A (Rough) Overview of Philosophy and Ethics

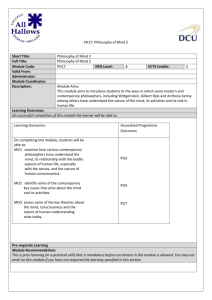

advertisement

A (Rough) Overview of Philosophy ______________________________________________________________________________ 1. What is Philosophy? 1.1 Philosophy and Other Things The best way to approach the question, “What is philosophy?” is to see how philosophy compares with other human activities. Here’s a short list of some human activities we might consider: Philosophy Chemistry Soccer History Sociology Acting Mathematics Parenting Swimming The first thing to notice about this list is that some of the activities it contains are forms of inquiry (i.e. they are attempts to discover things about the world) and others are not. For example, consider soccer. What a soccer player is out to do is develop their physical prowess and athletic skill such that through working their team they score more points than the opposing team. While this may require learning a good deal of things (for example, about physical training, the rules of the game, tactics), soccer players are not fundamentally aiming to add to human knowledge but to put it to use and winning games. Fields of inquiry, like chemistry, differ in this respect. A successful chemist is not just one who knows a good deal of chemistry, but one who adds to the list of things we know about chemistry. So one thing we should do up front, is arrange our list of human activities into those which are forms of inquiry and which are not: Inquiry Chemistry History Sociology Mathematics Non-inquiry Soccer Acting Swimming Parenting So where does philosophy fall on this arrangement? It turns out that philosophy is more like chemistry than soccer. Philosophers, like chemists, are out to discover certain truths about the world. This is not widely realized because in ordinary conversation the term “philosophy” is often just used to refer to someone’s religious, ethical, and political opinions. For example, the social networking website Facebook recently reorganized the profiles of its users such that their religion and political views fall under a category labeled “philosophy”. While using the term “philosophy” in this way is mostly harmless, we should not forget that philosophy also a term used to refer to a specific field of professionals working to answer certain questions about our world. So if philosophy is a field of inquiry like chemistry, what are philosophers trying to find out? Chemists try and answer questions about chemicals and chemical reactions, historians about the events of the past, sociologists about groups of people and their culture, mathematics about numbers, and so on. So what sort of questions are philosophers out to answer? To figure this out, we need to first look at the method most other fields of inquiry use in trying to discover things about the world. Specifically, most fields of inquiry are empirical. A chemist inquires into the world by experiments, a historian by going out and making observations of ruins and examining books and relics from the past, sociologist by taking surveys, and so on. What all of these fields share, is that they can’t be done by sitting in your armchair and thinking really hard. They all require that chemists, historians, and sociologist go out into the world and check to see what it’s like—and then think really hard. These fields of inquiry all once went by the name natural philosophy, but for the last 100 years or so we’ve called them the sciences. A science is a human activity of inquiry that discovers truths about the world through going out into the world and gathering empirical data (experiment, observation, surveys, and so on). Philosophy is not empirical. In this way, philosophy is more like mathematics than chemistry. In fact, one way to think about philosophy and mathematics is as the two fields of inquiry that take on whatever questions cannot be solved through the gathering of empirical data. Mathematicians are given whatever non-empirical questions involve numbers and calculation, while philosophers take on the rest of the lot. So one last way in which we can arrange our list of human activities, is by dividing forms of inquiry into those which are empirical and those which are not: Inquiry Empirical Chemistry History Sociology Non-inquiry Non-empirical Philosophy Mathematics Soccer Acting Swimming Parenting Mathematicians don’t solve difficult mathematical questions by taking surveys or performing experiments. There is no mathematics laboratory. Mathematicians have to simply think mathematical problems through very carefully. Often, they make mistakes, which is why they publish their work in professional mathematics journals so that other mathematicians can check their work. Professional philosophers work in the same way. 1.2 An Example of Philosophy So, other than mathematical questions, what can’t be discovered through observation and experiment? What sorts of questions do philosophers try and solve? Let’s consider a question philosophers take themselves to have solved. Consider the following question: Are selfless actions possible? The answer to this question might seem obvious. Of course it’s possible to act selflessly. Apparent selfless acts range from the mundane (e.g. someone who stops and helps a stranger collect up paperwork they’ve dropped; volunteers who participate in unpaid blood donation) to the extraordinary (e.g. in 2007 a New York man began convulsing and collapsed into the path of an oncoming subway, 50-year old construction worker Wesley Autrey saved the man by leaping down onto the tracks and holding the man down while the train passed inches from both of their heads). Perhaps no one is as selfless as they think they are and perhaps people often say or think they are acting selflessly when an act is actually covertly in their selfinterest, but at least some of the time people do appear to act selflessly. However, consider the following argument: Argument Against the Possibility of Selfless Acts: Even when I help someone else, I do so because what I most desire is helping them. What this means is that even when I seem to be doing something selfless for others, I am still just acting to fulfill a desire of my own. I am always just doing what I most desire. Therefore, people are always selfish and there is no such thing as a selfless act. Upon first hearing the above argument, many if not most people take it to be obviously correct. However, once