BOUYGUES (UK) LTD v DAHL

advertisement

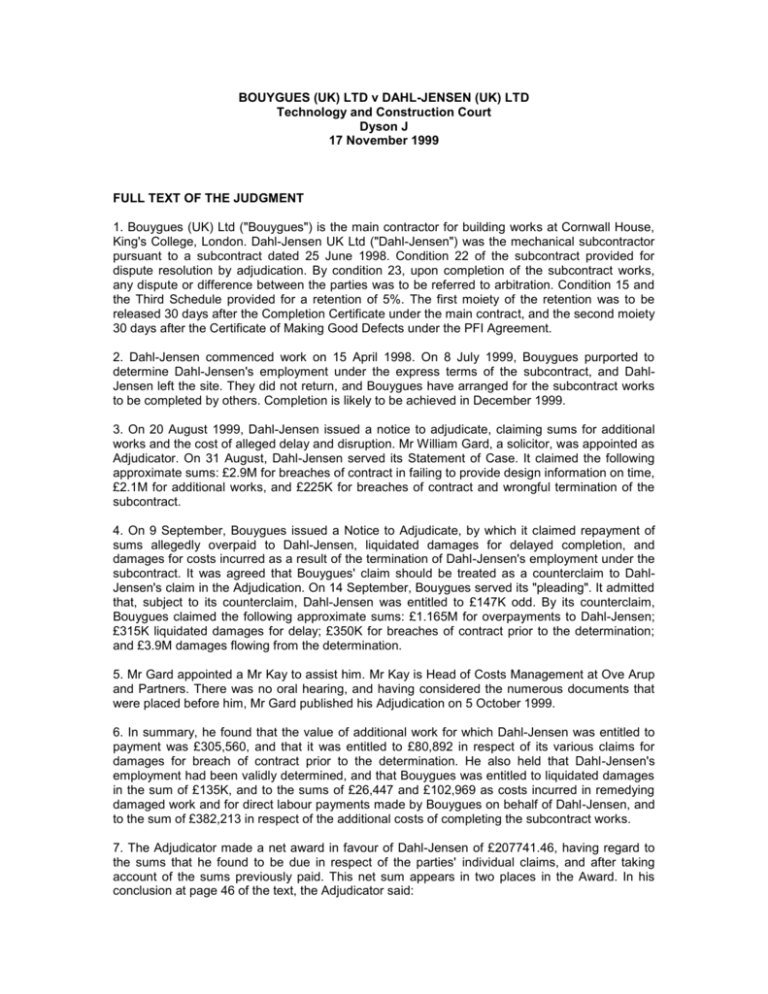

BOUYGUES (UK) LTD v DAHL-JENSEN (UK) LTD Technology and Construction Court Dyson J 17 November 1999 FULL TEXT OF THE JUDGMENT 1. Bouygues (UK) Ltd ("Bouygues") is the main contractor for building works at Cornwall House, King's College, London. Dahl-Jensen UK Ltd ("Dahl-Jensen") was the mechanical subcontractor pursuant to a subcontract dated 25 June 1998. Condition 22 of the subcontract provided for dispute resolution by adjudication. By condition 23, upon completion of the subcontract works, any dispute or difference between the parties was to be referred to arbitration. Condition 15 and the Third Schedule provided for a retention of 5%. The first moiety of the retention was to be released 30 days after the Completion Certificate under the main contract, and the second moiety 30 days after the Certificate of Making Good Defects under the PFI Agreement. 2. Dahl-Jensen commenced work on 15 April 1998. On 8 July 1999, Bouygues purported to determine Dahl-Jensen's employment under the express terms of the subcontract, and DahlJensen left the site. They did not return, and Bouygues have arranged for the subcontract works to be completed by others. Completion is likely to be achieved in December 1999. 3. On 20 August 1999, Dahl-Jensen issued a notice to adjudicate, claiming sums for additional works and the cost of alleged delay and disruption. Mr William Gard, a solicitor, was appointed as Adjudicator. On 31 August, Dahl-Jensen served its Statement of Case. It claimed the following approximate sums: £2.9M for breaches of contract in failing to provide design information on time, £2.1M for additional works, and £225K for breaches of contract and wrongful termination of the subcontract. 4. On 9 September, Bouygues issued a Notice to Adjudicate, by which it claimed repayment of sums allegedly overpaid to Dahl-Jensen, liquidated damages for delayed completion, and damages for costs incurred as a result of the termination of Dahl-Jensen's employment under the subcontract. It was agreed that Bouygues' claim should be treated as a counterclaim to DahlJensen's claim in the Adjudication. On 14 September, Bouygues served its "pleading". It admitted that, subject to its counterclaim, Dahl-Jensen was entitled to £147K odd. By its counterclaim, Bouygues claimed the following approximate sums: £1.165M for overpayments to Dahl-Jensen; £315K liquidated damages for delay; £350K for breaches of contract prior to the determination; and £3.9M damages flowing from the determination. 5. Mr Gard appointed a Mr Kay to assist him. Mr Kay is Head of Costs Management at Ove Arup and Partners. There was no oral hearing, and having considered the numerous documents that were placed before him, Mr Gard published his Adjudication on 5 October 1999. 6. In summary, he found that the value of additional work for which Dahl-Jensen was entitled to payment was £305,560, and that it was entitled to £80,892 in respect of its various claims for damages for breach of contract prior to the determination. He also held that Dahl-Jensen's employment had been validly determined, and that Bouygues was entitled to liquidated damages in the sum of £135K, and to the sums of £26,447 and £102,969 as costs incurred in remedying damaged work and for direct labour payments made by Bouygues on behalf of Dahl-Jensen, and to the sum of £382,213 in respect of the additional costs of completing the subcontract works. 7. The Adjudicator made a net award in favour of Dahl-Jensen of £207741.46, having regard to the sums that he found to be due in respect of the parties' individual claims, and after taking account of the sums previously paid. This net sum appears in two places in the Award. In his conclusion at page 46 of the text, the Adjudicator said: "17 Conclusion: I conclude that: 17.1 The Claimant is entitled to the following in respect of its CVIs/Variations Claim: £305,560-77 17.2 The Claimant is entitled to the following in respect of its Damages Claim: £80,982-20 17.3 The Respondent is entitled to the following in respect of its Counterclaim: £178,801-51 17.4 The net result is that the Claimant is entitled to the sum of: £207,741-46" 8. In Schedule 5 to his decision he set out a "Summary Assessment for both Claim and Counterclaim". To the original tender sum of £5,450,000 he added various items to produce a total of £7,626,542.97. From this, he deducted sums due to Bouygues to arrive at a figure of £6,979,912.52. This was a gross figure in the sense that it included the 5% retention. He then deducted the total of interim payments to date (£6,732,171.06) to arrive at £207,741.46. The interim payments excluded the 5% retention. 