Oceans 11

advertisement

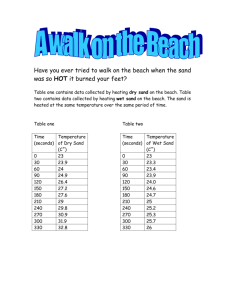

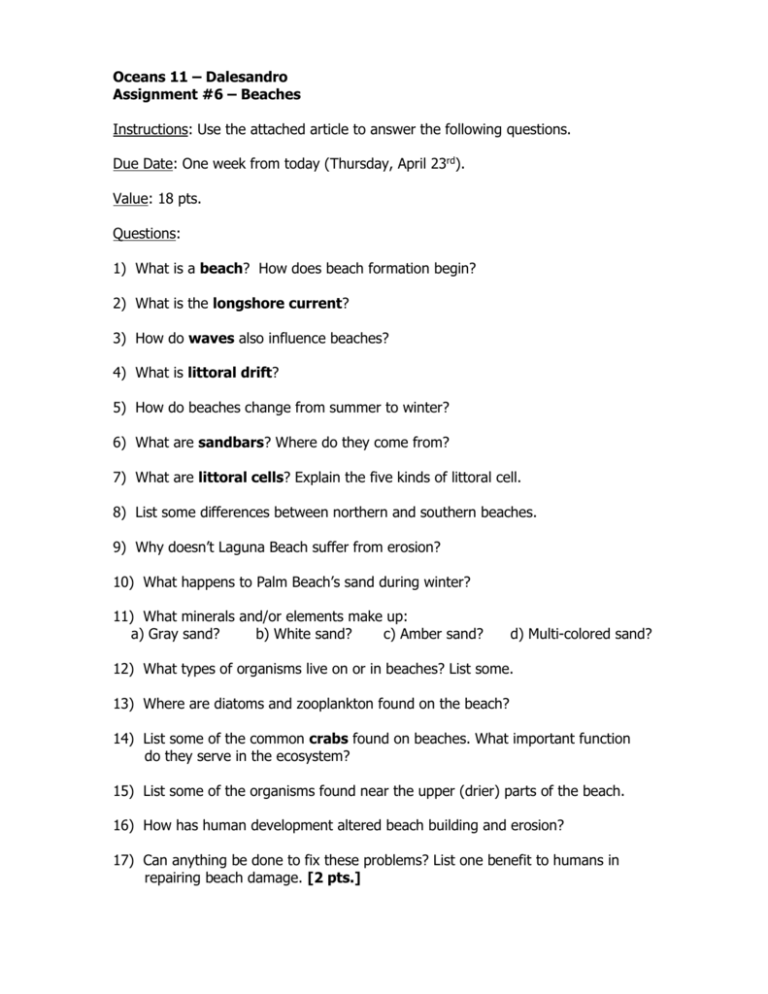

Oceans 11 – Dalesandro Assignment #6 – Beaches Instructions: Use the attached article to answer the following questions. Due Date: One week from today (Thursday, April 23rd). Value: 18 pts. Questions: 1) What is a beach? How does beach formation begin? 2) What is the longshore current? 3) How do waves also influence beaches? 4) What is littoral drift? 5) How do beaches change from summer to winter? 6) What are sandbars? Where do they come from? 7) What are littoral cells? Explain the five kinds of littoral cell. 8) List some differences between northern and southern beaches. 9) Why doesn’t Laguna Beach suffer from erosion? 10) What happens to Palm Beach’s sand during winter? 11) What minerals and/or elements make up: a) Gray sand? b) White sand? c) Amber sand? d) Multi-colored sand? 12) What types of organisms live on or in beaches? List some. 13) Where are diatoms and zooplankton found on the beach? 14) List some of the common crabs found on beaches. What important function do they serve in the ecosystem? 15) List some of the organisms found near the upper (drier) parts of the beach. 16) How has human development altered beach building and erosion? 17) Can anything be done to fix these problems? List one benefit to humans in repairing beach damage. [2 pts.] Beach Formation, Types of Beaches, and Sand Beaches are dynamic landforms in the littoral zone. They are created from sediment and altered by wind and waves in a continual process of build-up and erosion. Beach formation begins as eroded continental material – sand, gravel, and pebble fragments – are washed to sea by streams and rivers. This results in the deposit of sand and sediment on the shore. Most sediment is suspended in sea water and transported along the coast by the longshore current, a stream of water flowing parallel to the beach that is created by the action of breaking waves. Longshore transport can deliver up to a million cubic metres of sediment annually to a single beach. In another process, sand deposited onshore by the longshore current is then oscillated (moved back and forth) by waves breaking onto and receding from the beach. This continual onshore-offshore movement gradually pushes the sand along the beach edge. Both the longshore transport of sediment along the coast and the movement of sand by waves along the beach are parts of the process known as littoral drift. Seasonal cycles of sand deposition and loss dramatically affect the appearance of beaches from summer to winter. Wide and gently sloping in summer, they become steep-fronted and narrow in winter, and can vanish overnight, stripped of sand by violent storm waves. Most of the sand removed from winter beaches is deposited in offshore sandbars and is returned to the beach during the mild summer months by gentle swells that push the sand to the exposed shore. River sediments are the source of 80 to 90 per cent of beach sand; the rest comes from ocean sediment, parrotfish feces, and other sources. Some beaches are built to great widths by sediments washed to the sea in times of flooding, gradually eroding until the next major flood replenishes the sand. The coastline can be divided into geographic segments called littoral cells, that incorporate a complete cycle of beach sediment supply, sand transport by the longshore current, and eventual permanent loss of sand from the littoral cell. The five types of littoral cells are each characterized by a different littoral process determined by the geographic features unique to the cell type. One type of cell is defined by a long stretch of coastline that begins at a headland and terminates in an underwater canyon. Another cell type consists of a large river delta bounded on either side by rocky headlands. A third type of littoral cell is defined by a crescent-shaped piece of coast surrounded by cliffs. A fourth type of cell consists of a rocky beach where waves break in a line parallel to the shore. Finally, lagoons and closed bays with restricted tidal flow