The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism

advertisement

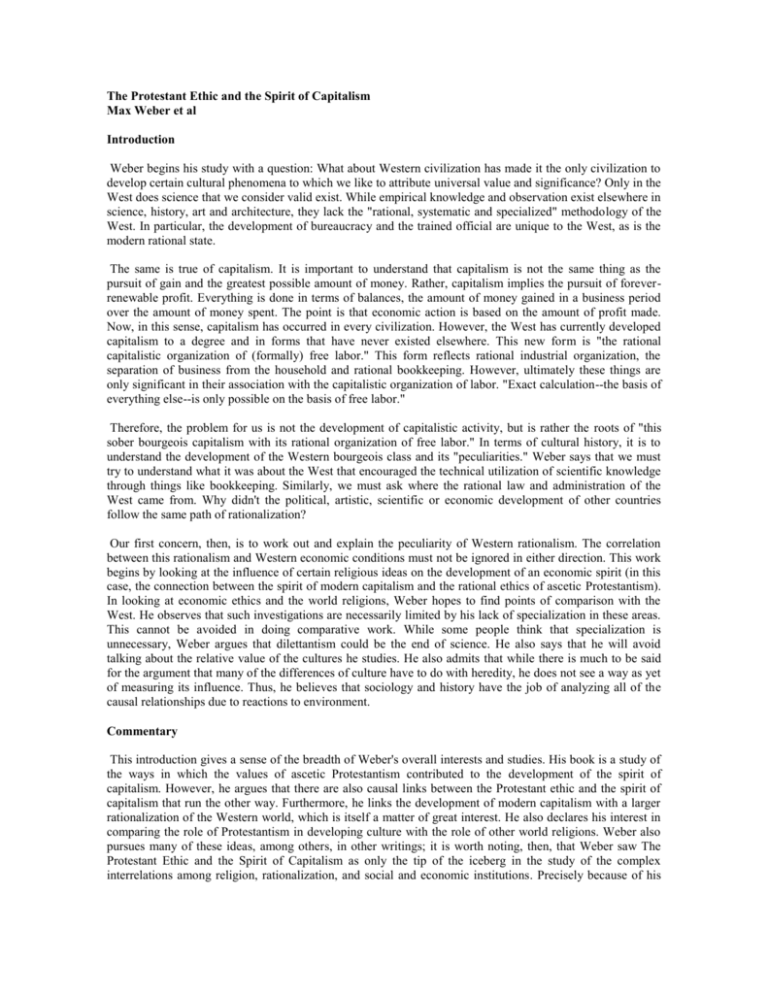

The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism Max Weber et al Introduction Weber begins his study with a question: What about Western civilization has made it the only civilization to develop certain cultural phenomena to which we like to attribute universal value and significance? Only in the West does science that we consider valid exist. While empirical knowledge and observation exist elsewhere in science, history, art and architecture, they lack the "rational, systematic and specialized" methodology of the West. In particular, the development of bureaucracy and the trained official are unique to the West, as is the modern rational state. The same is true of capitalism. It is important to understand that capitalism is not the same thing as the pursuit of gain and the greatest possible amount of money. Rather, capitalism implies the pursuit of foreverrenewable profit. Everything is done in terms of balances, the amount of money gained in a business period over the amount of money spent. The point is that economic action is based on the amount of profit made. Now, in this sense, capitalism has occurred in every civilization. However, the West has currently developed capitalism to a degree and in forms that have never existed elsewhere. This new form is "the rational capitalistic organization of (formally) free labor." This form reflects rational industrial organization, the separation of business from the household and rational bookkeeping. However, ultimately these things are only significant in their association with the capitalistic organization of labor. "Exact calculation--the basis of everything else--is only possible on the basis of free labor." Therefore, the problem for us is not the development of capitalistic activity, but is rather the roots of "this sober bourgeois capitalism with its rational organization of free labor." In terms of cultural history, it is to understand the development of the Western bourgeois class and its "peculiarities." Weber says that we must try to understand what it was about the West that encouraged the technical utilization of scientific knowledge through things like bookkeeping. Similarly, we must ask where the rational law and administration of the West came from. Why didn't the political, artistic, scientific or economic development of other countries follow the same path of rationalization? Our first concern, then, is to work out and explain the peculiarity of Western rationalism. The correlation between this rationalism and Western economic conditions must not be ignored in either direction. This work begins by looking at the influence of certain religious ideas on the development of an economic spirit (in this case, the connection between the spirit of modern capitalism and the rational ethics of ascetic Protestantism). In looking at economic ethics and the world religions, Weber hopes to find points of comparison with the West. He observes that such investigations are necessarily limited by his lack of specialization in these areas. This cannot be avoided in doing comparative work. While some people think that specialization is unnecessary, Weber argues that dilettantism could be the end of science. He also says that he will avoid talking about the relative value of the cultures he studies. He also admits that while there is much to be said for the argument that many of the differences of culture have to do with heredity, he does not see a way as yet of measuring its influence. Thus, he believes that sociology and history have the job of analyzing all of the causal relationships due to reactions to environment. Commentary This introduction gives a sense of the breadth of Weber's overall interests and studies. His book is a study of the ways in which the values of ascetic Protestantism contributed to the development of the spirit of capitalism. However, he argues that there are also causal links between the Protestant ethic and the spirit of capitalism that run the other way. Furthermore, he links the development of modern capitalism with a larger rationalization of the Western world, which is itself a matter of great interest. He also declares his interest in comparing the role of Protestantism in developing culture with the role of other world religions. Weber also pursues many of these ideas, among others, in other writings; it is worth noting, then, that Weber saw The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism as only the tip of the iceberg in the study of the complex interrelations among religion, rationalization, and social and economic institutions. Precisely because of his understanding of this complexity, his conclusions are typically cautious and limited in scope. He encourages a flexible method of analysis, which uses different perspectives in order to gain a fuller picture of social reality. This introduction also suggests a bit about Weber's approach to sociology. He is analyzing unique formulations of social institutions, looking at the ways in which certain contingent ideas affected the development of capitalism. Thus, he assumes that all societies are on different paths. He does not believe in one universal path of progress that all civilizations are currently on, but rather argues for the particularity of culture. This is quite different from many of the popular theories of his time. For example, according to Marxism, history is on an inevitable path, and the development of capitalism was not culturally contingent. Weber rejects such universalism, and sees the Western experience as due to specific cultural developments. Chapter 1 - Religious Affiliation and Social Stratification Weber observes that according to the occupational statistics of countries of mixed religious composition, business