D, DP form and discourse accessibility

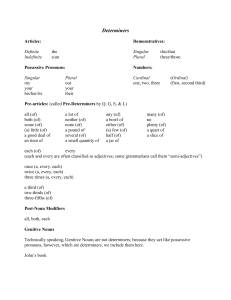

advertisement

D, DP form and discourse accessibility Jocelyn Ballantyne, University of Utrecht The DP hypothesis (Abney 1987) has led to many analyses in which pronouns are treated as determiners. Cross-linguistically, determiners serve as the locus of the referential phi-features (Ouhalla 1991) that participate in agreement processes. A noun is not referential, but acquires referentiality via the DP; determiners, including null D, are a natural class because they carry the person features necessary for referential index (cf. Ouhalla 1991; Cohan 1998). Classifying pronouns with determiners also allows nominals occurring with pronouns to be treated as NP complements rather than appositives, as in constructions like English We linguists, you kids, and that devil (Zwarts 1994). An issue, however, that arises in many syntactic treatments is the fact that determiners are not uniform in complement selection. While some determiners can appear with or without an overt NP complement, others are barred from appearing with an overt NP complement (‘intransitive’or ‘strong’ Ds, e.g., in English: *I linguist, *She linguist), others cannot appear without an NP (‘obligatorily transitive’ Ds, e.g., in English, the, a(n), Ø). The paper to be presented develops an earlier proposal that the complement selection of determiners is related to the use of the determiners in discourse. It connects the evident syntactic form of the DP to the level of cognitive accessibility of the referring expression in discourse (Prince 1981; Gundel et al. 1993). Specifically, when determiners require complements, they are associated with lower levels of cognitive accessibility in discourse (unused or brand new for the English examples appearing in Table 1 below) -- these are also the DPs most likely to be connected to focus. In referring expressions with the highest levels of cognitive accessibility scale, we find determiners that bar co-occurrence with an NP (active in Table). Table 1: Cognitive state and form of referring expression (taken from Prince 1981) HIGH ↑ ↓ LOW Cognitive state active accessible unused (familiar) brand-new, anchored brand-new, unanchored form of expression clitics, unstressed pronouns definite NP definite NP indefinite, specific NP indefinite NP Examples she, he, her, him, it, etc. I, you, that, the cat, John the boss, John a guy at work a guy Languages vary in how cognitive accessibility of referring expressions is marked, and languages vary in the kind of overt DPs that they allow. In languages like English, the more ‘active’ the referent, the more likely it is to be expressed by a DP without an overt NP. In head-marking languages, arguments appear as agreement markers or clitics, and full DPs are optional, restricted to a “use induc[ing] a certain kind of emphasis on the denoted individual” (Wiltschko 2002) – a use related to discourse focus, and thus a lower level of cognitive accessibility. The general prediction is that the realization of DPs within a language will align with the cognitive accessibility scale cross linguistically. The DPs occurring at the highest levels of accessibility indicated in Table 1 can be used felicitously as arguments only when they have known unique referents in the discourse context; these are the so-called intransitive determiners. All remaining DPs, on the other hand, can be used as arguments without specific unique referents, in a generic or indefinite sense (even with ‘definite’ determiners, e.g., You coffee drinkers can sure be testy, The/That first cup is always the best). The ‘intransitive’ determiners thus differ from other (in)definite determiners in that they must have a known unique referent. ‘Obligatorily transitive’ determiners (e.g., in English the, a(n), Ø), correspond to the lower levels of cognitive accessibility. While arguably specified for (3rd) person, they do not provide fully referential indices on their own – an NP is needed to complete the specification of their phi features (Ouhalla 1991) and the required referentiality of the DP. The determiner the, for example, requires number and some feature like +HUMAN (Zwarts 1994 inter alia), or perhaps +ANIMATE, to fulfill its referential index, while a, already singular, requires only +ANIMATE. Without these, agreement, binding, co-reference and semantic restrictions on predicates cannot operate. On the other hand, ‘optionally transitive’ determiners (in English, the demonstratives and plural personal pronouns), may serve in argument position without an overt NP (e.g., Youi must ask yourselvesi the right questions). These determiners can get the features required to complete their referential index from the context. A determiner that appears without an overt complement is one that picks up the features of its referential index from the discourse context. This gives us the means to define two categories of determiners that should be attested cross linguistically: 1. UNIQ: a D is UNIQ if and only if its referential index maps onto a unique entity or set of entities present in the discourse context. 2. DISC: a D is DISC if features of its referential index can be determined from discourse context. Figure 1: Determiner types with cognitive accessibility scale DETERMINERS (1ST/2ND/3RD PERSON) DISC UNIQ HIGH LOW Figure 1 shows that UNIQ Ds are a subset of DISC Ds, and that determiners associated with the lowest levels of cognitive accessibility on cognitive accessibility hierarchies are not DISC Ds, while determiners associated with the highest levels are UNIQ Ds. Cross linguistically, we should thus expect to find (1) that UNIQ Ds are also DISC Ds; (2) that UNIQ Ds, barring noun phrase complements, are associated with the highest levels of cognitive accessibility; (3) that Ds requiring noun phrase complements are associated with the referring expressions of the lowest level of accessibility; and finally, (4) that gaps in the determiner system of a language will occur at either end of the proposed hierarchy, but not in the middle. These generalizations are to be supported by a discussion of referring expressions from Greek, Polish, Hebrew, Turkish, and Dutch. Selected References: Abney, Steven P. (1987) The English NP in its Sentential Aspect. Dissertation, MIT, Cambridge, MA. Cohan, Jocelyn (1998). Semantic features of determiners: toward an account for complements of D. In A. Dimitriadis, H. Lee, C. Moisset and A. Williams. Proceedings of the 22nd Annual Penn Linguistics Colloquium. Gundel, J.K., Hedberg, N., Zacharski, R. (1993) Cognitive states and the form of referring expressions in discourse. Language 69: 274-307. Ouhalla, Jamal. (1991) Functional categories and parametric variation. London: Routledge. Prince, Ellen (1981) Toward a taxonomy of given-new information. In Cole, ed., Radical Pragmatics, New York: Academic Press. 223-255. Wiltschko, Martina (2002). “The syntax of pronouns: evidence from Halkomelem Salish” Natural Language and Linguistic theory 20:157-195. Zwarts, Joost (1994). Pronouns and N-to-D movement. In M. Everaert, B. Schouten and W. Zonneveld, eds., OTS Yearbook, Utrecht: 93-112.