9. The sum of £178,801.51, which appears in the conclusion of the text derives from Schedule 5 to the Award, which is a "Counterclaim Analysis". Here, the Adjudicator carried out a similar exercise starting with the original tender sum, adding various items, deducting the sums due to Bouygues as well as the total of interim payments, this time arriving at an overpayment of £178,801.51. Once again, there was a deduction of a sum which excluded the 5% retention from a sum which included it. 10. As for costs, in accordance with paragraph 28 of the CIC Procedure, he directed that the parties should bear their own costs. As for his own fees and expenses, he directed that these be borne "on the basis of the usual principles of English law". The problem 11. The problem which is central to the issues that I have to decide is this. In arriving at the figure of £178,801.51 in Schedule 5 (which is carried through to the net sum of £207,741.46 in the conclusion), and in arriving at the sum of £227,741.46 in the Summary Assessment of Claim and Counterclaim, the Adjudicator took a gross sum which included the 5% retention, and deducted from it the sums that had been paid during the subcontract which excluded the retention. The effect of this was to release the retention to Dahl-Jensen at a time when there was not yet an entitlement to it under condition 15 of the subcontract. If the 5% retention had been deducted from the gross sum to which Dahl-Jensen was found to be entitled, that sum would have been reduced by £348,885.63 from £6,979,912 to £6,630,916. The overall effect would have been that there would have been a net award of £141,254 in favour of Bouygues, instead of a net award of £207,741 in favour of Dahl-Jensen. It is submitted by Mr Furst QC on behalf Bouygues that the Adjudicator's decision in effect to award the retention money to Dahl-Jensen was outside his jurisdiction, and is therefore not binding on the parties. The fundamental issue that I have to decide is whether this submission is correct. Other issues have been raised, but that is the key question. Subsequent correspondence 12. Upon receipt of the Adjudication decision, Messrs Masons, Bouygues' solicitors, wrote to Mr Gard on 7 October pointing out what they thought to be an "arithmetical error" resulting from the way in which the retention had been dealt with. They invited him to correct the "slip" and direct Dahl-Jensen to pay Bouygues £141,254.17. 13. By letter dated 8 October, Hammond Suddards, Dahl-Jensen's solicitors wrote to Mr Gard saying that he had no jurisdiction to revisit his award. They said that the Adjudicator was not bound by the retention provision in the contract, and that he was free to make such orders as he saw fit. Further, the error was not suitable for correction under the slip rule. 14. Mr Gard replied by letter dated 13 October. He wrote: " .... I reserved the right to rectify any "slip" in my Decision as if it were an Award published pursuant to the Arbitration Act 1996. I did this in view of the complex and detailed nature of the issues and the time which I had to consider them and publish a Decision. The relevant part of Section 57 of the Act states that the tribunal may, on its own initiative or on the application of a party: "(a) correct an Award so as to remove any clerical mistake or error arising from an accidental slip or omission or clarify or remove any ambiguity in the Award..." I have discussed the Respondent's point with Mr Kay and considered the submissions made on behalf of both Parties. I am clear that the calculations to which I have been referred by the Respondent (namely the summary in Schedule 5) correctly reflect my intention and do not contain a clerical mistake or error arising from an accidental slip or omission. I shall not therefore be making any amendment to my Decision. I am now functus officio as regards the Decision. In view of this, I am not in a position to give further reasons or deal with any further submissions on this issue, although I should be happy to do so with the Parties' agreement." 