Analysis of Sustainable Development in Mountain areas

advertisement

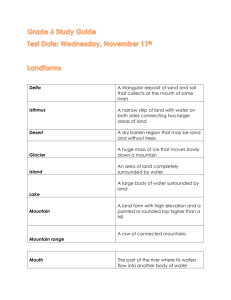

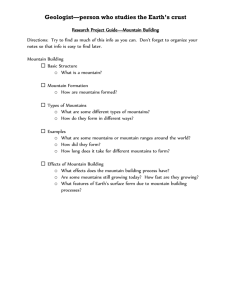

Analysis of Sustainable Development in Mountain areas by Daniel Buchbinder SSuussttaaiinnaabbllee D Deevveellooppm meenntt iinn M Moouunnttaaiinn AArreeaass Introduction This paper is intended to settle a basic background in the importance of mountain regions all over the globe. The intention is first, to understand the concept and importance of mountains, and understanding the most important variables that affect them; then to overview the reality of some regions, and finally to understand how it could be possible to make them sustainable. The approach from this paper will try to be form different angles or focuses; and the analysis will come when different mountain regions will be studied either from cultural, ethnic, ecological or economic views for example. One important fact to take in consideration that this year 2002 is the IYM (International Year of Mountains), so that a lot of the material in the present will be completely updated and fresh. Mountains are a vast storehouse of hydropower, timber, fuel wood, medicinal plants, minerals and water. Mountain biodiversity can be characterised at the scale of entire mountain systems, their component ranges, and individual peaks and valleys; each of these can be regarded as a more or less isolated 'ecological island' aidst the surrounding lowlands or on the inland margins of seascapes. Three types of biodiversity can be distinguished: genetic, species and ecosystem diversity. Biodiversity refers to the diversity of life on earth. It includes all species of plants, animals and microorganisms, their genetic material and the ecosystems in which they live. The many different forms of life have taken millennia to develop through a process of natural selection and evolutionary change. It is estimted that the number of species on earth may be as high as 15 million. Of this, only 1.7 million life forms are known to science, with thousands of species still waiting to be discovered and classified. To provide a global context for a discussion of mountain forests, it is first necessary to define their locations and types, and this in turn requires a definition of mountains or mountain areas. Altitude and slope and the environmental gradients they generate are key components of such a definition, but their combination is problematic. Simple altitude thresholds both exclude older and lower mountain systems and include areas of relatively high elevation that have little topographic relief and few environmental gradients. Using slope as a criterion on its own or in combination with altitude can resolve the latter problem but not the former. The statement of question for the present paper is as follows: With all the material including theoretical tools, articles and diverse literature, which is the perspective that should be used to approach to the sustainabilty in mountain areas, taking in consideration that all of them have completely different backgrounds and realities. The first stage of the analysis is to create a "theoretical" framework about mountains and different aspects that involve them, such as: Biodiversity, Climate, Social and Military conflicts, Forests, Gender and Water. This is with the intention of having a base for further analysis. 2 SSuussttaaiinnaabbllee D Deevveellooppm meenntt iinn M Moouunnttaaiinn AArreeaass Mountain biodiversity Mountains might seem like impenetrable monoliths of rock but, in reality, they are among the world's greatest sources of biodiversity, providing refuge to untold varieties of plants and animals. Many of these species have disappeared from lowland areas, crowded out by human activities. Many others exist nowhere else but on mountains. All people, wherever they live, share the responsibility of protecting mountain biodiversity. But it is mountain people who are the primary guardians of these irreplaceable global assets. Over generations, they have acquired a unique and detailed understanding of mountain ecosystems. Until now, governments and nternational organizations have largely overlooked the knowledge that mountain people possess and the important role that mountains play in preserving much of the world's biodiversity. Mountains have been described as islands of biodiversity surrounded by an ocean of monocultures and human-altered landscapes. Indeed, many plants and animals found in mountain habitat have disappeared from lowland regions, crowded out by human activities. Isolation and relative inaccessibility have helped protect and preserve species in mountains from deer, eagles and llamas to wild varieties of mustard, cardamom, gooseberry and pumpkin. In the Andes, for example, armers know of as many as 200 different varieties of indigenous potatoes. In the mountains of Nepal, they farm approximately 2 000 varieties of rice. On the top of a mountain in the Mexican Sierra de Manantlan, the only known stands of the most primitive wild relative of corn continue to grow. Mountain gorillas in central East Africa, spectacled bears in the Andes and resplendent quetzals in Central America are all clinging to ever-shrinking patches of cloud forest. At the same time, trade in rare mountain plants and animals, including species of orchids, birds and amphibians, continues to deplete populations. Poverty in mountain communities is one reason for habitat destruction. Commercial mining, logging, tourism and global climate change also exact a heavy toll on mountain biodiversity. Study case: The Andes, an array of biodiversity Of all the world's mountain ranges, tropical mountain environments are the greatest source of biodiversity. Of those, the eastern slopes of the Andes are believed to harbour the greatest amount of biological diversity. Tumbling down from peaks that sear Argentina, Bolivia, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru