” (259, 1) 259, 2 “[J]ustice is a name for certain moral requirements, which, regarded collectively, stand higher in the scale of social utility, and are therefore of more paramount obligation, than any others; though particular cases may occur in which some other social duty is so important, as to overrule any one of the general maxims of justice.” 259, 3 These considerations “resolve…the only real difficulty in the utilitarian theory of morals.” Justice is equivalent to expediency; we simply have to remove the conflicting sentiments that attach to these two terms. When we do that, justice “no longer presents itself as a stumbling-block to the utilitarian ethics. Justice remains the appropriate name for certain social utilities which are vastly more important, and therefore more absolute and imperative, than any others are as a class…; and which, therefore…are…guarded by a sentiment…distinguished from the milder feeling which attaches to the mere idea of promoting human pleasure or convenience, at once by the more definite nature of its commands, and by the sterner character of its sanctions.” © Robert Greene, 2007 Philosophy 308 Spring 2007 UW-Eau Claire