historians arts

advertisement

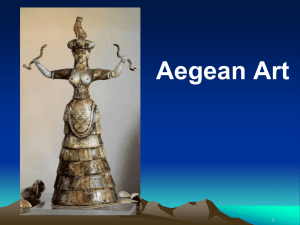

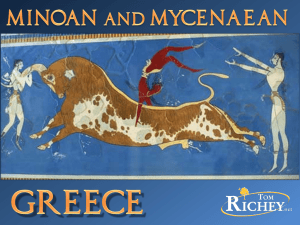

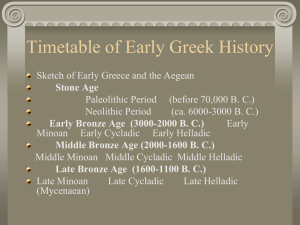

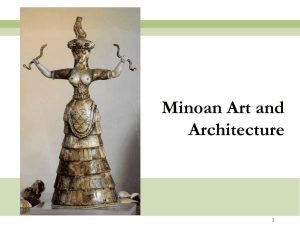

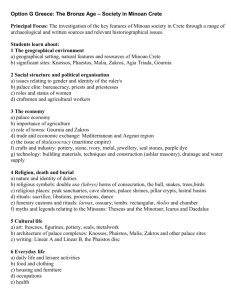

Chapter 3 Minos and the Heroes of Homer: The Art of the Prehistoric Aegean NotesThis period is the time described by the ancient Greek poet Homer in his epic poem the Iliad. Composed around 750 BC, it was unquestionably the first great work of Greek literature. In fact, until 1870 it was considered pure fiction. In the late 1800’s a wealthy German businessman turned archeologist changed this thinking. Between 1870 and his death 20 years later, Heinrich Schliemann uncovered some of the very cities Homer named. He discovered Troy and Mycenae. Successors uncovered Knossos, the legendary palace of King Minos, and the labyrinth of the famed Minotaur. Because of these discoveries and others, art historians now have an array of buildings, paintings, and to a lesser extent, sculptures that attest to the wealth and sophistication of the people who lived in the once obscure heroic age celebrated in later Greek mythology. The highest period of the ancient Aegean was not until the second millennium BC, well after the emergence of the river valley civilizations of Egypt, Mesopotamia, and South Asia. The sea dominated geography of the Aegean contrasts sharply with that of the Near East. Crete and the Aegean Islands at the commercial crossroads of the ancient Mediterranean had a major effect on their prosperity. The sea also provided a natural defense against the frequent and disruptive invasions that checker the histories of land bound civilizations such as those of Mesopotamia. Historians, art historians, and archaeologists alike divide the prehistoric Aegean into three geographical areas, each with a distinctive artistic identity. Cycladic Islands (so called because the circle around Delos) Cycladic art Early Middle Late Crete Minoan art Early Middle Late The Greek Mainland Helladic art Early Middle Late (Mycenaean) Cycladic Art Most Cycladic sculptures like many of their predecessors represent nude women with their arms folded across their abdomens. They vary in height from a few inches to almost life size. This example is about 18” high, and comes from a grave on the island of Syros. This statute is typical. It is almost flat, and the human body is rendered in a highly schematized manner. Large simple triangles dominate the form - the head, the body itself (which tapers from exceptionally broad shoulders to tiny feet), and the incised triangular pubis. The feet are too fragile and too small to support the figure. If these sculptures were used as funerary offerings, as archaeologists believe they were, they must have been placed on their backs lying down, like the deceased themselves. Whether these are statuettes or fertility figures, or goddess’ is still debated. What ever their purpose, the sculptor took great care to emphasize the breasts and the pubic area. In the Syros statute, a slight swelling of the belly may suggest pregnancy. Some of the figures were painted with eyes and mouths to go with the sculpted noses. Painted necklaces and bracelets as well as, dots on the face characterize a number of figures. Male figures also occur, often in the form of musicians, such as the lyre player from Keros. He may be playing for the afterlife but it remains unclear. Characteristic form is similar to the other statutes. Some Cycladic figures have been found in settlements and not just tombs, suggesting that the same form took on different meaning in different contexts. It is only when the context of an artwork is known can one go beyond an appreciation of its formal qualities and begin to analyze its place in art history and in the society that produces it. Minoan Art Architecture During the third millennium most settlements in the Aegean were small with only simple buildings. In contrast, the opening centuries of the second millennium (the Middle Minoan period on Crete) are marked by the construction of large palaces. This first, or Old Palace, period came to an abrupt end around 1700 BC, when the structures were destroyed, probably by an earthquake, after 1700 BC. The New Palace period (Late Minoan), the golden age of Crete, began an era when the fist great Western civilization emerged. The Palace at Knossos The largest of the palaces at Knossos, was the legendary home of King Minos. Here the hero Theseus was said to have battled with the bill-man Minotaur. According to the myth, after defeating the monster, Theseus found his way out of the maze like complex only with the aid of the king’s daughter, Ariadne. She had given Theseus a spindle of thread to mark his path through the labyrinth and then safely out again. In fact the English word labyrinth derives from the intricate plan and scores of rooms of the Knossos palace. Labrys means “double axe” and it is a reoccurring motif in the Minoan palace, referring to sacrificial slaughter. The labyrinth was the “House of Double Axes”. The Cretan palaces were well constructed, with thick walls composed of unshaped field stones embedded in clay. There is a remarkable rainwater drainage system of terra cotta pipes that run underneath the building. Painted Minoan columns, originally fashioned of wood but were restored as stone in the early 20th century, are characterized by their bulbous, cushion like capitals and distinctive shafts. The capitals resemble those of later Greek Doric order, but the shafts taper from a wide top to a narrower