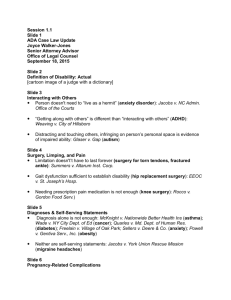

ADAAA_case summaries_3_27_13_

advertisement