leaders and owners, as well as the higher skilled laborers and personnel, are overwhelmingly Protestant. This fact crosses lines of nationality. Weber observes that this could be partly explained by historical circumstances, such as the fact that richer districts tended to convert to Protestantism. This, however, leads to the question of why, during the Protestant Reformation, the districts that were most economically developed were also most favorable to a revolution. It is true that freedom from economic traditions might make one more likely to also doubt religious traditions. However, the Reformation did not eliminate the influence of the Church, but rather substituted one influence for another that was more penetrating in practice. Weber also says that though it might be thought that the greater participation of Protestants in capitalism is due to their greater inherited wealth, this does not explain all the phenomena. For example, Catholic and Protestant parents tend to give their children different kinds of education, and Catholics have more of a tendency than Protestants to stay in handicrafts rather than to go into industry. This suggests that their environment has determined the choice of occupation. This seems all the more likely because one would normally expect Catholics to get involved in economic activity in places like Germany, because they are excluded from political influence. However, in reality Protestants have shown a much stronger tendency to develop economic rationalism than Catholics have. Our task is to investigate the religions and see what might have caused this behavior. One explanation that has been given is that the Catholics are more "otherworldly" and ascetic than the Protestants, and are therefore indifferent to material gain. However, this does not fit the facts of today or of the past, and such generalities are not useful. Furthermore, Weber argues that there might actually be an "intimate relationship" between capitalist acquisition and otherworldliness, piety, and asceticism. For example, it is striking that many of the most ardent Christians come from commercial circles, and there is often a connection between otherworldly religious faith and commercial success. However, not all Protestant circles have had an equally strong influence, with Calvinism having a stronger force than Lutheranism. Thus, if there is any relationship between the ascetic Protestant ethic and the spirit of capitalism, it will have to be found in purely religious characteristics. In order to understand the many potential relationships here, it is necessary to try to understand the characteristics of and differences among the religious thoughts of Christianity. It is first necessary, though, to speak about the phenomenon we wish to understand and the degree to which an explanation is even possible. Commentary Throughout his essay, Weber will be making both empirical and theoretical arguments. It is therefore important to understand the differences and connections between the two kinds of arguments. An empirical argument is based on observation or experiment; it describes facts that can be proven. For example, Weber's claim that Protestants are more involved than Catholics in capitalistic activities is an empirical argument, based on his observations in Germany and elsewhere. Other studies might question the validity of such a claim, and in fact Weber has been criticized for many of the empirical arguments that underlie his study. Theoretical arguments are more speculative; their purpose is to give meaning to empirical observations. For example, Weber notices a correlation between ascetic Protestantism and the spirit of capitalism. What could explain such a connection? It is not possible to simply run an experiment or do a statistical study; this might show correlations, but it will not tell a causal story. Thus, Weber explores more about the "spirit" of capitalism, and about ascetic Protestantism, hopefully getting an accurate description of each (this is empirical work). He then attempts to tell a coherent story about what happened, given the information available (this is theoretical). He looks at his information through the lens of his theory, and ideally his theory would account for all of the relevant facts available. In reality, the world is far too complex for any theory to possible capture all of its intricacies, and Weber himself is very cautious about the limited ability of any theory to explain the world. However, theory is still useful, since it is the only way to give empirical facts any broader meaning. Weber's study has important implications for how we look at religion. Weber does not simply take religion on its own terms, seeing what it means to its founders and followers. For Weber, religion also has another function. It can create broader social values and be instrumental in the creation of social institutions completely unrelated to its own goals and ends. Religion has a generative power, and the influence of its ideas should be studied in areas seemingly unrelated to its theological principles, such as the creation of economic institutions. Chapter 2 - The Spirit of Capitalism What does the term "the spirit of capitalism" mean? This term can only be applied to something that is "a complex of elements associated in historical reality which we unite into a conceptual whole from the standpoint of their cultural significance." The final concept can only come out at the end of an investigation into its nature. There are many ways to conceptualize the spirit of capitalism. We must work out the best formulation based on what about that spirit interests us; this, however, is not the only possible point of view. To come up with a formulation, Weber presents a long excerpt from the writings of Benjamin Franklin. He says that Franklin's attitudes illustrate capitalism's