and Venezuela, the eastern slopes of the Andes possess a mind-boggling array of ecosystems from tropical rainforest, sub alpine forest, alpine heath and cloud forest to alpine grassland, tundra, snow and ice fields. Each of these zones, including the ice fields, has its own habitats and assemblages of plants and animals. Mountain people are the primary guardians of mountain bio-diversity. Over millennia, they have grown to understand the importance of shifting cultivation, of terraced fields, of recognizing plants with healing powers and of the sustainable harvesting of food, fodder and fuel wood from forests. Yet this extraordinary knowledge is often unappreciated or ignored by those outside of mountain communities. Far from the centres of commerce and power, mountain people have little influence over the policies that direct the courses of their lives and contribute to the degradation of their mountain homes. Indeed, up until now, mountain ecosystems and mountain people have received little attention at all from governments and organizations worldwide - a disparity that threatens not only mountain life but also the richness of lives everywhere. Not all mountain ecosystems are the same. Yet they all, whether in cloud forests, on alpine grasslands or along glacier-fed streams, have two things in common: altitude and diversity. Rapid changes in elevation, slope and orientation to the sun have a tremendous influence on 3 SSuussttaaiinnaabbllee D Deevveellooppm meenntt iinn M Moouunnttaaiinn AArreeaass temperature, wind, moisture availability and soil composition over very short distances. These subtle changes create pockets of life found nowhere else but at a particular elevation and on a specific mountain or range. Extreme climatic conditions push the limits of biological and human adaptation ever further. At high altitudes, native plants and animals develop special survival mechanisms. Some alpine wildflowers, for example, are adapted to live in the microhabitat created by the shade of a single rock. For the people who struggle to survive in these harsh environments, understanding and respecting this delicate balance is crucial. Farmers in the mountains of Burundi and Rwanda, for example, plant between 6 and 30 different varieties of beans in order to exploit subtle differences in elevation, climate and soil. Unique conditions, while generating a wide variety of species, make mountain ecosystems extremely fragile. Slight changes in temperature, rainfall or soil stability can result in the loss of entire communities of plants and anmals. Like island habitats, mountain ecosystems have no naturally evolved defences against invading species. Often, these alien invaders are introduced by human visitors or as a consequence of planting non-native crops or ornamental plants. Because they generally arrive without the predators or pests with which they evolved, these invasive species easily out compete native flora and fauna. Examples of some of the most damaging alien species include feral pigs in Hawaii in the United States and Costa Rica, goats in Venezuela, foreign grasses in Puerto Rico and alien trout in the United States' Yellowstone National Park. Methods to eradicate alien species are often experimental but always time-consuming and expensive. There has never been a "science" of mountains. Our understanding of mountains - as opposed to oceans or lowland rain forests - is derived from a variety of scientific disciplines that rarely exchange ideas or information. As a consequence, crucial relationships between upper and lower watersheds, mountain forests and alpine grasslands, mountain people and lowland urban dwellers have never been understood. Integrating the many ways in which we examine mountain ecosystems - blurring the lines between geology, meteorology, hydrology, biology, anthropology and economics - will not only raise awareness but aid the development of sustainable practices that will help protect mountain ecosystems and the biodiversity they shelter. Economic approach to the Mountain topic Mountain farmers cultivate thousands of plant varieties, many of which thrive only at specific elevations and climates. Often, they encourage cross-fertilization between wild and cultivated varieties. In the Himalaya, for example, domestic and wild varieties of lemon, orange and mango trees are grown side by side. In Mexico, farmers allow teosinte, a distant ancestor of maize, to grow near their cultivated maize. Planting many varieties of a single crop, as well as allowing wild varieties to mix in, encourages new characteristics to emerge while strengthening a species' genetic diversity and resilience. Many mountain farmers also say it improves yields and minimizes the need for pesticides, herbicides and fertilizers. Recently, however, a growing number of mountain farmers have felt pressured to abandon age-old practices for modern, high-yield farming techniques. These not only include planting fewer seed strains, relying more heavly on irrigation and higher doses of pesticides, herbicides and fertilizers, but choosing specific fruit and vegetable crops because they will generate higher returns in the market economy. While some communities may benefit financially, for others such changes spell enormous losses. A number of mountain communities, for example, have moved from traditional sheep and goat farming to cattle 4 SSuussttaaiinnaabbllee D Deevveellooppm meenntt iinn M Moouunnttaaiinn AArreeaass ranching. As a consequence, entire forest ecosystems have been wiped out as land has been cleared for crops and cattle. Climate change Human activities are profoundly affecting the world's climate, and mountains are a barometer of that effect. Each day, fossil fuel-burning technologies produce greenhouse gases that enhance the heat-trapping capability of the earth's atmosphere, gradually raising the planet's temperature. Because of their altitude, slope and