15. The parties did not ask Mr Gard to give further reasons. The Adjudication Scheme 16. It is common ground that the subcontract required any adjudication to be conducted in accordance with the Rules of the CIC Model Adjudication Procedure (second edition), which provides so far as material: "1. The object of adjudication is to reach a fair, rapid and inexpensive decision upon a dispute arising under the Contract and this procedure shall be interpreted accordingly. 4. The Adjudicator's decision shall be binding until the dispute is finally determined by legal proceedings, by arbitration (if the contract provides for arbitration or the parties otherwise agree to arbitration) or by agreement. 5. The parties shall implement the Adjudicator's decision without delay whether or not the dispute is to be referred to legal proceedings or arbitration. 8. Either Party may give notice at any time of its intention to refer a dispute arising under the Contract to adjudication by giving a written Notice to the other Party. The Notice shall include a brief statement of the issue or issues which it is desired to refer and the redress sought. The referring Party shall send a copy of the Notice to any adjudicator named in the Contract. 14. The referring Party shall send to the Adjudicator within 7 days of the giving of the Notice (or as soon thereafter as the Adjudicator is appointed) and at the same time copy to the other Party, a statement of its case including a copy of the Notice, the Contract, details of the circumstances giving rise to the dispute, the reasons why it is entitled to the redress sought, and the evidence upon which it relies. The statement of case shall be confined to the issues raised in the Notice. . 20. The Adjudicator shall decide the matters set out in the Notice, together with any other matters which the Parties and the Adjudicator agree shall be within the scope of the adjudication." The applications before me 17. There are three applications before me: Bouygues' claim under Part 8 of the Civil Procedure Rules for declarations as to and/or remission of the Adjudicator's decision. The declarations sought are that (a) in so far as the Adjudicator decided that £348,885.63 was payable to Dahl-Jensen, the award is void and should be set aside; (b) the sum of £141,254.17 is due from Dahl-Jensen to Bouygues; (c) the Adjudicator's award as to costs is void and should be set aside; and (d) the award should be remitted to the Adjudicator with a direction to make further awards as to the sum due from Dahl-Jensen to Bouygues and as to costs. Dahl-Jensen's application under Part 24 of the CPR for summary judgment in respect of the sum awarded by the Adjudicator by his decision. Dahl-Jensen's application to stay Bouygues' claim for declaratory relief and remission pursuant to section 9 of the Arbitration Act 1996. 18. It will be convenient to start with Dahl-Jensen's application for summary judgment, since if that succeeds, the remaining applications fall away. Claim for summary judgment 19. There is considerable common ground as to the approach that I should follow. Paragraph 20 of the CIC Model Adjudication Procedure defines the matters to be decided as "the matters set out in the Notice, together with any other matters which the Parties and the Adjudicator agree shall be within the scope of the adjudication". It is the Adjudicator's decision on these matters (and no other) which is binding on the parties (see paragraphs 4 and 5 of the Procedure). The Adjudicator's jurisdiction to decide disputes derives from the Model Procedure. To the extent that he purports to decide matters which do not fall within the scope of paragraph 20 and which therefore have not been referred to him, his decision does not come within paragraphs 4 and 5 and is void. 20. My attention has been drawn to Macob Civil Engineering Ltd v Morrison Construction Ltd [1999] BLR 93, 99, The Project Consultancy Group v Trustees of the Gray Trust [1999] 65 ConLR 146, and Palmers Ltd v ABB Power Construction Ltd [6 August 1999, unreported]. In the second of these cases, I held that a decision purportedly made under section 108(3) of the Housing Grants and Regeneration Act 1996 where there is no construction contract at all, or where the construction contract was entered into before Part II came into force is not a decision within the meaning of the subsection and is therefore not binding on the parties. 