ethos. Franklin writes that time is money, that credit is money, and that money can beget money. He encourages people to pay all of their debts on time, because it encourages the confidence of others. He also encourages people to present themselves as industrious and trustworthy at all times. Weber says that this "philosophy of avarice" sees increasing capital as an end in itself. It is an ethic, and the individual is seen as having a duty to prosper. This is the spirit of modern capitalism. While capitalism existed in places like China and India, and in the Middle Ages, it did not have this spirit. All of Franklin's moral beliefs relate to their usefulness in promoting profit. They are virtues for this reason, and Franklin does not object to substitutes for these virtues that accomplish the same ends. However, this is not simply egocentrism. The capitalist ethic does not embrace a hedonistic life-style. Earning more and more money is seen completely as an end in itself, and is not simply the means for purchasing other goods. This seemingly irrational attitude towards money is a leading principle of capitalism, and it expresses a type of feeling closely associated with certain religious ideas. Earning money reflects virtue and proficiency in a calling. This idea of one's duty in a calling is the basis of the capitalist ethic. It's an obligation that the individual should and does feel toward his professional activity. Now, this does not mean that this idea has only appeared under capitalistic conditions, or that this ethic must continue in order for capitalism to continue. Capitalism is a vast system that forces the individual to play by its rules, in a kind of economic survival of the fittest. However, Weber argues that in order for a manner of life so conducive to capitalism to become dominant, it had to originate somewhere, as a way of life common to a large number of people. It is this origin that must be explained. He rejects the idea that this ethic originated as a reflection or superstructure of economic situations. In Massachusetts, the spirit of capitalism was present before the capitalistic order took shape, as complaints of profit-seeking emerged as early as 1632. Furthermore, the capitalistic spirit took stronger hold in places like Massachusetts that were founded with religious motives than in the American South, which was settled for business motives. Furthermore, the spirit of capitalism actually had to fight its way to dominance against hostile forces. In ancient times and during the Middle Ages, Franklin's attitude would have been denounced as greed. It is not the case that greed was less pronounced then, or in other places that lack the capitalist ethic. The biggest opponent the capitalist ethic has had in gaining dominance has been traditionalism. Weber says that he will try to make a provisional definition of "traditionalism" by looking at a few cases. First, there is the laborer. One way in which the modern employer encourages work is through piece-rates, for example paying an agricultural worker by the amount harvested. In order to increase productivity, the employer raises the rate of pay. However, a frequent problem is that rather than work harder, the workers actually work less when pay increases. They do this because they can reduce their workload and still make the same amount of money. "He did not ask: how much can I earn in a day if I do as much work as possible? but: how much must I work in order to earn the wage, 2 1/2 marks, which I earned before and which takes care of my traditional needs?" This reflects traditionalism, and shows that "by nature" man simply wants to live as he is used to living, and earn as much as is necessary to do this. This is the leading trait of pre-capitalistic labor, and we still encounter this among more backward peoples. Weber then addresses the opposite policy, of reducing wages to increase productivity. He says that this effectiveness of this has its limits, as wages can become insufficient for life. To be effective for capitalism, labor must be performed as an end in itself. This requires education, and is not simply natural. Weber then considers the entrepreneur in terms of the meaning of traditionalism. He observes that capitalistic enterprises can still have a traditionalistic character. The spirit of modern capitalism implies an attitude of rational and systematic pursuit of profit. Such an attitude finds its most suitable expression through capitalism, and has most effectively motivated capitalistic activities. However, the spirit of capitalism and capitalistic activities can occur separately. For example, consider the "putting-out system." This represented a rational capitalistic organization, but it was still traditional in spirit. It reflected a traditional way of life, a traditional relationship with labor, and traditional interactions with customers. At some point, this traditionalism was shattered, but not by changes in organization. Rather, some young man went into the country, carefully chose weavers whom he closely supervised, and made them into laborers. He also changed his relationship with his customers by making it more personal and eliminating the middleman, and he introduced the idea of low prices and large turnover. Those who could not compete went out of business. A leisurely attitude towards life was replaced by frugality. Most importantly, it was usually not new money that brought about this change, but a new spirit. Those people who succeeded were typically temperate and reliable, and completely devoted to their business. Today, there is little connection between religious beliefs and such conduct, and if it exists it is usually negative. For these people, business is an end in itself. This is their motivation, despite the fact that this is irrational from the perspective of personal happiness. In our modern