orientation to the sun, mountain ecosystems are easily disrupted by variations in temperature. As the world heats up, mountain glaciers are melting at unprecedented rates, while rare plants and Animals struggle to survive over increasingly smaller ranges, and mountain people, already among the world's poorest citizens, face greater hardships. Understanding how climate change affects mountains is vital as governments and international organizations develop strategies to reverse current global warming trends. The roots of climate change Many things we do contribute to world climate change. Industrial processes and farming activities as well as unfettered enthusiasm for cars all generate gases that trap the sun's rays in the atmosphere. These gases, which include methane, nitrous oxide and especially carbon dioxide, enhance the "greenhouse" effect that naturally takes place in the environment. As the sun heats the earth's surface, the earth radiates energy back into space. Some of this outgoing energy is naturally trapped and absorbed by atmospheric greenhouse gases such as water vapour and carbon dioxide. Without this natural greenhouse effect, temperatures would be much lower and life, as we know it would not exist. Problems arise when atmospheric concentrations of greenhouse gases increase and more energy is trapped, keeping the earth's surface hotter than it would otherwise be. Some climate models predict that global temperatures will rise between 1 and 3.5°C by the year 2100. Although a few degrees might appear insignificant, an increase of this kind is far greater than any climate change experienced since the last ice age, 10 000 years ago. Among the consequences imagined, sea levels are expected to rise by 15 to 95 cm, causing flooding and untold damage to island nations and low-lying coastal communities. Already, the 11 000 residents of Tuvalu are being forced to abandon their island nation because of the rising sea level. Mountain Glaciers Mountain glaciers are melting at unprecedented rates. Over the last century, glaciers in the European Alps and the Caucasus Mountains have shrunk to half their size, while in Africa only 8 percent of Mount Kenya's largest glacier remains. If current trends continue, by the end of this century many of the world's mountain glaciers, including all those in Glacier National Park in the United States, will have vanished entirely. Changes in the depth of mountain glaciers and in their seasonal melting patterns will have an enormous impact on water resources in many parts of the world. In Peru, approximately 10 million residents of Lima depend on freshwater from the Quelcaya Glacier. In other parts of the world, rapid glacial melting is expected to disrupt agriculture and cause flooding. In Nepal, a glacial lake burst its banks in 1985, sending a 15 m wall of water rushing downhill, drowning people and destroying homes. Many climatologists believe that the decline in mountain glaciers is one of the first observable signs of human-induced global warming. 5 SSuussttaaiinnaabbllee D Deevveellooppm meenntt iinn M Moouunnttaaiinn AArreeaass The rarest species at risk Because of their shape and size, mountains support a wide range of climatic conditions. Climbing just 100 m up a mountain slope can offer as much climatic variety as travelling 100 km across flat terrain. Mountain climates are like narrow bands, each stacked on top of the other. Every rise in altitude generates different conditions, supporting unique and often isolated ecosystems with some of the world's greatest variety of plant and animal life. As the world heats up, however, conditions within each of these narrow bands is changing. Already scientists have witnessed examples of species moving uphill in search of more suitable habitat. Climatologists believe that a predicted rise in global temperatures of 3¼C would be equivalent to an ecological shift upwards of about 500 m in altitude. Not all species will be able to move. Those confined to the tops of mountains or below impassable barriers may face extinction as their habitat grows smaller. The rarest species are most at risk of extinction. Among these are mountain pygmy possum in Australia, ptarmigan and snow bunting in the United Kingdom, Gelada baboons in Ethiopia and monarch butterflies in Mexico. Climate change and mountain people For mountain people, each day atop the world's most extreme landscapes is a test of survival. Now, however, as global cliate change threatens to disrupt mountain environments, life for most mountain people will only get harder. For example, just as warming trends are forcing many species to migrate uphill in search of habitat, mountain people too will have to adapt to changes - or leave their homes as traditional sources of food and fuel grow scarce. At the same time, mountains will become more dangerous as melted permafrost and glacial runoff accelerate soil erosion as well as the likelihood of falling rocks, landslides, floods and avalanches. Irrigation will be affected, first by floods and then by drought, making survival harder for subsistence farmers as well as those who grow cash crops. Nearly all economic activities, such as logging and tourism, are likely to decline as mountain ecosystems are changed irrevocably. One of the indirect consequences of global warming in mountain regions is increasing risk of infectious diseases, where vulnerable people in these areas suffer the most. Monitoring mountains Mountains are a barometer of global climate change. These fragile ecosystems are highly sensitive to changes in temperature, and they are found on every continent. Indeed, many climatologists believe mountains provide an early glimpse of what may come to pass in lowland environments. For this reason, it is vital that the biological and physical components of mountains are strictly monitored and studied. Information on the health of mountain environments will undoubtedly assist governments and international organizations as they develop management strategies and mount strong campaigns to reverse current global warming trends. Political, social and military conflicts in mountain areas Peace is essential to sustainable development. Most wars and armed conflicts take place in the world's highlands. They represent perhaps the most significant barriers to sustainable development in mountains. In 1999, 23 of the 27 major armed conflicts in the world were being fought in mountain regions. 