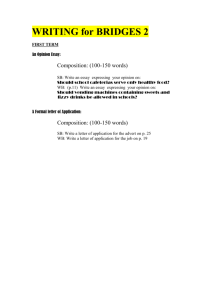

Good Writing Guide

advertisement