III

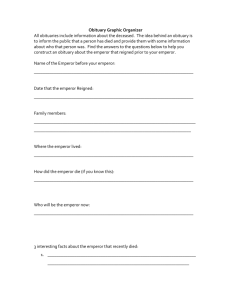

advertisement