we think carefully about it, we can see that it is wrong. Philosophers have discovered a number of problems with it, but let’s take just one. Consider a case that it would be very difficult for someone who denies the possibility of selfless acts to account for. Say a soldier throws himself on a grenade to prevent others from being killed. It does not seem that the soldier is acting selfishly. It is plausible that, if asked, the soldier would have said that he threw himself on the grenade because he wanted to save the lives of others or because it was his duty. He would deny as ridiculous the claim that he acted in his self-interest. Can someone who denies selfless actions are possible claim that this soldier actually acted selfishly? Someone who claims selfless actions to be impossible might reply that perhaps the soldier threw himself on the grenade because he could not bear to live with himself afterwards if he did not do so. He has a better life, in terms of his own welfare, by avoiding years of guilt. The main problem here is that the guilt the soldier would be avoiding presupposes that the soldier selflessly desires the lives of others. Which is to say, the reason why the soldier would feel guilty if he didn’t throw himself on the grenade is because he selflessly cares for others. If he didn’t, he wouldn’t feel guilty for not throwing himself on the grenade. We ordinarily think there is a significant difference in selfishness between the soldier's action and that of another soldier who, say, pushes someone onto the grenade to avoid being blown up himself. We think the former is acting unselfishly while the latter is acting selfishly. According to someone who denies selfless actions to be possible, our ordinary way of thinking is wrong. Both soldiers are equally selfish, since both are doing what they most desire. However, there is something importantly different about the desires of one soldier from the other. Both soldiers might be doing what they most desire, but what one soldier most desires is the wellbeing of others while what the other soldier desires most is his wellbeing. What someone who claims selfless acts to be impossible gets wrong, is in its understanding of selfishness. Being selfish isn’t doing what you most desire, being selfish is about what you most desire. A selfish person desires their own life and wellbeing far above all others, while a selfless person desires the wellbeing of others over their own. That is why the selfless soldier throws himself on the grenade and why he would feel guilty if he didn’t. It is also why the selfish soldier throws someone else on the grenade and wouldn’t feel guilty about doing it. Philosopher William James had a nice way of summarizing the mistake the denier of selfless action makes. When I drive to class I always burn fuel, but my goal in driving to class wasn’t to burn fuel, it was to get to class. Likewise, when we act we might always be doing what we most desire, but our goal was not to do what we most desire. And our goal might be a selfish one or a selfless one. Just because I always do what I desire most doesn’t mean that I am selfish, it’s a matter of what I most desire. The point isn’t that we shouldn’t be selfish or that we should be selfless. The point is that the denier of selfless action is wrong that we can only act selfishly. In fact, we can do both. Which one we should do is another question entirely. Arguments that selfless action is impossible are good examples to illustrate the field of philosophy because it involves a question (“Is it possible to act selflessly?”) that cannot be solved by experiment or observation. When people seem to act selflessly, they might not be since they are still always acting to fulfill their own desires. However, by thinking it though we realize that the argument for the impossibility of selfless action is flawed. It involves a confusion about what selfishness is. Being selfish isn’t doing what you desire most, it is in desiring most your own wellbeing and not that of others. The possibility of selfless action is an example of a settled philosophical question. Professional philosophers have worked hard thinking about the question, and come to agree that we can act selflessly. In the process, they have also clarified our understanding of what it means to be selfish. These are the sorts of things philosophers inquire about and try to discover answers for. Things that instead of observation or experiment, require careful thought—and this was exactly the case for the possibility of selfless action. You might not have noticed it, but in addition to the question of the possibility of selfless action, we have also been solving another philosophical question. What is the difference between soccer, chemistry, mathematics, and philosophy? Unlike soccer, philosophy is a field of inquiry more like chemistry and mathematics. However, unlike sciences like chemistry, philosophy and mathematics are non-empirical. And lastly, unlike mathematics, philosophy is the field of non-empirical inquiry that attempts to discover truths about the world beyond those involving numbers and calculation. 1.3 Misconceptions about Philosophy Now that we have an understanding of what the field of philosophy is and examined a specific example of a piece of settled philosophy, now we are in a position to face head-on several of the widespread misconceptions about philosophy. 1.4 Purpose of Philosophy Here’s a question worth ending on, “Why do philosophy?” To begin with, notice that this question itself probably qualifies as philosophical. Without just going about your life unreflectively it is hard not to run into philosophical questions. Even stopping to consider whether one should care about philosophy already involves you in doing it. Second, we should compare this question with similar questions we could ask about other fields of inquiry, like “Why do mathematics?” For starters, many people care about inquiry just because they find it important that we know things about the world. However, others only care about fields of inquiry like mathematics or chemistry because of the practical technologies these fields enable us to produce. Will answering philosophical questions like “Is it possible to act selflessly?” enable us to build better technology or is philosophy just knowledge for knowledge’s sake? Maybe that would be enough to make a number of people care about philosophy, but not