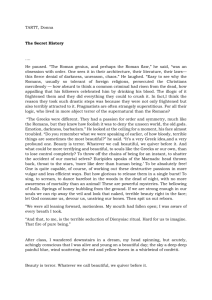

Enjoyment and Beauty - Chicago

advertisement