individualistic world, this spirit of capitalism might be understandable simply as adaptation, because it is so well suited to capitalism. It no longer needs the force of religious conviction because it is so necessary. However, this is the case because modern capitalism has become so powerful. It may have needed religion in order to overthrow the old economic system; this is what we need to investigate. It is hardly necessary to prove that the idea of moneymaking as a calling was not believed for whole epochs, and that capitalism was at best tolerated. It is nonsense to say that the ethic of capitalism simply reflected material conditions. Rather, it is necessary to understand the background of ideas that made people feel they had a calling to make money. Commentary Many commentators on capitalism tend to assume or argue that its existence is inevitable, that it is fundamental to human nature, or reflects an important step in a universal series of stages. Weber's account brings such claims into question. According to Weber, the "spirit" necessary for successful capitalistic activities is not natural. Striving for profit is not the only way to approach economic activities; one could, for example, simply strive for subsistence or a traditional way of life. According to Weber, when capitalism does prosper, it does so because people have embraced and internalized certain values. These values, and not just human nature, make capitalism possible. Capitalism cannot then simply be a necessary step in the world's development, because in order for it to emerge, particular values must be present. Weber thus leaves space for the importance of ideas and culture in the history of human development. He is also specifically replying to one approach to sociology and history, promulgated by many Marxists and often called "materialism." This approach sees all ideas and developments, including the spirit of capitalism, as a reflection or superstructure of economic situations. Economic interactions are the basis for all social institutions. Religion itself is a product of such interactions; it cannot be a driving force of history. Weber's point is that for Western civilization to ever emerge out of feudal traditionalism, it needed to embrace a new set of values. These values couldn't simply have emerged out of the economic situation; we needed these values in order to rid ourselves of that situation. The formation of the values was influenced by economic situations, but not completely caused by them. According to Weber then, the materialist view is overly simplistic and not supported by the facts. Any complete understanding of historical progress would include a multiplicity of causes, and appreciate that the causal relationship between economic situations and religious outlooks goes both ways. It is also important to notice the ways in which Weber attempts to define concepts like traditionalism and the "spirit" of capitalism. Weber relies heavily on anecdotes and case studies in order to give a sense for what these terms might mean; his discussion of the spirit of capitalism relies extremely heavily on the writings of Benjamin Franklin. This approach has both positive and negative attributes. His examples are carefully chosen and give a good grounding to his definition. However, because they are simply examples, they can potentially be attacked as not representative of a larger ethos. Weber's characterizations have indeed been attacked by some, and he has been criticized for not relying on more quantitative surveys. Chapter 3 - Luther's Conception of the Calling. Task of the Investigation. Weber begins this chapter by looking at the word "calling." Both the German word "Beruf" and the English word "calling" have a religious connotation of a task set by God. This type of word has existed for all Protestant peoples, but not for Catholics or in antiquity. Like the word itself, the idea of a calling is new; it is a product of the Reformation. Its newness comes in giving worldly activity a religious significance. People have a duty to fulfill the obligations imposed upon them by their position in the world. Martin Luther developed this idea; each legitimate calling has the same worth to God. This "moral justification of worldly activity" was one of the most important contributions of the Reformation, and particularly of Luther's role in it. However, it cannot be said that Luther actually had the spirit of capitalism. The way in which the idea of worldly labor in a calling would evolve depended on the evolution of different Protestant churches. The Bible itself suggested a traditionalistic interpretation, and Luther himself was a traditionalist. He came to believe in absolute obedience to God's will, and acceptance of the way things are. Thus, Weber concludes that the simple idea of the calling in Lutheranism is at best of limited importance to his study. This does not mean that Lutheranism had no practical significance for the development of the capitalistic spirit. Rather, it means that this development cannot be directly derived from Luther's attitude toward worldly activity. We should then look to a branch of Protestantism that has a clearer connection--Calvinism. Thus, Weber makes his starting point the investigation of the relationship between the spirit of capitalism and the ascetic ethic of the Calvinists and other Puritans. The capitalistic spirit was not the goal of these religious reformers; their cultural impact was unforeseen and maybe undesired. The following study will hopefully contribute to the understanding of how ideas become effective forces in history. Weber then adds a few remarks to avoid any confusion about his study. He is not trying to evaluate the ideas of the Reformation in either social or religious worth. He is only trying to understand how certain characteristics of modern culture can be traced