everyone. Surprisingly, answering philosophical questions has real practical consequences. Two examples: (1) The right method of a science is not something we can discover through science. In this way, all of the technology produced by answering scientific questions also relies on answering certain philosophical ones. For instance, take the case of Einstein’s 1905 discovery of the theory of relativity in physics. When Einstein developed his theory he knew about the speed of light being constant and his theory offered an explanation for why it stays constant. That is, Einstein offered a theory that explained a mystery that scientists had been struggling with for a while. However, scientists did not take this to be enough to prove the theory of relativity true. Instead, it wasn’t until many years later when it was discovered that Einstein’s theory also predicted that during a certain 1919 eclipse, that stars behind our Sun would appear on the side of our Sun because of the way our Sun curves the space around it. Once this unexpected prediction proved correct, Einstein’s theory became widely accepted. The next day the New York Times ran the headline “Einstein’s Theory Triumphs”. What this illustrates is how by current scientific methodology, a theory that makes unexpected predictions is treated as more likely to be true than one that merely explains mysteries we already knew about. However, this is certainly odd. Both the speed of light remaining constant and the 1919 eclipse are pieces of evidence supporting Einstein’s theory. Why would the order of when we obtained these two pieces of evidence matter for how much they count in favor of Einstein’s theory? If Einstein had developed his theory after 1919 would it be less likely to be true simply because it came after we had evidence for it? This is a difficult question about how science should work and how scientists should weigh evidence: “Should predictions count more than explanations or should all evidence count the same no matter when we obtained it?” Furthermore, this is not a scientific question, but a philosophical one. It is not a question that can be solved though empirical inquiry because it is a question about how empirical inquiry should work; we can’t use science to discover how science should proceed! Solving scientific questions depends on questions about the correct method of science, and those questions happen to turn out to be difficult philosophical questions that our only way of solving is by thinking carefully about what evidence is and how evidence works to reveal the truth. In this way, philosophy does contribute to the practical improvement of our lives and is more than merely seeking knowledge for knowledge’s sake. Answering non-empirical questions about how evidence works and its relation to truth is required if we are to solve all of the scientific questions which provide us with the technological advances we enjoy. New York Times Nov 10, 1919 Not the photo the New York Times published, but the one they should have. (2) Another way in which philosophy has a real practical effect on our lives is when it deals with questions like “What is right?” and “What is wrong?” Take, for example, the fact that even if something bad happens, we ordinarily think that someone hasn’t done anything wrong if what results was completely out of their control. Which is to say, blame isn’t a matter of luck. If a doctor gets stuck on an elevator on his way to the operating room and because of the delay a patient dies, he isn’t to blame for the patient’s death. However, suppose that one night, two people both drive home from a bar drunk. For one driver, the roads are clear and they get home safely. For the other, there are many cars on the road and after causing an accident someone dies. We want to say the second driver is more blameworthy than the first. The second driver killed someone, while the first driver did not. The common saying, “No harm, no foul” comes to mind. But wasn’t this difference just due to luck? If we don’t think luck plays a role in how blameworthy you are when something bad happens, then both drunk drivers are equally blameworthy. One driver got lucky and the roads were clear for him, but that wouldn’t make him any less blameworthy than the driver who was unlucky to have other cars on the road! What we ordinarily want to say here is that while both drivers did something wrong (they both put lives at risk), one is worse than the other (one actually killed someone). But this contradicts our ordinary belief that blame and wrongness doesn’t depend on luck. That’s why we don’t blame the doctor when he gets stuck somewhere and his patient dies. What we have here is conflicting ideas about wrongness and blame. Solving it, like with the possibility of selfless action, requires careful thought. Furthermore, if philosophers are able to clear this question up, it would have real practical consequences on our lives. Should we treat all drunk drivers as murderers regardless of if they hit anyone or not? Is the doctor to blame for the death of his patient, or does his bad luck excuse him from responsibility? If so, why would bad luck not also excuse a drunk driver who isn’t lucky enough to have empty streets on his drive home and as a result gets in an accident? Contrary to what the ordinary use of the term implies, philosophy is a professional field of inquiry that seeks to uncover facts about the world we live in. Often the questions professional philosophers struggle to answer are difficult ones and perhaps this is partly due to the fact that they are not of the sort that can be solved by empirical inquiry, but there is no reason to think they cannot be solved—some already have. We shouldn’t expect answers to all of the questions philosophers investigate during our lifetimes any more than we should expect chemistry, physics, or history to answer all of the questions they investigate during our lives. However, just like one might take a chemistry class and learn about that field’s present progress toward the correct theory of chemistry, one can take a philosophy class and come away with knowledge of what progress philosophers have made so far. 1.5 Exercises and Practice Problems 1. Explain the difference between the following activities: soccer, chemistry, mathematics, philosophy. 2. Explain Psychological Egoism and why it is a philosophical issue. 3. Explain why Psychological Egoism is false.