Hiwatha (An Algonquin Story) - Toronto Catholic District School Board

advertisement

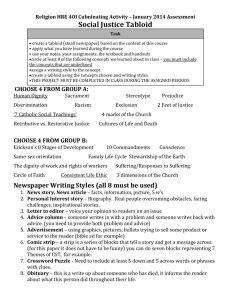

UNIT 4: Let Me Tell You a Story Time: 20 hours Unit Description Oral history and story telling have been vehicles for passing on culture and tradition for centuries. Long before the widespread literacy we enjoy today, cultures maintained faith practices and family and societal histories through story telling. Students learn the importance that story telling still holds in aboriginal cultures, and how oral communication is central to maintaining tradition. Native myths, legends and stories are studied to better understand faith and spirituality of these cultures, and compared to Catholic gospels and parables. Story telling is important for strengthening connections with relatives and older generations. Students connect with their own histories and traditions in conversation with elders in their own communities. Students’ literacy skills are strengthened in two ways in this unit; they transition from oral to written story, emphasizing the writing process, and practice and perform an oral story for elementary school students. Through the study of the story telling genre, examining myths, legends and stories, experiencing traditional Native story telling, and writing and performing their own stories, students gain an appreciation of the power of oral tradition. Unit 4 Overview Chart Time Expectations 3 TVF.03, TF2.02, hours TF3.01, PMV.01, IE1.03, IE1.04 OCSGE: 1h, 5e, 7c, 7d, 7f, 7g 7 TVF.01, TF2.04, hours TF4.01, PMV.01, PMV.02, PMV.03, PMV.04, PM2.03, PM3.03, PM4.03 Assessment -Anecdotal teacher assessment Task/Activities -study the history and tradition of Native story telling -attend the Native Cultural Centre’s Story Telling presentation -Comparative Essay -examine Native myths, legends and stories -write a comparative essay between a Native and Catholic faith story -Interview -Written Story -interview cultural elder or relative to learn a story -review short story conventions -use the writing process to record the oral story OCSGE: 1a, 1b, 4d, 6b, 7g 7 TF1.03, TF3.01, hours TF4.03, PMV.01, PMV.04, PM1.02, PM1.03, PM1.04, PM3.02 OCSGE: 1h, 4a, 4g, 6a, 6c 3 TF2.02, TF4.04, hours PMV.04, IEV.04, IE1.02, IE2.02, IE2.04 -Short story performance -practice and perform the story from the elder for elementary school students OCSGE: 3b, 4f, 5d, 5g, 6e, 7j Activity 4.1: The History of Storytelling Time: 3 hours Description and Planning Notes In this activity, students will study the history and significance of storytelling in Native culture. Through readings from the Native Drums website, students understand how storytelling factors into current aboriginal cultural practices and examine the differences between myths, legends and stories. Examples of each of these genres are studied. Students experience first hand the power of story, as they attend a traditional storytelling at Dodem Kanonhsa’, a cultural facility of the Native Canadian Centre of Toronto, and participate in a presentation of stories from various first nations in North America. Teachers should photocopy the Culture of Storytelling, and Myth, Legend and Story handouts for each student. The storytelling presentation is arranges though the Native Canadian Centre of Toronto’s Visiting Schools program at 416.964.9087. The experience at Dodem Kanonhsa’ is culturally rich as the facility is a lodge built on Ojibwa, Cree and Mohawk concepts, however, the storytellers may also come to the school. This workshop is only available in winter as per traditional protocol. Strands and Learning Expectations Strand(s): Theory and Foundation; Processes and Methods of Research; Implementation, Evaluation, Impacts, and Consequences Overall Expectations: TVF.03, PMV.01 Specific Expectations: TF2.02, TF3.01, IE1.03, IE1.04 OCSG Expectations: 1h, 5e, 7c, 7d, 7f, 7g Teaching/Learning Strategies Part A Distribute the readings and activities on storytelling. This work may be done in a variety of ways. As there is a lot of reading, it may be divided up to suit the work styles of the class. Possible delivery methods include: 1. reading the materials to students and completing the questions as a group 2. assigning the readings as independent work and taking up the questions as a group 3. having students work in groups, reading at a time stopping to take up and discuss questions The readings and questions should be discussed as a class, regardless of how the students study the materials. Discussions should include: 1. the history and significance of passing down story 2. the interdependence of story and tradition 3. relationship with the natural world 4. symbolism and metaphors 5. significance of the circle 6. characteristics of myth, legend and story 7. importance of elders and intergenerational relationships Part B Attend or host the Native Canadian Centre’s Storytelling presentation. Discussions about the presentation will take place later on in the unit, however, a wrap up conversation will help to solidify important aspects of the presentation, traditions covered, stories heard, etc. Assessment and Evaluation Anecdotal teacher assessment of class discussion and completion of the readings and activities. Activity 4.2: Native and Catholic Faith Stories: A Comparison Time: 7 hours Description and Planning Notes Stories play an active role in Catholic faith teaching. By looking at stories in our faith, it is evident that many similarities exist in how Native and Catholic beliefs are communicated. Students examine further examples of Native myths, legends and stories and choose one for comparison to a Catholic faith story. The comparison will examine how the two stories chosen are similar and different in terms of characters, morals and lessons and symbols. A strong emphasis is placed on the writing process as students will edit and peer-edit their drafts before completing the final essay. This essay should be done in class so that the process can be monitored and followed. Teachers should photocopy the More Native Myths, Legends and Stories handout, the comparative essay assignment and rubric and two editing handouts for each student. The