Communication: Complex needs

advertisement

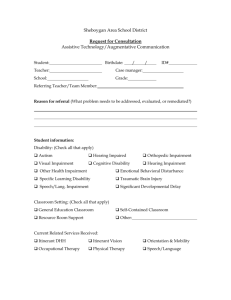

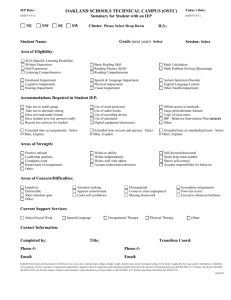

RNIB supporting blind and partially sighted people Effective practice guide Communication: Complex needs This guide covers developing skills in communicating with children with complex needs, including the use of communication technology, touch and objects of reference. It includes contributions from speech and language therapists and those by senior lecturers in the Visual Impairment Centre for Teaching and Research, at the School of Education, University of Birmingham. Contents Part 1: Alternative and augmentative communication (AAC) Part 2: Objects of Reference Part 3: Promoting communication in children with complex needs Part 4: Becoming a sensitive communication partner Part 5: Using Touch with children with complex needs Part 6: Further guides Registered charity number 226227 Part 1: Alternative and augmentative communication (AAC) About this part This part gives explores the use of Communication Technology or Alternative and Augmentative Communication for children with severe vision impairment and complex needs. Written by Caroline Knight, Speech and Language Therapist, this guide looks at how technological devices can be used to help children learn and communicate to express their choices. Contents: 1.1. Communication Technology 1.2. Total Communication 1.3. Developing Switching Skills 1.4. Factors in choosing a switch 1.5. Single message devices 1.6. Sequencing devices 1.7. Making Choices: auditory scanning 1.8. Making choices: direct access 1.1. Communication Technology Technological devices can help children learn to communicate and express choices. This is also sometimes referred to as Alternative and Augmentative Communication (AAC). For children with a vision impairment and multiple disabilities (MDVI), the path to effective communication can be very long and difficult to negotiate. The outcomes rely on the quality of the interactions of their caregivers, their environment and the opportunities that they are given. 1.2. Total Communication Children with MDVI can benefit from a Total Communication environment, where a variety of means of communication is available to them. With perseverance, understanding can be developed and the communication of basic wants and needs can be established through a variety of channels. Children with a vision impairment can perceive the world to be fragmented and chaotic. But technology can provide a constant and consistent route to communication. Technology can enable the child to experience control over their environment; it can facilitate interaction; it can present the child with a means to become an active communicator; and it can provide opportunities to communicate with a wider world. 1.3. Developing switching skills If our ultimate goal is to enable a child to use technology to enhance their expressive communication, then we must first consider how the child will gain access to the devices. Typically this is via a switch. To ensure that the switch is used meaningfully, we need to ascertain the most accurate repeatable body movement - with the least amount of effort - which the child can produce. This will determine what type of switch should be used. This can be found by careful observation of how the child moves and interacts with objects and providing lots of opportunities to practice and refine skills. 1.4. Factors in choosing a switch How the switch is activated Types of switch include: simple press switches such as a Jelly Bean or Buddy Button flat pad switches which require only a slight touch such as a Pal Pad or Wolfson Touch Switch a String Switch which can be activated by the pull of the string loop such as by raising an arm a Wobble Switch which can be operated by a gross movement of an arm or leg - no precision needed a Tilt Switch which can be attached to the body and reacts to very small movements a tactile overlay on an alternative keyboard such as Intellikeys. Note that the child's most consistent movement may not be fingers: children may use, amongst other possibilities, their fist, back of hand, back of head, side of head, wrist, foot or knee. It is generally agreed that it is easier for a child to understand they are in control via the switch if they are able to have direct contact with it. Size of the switch This will depend on how it will be activated and the accuracy of child's movement. Positioning of the switch Consult the child's Occupational Therapist to ensure that good movement patterns are established. Be consistent so that child does not have to search to locate the switch each time. Have the switch available for prolonged periods, not just when the adult wants to draw attention to it. The child should purposefully select to use the switch to achieve an end, and not because it has suddenly been presented to him. The use of a mounting arm can lock the switch securely into the required position. Consider using a wireless switch such as the Jelly Beamer so that there is less to distract the child or for the child to get caught up in. Consider mounting the switch on the child, for example with a Velcro band around their leg, so that the child is aware of the position. Differentiation of the switch To help the child distinguish the switch from the rest of their environment, use switch caps to introduce texture or a contrasting colour or reflective surface. Use different switch covers to help the child distinguish the different rewards. Or place the different switches in consistent locations. Supporting switching Switching can be cued with verbal prompts such "one, two, press" (and then faded as the child anticipates and takes control). Rewards Provide rewards or outcomes that are motivating to the child and will have a clear impact on the child, such as a change to their immediate environment. Switches using devices such as Battery Switch Adapters and the AbleNet PowerLink can control both battery and electrical toys and appliances. These can increase the range of rewards that can be offered. The following could be considered: cool fan (perhaps with streamers added) warm hairdryer massager vibrating cushion foot spa recordings of novel music or sounds (you could use a site like FindSounds for this) lights bubble tube computer - patterns on screen, animation. Presenting switches will help develop and consolidate the child's understanding of cause and effect. The child becomes active in their environment and experiences the power of taking control. These abilities can be developed through individual exploration and through play with an adult. The skills that are learned and practiced, such as maintaining attention, anticipation and turn taking, can be transferred to other areas of the child's communication. 