base the opposite of both Egyptian and later Greek columns. Painting Mural paintings are everywhere throughout the palace at Knossos. The brightly painted walls and the red shafts and black capitals of wooden columns provided an extraordinarily rich effect. The paintings depict many aspects of Minoan life (bull leaping, processions, and ceremonies) and nature (birds, animals, flowers, and marine life). Unlike the Egyptians, who painted in fresco secco (dry fresco), the Minoans coated the rough fabric of their rubble walls with a fine white lime plaster and used the true (wet) fresco method. The Minoan frescos required rapid execution and great skill in achieving quick, almost impressionistic effects. Bull Leaping at Knossos Liveliness and spontaneity characterizes the “Bull Leaping” fresco at Knossos. This fresco depicts the Minoan ceremony of bull leaping. The fresco has been restored from fragments of the original. The dark patches are original and the other restored. The Minoan artist painted the young women (with fair skin) and the male youth (with dark skin) according to the accepted ancient convention for distinguishing male and female. The young man is shown in the air, having, it seems, grasped the bull’s horns and vaulted over its back in an extremely difficult acrobatic maneuver. The painter brilliantly suggested the powerful charge of the bull by elongating the animal’s shape and using sweeping lines to form a funnel of energy, beginning at the very narrow hind quarters of the bull and culminating in its large, sharp horns and galloping forelegs. The human figures also have stylized shapes, with typically Minoan pinched waists, and are highly animated. Although the profile pose with the full-view eye was a familiar convention in Egypt and Mesopotamia, the elegance of the Cretan figures, with their long curly hair and proud self confident bearing, distinguishes them from all other figure styles. The angularity of the figures seen in Egyptian wall paintings is modified by the curving Minoan line that suggests the elasticity of the living and moving being. The Murals on Ancient Thera Paintings from Akrotiri on the volcanic island of Santorini (ancient Thera), there have been discovered frescos that are in excellent condition compared to the Knossos ones. This was due to the city being buried in volcanic pumice and ash from a major volcanic eruption, like Pompeii was in later times. The Akrotiri frescoes decorated the walls of houses, not the walls of great palaces, as at Knossos. One Theban fresco has been called Miniature Ships Fresco. It is a frieze about 17 inches high at the top of at least three walls in the so called West House of Akrotiri. Our detail shows a great fleet sailing from one Aegean port headed for another unseen port or perhaps taking part in a sea festival or perhaps engaged in a navel campaign. Such a detailed representation of the movement of ships and people from port to port does not appear again until the Column of Trajan the Roman emperor almost 2000 years later. The details of ship design and sailing reflect careful observation rather than formula. People are posed according to their role rather than following a canon. The whole composition has an openness and lightness that suggest the freedom of movement of people born to the sea. Spring Fresco Another fresco form Akrotiri captures a fresh and vital vision of the Aegean world. Nature is the sole subject with the artist’s purpose to capture the essence and joy of the surroundings rather than precise realism. Spring Fresco is the polar opposite of the Paleolithic cave painting where animals appeared as isolated figures without any indication of setting. Kamares Ware During the Middle Minoan period, Cretan potters fashioned sophisticated shapes using the newly introduced potter’s wheels. The vessels are named for the cave on the slope of Mount Ida where they were first discovered, and have been found in quantity at other sites. Kamares ware has a distinctive and polychromatic style. Creamy white and reddish brown decoration is set against a rich black background. In our example, the central motif is a great leaping fish and perhaps a fish net surrounded by a host of curvilinear abstract patterns including wave and spirals, evoking the life of the sea and compliment the form of the vessel. The Octopus Jar This Late Minoan Marine style jar is a masterful realization of the relationship between a vessel’s decoration and its shape. This Vessel differs from Kamares Ware in color, reversing the creaming white background and making the black into silhouette decoration. This remained the norm in Greece, until about 530 BC when, albeit in a very different form, light figures on a dark background emerged once again as the preferred manner. Sculpture The Harvester Vase is probably the finest surviving example of Minoan relief sculpture. While depicting a harvest scene, the Minoan artist shunned static repetition in favor of a composition that bursts with the energy of its individually characterized figures. The relief shows a riotous crowd singing and shouting as they go to the fields. The artist vividly captured the forward movement and lusty exuberance of the youths. This is one of the first instances in the history of art of a sculptor showing a keen interest in the underlying muscular and skeletal structure of the human body. The degree of animation of the human face is without precedent in ancient art. Snake Goddess In contrast to Mesopotamia and Egypt, no temples or monumental statues of gods, kings, or monsters have been found