editing sheets are the same from unit one. Strands and Learning Expectations Strand(s): Theory and Foundation; Processes and Methods of Research Overall Expectations: TVF.01, PMV.01, PMV.02, PMV.03, PMV.04 Specific Expectations: TF2.04, TF4.01, PM2.03, PM3.03, PM4.03 OCSG Expectations: 1a, 1b, 4d, 6b, 7g Teaching/Learning Strategies Distribute the comparative essay assignment and rubric, and editing handouts. Explain the assignment. Review the format of a five-paragraph comparative essay. This essay is explained as a point by point comparison on the assignment sheet, meaning that the stories will be compared on three points, with each comparison point making up one body paragraph. As a class, brainstorm some popular Catholic parables, bible stories or gospels that can be used in this assignment. Distribute the handout More Native Myths, Legends and Stories. Students may use one of these readings or one from the last activity in their comparison, but are not bound to do so. Encourage students to discover more Native stories online or at the library. Explain how the essay writing process will be emphasized and that the writing will be done in class. To this end, students must bring in copies of the two stories they are comparing. Set the timeline for the writing process and review the drafting and editing steps that were done in unit one. Remind students that they will be handing in all notes, drafts and editing checklist with their final copy. As students draft, edit and write, the teacher should use the class time to move around and conference with each student. This will allow for any individualized help and guidance the student may need. Assessment and Evaluation The comparative essay and writing process is evaluated using the rubric provided. Activity 4.3: From Oral to Written Story Time: 7 hours Description and Planning Notes Students develop writing skills in this activity as they use the writing process and knowledge of short story format to move from oral to written story. Students interview a relative or cultural elder to learn a faith or traditional story, a family history or cultural practice, myth or legend. After learning the story students will use the writing process, including visual storyboarding, to create a written version of the tale. Short story format is reviewed to help write an entertaining and organized piece. Emphasis is placed on transitioning from oral to written language as a transferable skill in all forms of writing, validating both forms of communication. Teachers should photocopy the interview sheet, short story review, the storyboard template and short story rubric. The self-editing tip sheet and peer editing checklist are used in this assignment, however, students may not need repeat copies of these handouts. Strands and Learning Expectations Strand(s): Theory and Foundation; Processes and Methods of Research Overall Expectations: PMV.01, PMV.04, Specific Expectations: TF1.03, TF3.01, TF4.03, PM1.02, PM1.03, PM1.04, PM3.02 OCSG Expectations: 1h, 4a, 4g, 6a, 6c Teaching/Learning Strategies Part A Distribute the interview sheet, short story rubric and storyboard template. Explain the assignment. Students must choose someone to interview who they feel will best give them a story to turn into a written piece. The story must be a family, cultural or faith story. Students may have to ask more than one person before finding an appropriate story for the assignment. Students are encouraged, where possible, to record the interview as opposed to trying to write down every word that is said. Review ways that students may take notes during the interview in a way that will jog their memory upon review. The point of this activity is not to retell the story verbatim, but to communicate the main message and events. Students are encouraged to enjoy the storytelling interview as an experience with the interviewee. Discuss what was learned from the storytelling presentation at Dodem Kanonhsa’ and their studies of storytelling traditions, and how this will help their interviews. Once students have their story, review short story format with the handout provided. Students will already know these terms and characteristics from grades nine and ten English, so a simple review should suffice. Have students participate in creating the definitions for the review sheet and take notes on the handout as the terms are reviewed. Part B The story writing process will begin with guided use of storyboard technique. The use of simple visual images to organize ideas will help students move the piece from an abstract oral tale, to a more fluent written story. Guide the class through each step of story writing: 1. Distribute the storyboard template. The storyboard is not intended to be a work of art. Students can use stick figures to depict events. The point is to get their ideas organized. Students are to use whatever notes and/or audio they have from their interviews to help retell the story. They are encouraged to first think about the order of events in the story. These events are then illustrated in order on the storyboard. 2. Next, students will buddy up and share their story boards with a partner. This sharing will help students see if the events flow smoothly and if all of what they want to communicate is there. Students can edit and add to their storyboards where necessary. 3. After sharing their diagrams and stories, students will begin to put words to their images. Have students write descriptions of each frame, in point form, on a separate piece of paper. This if the first step towards writing the story. After this step, students can refer to their interview notes and storyboards, but should primarily be working from this raw version of their tale. 4. Now that students have a simple version of their story, they can begin to craft the piece. It is at this point where students must decide on a narrator and be sure that their story contains all of the necessary plot points. This point would be a good one to have a mini-lesson on dialogue techniques and punctuation. Teachers often assume that students will know how to organize dialogue, but a quick review is helpful. 