21. Also cited to me were two expert valuation cases. The first was Jones v Sherwood Computer Services PLC [1992] 1 WLR 277. In that case, an agreement to purchase shares contained a provision that if the parties and their accountants could not agree a statement of the amount of sales, the matter was to be referred to independent accountants to determine as experts, and their decision was to be binding and conclusive for all purposes. Independent accountants were appointed and made their decision. The plaintiffs started proceedings claiming a declaration that the firm had failed to take account of transactions which it ought to have taken into account. The Court of Appeal struck out the parts of the statement of claim that related to this claim. At page 287A, Dillon LJ said: "On principle, the first step must be to see what the parties have agreed to remit to the expert, this being, as Lord Denning M.R. said in Campbell v Edwards [1976] 1 WLR 403, 407G, a matter of contract. The next step must be to see what the nature of the mistake was, if there is evidence to show that. If the mistake made was that the expert departed from his instructions in a material respect - eg if he valued the wrong number of shares, or valued shares in the wrong company, or if as in Jones (M) v Jones (R.R.) [1971] 1 WLR 840, the expert had valued machinery himself whereas his instructions were to employ an expert valuer of his choice to do that - either party would be able to say that the certificate was not binding because the expert had not done what he was appointed to do. The present case is quite different, however, as Coopers have done precisely what they were asked to do." 22. This approach was applied by Knox J in Nikko Hotels (UK) Ltd v MEPC PLC [1991] 2 EGLR 103. That was a rent review case. The formula for increasing the rent required that the average hotel room rate be determined. The independent expert construed the expression "average room rate" as meaning the average of the published prices at which rooms were said to be available, rather than the average room rate actually achieved. The tenants issued an originating summons contending that the expert's decision was a nullity, since it was based on a misinterpretation of the rent review clause. The judge dismissed the summons holding that the expert's decision was conclusive and not open to review on the grounds that it was erroneous in law, unless it could be shown that the expert had not performed the task assigned to him: "if he has answered the right question in the wrong way, his decision will be binding. If he has answered the wrong question, his decision will be a nullity" (p 108B). 23. In my judgment, there is a reasonably close analogy between these expert valuation cases and adjudication cases. It is right to point out, however, that an enforceable decision of an expert is truly conclusive, whereas an enforceable decision of an adjudicator appointed under the CIC Model Procedure or the Scheme for Construction Contracts provided by Part II of the Housing Grants, Construction and Regeneration Act 1996 is only binding until the dispute is finally determined by litigation, arbitration or agreement. 24. The first step is to see what disputes were referred to Mr Gard. I have already summarised these. It is common ground that the disputes did not include a claim for the release of either moiety of the retention sum that was being withheld under the subcontract. 25. The second step is to see whether the Adjudicator made a mistake, and if so, how that mistake should be characterised. If the mistake was that he decided a dispute that was not referred to him, then his decision on that dispute was outside his jurisdiction, and of no effect. It is analogous to the valuer departing from his instructions in a material respect or answering the wrong question. But if the adjudicator decided a dispute that was referred to him, but his decision was mistaken, then it was and remains a valid and binding decision, even if the mistake was of fundamental importance. 