6 SSuussttaaiinnaabbllee D Deevveellooppm meenntt iinn M Moouunnttaaiinn AArreeaass Mountains: today's war zones Mountainous areas - ranging from Afghanistan to the Balkans, the Caucasus, the Andes, parts of the Near East and Africa - are the flash points of conflicts afflicting the world today. The reasons for this are complex and varied, but the effects on mountain people are universally devastating. Fighting prevents them from fundamental life-sustaining tasks ranging from collecting water to planting and harvesting crops. Where landmines are laid, agricultural lands must be left barren until expensive mine clearance can be undertaken, typically many years later. Infrastructure such as roads and schools are destroyed, halting economic development. The death, injuries and emotional trauma of war devastate individual lives and national advancement. Mountain regions suffer disproportionately from all these effects of conflict because they are often the poorest and least developed places in the world as well as the omelands of indigenous cultures. The remoteness of mountain regions can make it difficult to create a universally accepted set of rules and regulations regarding resource management - and their enforcement next to impossible. This creates oportunities for disputes over resources, territory and political jurisdiction. In the absence of a clearly defined and authoritative system for settling disputes, local conflicts can degenerate into long-standing conflicts between neighbouring communities and countries. Local clan affiliations may be the only systems isolated mountain communities feel they can trust to legitimately represent their interests. In these conditions, attempts to introduce new resource management practices that involve entire watersheds may be seen as a threat. Furthermore, in power vacuums, it is men who usually take control, often by force of arms. Women, even though they may have the deepest knowledge about how best to use local resources, are rarely consulted when conflicts arise over resource management. In 1995, the inability to manage mountain waters was the source of 14 international conflicts. A look at the global situation suggests that there are many opportunities for similar conflicts. Rivers rarely follow national borders - two or more countries share 214 river basins, covering more than half of the earth's surface and home to 40 percent of the world's population. As populations increase and the demand for water intensifies, the potential for international wars over water resources escalates. History offers some reasons for hope. There are many examples of international treaties regulating the use of mountain water that have stood the test of time, even though the countries involved have had intensely strained relations - such as India's and Pakistan's mutual respect for the treaty governing their shared use of the Indus River. For many communities in both highland and lowland areas, internal conflicts over the control of mountain waters are a far more real threat than international ones, and they can be just as catastrophic. National governments may be able to find comon interests in building a large dam but their shared interests may be at odds with those of the mountain communities that live near a proposed dam or in the lands that may be flooded. When local interests are not taken into account in planning large-scale water management projects, such as dams, there is bound to be protest. Legitimate protest is sometimes met with violent repression, triggering a downward spiral of conflict. Drugs: Conflict in Mountain areas Mountains are the primary battleground in international efforts to control the illegal drug trade. Both the coca bush, the leaves of which are used to produce cocaine, and the opium poppy, which is used to produce heroin, are native to mountain areas. For international criminal organizations, cocaine and heroin mean big money. For many mountain farmers in developing countries, with no other sources of income, the drug trade 7 SSuussttaaiinnaabbllee D Deevveellooppm meenntt iinn M Moouunnttaaiinn AArreeaass simply means survival. Often it is poor farmers who pay the heaviest price when governments and intenational organizations attempt to eliminate drug trafficking by curtailing the cultivation of illegal crops. When drug money is available to buy large amounts of sophisticated weaponry, conflicts over political, social or economic issues can explode into full-scale military and paramilitary operations. In these situations, it is the least affluent mountain families who suffer the most. Conflict in mountain areas often arises when mountain communities are denied a voice in how local resources are used. In some areas of the world, lack of effective political representation has been the fodder for violent revolution. Local rebel movements gain momentum when central governments based in lowland capitals impose their rule over mountain communities and decide how to eploit mountain resources and who will profit from them. When mountain communities are of indigenous heritage or belong to an ethnic, racial or religious minority, their marginalization can be politically expedient for governing parties. The exclusion of mountain people from national politics can also be the result of deeply engrained and unquestioned racist attitudes. Mountain forests Healthy mountain forests are crucial to the ecological health of