5. As students continue to work on their stories, encourage discussion and sharing among students. Remind them that peer editing is an important part of the writing process and that they should share ideas and advice as they write. The teacher should also be circulating around the class to conference with students and help guide their writing. Assessment and Evaluation The short story is evaluated using the attached rubric. All interview notes, storyboards, notes and drafts are to be handed in with the final draft. Activity 4.4: Sharing Story Time: 3 hours By this point in the unit, students have gained a stronger appreciation for the importance of storytelling and how culture and faith are connected to this genre. They have learned how Native and Catholic story play an important role in faith development and community building. Using the stories they inherited and recorded in the last activity, they will perform a storytelling session for elementary school students. Teachers should photocopy the storytelling rubric for each student. The workshop should be arranged with the elementary school teacher. Strands and Learning Expectations Strand(s): Theory and Foundation; Processes and Methods of Research; Implementation, Evaluation, Impacts, and Consequences Overall Expectations: PMV.04, IEV.04 Specific Expectations: TF2.02, TF4.04, IE1.02, IE2.02, IE2.04 OCSG Expectations: 3b, 4f, 5d, 5g, 6e, 7j Teaching/Learning Strategies Explain to students that they will be sharing the stories that they have inherited through the last activity with elementary students. As a class, discuss the elements of the Dodem Kanonhsa’ experience that made it entertaining, enjoyable and interesting. Discuss ways in which students can prepare to tell their stories to the elementary school audience to the same effect. Remind students that they do not have to memorize their story word-for-word, but rather focus on communicating the moral or lesson of their story. Arrange students into small groups to practice their stories and prepare for their performances. During the workshops, students should break into their practice groups, taking an equal number of elementary school children. This smaller group performance not only saves time, but also creates a more comfortable presentation forum. Have the elementary teacher help evaluate the performances. Assessment and Evaluation The storytelling will be evaluated using the attached rubric. Resources Bible Dodem Kanonhsa’ 416.952.9272 or http://www.ncct.on.ca/dodemkanonhsa.html Native Cultural Centre of Toronto 416.964.9087 or http://www.ncct.on.ca Native Drums Website http://nativedrums.ca The Circle First Peoples’ Cultures All readings and questions adapted from the Native Drums Web Site http://nativedrums.ca All of our oral histories remind us that every act is a spiritual connection to all life forces. The circle is an important symbol of that belief. It is one of our most meaningful teaching tools. Within the circle, all life is equal: “We are all related.” That belief guides how we walk, talk and view the world. An example is the Medicine Wheel. It is a circle divided into four equal parts; each part can represent, for example: one of the earth’s elements (fire, water, earth and air), one of the four seasons, one segment of the day (dawn, noon, dusk and night) or even one aspect of our human nature (spiritual, emotional, physical and mental). The east represents birth - the first stage of life, while the north is the last stage - the Elder stage. But the circle is in motion, so as spring follows winter, rebirth follows death and the perpetual cycle of creation is maintained. Personal Story from Lana Whiskeyjack, Native Drums Website: I have been a part of several Healing or Sharing Circles and have learned so much from other people as we all sat facing one another. There was no person sitting in a position of authority, everyone was made to feel equal. Each time I was a part of those circles I was reminded of where I come from and how I should think, as Elders or teachers would then begin talking about the circle and how one should treat one another. Each person would speak, one at a time, and other people listened wholeheartedly. I always left those circles feeling good and a part of a larger family or community. Like the Medicine Wheel, the drum is circular. At ceremonies, socials and powwows the drum is at the center. The singers sit in a circle facing the drum, behind them is a circle of women, then dancers, then family and friends, and so on – circles upon circles with the drum, the heartbeat of our nations at the centre. Questions: 1. What do oral histories remind us of? 2. The circle is one of the most meaningful teaching tools in First Peoples’ cultures. Explain its significance. 3. From your point of view, what does it mean that “we are all related”? How does this concept illustrate interdependence? How might the world change if we all lived by this belief? What are Oral Traditions? Excerpt from ‘Mythology and Symbols’, Lana Whiskeyjack, Writer, Native Drums Website As First Nations youth, we learn about our culture by spending a lot of time watching and listening to elders - in our homes, at gatherings and at ceremonies. Over time we learn about who we are and where we fit in. Knowledge about these important things is transmitted from one generation to the next through actions and by word of mouth. That is the way it was in the past. That is the way it is still done today. That is what is meant by oral traditions. James Lamouche defines oral tradition as, “the transmission of knowledge passed down across generations using memory and language.” (Personal interview 2005) Memory, lived experience and language converge into stories, myths, legends, songs. Through these we learn about our past, present and future. It is important to know and understand these things so that we in turn can pass on this fundamental wisdom to the next generation. Our Nations have lost a lot of traditional knowledge and languages. In many families the important connection between generations was broken when children were forced to go to residential schools where they were forbidden to speak their language and