PEARCE_CoPv.08_Pt1 - School of Literature, Media, and

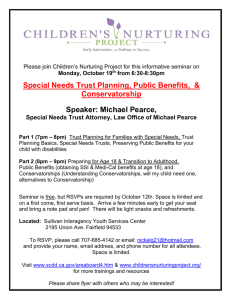

advertisement