a fool and her mummy

advertisement

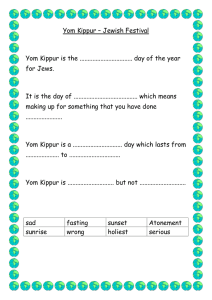

Published: Sunday, April 11, 1993 Section: TROPIC Page: 11 A FOOL AND HER MUMMY KATHY ELLISON, The Miami Herald The two occasions each year on which my mother is most vividly herself are Yom Kippur and April Fools' Day. On Yom Kippur, the Jewish Day of Atonement, she fasts and weeps, haunts the synagogue, and self-effacingly makes sandwiches for my situationally agnostic father. On April Fools' Day, she reminds my father and, most of all, me, that selfeffacement is her choice, and it doesn't mean she isn't smarter than us both. Bernice Bender never defied her generation's expectations. At 19, she dropped out of college to marry a medical student and bear him four children. She stayed home to raise us, a closely tended brood of three future doctors and one future newspaperwoman, until I, the youngest, was old enough for high school. Only then did she return to school herself, and then spent 10 years coaching children with learning disabilities in one of San Francisco's poorest neighborhoods. She is now in her 60s, and her life remains a portrait of cheerful self-sacrifice. Her friends praise her consummate tact and consideration. But few outside our family have witnessed the brilliance of her wicked genius, which appears, like a rare flower, just once a year. My mother and I have almost always been close, yet in our life choices we are far apart. At 35, I'm married but childless, focused on my job as a foreign correspondent. A few years ago, I moved to Mexico for work, and this year even farther, to Brazil. All the while, I have noticed my mother's April blooms grow more exotic, as if to compensate for all the miles between us. In the first spring of my absence, for instance, I was shocked to find among my mail a neatly printed bill, on professional letterhead, for $1,200. The sum represented the cost of a couch that one of my mother's friends, an interior decorator, had loaned me three years earlier. Not only had I taken the couch with me when I moved, I had recently paid a couple of hundred dollars to have it re- upholstered, a little detail I may have mentioned to my mother. Guilt, shame and financial anxiety washed over me as I stared at the invoice, which arrived April 1 -- or so I thought, unwilling, at least at first, to imagine my own husband conspiring with my mother to plant it in my mailbox. The next April Fools' Day fell in 1990, during a week when I was visiting my parents in California and drafting an article about Fidel Castro for The Atlantic Monthly. It was my first assignment for such a major magazine, and I was full of apprehension, though I felt sure of my argument. Castro, I maintained, would stay in power for years, despite the then- conventional wisdom that his fall was imminent. On the critical morning, I strolled in to breakfast, fully conscious of the date and determined to remain on guard. That didn't stop me from screaming, however, at the three-inch, front-page headline in what looked at first exactly like The San Francisco Chronicle: CUBAN REVOLUTION! CASTRO OUT!!! Another year passed, and with it, my conviction that my mother's natural reserve would keep her from recruiting the aid of total strangers for her tricks. I was vacationing at a rustic hotel in the Pacific resort of Zihuatanejo that April when my editor at The San Jose Mercury News in California reached me with an urgent message. He had spent nearly an hour trying to get through on the hotel's one line, he told me later, but persisted, a man with a mission. He wanted to beg my apology: Through no fault of his, some other editor had put the wrong byline on a long series of articles to which I had devoted several weeks. At this point, the reasonable reader must be wondering why I did not rage at my mother for crashing in on my professional life, for violating boundaries with impunity, for infantilizing me with my bosses. And in fact, I did rage. I did. But quietly. To myself. To my husband. Never to my mother. I was stopped there by habit, and by awe. To explain the habit first: The convergence of trickery and affection, which goes along so well with almost never saying anything directly, is an abiding pattern of my family's life. My older brother, a Massachusetts psychiatrist, recently courted a young woman by rigging a tiny explosive beneath her toilet seat. He's the first to concede the tactic was hardly your Hallmarkcard kind of expression of affection. Yet neither he nor I nor even the young woman ever doubted its romantic inspiration. My mother's yearly tricks carry their own fierce and distinctive signals. They are aggressive: She will not be excluded from my life. They are provocative: Do I really think my choices -- my pride, my work, my paycheck -- are beyond her challenge? And they are proud: Look how clever she is; she could have been anything she wanted, if she had only wanted it enough. Yet just like my brother's small bomb, my mother's pranks express as best she can her desire for an intimate connection -- which surely is love, gritty and complicated as it may be. I see that more clearly the older I grow, and the farther I go away from her. And that is where my awe comes in: awe at my mother's peculiar mastery. For April Fools' Day, as she well knows, is an opportunity for true art. Its best tricks manage to tweak but not insult, stun but never terrify. At its best, it gives Foolers the chance to show how well they know their prey, while also creating, if only for a moment, a private and supremely sheltered world where all fear is short-lived, and -- thanks, of course, to the Fooler -- everything always turns out OK. KATHY ELLISON is The Herald's correspondent in Brazil.