practise their cultural ways. Many traditional elders have gone to the spirit world, taking with them all they know and have experienced. Society and culture has also changed. The way we learn, think, speak and live is different from the way our ancestors lived. Today there are new ways of learning about our history and culture. We can look in a history book, or watch television, rent a DVD or search on the Internet. But our most valuable source of knowledge is still the elders who are willing to share their wisdom and experience. All we have to do is respectfully ask and they will share what they know. Reference: James Lamouche-Knibb, personal interview January 3, 2005. Excerpt from Lana Whiskeyjack, Saddle Lake First Nations (2004) Lana Whiskeyjack, Writer, “Mythology and Symbols”, Native Drums Website For a short while I lived with Nohkom (my grandmother) and she would teach me through her daily experiences. I didn’t know that I was learning until I was much older. For example, before we would leave for long walks into the bush, Nohkom would have tea and bannock set on the table in case someone would come into the house when we were not there to greet them. She said that we must always feed people, even if we have very little because the Creator will always supply us with what we need. After setting the table with cups and utensils we would leave for our walk. On our walks Nohkom would always tell me something about an animal we would see or we would play a game of ‘whose tracks or droppings?’ She would share funny stories and legends of animals or the little people. We would walk to a clearing where Nohkom had poles to stretch her hides. While she scraped hides, she would share hunting stories, and how the old people would speak to the animals. Time passed without me even knowing that I was being taught something. In the evening the tea and bannock would be gone and whoever drank and ate left some rabbit meat in the fridge. She would smudge the food we were given and I would always smile at her magical powers. That was how I learned. My experiences with Nohkom told me a lot about our people and the way we lived Questions: 1. How do we learn about our culture? 2. How does James Lamouche define oral tradition? 3. What happens to memory, lived experiences and language? 4. How do we learn about our past, present and future? 5. Name one reason why Nations have lost a lot of traditional knowledge and languages. 6. Although today there are many new ways of learning, who is still considered to be the most valuable source of knowledge? 7. What kind of knowledge did Lana Whiskeyjack’s grandmother pass onto her? Provide three examples. What Do Myths, Legends and Stories Tell Us? Stories have a life of their own. They share how one should live on earth, and with other beings. They pass on how each living being is given a special purpose in life, a purpose that benefits the well-being and survival of the community. First Peoples’ ancestors were physically, mentally, spiritually and emotionally aware of all life beings and lived their lives in relation to keeping balance with each other. Myths, legends and stories tell that rocks, animals, plants, the water, wind, earth and insects are life forms with special medicines or power and that all beings are related. In most First Peoples’ languages everything is named as a relation. For example, in prayers the animals are thanked as brothers or sisters. The belief that ‘we are all related’ is the foundation to First Peoples’ culture, spirituality and identities. Oral narrative takes one into a physical and spiritual journey, revealing proper behaviours in living in harmony and balance with all living beings. These stories teach how one should treat all living creations and remind one of who they are and where they come from. There are other stories that are meant to be humorous, to educate, and there are others meant to be taken with great respect and seriousness. Questions: 1. What do stories teach us? (i.e. What do they share? What do they pass on?) 2. What is the foundation of First Peoples’ culture, spirituality and identity? 3. How do myths, legends and stories reinforce this belief that ‘we are all related’? Provide an example. (Think about who is meant by ‘we’.) Myths, Legends, Stories Stories are the cultural and historic wealth of our people. Archaeologists can tell us about ancient artefacts and structures of the past by digging into the earth. But, as Ruth Whitehead explains, “Only in their stories do we hear the People themselves speaking about their world …”(Whitehead 1988:2). Each of our Nations has its own myths, legends, stories and songs that reflect the unique geography, history and experiences of its people. The origins of myths and legends are unknown, but many Aboriginal people believe that they came from the Creator, from animal spirits, or our ancestors. There are other beliefs that the land gave birth to stories, that each rock, tree, hill, flower carries memories of growth and changes. Myths are central stories from which other stories are braided, like legends of tricksters, small people, talking animals working with the help of water, or rocks. Michael William Francis, a Mi’kmaq elder and storyteller explained the difference between myths, legends, and stories like this. Myths are the original stories, the sacred tales that tell how things came to be in the first place. Legends pick up where myths leave off. They describe the role of culture heroes like Kluskap (Mi’kmaq), or Nanaboozhoo (Ojibwe) who helped to make the world a more liveable place for people. Stories, on the other hand, tell of historical events and personal experiences. While the content of myths and legends remains essentially the same over time, storytellers may take more liberties with stories (Franziska von Rosen, personal communication, 2005). In the Nehiyaw (Cree) culture and language there are three types of stories: acimowin is a tale of everyday experience and people usually share this type when asked how their day was; atayohkewin is a myth that has been passed down through generations; and mamahtawacimowin is a tale of miracles or incredible experiences that usually happens in spiritual journeys. Note, when reading these stories, it is important to understand that many indigenous languages in Canada are based on animate and inanimate ways of thinking and speaking. In others words, all creation is either alive or not alive. Everything has a spirit (animate) or no spirit (inanimate), but each has a purpose, a gift that contributes to the well being of the living community. Although there are many diverse languages and peoples, they all shared a common belief that ‘we are all related.’ All life forms were created equal. As you will see in the following stories, animals and birds speak, sing, teach, and communicate with people and each other. Questions: 1. Ruth Whitehead is quoted as saying, “Only in their stories do we hear the People themselves speaking about their world …”(Whitehead 1988:2). Why is it so important that “the People themselves [speak] about their world”? (i.e. Think of times when First Peoples have not been permitted to speak. What were the effects of these? (*i.e. Residential Schools, etc.)) 2. Each Nation has its own myths, legends, stories and songs. What is reflected about the people of these nations in these narratives. (3 points) 3. What is the difference between a myth, legend and story? 4. Although there are many diverse languages and peoples, what is the common belief that they all share? MYTH, LEGEND AND STORY All readings and questions adapted from the Native Drums Web Site http://nativedrums.ca A Mohawk Creation Myth Here is an example of a Mohawk Creation myth collected by Rona Rustige. She collected these stories from residents of Tyendinaga Reserve, Ontario who learned them from their grandparents and other elders. The Earth World The woman from the sky world went through the hole in the sky and fell downwards; there was only water below her. The beaver, the otter, the muskrat, and the turtle saw her fall, and fearing that she would drown sent a flock of ducks to catch her. The ducks flew underneath the woman, caught her on their backs, and set her safely down on the turtle’s shell. When she had rested she told the animals what must be done. She said that she needed soil, which could be obtained from the bottom of the sea that covered the world. The strong beaver was the first to go down towards the bottom. He was gone a very long time until finally his drowned body floated to the surface. The otter considered himself to be a much better swimmer than the beaver; he was the second to make the attempt. He was down for an even longer time, and when his body surfaced he too was dead. Finally the muskrat attempted the dive. He was underwater longer even than the otter, but his body eventually floated to the surface. The woman discovered a tiny piece of soil in the crevice of the muskrat’s paw, and this she sprinkled on the edge of the turtle’s shell. While the woman slept, the world grew from the edge of the turtle’s shell and extended as far as one could see in every direction. By the time she awoke there were willows growing along the edge of the world, and they were the first trees to grow upon the earth (Rustige 1988: 6-7). Questions: 1. Lana Whiskeyjack writes, “Everything … has a purpose, a gift that contributes to the well being of the living community. Although there are many diverse languages and peoples, they all shared a common belief that ‘we are all related.’ All life forms were created equal.” How does the Earth World demonstrate Native belief of interdependence? An Ojibwe Legend The Ojibwe have a famous legend of how the ceremonial powwow drum came to their people through a Sioux named Tailfeather Woman. This story was written in a letter to Thomas Vennum in 1970 by William Bineshi Baker, Sr., an Ojibwe drum maker from Lac Court Oreilles Reservation in northern Wisconsin. Thomas Vennum states that William Bineshi Baker began to learn his drum traditions on the lap of his father (Vennum 1982: 8). The Vision of Tailfeather Woman Here is the story of the beginning of the ceremonial powwow Drum. It was the first time when the white soldiers massacred the Indians when this Sioux woman gave four sons of hers to fight for her people. But she lost her four sons in this massacre and ran away after she knew her people were losing the war. The soldiers were after her but she ran into a lake (the location of which is never mentioned in the “preaching” of the Drum’s story). She went in the water and hid under the lily pads. While there, the Great Spirit came and spoke to her and told her, “There is only one thing for you to do.” It took four days to tell her. It was windy and the wind flipped the lily pads so she could breathe and look to see if anyone was around. No—the sound is all that she made out, but from it she remembered all the Great Spirit told her. On the fourth day at noon she came out and went to her people to see what was left from the war. (The date of this event is unknown.) The Great Spirit told her what to do: “Tell your people, if there are any left (and he told her there was), you tell your people to make a drum and tell them what I told you.” The Great Spirit taught her also the songs she knew and she told the men folks how to sing the songs. “It will be the only way you are going to stop the soldiers from killing our people.” So her people did what she said, and when the soldiers who were massacring the Indians heard the sound of the drum, they put down their arms, stood still and stopped the killing, and to this day white people are always wanting to see a powwow. This powwow drum is called in English “Sioux drum,” in Ojibwa bwaanidewe’igan. It was put here on earth before peace terms were made with the whites. After the whites saw what the Indians were doing and having a good time—the Indians had no time to fight—the white man didn’t fight. After all this took place the whites made peace terms with the Indians. So the Indians kept on the powwow. It’s because the Sioux woman lost her four sons in the war that the Great Spirit came upon her and told her to make the Drum to show that the Indians had power too, which they have but keep in secret (William Bineshi Baker, Sr. as quoted in Vennum 