to the Reformation. We shouldn't try to see the Reformation as a historically necessary result of economic factors. Many historical and political circumstances, fully independent of economic law, had to occur in order for the Churches to even be able to survive. However, we should also not be so foolish as to argue that the spirit of capitalism could only have occurred as the result of particular effects of the Reformation, and that capitalism is therefore a result of the Reformation. Weber's goals are more modest. He wants to understand whether and to what degree religious forces have helped form and expand the spirit of capitalism, and what aspects of our culture can be traced to them. He will examine when and where there are correlations between religious beliefs and practical ethics, and clarify how religious movements have influenced material culture's development. Only when this has been determined can we try to estimate the degree to which the historical development of modern culture can be attributed to those religious forces, and to what extent to other forces. Commentary This chapter is the final stage of Weber's presentation of the "problem" of the potential connection between the Protestant ethic and the spirit of capitalism. It is illustrative of Weber's method that presenting the problem takes him three chapters of writing. Once again, in this chapter Weber spends significant time telling us what he will not be studying, and how limited his examination really is. Consider the significance of this approach, both as a methodological and rhetorical tool. Does such caution add to or detract from his writing? Weber also introduces the idea of a "calling" to worldly activity. This will be an important concept when Weber develops his theory in later chapters. Notice first that Weber does not think that belief in a calling is sufficient to explain the spirit of capitalism. A calling can be consistent with traditionalism, since it can imply that a person should accept his role in life and not strive for more. However, it could also potentially support a more capitalistic ethic. According to Weber, before the Reformation, people did not see their "worldly" activities (such as their occupations and businesses) as being in service to God. Rather, worldly activities were perceived more like necessary evils. The monastic lifestyle, where people removed themselves from the world in order to contemplate God, was glorified. The Reformation rejected this attitude. It was seen as wrong to remove yourself from the world; serving God meant participating in worldly activities, because this was part of God's purpose for each individual. Thus, labor and business became part of one's duty to God. According to Weber, with the right theological developments, this worldliness could be transformed into a belief in the duty to prosper. This connection will be made in the next two chapters. Once again, some have questioned Weber's empirical claims. It has been argued that the concept of the calling was not as new as Weber contends, and that it was already a presence in Catholic scriptural interpretation. Consider, as you read the next two chapters, the degree to which this argument could affect Weber's conclusions. Chapter 4 - The Religious Foundations of Worldly Asceticism (Part 1, Calvinism) Historically, the four major forms of ascetic Protestantism have been, Calvinism, Pietism, Methodism, and the Baptist sects. None of these churches are completely independent of each other, or even from non-ascetic churches. Even their strongest dogmatic differences were combined in various ways, and similar moral conduct can be found in all four. We see, then, that similar ethical requirements can correspond with very different dogmatic foundations. In examining these religions, Weber explains that he is interested in "the influence of those psychological sanctions which, originating in religious belief and the practice of religion, gave a direction to practical conduct and held the individual to it." People were concerned with abstract dogmas to a degree that can only be understood when we see how connected these dogmas were with practical religious interests. The first religion Weber describes is Calvinism. Calvinism's most distinctive dogma is the doctrine of predestination. Calvinists believe that God preordains which people are saved and which are damned. Calvinists came to this idea from logical necessity. Men exist for the sake of God, and to apply earthly standards of justice to God is meaningless and insulting. To question one's fate is similar to an animal complaining it wasn't born a man. Humans do not have the power to change God's decrees, and we only know that part of humanity is saved, and part damned. In the Calvinist outlook, God becomes "a transcendental being, beyond the reach of human understanding, who with His quite incomprehensible decrees has decided the fate of every individual and regulated the tiniest details of the cosmos from eternity." Weber argues that Calvinism must have had a profound psychological impact, "a feeling of unprecedented inner loneliness of the single individual." In what was the most important thing in his life, eternal salvation, each person had to follow his path alone, to meet a destiny already determined for him. No one could help him, and there was no salvation through the Church and the sacraments. This was the logical conclusion of the gradual elimination of magic from the world. There were no means at all to attain God's grace if God had decided to deny it. On the one hand, this account shows why the Calvinists rejected all sensual and emotional elements of culture and religion. Such elements were not a means to salvation and they promoted superstition. On the other hand, we see the origins of today's disillusioned and pessimistic individualism. The Calvinist's interaction