26. I do not think that there is any dispute that this is the correct approach to be followed in the present case. The difference between the parties is as to the application of that approach to the facts of this case. Mr Furst submits that the fact that the effect of the decision was to award DahlJensen the whole of the retention shows that the Adjudicator decided a matter which was outside his jurisdiction, namely the question whether Dahl-Jensen was entitled to the release of the retention. 27. Mr Friedman QC does not concede that the Adjudicator made a mistake at all, but he has not put forward any justification of the decision, in effect, to order the release of the retention. In my judgment, the Adjudicator plainly made a mistake. Mr Friedman submits, however, that if there was a mistake, it was a mistake in the Adjudicator's calculations on the disputes that were referred to him, and not a mistaken decision to deal with or purport to deal with a dispute that was outside his jurisdiction. 28. In my view, Mr Friedman is right. There was no claim for the release of the retention. It is of some relevance to note, however, that there were some references to the question of retention in the "pleadings". Dahl-Jensen's statement of case included a claim for two months' loss of interest on the basis that delayed completion to the subcontract would lead to a delay in the release of the retention, whenever it was released. Bouygues' response was that the first moiety of the retention was not yet due, so that there could be no claim for interest. 29. Bouygues' counterclaim included a claim for the repayment of £1.165M allegedly overpaid. This sum was calculated by deducting from £7,050,796 (which comprised the aggregate of sums paid plus retention of £259,125) the sum of £5,885,506 (which was Bouygues' value of the work to date "excluding deduction of retention"). In its response, Dahl-Jensen contended that this claim was misconceived to the extent that it included the retention of £259,125, since no part of that sum had been released by Bouygues to Dahl-Jensen. In its further response, Bouygues asserted that the valuation of £5,885,506 included retention. 30. My reasons for preferring the submissions of Mr Friedman are as follows. First, Dahl-Jensen was not claiming the release of the retention. There was no express or even implied assertion in Dahl-Jensen's pleadings that it was entitled to the release of that money. On the contrary, both parties had stated in their pleadings that the retention was not yet due for release; Bouygues when answering the claim for two months' loss of interest, and Dahl-Jensen when dealing with the calculation of the amount of the alleged overpayment There were many issues between the parties, but it was common ground that Dahl-Jensen was not yet entitled to the release of the retention. The Adjudicator knew that the subcontract works had not been completed. In these circumstances, it would have been surprising if the Adjudicator had been of the view that one of the issues that had been referred to him was a claim for the release of the retention. 31. Secondly, the Adjudicator did not purport to determine that Dahl-Jensen was entitled to the release of the retention. It is significant that Mr Furst does not so contend. He submits rather that the effect of the decision was to award the retention money to Dahl-Jensen. 32. Thirdly, it is not difficult to make mistakes in doing complicated calculations, particularly when, as in these adjudication cases, the adjudicator is working under very severe time constraints. It seems to me that this is what has happened in this case. The seeds of the error are to be found in Bouygues' counterclaim, and in particular its claim for the repayment of money allegedly overpaid. It was this claim which made it necessary to calculate the sum to which Dahl-Jensen was entitled and compare it with the sum already paid. In performing this calculation, it was necessary to make sure that like was compared with like, and particularly to ensure that the retention percentage was deducted from both figures. As I have already said, it was common ground that the time for the release of the retention had not yet been reached. But it was easy enough to make a mistake and fail to deduct the retention from both figures. Indeed, Dahl-Jensen contended that Bouygues fell precisely into this error in calculating its claim for overpayment. Dahl-Jensen may not have been right about that, since the words "excluding deduction of retention" may well mean the same as "including retention". But what matters is that the point was not entirely clear: there was scope for possible confusion. 