1982: 44-45). Questions: 1. How does the world come to be a more liveable place in the legend The Vision of Tailfeather Woman? Think of the following in order to answer: A Personal Story (Shared by Trina Shirt (Nehiyaw), Youth Advocate, Saddle Lake, First Nations) This story about the healing power of the drum is shared by Trina Sirt (Nehiyaw), a youth advocate, of Saddle Lake First Nation, Alberta (2004): When I was younger, I didn’t think of the drum. I wasn’t affected by it and didn’t believe in it. My first experience with the drum was at a powwow in Onion Lake, Saskatchewan. We camped beside some well-known champion dancers who were married. As they were walking to the arbour, the wife stepped on some medicine. Someone had put it there, someone who was probably jealous and didn’t want them to dance. [‘Medicine’ can be thoughts, words, or actions, harmful if not used in the right way.] The medicine hurt her; she couldn’t walk. Her husband carried her back to their camp. He went back to the arbour where everyone was dancing and blew a whistle for her. He blew it so that he may call for help for his wife. It was then I felt the power of the drum. It was like I heard buffalo nearby. People were crying from the power of that drum, song, dance and whistle. You could feel the drumbeat within your chest. Every time that dancer’s foot hit the ground, I could feel it. I cried. I could feel the power of healing go through me. It was a powerful healing song. If you believe in it, it is effective. That dancer danced with all his heart. He danced to call for spiritual help for his wife so that she could dance again and be healed. Some say his love healed her. He gave tobacco and gifts to the Elders who also helped by praying. Later on, his wife danced, she danced jingle. Questions: 1. What stayed with you the most about this story? What did you learn from it? 2. Ms. Shirt speaks of “the power of that drum”. What made it so powerful? MORE NATIVE MYTHS, LEGENDS AND STORIES All readings from the Native Drums Web Site http://nativedrums.ca The Wolf Clan and the Salmon (A Story from the Northwest Coast) “A story from the Nass River illustrates this. It tells how, in a canyon near the head of the river, there was a wonderful place that the tribespeople could always visit to find salmon and wild berries. The villagers who lived nearby were wealthy enough to trade with others and much respected. As time went on, the younger people forgot the old traditions; sometimes they killed small animals and left the carcasses for the crows and eagles to eat. Their elders warned them that the Chief in the Sky would be angered by such foolish behaviour, but nobody heeded them. In one case, when the salmon season was at its height and the fish were swimming up river in their myriads, some of the young men of the Wolf Clan thought it amusing to catch salmon, make slits in the fish’s backs, put in pieces of burning pitch pine, and put them back in the water so that they swam about like living torches in the river. It was spectacular and exciting, and they did not think about the cruelty to the salmon, or the waste of a good food. The elders as usual protested and as usual the young people took no notice. At the end of the salmon run season the tribe made ready for the winter ceremonies. But as they prepared they heard a strange noise in the distance, something like the beating of a medicine drum, and grew worried. As there was nothing very threatening about it, the young people said, ‘Aha, the ghosts wake up, they are going to have a feast too.’ The old people guessed that the young men’s thoughtlessness in ill-treating the salmon had brought trouble on the tribe. After a while the noises died down, but within a week or two the beating of drums became louder and louder. Even the young warriors became very careful about what they did, because they were frightened. The old people noted the young men’s fear, and said it would be their fault if the tribe perished. Eventually a noise like thunder was heard, the mountains broke open, and fire gushed forth until it seemed that all the rivers were afire. The people tried to escape, but as the fire came down the river, the forest caught fire and only a few of them got away. The cause of the conflagration was said by the shamans to be entirely due to the anger of the spirit world at the torture of the salmon. Thus the powers of nature insisted on a proper regard for all their creatures (Burland 1965: 36-37). Crow Indian Water Medicine (A Crow Legend) Long ago, somewhere across the plains, there was a Crow Indian who had lost his son in a war. Stricken with grief, he went up into the mountains to pray and wait for a vision that would help him avenge the death of his son. He slept ten nights. Finally, while in a deep sleep, he had a dream. In his dream he heard singing and drumming. A man came to him and invited him to a place where there was dancing. He followed the man to a lodge where there were many old men and women. “There were eight men with drums. He also saw weasel skins, skins of mink and otter, a whistle, a smudge-stick, some wild turnip for the smudge, and some berry-soup in a kettle. One old woman had an otter skin with weasel-skin around it like a belt.” (Wissler and Duvall 1995 (reprinted): 80-81) The Crow Indian stayed there and learned songs the people sang. When he awoke, he returned to his people and brought back the powerful Crow-water-medicine. If people wished for things, the Crow man would bring out his water medicine and they would sing, pray and dance. After awhile, in some way, the wish would come true. Water medicine is very powerful not only in treating the sick but because water is vital in the prairies. Ceremonies like the Sundance revolve in honouring and requesting for water. Hiwatha (An Algonquin Story) When Hiwatha was small, he lived with his grandmother Nokomis. He always wanted to sing. Nokomis told him: “You must go into the forest and listen to the birds sing, and you must learn to imitate them.” Then, each morning at dawn, Hiwatha set off for the woods to listen to the birds, but he could not reproduce their songs. Once more, his grandmother told