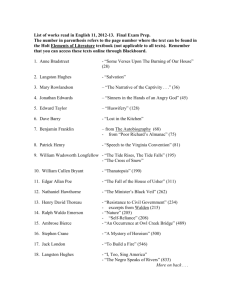

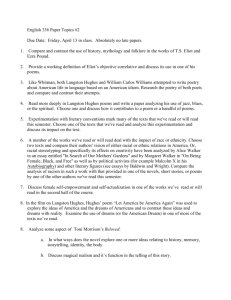

Mother to Son – Langston Hughes (Bio, Historical Context, and

advertisement

“Mother to Son” Mother to Son – Langston Hughes (Poet’s Life) “Mother to Son” was first published in the magazine Crisis in December of 1922 and reappeared in Langston Hughes’s first collection of poetry, The Weary Blues in 1926. In that volume and later works, Hughes explores the lives of African-Americans who struggle against poverty and discrimination. Hughes was dubbed “the poet laureate of Harlem” for his many portraits of Harlem as a crossroads of African-American experience. “Mother to Son” is a dramatic monologue, spoken by the persona of a black mother to her son. Using the metaphor of a stairway, the mother tells her son that the journey of life more closely resembles a long, trying walk up the dark, decrepit stairways of a tenement than a glide down a “crystal stair.” The “crystal stair” is a metaphor for the American dream and its promise that all Americans shall have equal opportunities. The mother warns her son not to expect an easy climb or a tangible reward. Through the metaphor of ascent, however, the speaker suggests that her endurance and struggle are necessary to progress toward racial justice and to maintain spiritual hope and faith. In this poem, Hughes represents the personal, collective, and spiritual importance of struggle, endurance, and faith. Author Biography Hughes was born in in 1902 in Joplin, Missouri, to James Nathaniel and Carrie Mercer Langston Hughes, who separated shortly after their son’s birth. Hughes’s mother had attended college, while his father, who wanted to become a lawyer, took correspondence courses in law. Denied a chance to take the Oklahoma bar exam, Hughes’s father went first to Missouri and then, still unable to become a lawyer, left his wife and son to move first to Cuba and then to Mexico. In Mexico, he became a wealthy landowner and lawyer. Because of financial difficulties, Hughes’s mother moved frequently in search of steady work, often leaving him with her parents. His grandmother Mary Leary Langston was the first black woman to attend Oberlin College. She inspired the boy to read books and value an education. When his grandmother died in 1910, Hughes lived with family friends and various relatives in Kansas. In 1915 he joined his mother and new stepfather in Lincoln, Illinois, where he attended grammar school. The following year, the family moved to Cleveland, Ohio. There he attended Central High School, excelling in both academics and sports. Hughes also wrote poetry and short fiction for the Belfry Owl, the high school literary magazine, and edited the school yearbook. In 1920 Hughes left to visit his father in Mexico, staying in that country for a year. Returning home in 1921, he attended Columbia University for a year before dropping out. For a time he worked as a cabin boy on a merchant ship, visited Africa, and wrote poems for a number of American magazines. In 1923 and 1924 Hughes lived in Paris. He returned to the United States in 1925 and resettled with his mother and half-brother in Washington, D.C. He continued writing poetry while working menial jobs. In May and August of 1925 Hughes’s verse earned him literary prizes from both Opportunity and Crisis magazines. In December Hughes, then a busboy at a Washington, D.C, hotel, attracted the attention of poet Vachel Lindsay by placing three of his poems on Lindsay’s dinner table. Later that evening Lindsay read Hughes’s poems to an audience and announced his discovery of a “Negro busboy poet.” The next day reporters and photographers eagerly greeted Hughes at work to hear more of his compositions. He published his first collection of poetry, The Weary Blues, in 1926. Around this time Hughes became active in the Harlem Renaissance, a flowering of creativity among a group of African-American artists and writers. Hughes, Zora Neale Hurston, and other writers founded Fire!, a literary journal devoted to African-American culture. The venture was unsuccessful, however, and ironically a fire eventually destroyed the editorial offices. In 1932 Hughes traveled with other black writers to the Soviet Union on an ill-fated film project. His infatuation with Soviet Communism and Joseph Stalin led Hughes to write on politics throughout the 1930s. He also became involved in drama, founding several theaters. In 1938 he founded the Suitcase Theater in Harlem, in 1939 the Negro Art Theater in Los Angeles, and in 1941 the Skyloft Players in Chicago. In 1943 Hughes received an honorary Doctor of Letters from Lincoln University, and in 1946 he was elected to the National Institute of Arts and Letters. He continued to write poetry throughout the rest of his life, and by the 1960s he was known as the “Dean of Negro Writers.” Hughes died in New York on May 22, 1967. Source Citation: "Mother to Son." Poetry for Students. Ed. Marie Rose Napierkowski and Mary Ruby. Vol. 3. Detroit: Gale, 1998. 