Cornelia Vismann`s Files: Law and Media Technology

advertisement

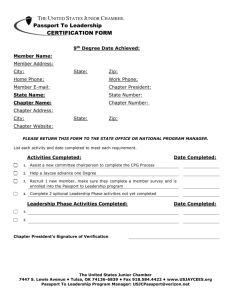

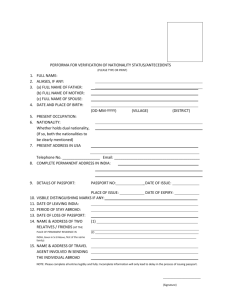

Richard Burt: ‘Shelf-Life’. To see European literature as a whole is possible only after one has acquired citizenship in every period from Homer to Goethe. This cannot be got from a textbook, even if such a textbook existed. One acquires the rights of citizenship in the country of European literature only when one has spent many years in each of its provinces and has frequently moved about from one to another. One is a European when one has been a civis Romanus. E.R. Curtius, Eurpean Literature and the Latin Middle Middles Ages, 1952, p. 12 My article concerns ‘the biopolitical archive’, or what I call ‘shelf-life’, namely, the relation between persons and paper, between the book as auto- or bio-graph and the book as storage unit. The article falls into three parts. Firstly, I begin with an analysis of a U.S. Government video entitled ‘How a US Passport is Made’ (2009). The passport is a figure of the processing of citizenship through paper, yet in its materiality as a ‘book’ it offers resistance to narrative: the passport is a hybrid, both a printed book and yet also a kind of microchip e-book that only machines can ‘read’. By attending to the sediment of the passport as a material book or thing, I rephrase questions about bare life, biopolitics, citizenship, the polis as questions about media storage by the State. The question of biopolitics is also a question of biblibiopolitics, of the ways in which citizens are alienated from their own data. Stored as data, persons are turned into citizens. Citizenship passes though the person in enabling him or her to pass through customs, unsettling distinctions between guest and host, alien and host, and the inhuman outside citizenship (equated with aliens such as animals, vermin, threats, viruses, ‘flus, etc), hostage and hostage taker. Citizenship is thus not a securing of human rights but a host-age taking. In the second part of my essay, I turn to concrete cases to show more fully how an analysis of biobiblioplitics necessarily concerns the archive—the routing of persons into paper and of paper into persons. Here I discuss a passport sequence about Holocaust victims in Alain Resnais’ Night and Fog (1955) in conjunction with a sequence in which a book is processed as prisoner of the Bibliothèque nationale de France in Resnais’s Toute la memoire du monde (1956). In the third part of the essay, I turn to the theoretical context offered by Derrida’s reading of Benjamin in relation to the archive in order to problematise and develop the idea of the hybrid textual form indicated by the figure of the passport. Benjamin’s essay, ‘Books by the Mentally Ill’, concludes with reference to the failure of a manuskript to be published as a book as a process equated with obtaining a passport, recording it by tabling its contents as if he were hoping it and others like it might thereby slip by the passport controls of the biblio-polis. Comparatively, in ‘Fichus’, Derrida writes of a dream he as about writing book about Benjamin he no longer has time to write but can only deliver as a TV guide to the chapters of the virtual books he won’t get around to writing. Derrida refuses to play either the librarian, consigning the text to a taxonomic pigeon-hole, and refuses to play the philologist, instead reading Benjamin’s letters as disseminated, unaddressed or readdressed, irreducible to an archival or biological time or place where they could be rendered readable. Thus, reading as refiling or reshelving becomes a way of living ‘bare life’ virtually, as the archive allows for new kinds of self-storage that not only default the archive toward the future rather than the past but turn even the most easily accessible and well-preserved document into a text yet to be read.