him: “You must try again.” The next morning Hiwatha returned to the forest: he listened and listened to the birds, and tried to imitate their songs. Suddenly he heard extraordinary music coming from far away. Walking slowly, he followed the echo and arrived at a large waterfall. It was this waterfall that had produced the music. Soon, Hiwatha began to sing and he called the song: “Laughing Waters”. He carved an alder flute and played his song. Consequently each time Hiwatha returned to the woods, he always took with him his flute. He played and sang to the birds his song about the laughing waters. “And that was how First Peoples obtained their music,” said White Caribou Woman (Wa Ba Die Kwe) [Clément/Martin 1993: 83]. Elderberry Flute Song (A Poem and Modern Iroquoian Myth) (This is a modern Iroquoian myth about the flute. It is a poem by Peter Blue Cloud (in Conlon 1983: 12). Peter Blue Cloud (Turtle Clan) is a Mohawk from Kahnewake, Quebec.) He raised the flute to his lips sweetened by springtime and slowly played a note which hung for many seasons above Creation. And creation was content in the knowledge of music. Then note followed note in a melody which wove the fabric of first life. The sun gave warmth to waiting seedlings, and thus were born the vast multitudes from the song of the flute. Comparative Essay Assignment A comparative essay examines the similarities and differences of two or more things. In this essay, you will compare a Native myth, legend or story with a Catholic faith story. Choose one Native myth, legend or story, and one Catholic parable, bible story or gospel. You will compare these two readings in terms of their characters, lessons/morals and symbols. Your five-paragraph essay must follow this format: Introduction one paragraph, about 7 sentences long briefly summarize each story thesis statement must list the three points of comparison Body three paragraphs, one for each point of comparison, each about 10 sentences long each paragraph compares the two stories on one point from the thesis the order of the body paragraphs must follow the order of the points in the thesis use specific examples from each story to support your ideas Conclusion one paragraph, about 7 sentences long summarize your main points concluding statement All of your essay writing will be done in class so that you may conference with your teacher and edit and peer edit your work. You must hand in the attached comparison chart, all notes, drafts, a copy of each story and bibliography with your final essay and rubric. Your essay will be evaluated using the attached rubric. Comparison Chart Native Selection Title: Characters Moral/Lesson Symbols Catholic Selection Title: Comparative Essay Category Thinking Analyse concepts Analyse concepts providing details Analyse how the ideas and issues interrelate Critically analyse ideas, arguments, and bias found in resources Evaluate information to identify supporting details Evaluate information using supporting factual details Communication Communicate information effectively Communicate information using an appropriate format Describe ways in which each story are similar and different Application Analyse the different perspectives in each story Apply proper conventions of standard English Apply the writing process Demonstrate ability to apply critical thinking strategies Use criteria to make a comparison Level 1 Level 2 Level 3 Level 4 Conclusions have limited factual support Analysis of concepts provides limited details Conclusions have some factual support Analysis of concepts provides some details Conclusions have thorough factual support Analysis of concepts provides thorough details Analysis demonstrates limited use of critical thinking Demonstrates limited ability to critically analyse resources Evaluation of information demonstrates limited understanding Evaluates information using few supporting factual details Analysis demonstrates some use of critical thinking Demonstrates some ability to critically analyse resources Evaluates information using some supporting factual details Conclusions have considerable factual support Analysis of concepts provides considerable details Analysis demonstrates considerable use of critical thinking Demonstrates considerable ability to critically analyse resources Evaluation of information demonstrates considerable understanding Evaluates information using many supporting factual details Communicates with limited effectiveness Limited ability to use an appropriate format Description provides limited detail Communicates with some effectiveness Some ability to use an appropriate format Description provides some detail Communicates with considerable effectiveness Considerable ability to use an appropriate format Description provides considerable detail Communicates with a high level of effectiveness A high level of ability to use an appropriate format Description provides thorough detail Analysis demonstrates limited knowledge Analysis demonstrates some knowledge Many errors make writing difficult to understand Does not apply the writing process effectively Limited ability to apply critical thinking strategies Many errors, but information can be understood Applies some steps of the writing process effectively Some ability to apply critical thinking strategies Analysis demonstrates considerable knowledge Some errors Analysis demonstrates thorough knowledge Few errors Rarely uses criteria to make a comparison Sometimes uses criteria to make a comparison Applies some steps of the writing process effectively Considerable ability to apply critical thinking strategies Often uses criteria to make a comparison Applies all steps of the writing process effectively A high level of ability to apply critical thinking strategies Routinely uses criteria to make a comparison Evaluation of information demonstrates some understanding Analysis demonstrates a high level of use of critical thinking Demonstrates a high level of ability to critically analyse resources Evaluation of information demonstrates thorough understanding Evaluates information using a wide range of supporting factual details Story Interview Interviewer: Interviewee: Date of Interview: Place of Interview: Interviewee Background/Relationship to Interviewer: Origin of Story/Genre: Story Notes: Short Story Review Plot Diagram CLIMAX DENOUEMENT RISING ACTION RESOLUTION CONFLICT INCITING INCIDENT Definitions Conflict Inciting Incident Rising Action Climax Denouement Resolution Theme Narrator/Narrative point of view Setting Protagonist Antagonist Storyboard You can continue your storyboard on a separate sheet of paper. Short Story Category Knowledge Demonstrate understand of the skills/attitudes required for research Level 1 Level 2 Level 3 Level 4 Limited understanding of the skills/attitudes required for research Some understanding of the skills/attitudes required for research Considerable understanding of the skills/attitudes required for research Thorough understanding of the skills/attitudes required for research Limited analysis Some analysis Considerable analysis Thorough analysis Analysis of subject’s views demonstrates limited ability to make connections Limited ability to access appropriate resources Analysis of subject’s views demonstrates some ability to make connections Some ability to access appropriate resources Analysis of subject’s views demonstrates considerable ability to make connections Considerable ability to access appropriate resources Analysis of subject’s views demonstrates a high level of ability to make connections A high level ability to access appropriate resources Evaluates information with limited use of criteria Evaluates information with some use of criteria Evaluates information with considerable use of criteria Evaluates information with thorough use of criteria Limited ability to communicate using an appropriate format Some ability to communicate using an appropriate format Demonstrates ability to communicate and present information Limited ability to communicate and present information Some ability to communicate and present information Formulate questions for a variety of research purposes Formulate questions with limited clarity Formulate questions with some clarity Considerable ability to communicate using an appropriate format Considerable ability to communicate and present information Formulate questions with considerable clarity A high level of ability to communicate using an appropriate format A high level ability to communicate and present information Formulate questions with a high degree of clarity Many errors make writing difficult to understand Does not apply the writing Many errors, but information can be understood Some errors Few errors Applies some steps of the Applies most steps the writing Applies all steps of the writing Thinking Analyse and explain key elements of the piece Analyse how each subject views the role of personal experience Be able to access appropriate resources using various strategies and technologies Evaluate information using criteria developed in class Communication Communicate information using an appropriate format Application Apply proper conventions of standard English Apply the writing process Demonstrate ability to apply creative thinking strategies Develop and apply effective criteria for evaluating the quality of your project Use thinking skills to develop effective interdisciplinary products/activities process effectively Limited ability to apply creative thinking strategies writing process effectively Some ability to apply creative thinking strategies Develops and applies criteria with limited effectiveness Develops and applies criteria with some effectiveness Limited ability to use thinking skills Some ability to use thinking skills process effectively Considerable ability to apply creative thinking strategies Develops and applies criteria with considerable effectiveness Considerable ability to use thinking skills process effectively A high level ability to apply creative thinking strategies Develops and applies criteria with a high degree of effectiveness A high level ability to use thinking skills Storytelling Workshop Category Knowledge Demonstrate understanding of the collaborative attitudes and skills required Thinking Explain concept in an organized manner Level 1 Level 2 Level 3 Level 4 Demonstrates limited understanding Demonstrates some understanding Demonstrates considerable understanding Demonstrates thorough understanding Explanation demonstrates limited organization Explanation demonstrates some organization Explanation demonstrates considerable organization Explanation demonstrates thorough organization Communication Communicate information clearly Communicates with limited clarity Communicates with some clarity Communicate information effectively Communicates with limited effectiveness Communicates with some effectiveness Communicates with considerable clarity Communicates with considerable effectiveness Communicate information using appropriate style Limited ability to communicate using appropriate style Some ability to communicate using appropriate style Considerable ability to communicate using appropriate style Communicates with a high degree of clarity Communicates with a high degree of effectiveness A high level of ability to communicate using appropriate style Demonstrates limited ability to apply creative thinking strategies Demonstrates some ability to apply creative thinking strategies Demonstrates limited use of skills and strategies Demonstrates some use of skills and strategies Demonstrates considerable ability to apply creative thinking strategies Demonstrates considerable use of skills and strategies Demonstrates a high level of ability to apply creative thinking strategies Demonstrates thorough use of skills and strategies Demonstrates limited ability to develop effective products and activities Demonstrates some ability to develop effective products and activities Demonstrates considerable ability to develop effective products and activities Demonstrates a high level of ability to develop effective products and activities Application Demonstrate ability to apply creative thinking strategies Demonstrates skills and strategies used to develop products and activities Use thinking skills to develop effective interdisciplinary products and activities