with God was carried out in spiritual isolation, even though he did belong to a church. There was social organization because laboring for impersonal social usefulness was believed to be required by God. This account of Calvinism brings up an important question, however. How could the doctrine of predestination have developed in an age when one's afterlife was the most important and most certain part of existence? Each believer must have wondered if he or she was one of the elect; it must have dominated their thoughts. Calvin was sure of his own salvation, and his answer to such concerns was simply to be content with the knowledge that God has chosen, and trust in Christ. Calvin rejected in principle the assumption that people could learn from other's conduct whether they were saved or damned--this would be trying to force God's secrets. However, this approach was impossible for Calvin's followers. It was psychologically necessary that they have some means of recognizing people in a state of grace, and two such means emerged. First, it was considered an absolute duty to consider oneself to be one of the saved, and to see doubts as temptations of evil. Secondly, worldly activity was encouraged as the best means of gaining that selfconfidence. Why could worldly activity take on this level of importance? Calvinism rejected the mystical elements of Lutheranism, where humans were a vessel to be filled by God. Rather, Calvinists believed that God worked through them. Being in a state of grace meant that they were tools of divine will. Faith had to be shown in objective results. What results did Calvinists look for? They looked for any activity that increased the glory of God. Such conduct could be based directly in the Bible, or indirectly through the purposeful order of God's world. Good works were not a means to salvation, but they were a sign of having been chosen. Weber observes that Calvinism expected systematic self-control, and provided no opportunity for forgiveness of weakness. "The God of Calvinism demanded of his believers not single good works, but a life of good works combined into a unified system." This was a rational and systematic approach to life. Since people had to prove their faith through worldly activity, Calvinism demanded a kind of worldly asceticism. It led to an attitude toward one's neighbor's sins that was not sympathetic, but rather full of hate, since he was God's enemy, bearing the signs of eternal damnation. This implied a "Christianization" of life that had dramatic practical implications for the way people lived their lives. Furthermore, religions with a similar doctrine of proof had a similar influence on practical life. Predestination in its "magnificent consistency" was the foundation for the Puritans' methodical and rationalized ethics. The different branches of ascetic Protestantism had elements of Calvinist thought, even if they did not embrace Calvinism as a whole. Weber again emphasizes how fundamental the idea of proof is for his study. His theory can be understood in its purest form through the Calvinist doctrine of predestination. Calvinism did have a unique consistency and an extraordinarily powerful psychological effect. However, there is also a recurring framework for the connection between faith and conduct in the other three religions to be presented. Commentary This chapter is somewhat disjointed from the rest of Weber's study, but does attempt to show some of the main aspects of Puritan life. Calvinism is Weber's primary focus here, but in the next section he will more briefly present three other ascetic Protestant religions. In this section, Weber presents some of the most fundamental doctrines of Calvinism, as well as discussing how dogma affected practical living. There are a few key ideas to notice in Weber's discussion here. First, Calvinism was important because it stressed grace by results; there was a need for proof of one's preordained fate. This was not part of the original doctrine, but came out of psychological necessity. Second, notice the connection to the previous chapter's discussion of the Protestant calling. The sorts of "results" that Calvinists were looking for were part of worldly activity. Calvinists did not lead an isolated monastic lifestyle. They participated in the life of their communities, because this was part of God's expectations of them. It is also important to notice how Weber presents Calvinism as the height of rationalism. It has a "magnificent consistency" and encourages systematic living and the absence of magic. What does Weber mean when he says that Calvinism is "rational"? The word has important meaning to Weber, and he uses it throughout this and other works. In the context of religion, "rationalization" implies systematization and consistency, elaboration, and extension of doctrine. In terms of social institutions, rationalization implies ever-increasing knowledge in areas like calculation and efficiency. How is Calvinism rational? According to Weber, it is completely logically consistent. If you accept the Calvinists' presuppositions (such as the existence of God), then their doctrines contain no inner contradictions. Furthermore, Calvinism rejects all use of "magic," such as sacraments that will save those who partake in them. In contrast, the only hints of salvation are based on a systematic and methodical life of virtue. Calvinism was uniquely rational in these regards. Look for Weber's use of the idea of rationalization throughout this work. Chapter 4 - The Religious Foundations of Worldly Asceticism (Part 2, Pietism, Methodism, The Baptist Sects) After presenting the doctrines of Calvinism, Weber turns to three other ascetic Protestant religions, the first being Pietism. Historically, the doctrine of predestination was also the starting point of Pietism, and Pietism is closely linked to Calvinism. Pietists