1.5. Single message devices Individuals who can use switches purposefully and demonstrate a need and desire to communicate may benefit from using a Voice Output Communication Aid (VOCA). Liaise with the child's Speech and Language Therapist to determine the complexity of language that is appropriate, eg single words, short phrases or sentences. Using a single message VOCA, eg the BIGmack, lets the child build a link between the message and its effect on the communication partner. In a busy schedule, the adult usually records the message at the start of the activity. Ideally, the messages should be recorded by a consistent person - where possible of the same age and sex as the child, but not known to them. Adults should also use the VOCA to model how to use it appropriately, so the child has experience of hearing a VOCA in familiar communication exchanges. For example, class staff could use a VOCA as they greet students and each other in the morning circle. Example messages Messages may be sounds, single words or short phrases. Initially the child should begin with the switch in a non-time-dependent context, ie when there is no pressure to use it within any framework set by the adult. Examples may include: "Hello" - as a general way to gain someone's attention "Let's talk" - to initiate an interaction "Go away!" - to clear the room person by person "Woof woof" - to provide sound effects in a story about a dog. Adults should reinforce the use of the message by responding as if the child had spoken the message. Time dependent messages Once the child is using the message with meaning and shows an awareness of the message as a communication to others, then opportunities that are time dependent can be used. These may include: responding to a greeting in circle time a train whistle - to sound whilst the train runs around the track, jingling bells or a crashing cymbal to use during a music session saying "Ready, steady, go" to start a game or a song saying "Knock it down!" to topple a tower of bricks asking for "more" at snack time providing a repeated line in a song or story. 1.6. Sequencing devices Some VOCAs, eg the Step by Step, can offer a sequence of messages which can give more possibilities for the child to participate. The child cannot determine the order of the messages but can control the timing of their delivery. These can be used in a variety of ways to provide motivating communicative experiences for the child: songs can be played one line at a time a list of animals can recorded to be used at the appropriate time when "Old Macdonald" is being sung children's names can be listed and supplied to the teacher a when a 'volunteer' is needed a list of commands can be given for a simplified game of Simon Says - "clap your hands", "everybody whistle", etc a shopping list can be accessed when in the supermarket a sequence of commands will allow the child to prompt himself during an independent activity. 1.7. Making choices: auditory scanning If the child is unable to access the communication aid physically, other means can be investigated. It is common practice to give spoken alternatives in order to elicit a response from a child: for example, "Do you want yoghurt, banana or custard?" In doing this we are using a form of auditory scanning. Technology can replicate and extend this technique by giving the child a sequence of prompt words or phrases. In its simplest form, the child activates a switch on hearing the required response, and the word or phrase is repeated. A greater number of choices can be made available to the child by "branching" - using categories that can lead the child to navigate through multiple layers of vocabulary. For example, the child may be prompted with "People, Food, Play". If he responds to "People" he may then be given the choice of "Mum, Dad, Brother, Friend" etc. Glennen & Decoste state: "Auditory scanning has elements of motor and auditory discrimination skills and is cognitively demanding". To be successful with this type of system, the user needs to be able to: listen and pay attention understand the concept of cause and effect listen and activate after a targeted message master one consistent motor movement demonstrate good comprehension skills retain and recall. If the child is able to cope with this, auditory scanning can offer an effective means of communication. However, for many MDVI children, the challenges of this form of communication prove to be too great. 1.8. Making choices: direct access By giving auditory feedback and reinforcement, VOCAs offer a good way to facilitate choice making. The child can be facilitated to move on from using a single-message VOCA to having a choice of two. Initially it can be helpful if one of the choices results in a motivating outcome and the other is more neutral. (This tactic can sometimes lead to the child being able to demonstrate previously unknown preferences, such as a young child who consistently played Gregorian chant rather than the adults' presumed favourite of a lively pop hit!) Simple VOCAs that offer two, four or even eight message cells could also be introduced gradually. Remember that just because the device has four cells, you do not have to fill them all. Leaving some blank spaces may help the child locate those that are in use. As with the switches mentioned above, the cells need to be differentiated so that the child can find the desired message. Different meanings could be denoted by the use of tactile markers, eg textures, miniature objects, parts of known objects or blocks of colour, clear photographs or colour. These could be attached directly onto the switch or cell, or onto an overlay, depending on the device in use. Where multiple choices are available, a key guard can often assist the child in finding the required message without activating unwanted messages. Part 2: Objects of Reference About this part This part considers the shortcomings of speech and sign and explores the use of Objects of Reference to aid communication. Ian Bell is a teacher and speech and language therapist with considerable experience of children with special needs, including those with severe vision impairment and complex needs, and those with autism. Ian is a member of the Visual Impairment and Autism Project team, looking at the provision for children who have both severe vision impairment and autistic spectrum conditions. Contents: 2.1. Shortcomings of speech and sign 2.2. What is an object of reference? 