177-189. Gale Virtual Reference Library. Web. 25 Feb. 2013. Mother to Son – Langston Hughes (Historical Events) Historical Context By 1926, when Hughes published this poem in his book The Weary Blues, the artistic movement that we know as the Harlem Renaissance was at the height of its fame and productivity. The Harlem Renaissance, an informal gathering of writers, painters, musicians, and philosophers who worked in the Harlem section of New York City in the 1920s, started soon after World War I ended in 1918 and withered away by the time the Great Depression began with the stock market crash of 1929. To some extent, we can say that it is a happy coincidence that some of the world’s greatest talents all ended up in the same place at the same time. Looking more deeply, though, we see that the outpouring of expression during the Harlem Renaissance was driven not just by talent but by an urgent need to express a cultural identity. Harlem in the 1920s was the place where the artistic sensibilities of black America were inevitably destined to attract the attention of the world. In the nineteenth century the majority of African Americans lived in the South because they were descendants of slaves who had been brought here to farm the massive plantations in that region. After the Confederate Army of the South surrendered in 1865, bringing an end to the Civil War, slavery was abolished in this country. The Southern legislatures, however, passed laws that made it impossible for blacks to become socially or economically equal to whites. These “Jim Crow laws” (named after an offensively stupid and lazy black character from a 1832 minstrel show) blocked voting or land ownership by blacks by holding them to nearly impossible “intelligence tests” or “economic criteria” that most whites would have also failed to meet if they had been required. In 1896 the U.S. Supreme Court gave its approval to these discriminatory laws by deciding in the case of Plessy v. Ferguson that states could offer “separate but equal” facilities to blacks for education, transportation, and public accommodations. The pretense toward fairness in this ruling ignored the fact that the accommodations were almost never equal: less government money found its way to black hospitals, bus lines, parks, etc., and private enterprises certainly offered blacks only their worst. It was not until 1954 that the Supreme Court ruled the “separate but equal” doctrine unfair, in a case called Brown v. The Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas. Early in the twentieth century, though, Southern blacks found some form of relief from the unequal conditions with the Industrial Revolution and the growth of major manufacturing centers in Northern cities such as Chicago, Detroit, Pittsburgh, Cleveland, and New York. There was still terrible discrimination in the North, but it was not formally established in the laws. In addition, the factories of the North, producing steel and automobiles, needed laborers, and they paid good wages to workers with no prior experience. When World War I began in Europe in 1914, the push to provide munitions made the North even more inviting to African Americans. A laborer making $1.10 per day in the South could make $3.75 in a Northern factory, while a woman working as a domestic in the South for $2.50 per week could make $2.10 to $2.50 a day in the North. The war also opened manufacturing opportunities for blacks by narrowing the number of immigrant workers coming from Europe. The black population in Northern cities ballooned; in New York City alone, the number of blacks went from 60,666 in 1900 to 152,467 in 1920, growing throughout the twenties to 327,706 by 1930. The urban African Americans began to seek their own identity in ways that they never had a chance to when they were dispersed on farms throughout the South. During the war, approximately 367,000 blacks served in the Armed Forces. Although still facing considerable discrimination in the military, black servicemen brought home a new awareness of how small and temporary many American prejudices were. Military service exposed many white Americans to blacks for the first time, and they learned respect. The characteristics that racists had claimed about in blacks in order to oppress them for decades—claiming that they were simple, naive, ignorant and primitivistic—ironically started looking good to intellectuals, in light of the sophisticated and rational war that had just taken so many lives barbarically. After the war, the Harlem section of New York City, where blacks comprised over 90 percent of the population, became recognized as a center for artistic and intellectual activity. It offered blacks both the security of a small, self-contained community and, at the same time, as part of America’s publishing and entertainment capital, it offered access to national and international audiences. At night, New York’s wealthiest went “up to Harlem” in search of clubs that served liquor, which had been made illegal in 1920 by the Constitution’s Eighteenth Amendment. Rich intellectuals rubbed shoulders with poor intellectuals: Hughes himself was in fact “discovered by” prominent poet Vachel Lindsay when he slipped some poems to Lindsay while waiting on his table. Together, writers and artists of the Harlem Renaissance raised the world’s consciousness of what life was like for Americans of African descent. Source Citation: "Mother to Son." Poetry for Students. Ed. Marie Rose Napierkowski and Mary Ruby. Vol. 3. Detroit: Gale, 1998. 