Pareto`s principle of oil

advertisement

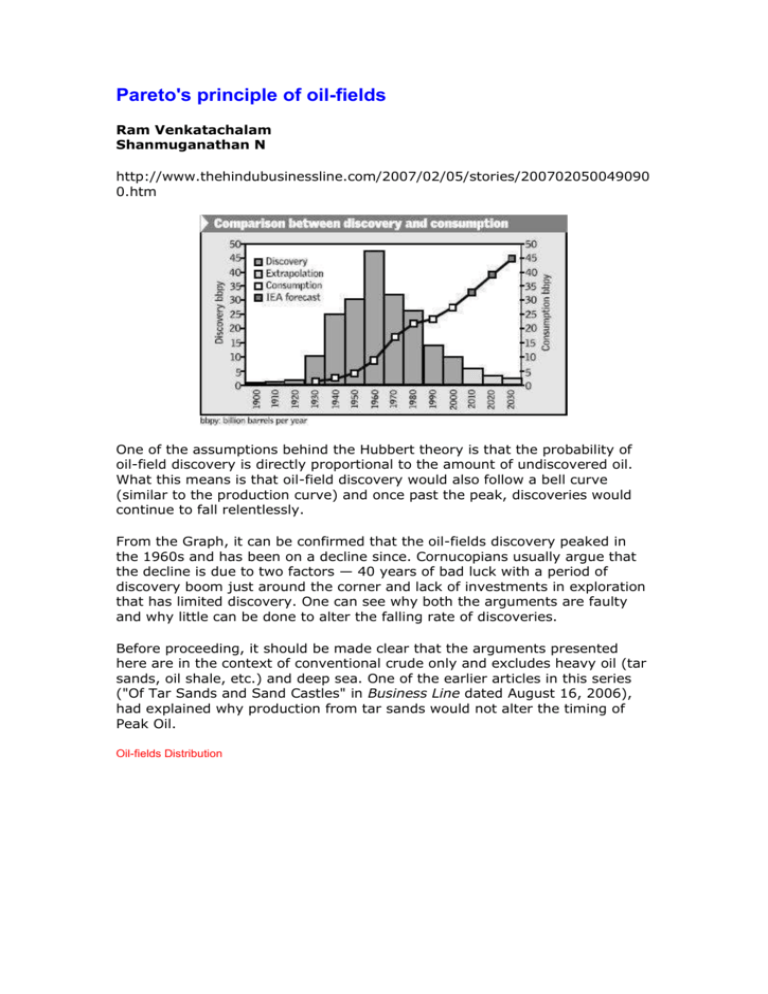

Pareto's principle of oil-fields Ram Venkatachalam Shanmuganathan N http://www.thehindubusinessline.com/2007/02/05/stories/200702050049090 0.htm One of the assumptions behind the Hubbert theory is that the probability of oil-field discovery is directly proportional to the amount of undiscovered oil. What this means is that oil-field discovery would also follow a bell curve (similar to the production curve) and once past the peak, discoveries would continue to fall relentlessly. From the Graph, it can be confirmed that the oil-fields discovery peaked in the 1960s and has been on a decline since. Cornucopians usually argue that the decline is due to two factors — 40 years of bad luck with a period of discovery boom just around the corner and lack of investments in exploration that has limited discovery. One can see why both the arguments are faulty and why little can be done to alter the falling rate of discoveries. Before proceeding, it should be made clear that the arguments presented here are in the context of conventional crude only and excludes heavy oil (tar sands, oil shale, etc.) and deep sea. One of the earlier articles in this series ("Of Tar Sands and Sand Castles" in Business Line dated August 16, 2006), had explained why production from tar sands would not alter the timing of Peak Oil. Oil-fields Distribution A study of the oil-field production data reveals the Pareto's principle — that is, a very small percentage of the oil fields contribute a disproportionately large share of the production. As the inverted-triangle diagram shows, of the more than 4,000 oilfields in production today, less than 120 (3 per cent) contribute nearly 48 per cent of the output. Discovery of giant oilfields The surprising realisation is that the bulk of the giant oilfields was discovered during the 1950s and 1960s with technology no more sophisticated than hand-tools. Moreover, the 14 elephant oil-fields (those with a production greater than 0.5 mbpd) were all discovered a long time ago and these fields now have an average age of 55 years and are mostly in decline. Dr Colin Campbell of ASPO explains this falling rate of discovery by stating that "... the whole world has now been seismically searched and picked over. Geological knowledge has improved enormously in the past 30 years and it is almost inconceivable now that major fields remain to be found". In some sense, the Cornucopians are correct about the "bad luck" part — not as in their reference to the past few decades but rather with respect to what awaits the world of exploration. Investments in Exploration The claims about fall in exploration activity are also not entirely correct. On account of the oil crises of the 1970s, a massive investment boom in the exploration industry followed, in which the number of rigs increased from a little over 2,000 in 1970 to more than 5,500 by 1980. This increased exploration did not evidently result in greater discoveries, for reasons explained above. However, it is true that post-1980, the world saw a major decline in the exploration sector with the number or rigs today at about 3,000. Consequently, the drilling industry had a two-decade bear market, with the result that only50 rigs/year can be manufactured today. So, even to reach the 1980s level of exploration activity, we will require another 50 years at current production levels. Not that it would guarantee anything in return, but it indicates that exploration capacity just cannot be increased significantly in the foreseeable future. With the increase in oil prices in the last few years, the oil majors have increased their exploration spending, but what they are discovering is that this increased spending does not necessarily translate into reserve additions. Despite a $65-billion increase in capital spending of the oil majors, reserve additions actually fell in 2005 compared to 2004. The 36 per cent increase in upstream investments resulted in a very marginal increase in reserves. This is nothing more than the law of diminishing marginal returns operating that started in the 1960s, at the peak of the discovery curve. In fact, there is strong evidence that the oil majors themselves recognise this. The cash payouts to shareholders in the form of dividends and share buybacks have approached 50 per cent of the capital outlays. So the question is why the oil majors are not investing in additional exploration at a time of such high prices and profits. The answer is that they are behaving in a manner that is consistent with their shareholders' interests — that is, instead of investing in exploration that is not going to provide meaningful returns, as evidenced, they are returning the surplus cash to the owners. Comparing oil-fields with land In some ways, the discovery of oil-fields can be compared to that of the landmasses. All of the inhabitable continents and large islands were discovered as early as 40,000 years ago, with very elementary sea-craft. Some of the smallest and most remote Polynesian islands were discovered as early as 900 AD and even the most advanced remote-sensing satellite today has not discovered any other islands — not because there is anything wrong with the technology, but simply because there is nothing left to be discovered in the first place. In terms of oil-field discovery today, we are at a stage comparable to when the continents and other large islands have been discovered. Maybe we will discover some medium-sized oil-fields, but these are not even going to compensate for the decline in production from the elephant oil-fields, let alone increase the overall capacity. (The authors are Directors at Benchmark Advisory Services. They can be contacted at ram.venkat@benchmarkconsulting.in and shan.sundaram@benchmarkconsulting.in respectively.)