Metaphysics: the Nature of Language

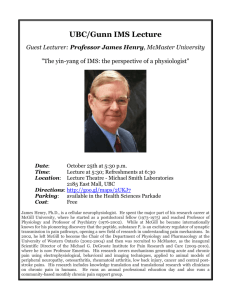

advertisement

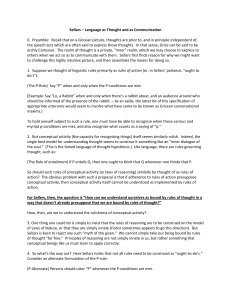

PHIL 421B Metaphysics: Topic for Winter 2006: The Nature of Language J. McGilvray 398-6053 james.mcgilvray@mcgill.ca Typical metaphysical questions (and the epistemological ones that accompany them) include: what are the natures of things? what is reality? which things are real? how do we gain access to things? does science yield a different set of things than those provided by common sense? how many things are there? are mental things different from physical things? and so on. In part because their natures are now so much discussed but also because they are so central to human nature and to human understanding and action, languages offer a particularly interesting case for raising and trying to answer these questions. The majority view among philosophers is that languages are socially constituted entities of a special sort – perhaps systems of communication, games, conventions, etc – somehow incorporating certain physical ‘vehicles’ (sounds, marks, shapes, perhaps even brain states…) that embody socially constituted functions for these vehicles so that they can serve the needs of communication, etc. Languages so conceived are somehow implanted in children by teaching and training, and the child who is taught a language expresses his or her language (and knowledge of language) in linguistic action and behavior that the community judges to be correct (or not) for the circumstances in which the behavior is expressed. An uncommon and relatively recent ‘biolinguistic’ challenge to this view suggests that languages are states of biophysical ‘organs’ in the human mind/brain, studied by the techniques of natural science. These organs do not develop their states through education or training; they are not taught. Rather, they grow into their final states (specific languages) in the way(s) other organic systems in the human body, such as the heart, grows into their final states – through some process of morphogensis, at least partially genetically controlled. Languages are biophysical entities. One prominent difference between languages as understood in these two ways is that the first thinks of languages as somehow outside the mind/brain, while the second holds that language and its elements (‘words’) are inside. There are many other differences. While we will read the work of several individuals, we focus on the works of two, Wilfrid Sellars and Noam Chomsky. Sellars calls himself a ‘scientific realist’; so one might expect him to adopt the biolinguitic view. In fact, his view is a paradigm of the majority one. Chomsky constructs and defends the novel biolinguistic view. Both explicitly raise and speak to the questions mentioned above. Both place their views of language in broader contexts; their views of language, mind, and other matters represent different philosophical and scientific traditions of the nature of the mind and how to go about studying it. Discussing their studies of language will allow us to think about the implications of ontological commitments for not just specialized ontological issues such as the mind/body problem, but for human behavior and action. Requirements: Midterm (in class), 30% Final paper (no longer than 10 pages) 70% Students are expected to participate actively in discussion. Books: Chomsky, Rules and Representations (new edition 2005, Columbia University Press).. Sellars, TBA This is a WebCT course. The detailed class schedule and reading assignments appear on the website. Some of the reading materials for this course will be available on the website. McGill University values academic integrity. Therefore, all students must understand the meaning and consequences of cheating, plagiarism and other academic offences under the Code of Student Conduct and Disciplinary Procedures (see www.mcgill.ca/integrity for more information).