had a deep distrust of the Church of the theologians, and they tried to live "a life freed from all the temptations of the world and in all its details dictated by God's will." They looked for signs of rebirth in their daily activity. Pietism had a greater emphasis on the emotional side of religion than orthodox Calvinism accepted, and Lutheran strains of Pietism existed. However, insofar as the rational and ascetic elements of Pietism were dominant, the concepts necessary for Weber's study remained. First, Pietists believed that the methodical development of one's state of grace in terms of the law was a sign of grace. Secondly, they believed that God gives signs to those in states of perfection if they wait patiently. They too had an aristocracy of the elect, although there was some room for human activity to gain grace. We see that Pietism had an uncertain basis for its asceticism that made it less consistent than Calvinism. This is partly due to Lutheran influences, and partly due to emotionalism. This study thus explains some of the differences in the character of people under the influence of Pietism instead of Calvinism. Methodism represented a combination of emotional yet ascetic religion with an increasing indifference to Calvinism's doctrinal basis. Its strongest characteristic was its "methodical, systematic nature of conduct." Method was primarily used to bring about the emotional act of conversion, and the religion had a strong emotional character. Good works were only the means of knowing one's state of grace. The feeling of grace was necessary for salvation. From our viewpoint, the Methodist ethic had an uncertain foundation similar to Pietism's. Like Calvinism, they looked at conduct to assess true conversion. However, as a late product, Methodism can generally be ignored, since it doesn't add anything new to the idea of a calling. The Baptist sects (Baptists, Mennonites, and Quakers) form an independent source of ascetic Protestantism other than Calvinism; their ethics rest on a different basis. These sects are unified by the idea of a believers' church, a community of only the true believers. This worked through individual revelation, and one had to wait for the Spirit and avoid sinful attachments to the world. Despite having a different foundation than Calvinism, they too rejected all idolatry of the flesh as a detraction from the respect due God. They believed in the continued relevance of revelation. Like the Calvinists, they devalued the sacraments as a means to salvation, which was an important form of rationalization. This led to the practice of worldly asceticism. An interest in economic occupations was increased by their rejection of politics; they embraced the ethic of "honesty is the best policy." Now that we have seen the religious foundations of the Puritan idea of a calling, we can now look to the implications of this idea for the business world. The most important commonality among these sects is "the conception of the state of religious grace...as a status which marks off its possessor from the degradation of the flesh, from the world." This could not be attained by magical sacraments or good works, but could only be proved through particular kinds of conduct. The individual had an incentive to methodically supervise his own state of grace in his conduct, and thus to practice asceticism. This meant planning one's whole life systematically in accordance with God's will. Commentary These forms of ascetic Protestantism are less central to Weber's study than Calvinism, and it is therefore less important to get a complete understanding of the doctrine and lifestyle of their followers. These religions are less rational than Calvinism, because they have a strong emotional element that introduces some of the "magic" that Calvinism rejected. These religions do encourage systematic and methodical living, however, which is an important trait of rationalization. The most important tie among these different religions is their worldliness and their belief in signs of religious grace. This leaves these religions with a concept of the calling that is centered in the practical world. Look in the next chapter for how Weber connects these ideas back to the spirit of capitalism. It is important to be aware of the fact that Weber is not trying to present these beliefs in their full complexity. Each religion is being presented as what Weber called an "ideal-type." An ideal-type is a simplified version of a concept or institution, which captures its most relevant characteristics for the study at hand. In this case, Weber is ignoring much of the diversity of religious belief among these different sects, as well as many important aspects of their theology. These issues are not relevant to his study, and simplifications are necessary because of the infinite number of perspectives that could be taken on each belief, and the infinite complexity of those beliefs. All of Weber's characterizations, including the spirit of capitalism and the ethic of ascetic Protestantism, are ideal-types. Chapter 5 - Asceticism and the Spirit of Capitalism Weber now turns to the conclusion of his study, and attempts to understand the relationship between ascetic Protestantism and the spirit of capitalism. To understand how religious ideas translate into maxims for everyday conduct, one must look closely at the writings of ministers. This was the primary force in the formation of national character. For the purposes of this chapter, we can treat ascetic Protestantism as a single whole. The writings of Richard Baxter are a good model of its ethics. In his work, it is striking to see his suspicion of wealth as a dangerous temptation. His real moral objection though, is to relaxation, idleness, and distraction from the pursuit of a righteous life. Possessions are only objectionable because of this risk of