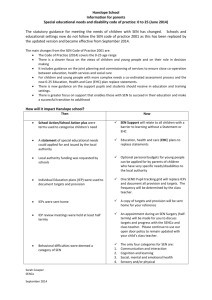

An examination of current provision of education for children with

advertisement