home - Department of Political Science

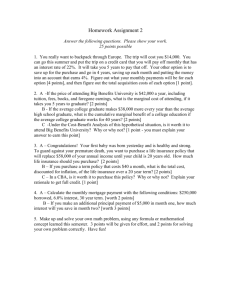

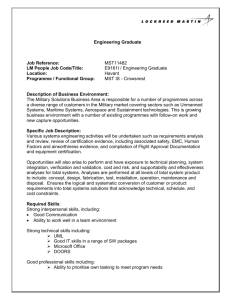

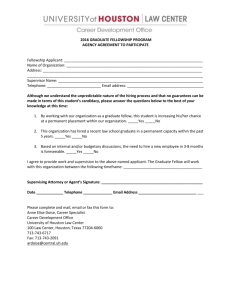

advertisement