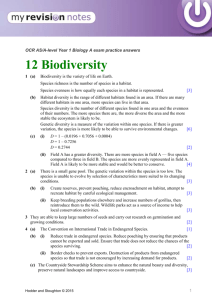

Implementation of the Biodiversity Convention in Europe

advertisement