the world. They protect watersheds that supply freshwater to more than half the world's people. They also harbour untold wildlife, provide food and fodder for mountain people and are important sources of timber and non-wood products. Yet in many parts of the world mountain forests are under threat as never before. Protecting these forests and making sure they are carefully managed is an important step towards sustainable mountain development. Deforestation, population growth and poverty In the last decade, tropical mountain forests have been disappearing at an astounding rate. Deforestation, while a complex phenomenon, is generally driven by population growth, uncertain land tenure, inequitable land distribution and the absence of strong and stable institutions. For example, in Southeast Asia and China, settlers escaping crowded lowland cities typically move "uphill", pushing upland farmers, whose land occupancy is already uncertain, higher into mountain forests. These new settlers, in turn, clear forests and threaten the livelihoods of mountain people. In the Andes and African highlands, the story is somewhat different but the root causes are much the same. After centuries of population growth and intensive land use, mountain forests have been reduced to small patches of green. In this case, the movement is reversed: mountain people flee "downhill", where they face even greater hardships as they struggle to survive on less productive lowlands. Some forestry and agricultural practices that are unsustainable contribute to deforestation by increasing hillside erosion, threatening mountain biodiversity and impairing the natural processes of forest ecosystems. Indeed, the destabilization of mountain forests creates an ever-escalating spiral of destruction. For example, when too many trees are cut, runoff and soil erosion increase at rates 20 to 40 times faster than soil can be stabilized, impairing water quality in streams and rivers and harming fish and other aquatic species. As more land is degraded, it increases the likelihood of natural hazards, such as avalanches, landslides and floods. Empowering mountain people Too often, policies and decisions concerning the management of mountain forests are made from afar, leaving those who live in mountain communities with the least amount of power and influence. This is one of the reasons that large numbers of mountain people live in 8 SSuussttaaiinnaabbllee D Deevveellooppm meenntt iinn M Moouunnttaaiinn AArreeaass poverty. According to the World Bank, one-quarter of the world's poor depend directly or indirectly on forests for their livelihood. Putting power back into the hands of mountain people is one important step towards alleviating their poverty and, in turn, protecting mountain forests. Measures that could accomplish these aims include reinvesting forest revenues in mountain communities and their resources, supporting community-based property rights, decentralizing power and accountability, building alliances and fostering a complementary middle ground between local knowledge and scientific understanding. Cloud forests - keeping their "heads" in the clouds Cloud foests are among the world's unique ecosystems. Bathed in fog and mist, they provide food and shelter to thousands of people as well as untold numbers of plants and animals. Yet, in as little as ten years time, the great majority of cloud forests may be gone Ð cleared for cattle grazing, logged and mined for resources and dried out by the effects of global warming and deforestation in lowland areas. As much as 90 percent of cloud forests in the northern Andes have already disappeared. Cloud forests are the result of persistent, seasonal or frequent wind-driven clouds that blow over mountain regions and provide forests with moisture well above normal rainfall. In some cases, this additional moisture can amount to nearly 20 percent of ordinary rainfall, or hundreds of millimetres of water. When cloud forests are cleared, the extra water extracted from the atmosphere is lost Ð along with the important functions that all forested headwaters play in maintaining water quality, stabilizing water flow and preventing hillside erosion. As recently as 30 years ago, cloud forests ranged over more than 50 million ha in narrow mountain belts. Found in tropical and subtropical parts of the world, they exist at heights of as low as 500 m and as high as 3 000 m above sea level. In 1999, a number of conservation organizations, including the United Nations Environment Programme, the World Conservation Union and the World Wide Fund for Nature, launched a programme to raise awareness and promote conservation of cloud forests. The last of the great coastal rain forests No other ecosystem on earth produces as much living matter as the world's coastal temperae rain forests. Found in wet, cool climates where marine air collides with coastal mountains and generates large amounts of rainfall, these giant forests create as much as 500 to 2000 tonnes of wood, foliage, leaf litter, moss, plant life and soil per hectare. But far from wasteful, this immense organic output prouces food and shelter for countless species of insects, reptiles, birds and mammals and also contributes directly to the health of ocean life nearby. These distinct forest ecosystems have been depleted and, in many cases, completely destroyed by farming, urban development and unsustainable harvesting practices. Once found on five continents, coastal rain forests survive only on two. Today only about 30 to 40 million ha of coastal temperate rain forest remain, mostly along 8 000 km of coastline in Chile and the Pacific Northwest of North America. Of the world's remaining coastal temperate rain forests, only 16 percent are protected. Over two-thirds of the protected area is in Alaska. Mountain forests for the future As mountain forests and all the life they harbour continue to vanish in many parts of the world, it