177-189. Gale Virtual Reference Library. Web. 25 Feb. 2013. Mother to Son – Langston Hughes (Criticism) Poem Summary Lines 1-2 The first two lines establish what the title implies: this poem is a dramatic monologue spoken by the persona of a mother to her son. The son never speaks; the mother’s life experience and advice may therefore apply to all readers, but particularly to young AfricanAmerican readers. The metaphor of the crystal stair may represent several things. It may symbolize dreams that the mother once held but which she has learned no longer to expect. The crystal stair may also represent the mother’s spiritual quest toward heaven, Christian grace, and redemption. Or, in material terms, it may invoke the large, gleaming staircases that starlets glide down in movies. In each possible interpretation, the crystal stair connotes smoothness and ease, delicacy, wealth, and a clear, well-lit path toward a rich (material or spiritual) destination. These connotations contrast with images in the poem that show how rough and discouraging the mother’s actual life has been. Lines 3-7 In these lines, the mother describes the specific ways that her life’s journey has diverged from the ideal of the crystal stair. Grammatically, the “it” in line 3 refers to the subject of the previous sentence: “Life.” Thus one might interpret the line to read, “my life’s had tacks in it.” Or, extending the metaphor of the stairway (of life), the “it” may refer to stairs. Tacks and splinters may be read as figurative hazards one might find on an actual stairway in a rundown building. The tacks, splinters, worn-out carpet, and torn-up boards represent overuse and neglect. Many travellers before the mother have hauled themselves on this journey, and many will do so after her. The damaged parts of the stairway may represent the inability of individual sojourners to repair the structures under-girding their lives (such as poverty and reduced opportunity) or it may represent the disadvantaged state of black life in America itself. The “torn up” boards may represent someone’s attempt to dismantle this stairway altogether. R. Baxter Miller interprets the “tacks” and “splinters” in this poem as threats to the mother’s body and soul. Physically, the tacks and splinters represent small, nagging pains that might puncture and infect the mother as she struggles upward. Symbolically, however, these small threats represent potential injuries to “the black American soul.” The mother’s recognition of these obstacles and her apparent avoidance of them signal her wise negotiation of life’s setbacks. Lines 8-11 Having listed some of the literal and figurative hazards the son might encounter on his journey, the mother affirms the value of persistence and faith in one’s goal. From lines 8 to 13, she makes it clear that, despite obstacles, she has continued to make gains. The mother’s personal advancement represents progress for the black race as well. The landings and turns in the mother’s climb may be metaphors for brief victories or respites from personal, racial, or spiritual struggles. The mother may mention these moments of ease to assure the son that some parts of life’s uphill climb will offer glimpses of hope and accomplishment. Lines 12-13 Like the tacks and splinters in lines 3 and 4, the image of a dark stairway with the light removed, broken, or never installed, calls to mind an actual stairway in a building of poor tenants. Hughes includes such realistic details to make the metaphor of a stairway literal and symbolic at once. It is easier for readers to grasp and remember ideas that they can picture or sense, so poets often include sensory details in their work. In this poem, Hughes carefully includes details that appeal to the reader’s vision, hearing, and touch. The tacks and splinters of lines 3-4 awaken the reader’s sense of touch and danger; the darkness in lines 12-13 causes the reader to experience the mother’s blind groping around obstacles toward an unseen goal. The mother’s “goin’ in the dark / Where there ain’t been no light” may represent her persistent struggles despite her own waning faith or hope. Or, the dark may symbolize the external obstacles despite which she climbs. Hughes may repeat the idea of darkness twice in lines 12-13 to suggest different kinds of darkness: physical and spiritual. Or the repetition may serve to make the mother’s words sound like real speech, which is usually more repetitive and colloquial than written words. Lines 14-20 From line 14 to 20, the mother’s advice takes a final turn. Whereas the first seven lines depict the hardships the son can expect in life and the next six lines assert the mother’s example of persistence through adversity, the final seven lines urge the son to keep going, despite setbacks and his wishes to stop or turn back. The critic Onwuchekwa Jemie translates the mother’s command in line 15, not to “set down on the steps,” into specifically black, urban, social terms. In Langston Hughes: An Introduction to the Poetry, Jemie argues that “to stop is to become a sitter on stoops and stander on street corners … or to become a prostitute, pimp, hustler or thief. To despair is, in short, to wither and die.” The mother urges the son not to succumb to the temptation to give up. Having felt despair and resisted it, she knows that the choice to persist benefits the individual and the race. She warns him in line 17 not to fall ‘now’ because she has brought them so far and is ‘still climbin’.” The potential “fall” might symbolize both their falls from spiritual grace as well as a political setback for African Americans. Collectively, if many sons (and daughters) despair and drop out, the struggle for equality is that much less likely to succeed. In the last line, the mother repeats her refrain regarding the moral, spiritual, and political necessity to endure adversity and keep climbing. Themes Race and Racism The struggle that the mother in this poem describes is common to all people of every race and class, but Hughes narrows in on her identity by giving the speaker’s voice the dialect of a poor, undereducated African American. Readers who recognize this