33. Fourthly, it is clear from the Adjudicator's conclusion at paragraph 17 of his award that the error that infected his decision derived from his miscalculation of the amount of the overpayment in the Counterclaim Analysis in Schedule 5. The word "retention" does not appear in that Analysis. It seems to me that the most natural interpretation of what happened is that the Adjudicator simply made a mistake in calculating the overpayment. There can be no doubt that what the Adjudicator was doing in his Counterclaim Analysis was calculating the amount of the overpayment. That was an issue that had been referred to him. To use the language of the expert valuation cases, he was doing precisely what he had been asked to do, and was answering the right question, but he was doing so in the wrong way. 34. I have reached this conclusion by looking at the "pleadings" and the decision itself. I do not consider that the issue whether the Adjudicator answered the right question in the wrong way or answered the wrong question can be resolved by an examination of the correspondence to which I have referred. It is true that he said that he did not make a "clerical mistake or slip", and that is no doubt why he refused to apply the slip rule. But in my view, even if it were appropriate to have regard to what the Adjudicator said about his decision after the event, his letter of 13 October does not shed light on the question whether he ruled on an issue that was not referred to him, or made a mistake in the way in which he decided an issue that was referred to him. 35. Mr Furst submits that, if Dahl-Jensen is permitted to enforce a decision which is plainly erroneous, Bouygues will suffer an injustice, and this will bring the adjudication scheme into disrepute. But as I said in Macob, the purpose of the scheme is to provide a speedy mechanism for settling disputes in construction contracts on a provisional interim basis, and requiring the decisions of adjudicators to be enforced pending final determination of disputes by arbitration, litigation or agreement, whether those decisions are wrong in point of law or fact. It is inherent in the scheme that injustices will occur, because from time to time, adjudicators will make mistakes. Sometimes those mistakes will be glaringly obvious and disastrous in their consequences for the losing party. The victims of mistakes will usually be able to recoup their losses by subsequent arbitration or litigation, and possibly even by a subsequent adjudication. Sometimes, they will not be able to do so, where, for example, there is intervening insolvency, either of the victim or of the fortunate beneficiary of the mistake. 36. Where the adjudicator has gone outside his terms of reference, the court will not enforce his purported decision. This is not because it is unjust to enforce such a decision. It is because such a decision is of no effect in law. In deciding whether a decision has been made outside an adjudicator's terms of reference, the court should give a fair, natural and sensible interpretation to the decision in the light of the disputes that are the subject of the reference. There will be some cases where it is clear that the adjudicator has decided an issue that was not referred to him or her. But in deciding whether the adjudicator has decided the wrong question rather than given a wrong answer to the right question, the court should bear in mind that the speedy nature of the adjudication process means that mistakes will inevitably occur, and, in my view, it should guard against characterising a mistaken answer to an issue that lies within the scope of the reference as an excess of jurisdiction. 37. In my judgment, therefore, Dahl-Jensen's claim for summary judgment succeeds. It follows that Bouygues' claim for declaratory relief and remission must be dismissed, and the application for a stay of that claim falls away.