relaxation; only activity promotes God's glory. Thus, wasting time is the worst of sins, because it means that time is lost in promoting God's will in a calling. Baxter preaches hard and continual mental or bodily work. This is because labor is an acceptable ascetic technique in the Western tradition, and because labor came to be seen as an end in itself, ordained as such by God. This does not change, even for those people who are wealthy, because everyone has a calling in which they should labor, and taking the opportunities for profit that God provides is part of that calling. To wish to be poor is similar to wishing to be sick, and both are morally unacceptable. Weber then attempts to clarify the ways in which the Puritan idea of the calling and asceticism influenced the development of the capitalistic way of life. First, asceticism opposed the spontaneous enjoyment of life and its opportunities. Such enjoyment leads people away from work in a calling and religion. Weber argues, "That powerful tendency toward uniformity of life, which today so immensely aids the capitalistic interest in the standardization of production, had its ideal foundations in the repudiation of all idolatry of the flesh." Furthermore, the Puritans rejected any spending of money on entertainment that didn't "serve God's glory." They felt a duty to hold and increase their possessions. It was ascetic Protestantism that gave this attitude its ethical foundation. It had the psychological effect of freeing the acquisition if goods from traditionalist ethics' inhibitions. Asceticism also condemned dishonesty and impulsive greed. The pursuit of wealth in itself was bad, but attaining it as the result of one's labor was a sign of God's blessing. Thus, the Puritan outlook favored the development of rational bourgeois economic life, and "stood at the cradle of the modern economic man." It is true that once attained, wealth had a secularizing effect. In fact, we see that the full economic effects of these religious movements actually came after the peak of religious enthusiasm. "The religious roots died out slowly, giving way to utilitarian worldliness." However, these religious roots left its more secular successor an "amazingly good" conscience about acquiring money, as long as it was done legally. The religious asceticism also gave the businessmen industrious workers, and assured him that inequality was part of God's design. Thus, one of the major elements of the spirit of modern capitalism, rational conduct based on the idea of a calling, was "born" from the spirit of Christian asceticism. The same values exist in both, with the spirit of capitalism simply lacking the religious basis. Weber observes, "The Puritan wanted to work in a calling; we are forced to do so." Asceticism helped build the "tremendous cosmos of the modern economic order." People born today have their lives determined by this mechanism. Their care for external goods has become "an iron cage." Material goods have gained an unparalleled control over the individual. The spirit of religious asceticism "has escaped from the cage," but capitalism no longer needs its support. The "idea of duty in one's calling prowls about in our lives like the ghost of dead religious beliefs." People even stop trying to justify it at all. In conclusion, Weber mentions some of the areas that a more complete study would have to explore. First, one would have to explore the impact of ascetic rationalism on other areas of life, and its historical development would have to be more rigorously traced. Furthermore, it would be necessary to investigate how Protestant asceticism was itself influenced by social conditions, including economic conditions. He says, "it is, of course, not my aim to substitute for a one-sided materialistic an equally one- sided spiritualistic causal interpretation of culture and of history." Commentary In this chapter, Weber attempts to connect asceticism with the modern capitalistic spirit. His first describes how the Puritan ethic encouraged hard work and the pursuit of profit. These claims are closely linked to Weber's observations until now. These ascetic Protestants were looking for signs of their own salvation, and their concept of the calling made them look for those signs in worldly achievements. Spending their money on luxuries was disrespectful to God, and they were expected to pour any profits back into their callings. These values are all closely linked to the capitalistic ethic, and Weber does a good job of drawing out the sources of these values. However, the next connection Weber makes is more troubling. Weber says that from this ethic, a system of capitalism emerged that no longer required ascetic values to sustain itself. These values became the capitalist spirit, and now we are all forced to follow them. However, Weber does not tell the story of how the capitalist system emerged, and by what mechanism ascetic Puritan values were replaced by something else. This suggests a gap in Weber's theoretical model. Do you consider this to be a serious gap, or is its content suggested in other parts of his work (such as Chapter 2, on the spirit of capitalism)? This section also suggests that Weber's attitude toward the modern capitalistic system is ambivalent at best. Notice his use of the imagery of an "iron cage" to describe the situation of individuals in the modern world. They are trapped in a larger system of institutions and values that define their opportunities in life. While capitalism needed ascetic Protestantism in order to become powerful, once it gained that power it took on a life of its own. We see, then, Weber's belief that capitalism's development was contingent on historical circumstances such as the Reformation. We also see Weber's belief that culture and institutions play an important role in defining people's values and opportunities.