in Minoan Crete. Large wooden images may have existed at one time, but what remains of Minoan sculpture is small in scale. One such example is a small in scale faience (glazed earthenware) statuette known as the Snake Goddess, from the palace at Knossos. It is one of several similar figures that some scholars believe may represent mortal attendants rather than deity. However the exposed breasts suggest a fertility image, which is often seen as divine. Holding the snakes and a leopard sitting on her head implied power over the animal world also seems appropriate for a deity. If this is a goddess, it is yet another example of how humans fashion god in their own image. Mycenaean Art Mycenaean power developed on the mainland in the days of the new palaces on Crete, and by 1500 BC a distinctive Mycenaean culture was flourishing in Greece. The destruction of the Cretan palaces left the mainland culture supreme. Although this Late Helladic civilization has come to be called Mycenaean, Mycenae was but one of several large citadels. The best preserved of these citadels are the fortified palaces at Mycenae and at Tiryns. Both were built around 1400 BC and were burned, along with all the others, between 1250 and 1200 BC, when the Mycenaeans seem to have been overrun by Northern invaders or internal warfare. In the second century a man named Pausanius authored a guidebook to Greece. He visited the site of Tiryns and marveled at the towering fortifications and considered the walls of Tiryns as spectacular as the pyramids of Egypt. In fact the Greeks of the historical age believed mere humans could not have erected such edifices and instead attributed the construction of the great Mycenaean citadels to the mythical Cyclops, a race of one-eyed giants. Historians still refer to the huge roughly cut stone blocks forming the massive fortification walls a Cyclopean Masonry. Tiryns The heavy walls contrast greatly with the open Cretan palaces and clearly display a defensive character. The walls of Tiryns average 20 feet in thickness. The cantilevered stones in the passageway are held in place only by their own weight (often several tons each), smaller stones used as wedges, and clay to fill in spaces. This primitive yet effective scheme possesses an earthy monumentality. It is easy to see how a later age came to believe that the uncouth Cyclops were responsible for these massive but unsophisticated fortifications Mycenae’s Lion Gate The Lion Gate is the outer gateway of the stronghold at Mycenae. It is protected on the left by a wall built on a natural rock outcropping and on the right by a projecting bastion of large rocks. Any approaching enemies would have had to enter this 20 foot wide channel and face Mycenaean defenders above them on both sides. The gate itself is formed of two great monoliths, acting as posts, which is capped with a huge lintel. Above the lintel, is formed a corbeled arch, leaving an opening that lightens the weight the lintel carries. This relieving triangle is filled with a great limestone slab where two lions are carved in high relief and stand on the sides of a Minoan type column. The whole design admirably fills its triangular space, harmonizing in dignity, strength, and scale with the massive stones that form the wall and gate. The gate and walls were constructed a few generations before the presumed date of the Trojan War. Treasury of Atreus The wealthy Mycenaeans were buried outside the citadel walls in beehive shaped tombs covered by enormous earthen mounds. The best preserved of these tholos tombs is the so called Treasury of Atreus, which already in antiquity was mistakenly believed to be the repository of the treasure of Atreus, father of Agamemnon and Menelaus. The tholos is composed of a series of stone corbelled courses laid on a circular base and ending in a lofty dome. About 43’ high, this is the largest known vaulted space without interior supports that had ever been built. This achievement was not surpassed until the Romans constructed the Pantheon almost 1500 years later, using a new technology - concrete construction - unknown to the Mycenaeans. Funerary Mask The Mycenaeans laid their dead on the floors of shaft graves with masks covering their faces. This gold mask is one of the first known attempts in Greece to render the human face at life size. Features were handled with care, but it is not known if the artists tried to do specific portraits. The mask was made of beaten gold using the repousse’ technique. The Warrior Vase Pottery continued even after the fall of the Mycenaean palaces. The Warrior Vase is a krater style (bowl for mixing wine and water) and an example of Late Bronze Age painting and is named for the frieze of warriors marching off to war. The painting has no setting or context for the figures. This simplification of narrative is paralleled in other painted vases by the increasingly schematic and abstract treatment of marine life. The octopus, for example eventually became a stylized motif composed of concentric circles and spirals that were almost unrecognizable as a sea creature. Three centuries after the fall of Mycenae, the art of figure painting had been forgotten. With the destruction of the Mycenaean palaces around 1200 BC, Greece was plunged into a “Dark Age,” when the arts of painting, carving, and building, and even writing almost disappeared. The historical Greeks looked back on the achievements of their Minoan and Mycenaean predecessors with awe, but in time they would surface them and put their stamp on Western civilization and Western art forever.