is more important than ever for governments to find a balance between productive uses of forests and their protection. To this end, one important step would be to recognize and support mountain people in their role as the primary guardian of mountain forests. Too often in the global market economy, 9 SSuussttaaiinnaabbllee D Deevveellooppm meenntt iinn M Moouunnttaaiinn AArreeaass the most widely accepted thing of value in a forest is timber. In mountain communities, timber is often less important than the ecosystem that produces water for drinking and irrigation, and plants and animals for food, fodder and medicines. Mountain people see the forest and not just the trees. Like everyone, they depend on the entire forest ecosystem for their survival. Mountain forest policies should acknowledge the needs of local communities first, before taking into consideration the interests of other parties, such as the commercial forestry and tourism sectors. Mountain forests stretch over 9 million square kilometres, representing 28 percent of the world's closed forest area. Almost 4 million square kilometres of mountain forests are found above 1 000 metres Gender issues in mountain areas Inaccessibility is perhaps the greatest influence shaping the lives of mountain inhabitants. And while mountain women face many of the same challenges as women throughout the developing world, the work of women in mountain regions is intensified by altitude, steep terrain and isolation. Women are vital to the sustainability of mountain communities and play a prominent role in agricultural production, resource management and the household. Yet little information exists about the status of women and gender relations in mountain regions. Studies about women typically focus on those in lowland and urban environments, and are absent from most economic and social histories of mountain regions, which are largely written by men. It is impossible to describe gender relations in all mountain areas. Every region has its own distinct cultural and environmental characteristics. This text relies on extensive research in the Hindu Kush-Himalaya. The status of mountain women Many women in mountain regions have more freedom of movement, independence in decision-making and higher status than women in lowland areas. This may be due to less rigid religious beliefs, such as those found in indigenous systems, and because of their vital contribution in eking out a living in a harsh mountain environment. But this higher status is at risk. Whereas inaccessibility has helped to preserve many languages and cultural traditions in mountain regions, mainstream pressures to adopt national cultures now threaten to undermine the central role of women by relegating them to the home and to domestic chores. Division of labour Women carry a heavier workload than men in mountain regions. While women share agricultural and livestock tasks fairly evenly with men, they also collect water, fuel wood and fodder as well as process food, cook, and care for children. But the workload of mountain women is intensified by a number of factors in mountainous regions, including a limited access to resources, an out migration of men who seek work in lowland areas and environmental degradation. In most cases, mountain women also lack economic independence and have only limited access to health care and education. The survival of mountain communities requires the absence of men for trading and herding purposes. During these periods, women maintain the farm and household and participate in small trade and income-earning activities. Increasingly, however, the outmigration of men to lowland and urban centres for cash wages leaves women as heads of the household for long periods with only limited access to credit, agricultural extension, and other services. 10 SSuussttaaiinnaabbllee D Deevveellooppm meenntt iinn M Moouunnttaaiinn AArreeaass Women seldom hold ownership and tenure rights to land, trees, water and other natural resources. While women contribute most of the labour for agriculture, they rarely have formal control of land or ownership of animals. Mountain women's lack of control over productive resources means they cannot raise collateral for bank loans, and hampers efforts to improve or expand their farm activities and earn cash incomes. Traditionally, most extension services have been devoted to farmers who own land and who are able to obtain credit and invest it in inputs and technological innovations. Since women often lack access to land or other collateral, extension services bypass women. This marginalizes the role of women in agricultural production systems by emphasizing highyielding crop varieties to which women have little access. This also undermines the traditional knowledge women possess about agriculture and resource management. Women are forced to travel greater distances to collect fuel and fodder as a result of diminishing forestry resources and a declining agricultural base. Environmental degradation in mountain regions also increases the erosion of topsoil, leading to crop failure. The result is growing outmigration, food deficits and incidences of trafficking of mountain women into lowland and urban centres. Gender, public services and politics While the numer of girls attending school in mountain areas is increasing, their enrolment is considerably lower than of boys. But the enrolment of girls in school does not guarantee their attendance. Frequently, the girls’ mothers, who reqire their help for childcare and domestic chores, are forced to take them out of school. Health remains a neglected issue in mountain development. While hospitals are accessible in some areas, mountain women generally have less access to medical care, family planning or female doctors. In the cold climate of high altitude regions, the body metabolises food faster, so people need higher-calorie diets. Since females often have less access to