create a fifth type of littoral cell. Apart from littoral cell type, there are characteristic differences between Northern and Southern beaches, depending upon the directions of prevailing wind and upon local coastal geology. Along the north coast of North America, cove or pocket beaches are common where the rocks that make up the sea cliffs have been shaped by prevailing northwesterly winds and battered by high energy waves over millions of years. In southern areas, beaches often consist of long ribbons of sand interrupted by widely separated rocky points. The bluffs of easily eroded shales and sandstones that edge the coast here continuously crumble away, creating a smooth, even coastline. Some beach types are found along both northern and southern coasts. Narrow cove beaches like those at Laguna Beach, California form where the coast is composed of hard sandstone. Even when exposed to direct wave attack this tough rock is highly resistant to erosion. The narrow beaches formed within there coves often lose all their sand during winter storms, exposing the underlying cobbles, as at Palm Beach, Florida. Beaches vary in color according to the mineral content of the sand, which is also a clue to the origin to the eroded sediments that make up the sand supply. Eroded shale cliffs create charcoal gray beach sand. Multicolored sand is usually made up of various types of rock that have been ground and polished by the surf. Ground quartz and feldspar minerals make up white beaches, while amber-colored sand indicates the presence of iron in the rock. Close inspection may reveal traces of pink, green, white, and black sand grains in all beaches, even those we call “white sand”! Beaches are inhabited by a variety of invertebrates and insects. In the surf zone, bivalve mollusks, crustaceans, and tube-building sandworms adapt to their environment of tide cycles and waves by burrowing to protect themselves from wave impact, temperature fluctuations, drying-out, and predators. The smooth shells of clams and other burrowers reduce friction when they tunnel through the fine sandy beaches of their preferred habitat. At low tide, water retained between the sand particles is filled with millions of microscopic diatoms and zooplankton upon which the buried bivalves feed, using long siphons that reach to the sand surface. Fine screens within the siphons filter out sand particles by allow the passage of water and suspended organic material that provide an abundant food supply for the filter- feeding bivalves. Razor clams, surf clams and coquina clams are common burrowers inside beaches. Pismo clams occupy a special niche in the surf zone, welladapted to the crashing surf by nature of their large, heavy shells, which act as anchors. these giant clams are dependent upon the high-oxygen content of the roiling surf to survive. Inland from the surf zone, sand crabs scavenge in the sun-dried kelp and bury in the sand, using their antennae to rake food particles to their mouths. Kelp flies, wrack flies, rove beetles, tiger beetles, and dune beetles roam the beach foreshore. The dry upper littoral and supra-littoral zones are inhabited by air-breathing pill bugs, sand lice, barnacles, and beach hoppers. Numerous beetle species inhabit the dunes, some burrowing in the sand during the day to escape predators and the heat. Birds of all types congregate on the beach to feed. The natural process of beach building and erosion has been altered by extensive development of most coastlines. Prior to development, natural loss of sand from beaches, largely to dunes and submarine canyons, and natural sand supply, mostly from rivers and streams, were roughly in balance. The natural balance of beach sand supply and loss has been altered by the construction of offshore breakwaters, barriers, and jetties, which may divert sand from one location to another and change beach shape. In a few locations, however, large-scale beach nourishment projects have created wide beaches that may last several decades or more before eroding away. These projects pull in tourists and drive local economies.