Lecture 9

advertisement

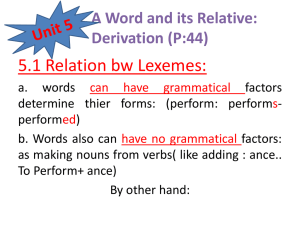

Lecture Nine: Semantics Part I By answering the question ‘what is semantics?’ we immediately raise another question. For, if semantics is the study of ‘meaning’, how do we define ‘meaning’? Before we can even begin to look at what semantics studies, we need to have a clearer understanding of what is meant by ‘meaning’; a lexeme which has yet to be defined fully by the very linguists who attempt to define everything else in the English lexicon! Nevertheless, let’s begin with some views on what ‘meaning’ could be. The ‘naming’ theory This theory goes back at least as far as Plato, who said that a word in a language is a ‘form’ and that ‘meaning’ is the object the form denotes. So, for example, ‘dog’ is a form which denotes the four-legged creature which barks. Unfortunately, how can ‘love’ or ‘beauty’ or ‘admiration’ denote meanings when the objects themselves are not physically anywhere? And what about ‘fairy’ or ‘elf’ or ‘goblin’ that do not even exist? Clearly this theory is unsuitable, and at best, limited in usefulness and scope. Concepts The theory of ‘concepts’ is a somewhat more advanced theory. It states that ‘words’ and ‘things’ are related by ‘concepts’ in the mind. It can be pictured in this way by means of the semiotic triangle (Odgen and Richards, 1923): Thought or reference (i.e. the concept) Symbol (i.e. the word) Referent (i.e. the thing) ---- = indicates no direct connection. However, this theory is not perfect either. What is the exact connection between a ‘symbol’ and ‘thought’? When we use words we rarely think of a concept at all; we simply speak. And there are some words which are almost impossible to conceptualise, like ‘the’. This theory, then, is also unsatisfactory. Context and Behaviourism In the middle of the 20th century yet another theory developed among the behaviourist school led by Firth. Now linguists focused on observation more than theorising when trying to understand meaning. Meaning came to be based on context. This enabled linguists to view ‘meaning’ from a more objective and scientific standpoint, looking at meaning in the context of language behaviour (situation, context, use…). They said that , “We shall know a word by the company it keeps” (From, ‘A Concise Course On Linguistics For Students of English’). When Bloomfield joined in the research, he developed the theory further saying that the meaning of a word depends on “the situation in which the speaker utters it, and the response which it calls forth in the hearer” (ibid.). Bloomfield’s own model (1933) is helpful here: S -------- r ………s -------- R S = a physical stimulus r = a linguistic response to the stimulus s = a linguistic stimulus R = a response E.g. ‘Jill is hungry. She sees an apple and gets Jack to fetch it for her by speaking to him.’ (Ibid.). However, this theory also has its drawbacks. In order to interpret the meaning of words in relation to physical events, more needs to be known about the speaker and hearer. Mentalism Yet another school of thought was developed by the Chomsky school in the 1960s. They held that the main function of language is for the purpose of communication of ideas and they assume moreover that data can be acquired by intuition. This stems from two beliefs: Looking on a range of data is better than being restrictive and most researchers agree anyway ‘intuitively’ regarding ‘which sentences are synonymous, which sentences are ambiguous, which sentences are ill-formed or absurd’ (ibid.). Their theory can be represented as a diagram like this: Intuition supplies data Validate theories Or Either Construct theories to support data Test theories Conclusions Semantics, then, despite all the confusion over ‘meaning’, can be said to be the ‘study of the communication of meaning through language’, to follow Chomsky’s line of reasoning. The more we understand what language items ‘mean’ and how they relate to a ‘referent’, the closer we can come to understanding the human mind itself. It is clearly no easy task, and will be an on-going process in the decades to come. Types of Meaning We have so far discussed what ‘meaning’ may generally mean, but not what specific forms it takes. Leech (1981)1 provides a useful framework for this purpose. He highlights seven kinds of meaning: Conceptual meaning: logical, cognitive, denotative. E.g. ‘flower’ (i.e. there is a direct physical referent). Associative meaning: what is communicated by virtue of what language refers to. E.g. ‘love’ (i.e. thoughts, ideas, experiences, emotions…). Social meaning: what is communicated of the social circumstances of language use. E.g. ‘You’re a monkey!’ cf. ‘¡Eres mono!’ [Spanish] (i.e. ‘monkey’ gives an English-speaker the feeling of someone ‘cheeky’ in a childlike way, Refer to the textbook ‘A Concise Course On Linguistics For Students of English’ Ch5.3.1 to get a further set of examples and a breakdown of ‘sense’ and ‘meaning’. 1 whereas ‘mono’ gives a Spanish-speaker the feeling of someone ‘good looking’ in a colloquial way). Affective meaning: what is communicated of the feelings and attitudes of the speaker/writer. E.g. ‘I really hate Monday mornings!’ (i.e. a sense of ‘bad mood’ or ‘disgruntlement’). Reflected meaning: what is communicated through association with another sense of the same expression, i.e. puns and connotations. Collocative meaning: what is communicated through association with words that tend to occur in the environment of another word. E.g. ‘pride’ + ‘prejudice’ or + ‘fall’ [as in ‘pride comes before a fall’] (i.e. something negative), ‘sea’ + ‘sand’ (i.e. holidays, a pleasant experience). Thematic meaning: what is communicated by the way in which the message is organised in terms of order and emphasis. E.g. ‘On looking up from behind his newspaper, and while still pondering the grim tone of the article he had been reading before he was suddenly broken off by a loud dull thud, he spotted what he thought to be the lifeless form of a feline creature at the bottom of the stairs to his right, just behind the lamp in the corner…’ (i.e. suspense, a sense of foreboding). Now, let’s look at some specific details of interest to the semanticist. Synonymy ‘Synonymy’ really means ‘the state of possessing identical meaning’, so two words that are synonymous must be fully interchangeable in all situations clearly this is almost (if not) impossible. Fox defines synonymy as ‘sameness of meaning’, but this is also an absolute definition that does not work well in practice. The problem with many so-called synonyms is the fundamental attributes most words have, namely ‘denotation’ and ‘connotation’. Denotation means fundamental, or basic meaning: e.g. ‘man’ and ‘chap’ share the same denotation, because both refer to an adult male person. Connotation implies extra sociolinguistic meaning of a word: e.g. ‘man’ is a generic lexeme for any adult male person, but ‘chap’ has the added possible implication of ‘youth’, ‘regional dialect’ and may be considered ‘humorous’ in certain contexts. So, between ‘man’ and ‘chap’ there exists the same denotation but different connotations. Thus the two words cannot be classed as absolute synonyms. Similarly, two lexemes may mean exactly the same under certain equal conditions, but in other contexts only one of the lexemes is acceptable. For example, ‘range’ and ‘selection’ are synonymous in the sentence ‘what a nice _____ of furnishings’, but in the sentence ‘what a nice mountain _____’ only ‘range’ is possible. Sets of lexemes like ‘range’ and ‘selection’ are called collocationally-restricted synonyms. There are other types of synonymy, also, as follows. 1. Dialectal synonyms are many in English due to the large number of independent English-speaking communities throughout the world. For example, in Standard American English you would say hood, pavement, sidewalk, diaper, fall, which correspond with bonnet, road surface, footpath, nappy, autumn in Standard English English. 2. Stylistic differences are found in many ‘synonymous pairs’. Compare ‘one should’ and ‘you should’, ‘football’ and ‘footy’, and ‘insane’ and ‘nuts’, for example. 3. Differences according to register happen especially in the development of scientific, legal and academic English. Indeed of any specialist field. Here the difference is between a ‘technical term’ applied to something and the ‘popular term’ that non-specialists would employ. For example, a chemist would say ‘sodium nitrate’ but everyone else would say ‘salt’. Zoologists would talk about ‘bovine mammals’ when everyone else would say ‘cows’. 4. Near synonyms are often found in dictionaries and thesauruses in the form of lists of words with similar meanings (i.e. sharing the same denotation), but only mean exactly the same thing as another lexeme of the same set under certain circumstances. E.g. ‘pleasant’ can have the meaning of ‘nice’, ‘kind’, ‘good’, ‘friendly’, ‘likeable’ and ‘fine’ as in these example sentences: It’s nice/pleasant weather. He’s a kind/pleasant man. It’s a good/pleasant day. It’s a friendly/pleasant place. He’s a likeable/pleasant chap. It’s a fine/pleasant summer. But you could not say pleasant in this sentence: ‘It’s a fine/*pleasant dish’. Here only ‘fine’ has the meaning of ‘(the food) tastes very good’. Polysemy ‘Polysemy’ describes a lexeme that has more than one meaning. For example, the lexeme ‘set’ in ‘The Concise English Dictionary’ (1994) is listed as having 16 transitive verb meanings, 9 intransitive verb meanings, 6 adjectival meanings and 17 meanings as a noun! All those in only a concise dictionary! There are even more if you consult the OED! Homonymy These synonyms can be homophones, having the same pronunciation but different orthographic representation, as in great-grate, red-read, so-sew, toetow, threw-through and two-to-too. Incidentally, homophones make great jokes: ‘What is black and white and /red/ all over?’ Answer: ‘A newspaper.’ (/red/ = ‘red’ and ‘read’). They can also be homographs, having the same orthographic representation but different pronunciation, as in wind-wind and tear-tear. Hyponymy This describes the paradigmatic relationship between two lexemes. ‘Paradigmatic’ means that a specific lexeme is subordinate (= hyponymous) to a more general lexeme which is, in turn, superordinate to it: For example, ANIMATE PLANT ANIMAL HUMAN ANIMAL MALE FEMALE COW DOG BULL COW CALF In the above example ‘bull’ is hyponymous (or subordinate) to ‘cow’ which is again subordinate to ‘animal’. The higher up the paradigm you move, the more general the term becomes. As you move down the paradigm the lexemes become ever more specific variants of the more general term above. Also, lexemes which belong to the same superordinate lexeme (like ‘animal’ and ‘plant’ [both belong to ‘animate’], or ‘bull’, ‘cow’ and ‘calf’ [all belong to ‘cow’]) are called co-hyponyms, because they are all immediately subordinate to the same lexeme. Antonymy This is just as confusing as ‘synonymy’. It is often taken to mean ‘oppositeness of meaning’, but there are no words which could usually be called true opposites, for the same reasons that there can be no really true synonyms. However, we can talk of various degrees of antonymy. 1. Gradable opposites are opposites of degree and can be preceeded by ‘very + _____’ or ‘quite + _____’. For example, tall/short, old/young, fat/thin, near/far, dark/light, good/evil, hungry/full and dry/wet. 2. Complementary (non-gradable) opposites are terms which complement each other. The test is: ‘If A is not x then it’s y. If A is y, then it’s not x’. For example, single/married, man/woman, boy/girl and grandmother/grandfather. 3. Relational (converse) opposites express the reversal of a relationship between two things. The test is: ‘x presupposes y and y presupposes x’. For example, sun/moon, day/night, buy/sell, give/take, eat/drink, temporal/permanent, here/there, dress/undress, come/go, love/hate.