household resources, women and girls are at greater risk of hunger and poor nutrition. Most mountain communities lack acess to adequate water supplies and proper sanitation facilities, raising the risk of sanitation-related illness. Women, as the primary water carriers and users are in constant contact with polluted water, increasing their vulnerability. Throughout the developing world, women are prevented from full participation in politics because of their lack of education in addition to their heavy workload. However, the number of women voting and taking up community leadership roles in mountain regions is increasing. Many women in mountain regions lack self-confidence and feel less important than men. Factors that influence the self-esteem of mountain women include culture, education, interaction with others outside the community and the ability to earn an income, among others. n Tibet, where women are commonly described as free spirited and strong willed, women have a lower self-image of themselves than do men. While government interventions to help rural women are found in many mountain areas, there are significant gaps between the policy goals and local realities. Policies designed outside the community are inappropriate for the local context and many ignore the daily activities of men and women. Sometimes women are too busy to take advantage of health and education services. Frequently, policy directives come without funds, so they become little more than expressions of intent noted on official documents. Mountain waters Mountains are often called nature's water towers. Because of their size and shape, they intercept air circulating around the globe and force it upwards where it condenses into clouds, which provide rain and snow. All the major rivers in the world - from the Rio Grande to the Nile - have their headwaters in mountains. As a consequence, more than half the world's people rely on mountain water to grow food, to produce electricity, to sustain 11 SSuussttaaiinnaabbllee D Deevveellooppm meenntt iinn M Moouunnttaaiinn AArreeaass industries and, most importantly, to drink. As populations increase and demand for clean water grows, the potential for conflict also rises. Careful management of mountain ecosystems and the water resoures they support has never been more important to our longterm security and survival. Each day, one of every two people on the planet quenches his or her thirst with water that originates in mountains. One billion Chinese, Indians and Bangladeshis, 250 million people in Africa, and the entire population of California, United States, are among the 3 billion people who rely on the continuous flow of fresh, clean mountain water. Yet the future of this vital, life-giving resource has never been more uncertain. Deforestation of mountain mining, agriculture, urban sprawl and global warming are all taking their toll on mountain watersheds. At the same time, the worldwide demand for freshwater continues to soar unabated. For example, while the number of people on the planet has doubled over the last cenury, the demand for freshwater has jumped six fold. If current trends continue, by 2050 as many as 4.2 billion people will be living in countries that cannot meet the daily minimum requirement of 50 litres of water per person, according to a recent report by the United Nations Population Fund. Already, 2.3 billion people worldwide endure chronic water shortages. A disproportionate number live in developing countries where water scarcities are so great that the ability to grow food and to build a stable economy have been severely hindered. The fragility of mountain terrain Words such as "stability," "strength" and "endurance" are often used as metaphors for mountains but, in reality, mountains can be fragile. The vertical nature of a mountain - its contours, projections, peaks and plateaus - makes its surface highly unstable. In fact, mountain soils, which form more slowly because of the higher altitudes and colder temperatures, are often young, shallow and poorly anchored. Add the threat of earthquakes as well as the pull of gravity, and it is not surprising that mountains are susceptible to soil erosion. Yet human activities also contribute to the fragility of mountain terrain. Unsustainable forestry and inappropriate farming practices, for example, can lead to deforestation and a severe loss of vegetative grondcover. Without trees and plant life to absorb water, runoff increases and soil erosion escalates. A doubling of water speed, for example, produces an eight- to sixteen fold increase in the size of particles that can be transported. Eventually, as more and more soil and sediment travels downwards, the likelihood of avalanches, landslides and floods increases. Moving mountains to supply mega cities Between 1950 and 1990, the number of cities with populations greater than 1 million increased from 78 to 290. Some of these places, particularly in the developing world, have exploded into "megacities" with millions of people and unprecedented demands for freshwater and electricity. To help meet the needs of growing cities, many countries are developing schemes to divert mountain rivers or dam them entirely. The Tucurui Dam in Brazil, for example, generates electricity for cities and industries in the country's north by diverting the Tocantins River, an Amazon tributary. At the same time, one of the Tehri Dam's functions in the Indian Himalaya will be to supply freshwater to the Indian city of Delhi, 250 km away. As with all large-scale initiatives like these, the potential is great but the threat to mountain watersheds, people and biodiversity is even greater. Protecting mountain ecosystems and the freshwater they generate should be the first priority as nations consider such development plans. 