dialect and who have even a little knowledge about the struggle for racial equality in the United States will be able to associate the “staircase” metaphor and the setbacks that the speaker says she faced with the obstacles faced by American blacks, particularly in the early twentieth century, when the laws of the land permitted discriminatory practices. Particular clues that this is a southern black dialect include the contraction of “I is” (“I’se) meaning a mixture of “I am” and “I have”; the addition of the prefix “a-” to the word “climbin’” to indicate that the action is still going on; and the term of endearment “honey.” Independently, none of these stylistic traits would be enough to identify the speaker’s culture, but Hughes does such a thorough job of weaving a pattern together, that even a reader who is unfamiliar with the author’s racial background would get a sense of who the poem’s speaker is. The difficulties faced by the mother in this poem are symbolized by tacks, splinters, bare floors, and dark hallways—all signs of poverty. In associating this particular black American speaker with these particular images, Hughes is able to hint at the injustice in the relationship between poverty and race. This mother certainly is not poor because she is lazy or weak-willed, since we can see her determination to work and succeed in almost every line. For a woman of such determination to be kept this poor indicates that hardship is not a moral issue, but is related to an external cause, such as the limits that are put on people because of their race. Style Since “Mother to Son” is a dramatic monologue, the primary purpose of Hughes’s word choices and line arrangements is to quickly and convincingly capture the speech and character of a disadvantaged African-American mother. To more closely approximate the rhythms and folk diction, or word choices, of a black persona or character, Hughes uses a number of poetic and literary techniques. He writes in free verse, meaning the lines are un-rhymed and vary in length and meter (the pattern of beats in each line). Specifically, the number of syllables per line varies from one (line 7 is “Bare.”) to ten (in line 20, which iambic pentameter). In addition to capturing the rhythms of ordinary speech, the poem’s irregular line lengths may mirror the setbacks, turns, and uneven progress of the speaker on her life’s climb. Sometimes, a poem’s shape on the page reinforces its themes. Hughes uses other markers of African-American speech, such as contractions and colloquial uses of the verb “to be”: “I’se been aclimbin’ on” and such variations as “set” for “sit”: “Don’t you set down.” Hughes sought to represent African-American speech with dignity and verve for, in the hands of many white American writers, black dialect was used to perpetuate stereotypes of black ignorance. Hughes sought to overturn such caricatures by representing humor, strength, wisdom, and music in the plain speech of his African-American poetic personas. After carefully interpreting the mother’s insights and messages to her son, the reader recognizes that in “Mother to Son” and many of Hughes’s poems, uneducated diction signifies a lifetime of reduced opportunity rather than ignorance or lazy speech. Thus, the emotional drama of the mother’s will to persist is heightened considerably by the disadvantage that her diction bespeaks. Critical Overview Commentators on “Mother to Son” tend to focus on either racial, religious, or feminist themes for the poem’s forms. Chidi Ikonne, writing in the collection Langston Hughes, suggests that this and other poems by Hughes present a stance of “stability which, ironically, has developed from the instability of the speaker’s experience” in a racist society. Emphasizing religious themes, R. Baxter Miller, in his 1989 book The Art and Imagination of Langston Hughes, argues that the mother in this poem is a “figure of mythic ascent” who is struggling to “merge with Godhead.” Miller argues that “we find in her less a progression of the body than an evolution of the soul.” With a similar emphasis on religious symbolism, Onwuchekwa Jemie refers to the mother as a “Black Madonna” in his book Langston Hughes: An Introduction to the Poetry. Other critics illuminate the poem’s feminist elements. Critic James Emanuel, in his 1967 book Langston Hughes, notes that “Mother to Son” is among the first of many of Hughes’s poems to portray a strong matriarch. R. Baxter Miller also discusses the symbolic role of women and mothers in Hughes’s poetry. Miller argues that Hughes’s female speakers represent archetypes, or original models, of human “endurance, … mortality, [and] marital desertion.” In this poem, the woman also represents the continuation of the race. Having given life to the next generation (her son), raised him, and persisted in her struggles for his sake and that of future generations, the mother represents a figure of female strength, affirmation, and generational continuity. Still other critics focus on the poem’s lyric elements. James Baldwin, a major African-American writer contemporary with Hughes, commented that “Hughes is at his best … in lyrics like ‘Mother to Son’ and ‘The Negro Speaks of Rivers’.” The poem’s lyric elements include a first person speaker, an expression of intense personal emotion, and a belief in spiritual transcendence of time and earthly circumstance. Source Citation: "Mother to Son." Poetry for Students. Ed. Marie Rose Napierkowski and Mary Ruby. Vol. 3. Detroit: Gale, 1998. 177-189. Gale Virtual Reference Library. Web. 25 Feb. 2013.