12 SSuussttaaiinnaabbllee D Deevveellooppm meenntt iinn M Moouunnttaaiinn AArreeaass Case in point The Aral Sea Basin: overuse of mountain water resources The degradation of the Aral Sea, which flows into both Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, represents one of the greatest environmental catastrophes in human history. In 1985, water from the Tien Shan and the Pamir mountains was rerouted to fields in a failed irrigation experiment. As a result, the Aral Sea shrunk to half its size, leaving 266 invertebrates, 24 fish species and 94 plant species extinct. Analysis and Discussion After this overview of the most important variables that affect sustainability of mountain regions and understanding the great importance they hake for millions of people directly and indirectly there are core ideas to be discussed and analysed: Government, private institutions and civil society roles These are the players who can change the destiny of mountains around the world. Based on some readings from the World Development Report 2001, we can understand that without a effort and integration of these parties, a prosperous future for mountains will be in the fragile line. In this globalized world private institutions such as multinationals will have to take in consideration several factors to develop their businesses abroad, obviously limited by local governments, but with the special and crucial participation and observation of civil society. A very sensitive topic is the NGO's participation in this issue; which or where is the restriction for their activities and plans? The core issue here is where to draw the border for each of these players and how to create a balance or equilibrium, in order to establish the best policies and regulations for mountain welfare. International research and aid As we have seen, problems and issues are not independent and they can either start vicious or virtuous circles; so they should be seen as a whole and not as spared topics. A good way to solve some of the problems would be to create interdisciplinary groups to review all sort of issues regarding mountain development. Why groups already existing are not using extreme measures to combat some of the problems, do they have natural, social or government. constraints. Which would be the institutions to support this programs and how would they apply them, the UN for example?, or maybe smaller but more commited institutions. As mentioned before the present year 2002, is the International Year of Mountains, that is a great idea, there is a summit in October; Is that enough??? Problems to solve, challenges and opportunities to capture Virtually all issues regarding mountains have been reviewed in previous sections; is for understanding that there are a lot of increasing problems, but there is this great option, that most of this problems can turn around and become enormous opportunities for everyone, for mountain inhabitans, for all the people who is affected directly or indirectly by mountains (that would be everyone in this planet) and specially for the conservation and welfare of nature, 13 SSuussttaaiinnaabbllee D Deevveellooppm meenntt iinn M Moouunnttaaiinn AArreeaass meaning all species that are in danger of extintion, and in general all biodiversity that has been poluted and dramatically changed by the hand of men. How as this paper linked to class topics? Starting with the idea that the paper is about sustainability in the mountains, almost every aspect of the paper could be related to lectures we have had. Some data form the page of the World bank was very usefull for the elaboration of this project and it was also important for the guidance of different lectures. The main topics form the paper are some of the important topics of the lectures such as poverty, sustainability in indigenous areas, developing countries, sustainable tourism, climate change on earth and some more. As it was mentioned before, this paper was thought because of the reading Sustainability in the Himalaya region. Conclusions In a certain way the previous section could be seen as a conclusion, because a conclusion for a paper like this can not be any concrete proposal or even less a critique of the situation. It was intended to be a specific (maybee not very deep) research paper on the basic variants in the topic. So many issues can come to our minds when we notice how essential mountains are for us in our present but specially for our own future and next generations (following the sustainable development definition). It is not necessary to dramatize the situation but the urgent need for changing the dynamics of our behavior is obvious. During the creation of this paper, a lot of lectures, articles and concpets reviwed in lectures were applied in order to create links between different topics and to bring some theoretical issues into a pragmatic approach. Therefore the main intention of this study is not to create or develop a sense of romantic idea that would not be useful at all, but to transmit the huge value of mountin areas and even more, the greater importance to think further in the topic and options that could make mountains viable regions, which are less and less by the way. 14 SSuussttaaiinnaabbllee D Deevveellooppm meenntt iinn M Moouunnttaaiinn AArreeaass Bilbiography Himawanti - Women of the Hindu Kush-Himalayas Anupam Bhatia (ed) December 2001 Mountains forever Kathmandu: ICIMOD, Helvetas, Spiny Babbler December 2001 *Perez, Baltazar- Montanas: Opcion Viable para el Futuro (Mountains: viable option for the future), , 1999 Univesidad Nacional Autonoma de Mexico *Jimenez, Guindilla, Pena – Rios, Mares y Montanas, Sustentables?? (Rivers, Seas and Mountains, Sustainable??) Ed. Planeta 2000 (pp 120-158, 173-205) Articles State of mountain agriculture in the Hindu Kush-Himalayas: A Regioanl Comparative Analysis Gorwth, poverty alleviation and sustainable resource management in the mountain areas of south Asia. * These books were used from sources of latin american researchers and form the UNAM the national university in Mexico 15