2.3. How can objects of reference help communication? 2.4. Use and misuse of objects of reference 2.5. References 2.1. Shortcomings of speech and sign Many children with vision impairment and complex needs have significant difficulties processing and interpreting auditory and visual information. Spoken words and manual signs are fleeting and usually bear no direct resemblance to the items they refer to. Some children with vision impairment and complex needs frequently move in and out of alertness, and this may be especially true of those who also have poorly-controlled epilepsy. In addition, many children with vision impairment and complex needs have difficulty focusing their attention. It is not surprising, then, that they often fail to attend to something as brief as a spoken word or manual sign. Their difficulties continue even if they do attend. This is because they also process information slowly. By the time they have interpreted and understood what they have heard or seen, events may well have moved on, leaving them confused. Some children with vision impairment and complex needs find it is easier to understand when they handle an object. If a child learns to attach a special meaning to an object, that object is regarded as an "object of reference". 2.2. What is an Object of Reference? An object of reference can enable the child to obtain information from several senses: touch, vision (if they have some useful sight), smell, taste, and sound (e.g. if they bang it against a surface). This is more reliable for them than relying only on hearing the spoken word, even if that is accompanied by a manual sign. The best way to describe objects of reference is to give a couple of examples. Afzal, who had no functional vision, often became distressed in school when it was time to go home: she did not understand where she was being taken. Because Afzal always held on to her seatbelt in the car, it was decided to present her with a piece of seatbelt webbing immediately before going to the car. It was hoped that this would help her to understand she was going in the car. Each time the webbing was presented, the person giving it to her also said "Afzal; car." After a few days, Afzal relaxed as soon as she was given the webbing. She had attached the special meaning of "car" to the webbing and thus it had become a true object of reference for her; it supported her understanding. Karl, who had a little useful vision, loved to play with a train set, but did not have the means to ask for it. It was decided that he should be taught to hand a section of track to a member of staff who would then immediately provide him with the train set. Karl soon got the basic idea and, after a carefully structured programme, he would spontaneously go to the bottom shelf near the classroom door, find the track and hand it to a member of staff. Karl had attached the special meaning of "train set" to the track and thus it had become a true object of reference for him; it supported his expressive communication. 2.3. How can objects of reference help communication? Objects of reference, then, can play a key part in supporting communication for a child with vision impairment and complex needs: they can help the child to understand what other people say provide a means for the child to express needs and wants. If you feel an individual child might benefit from objects of reference, you need to proceed with care at first. It may be necessary to go through a period of trial and error. This is because you cannot know for sure whether the child will attach a special meaning to the object you select. In addition, it will take time for the child to build up a link between the object and the item, place, person, event, activity or experience it refers to. 2.4. Use and misuse of objects of reference Being child-specific It is sometimes argued that objects of reference should be standardised throughout a school. It is very strongly recommended here that each object of reference is child-specific; for Afzal the webbing was the correct object of reference for "car" because she held onto her seatbelt whilst in the car. Thus she could readily associate the webbing with the experience of going in the car. However, as soon as Robert got in the car he stretched out his hand to feel the drop-down table on the back of the front seat. He showed no interest in the seatbelt, so he would have been unlikely to attach the special meaning "car" to a piece of webbing; instead, his object of reference was an identical drop-down table donated by the local garage. Another factor to bear in mind is what will happen when the child moves to another school, or leaves school and goes to college. If child-specific objects of reference have been used, these can readily transfer to the new setting with the child. However, if a standard set has been used in school one, and another, different, set in school two, communication will break down and the child is likely to become very bewildered and frustrated. Location markers In some schools, objects are employed to mark specific locations. For example, a spoon is provided at the entrance to the dining hall, a piece of mat outside the gym. Objects used in this way obviously have to be standardised for all children. However, rather than calling them objects of reference, it may be preferable to refer to them as "location markers". Activity markers Objects are also often used to signify the start of activities. For example, a paint brush signifies an art lesson; a book, a literacy lesson. Again, it may be preferable not to use the term objects of reference in this context, but to call them "activity markers". Like objects of reference, it may be necessary to individualise these: for example, Leanne likes to use a tambourine in music, but Yaqoob prefers maracas. Thus, they may not really understand if everyone is presented with a chime bar beater. In time, activity markers can be used for some children to inform them of the timetable. They can be attached in sequence to a vertical board or placed in horizontally arranged segmented trays. Choosing objects of reference Selecting an object of reference for a particular item, place, person, event, activity or experience is not easy. Remember, an object of reference is an object to which the child attaches a special meaning. It is therefore essential to view things from the individual child's perspective. The object should be something the individual directly experiences and associates with the particular item, place, person, event, activity or experience. Presenting objects of reference There are some simple rules for presenting an object of reference, it must be: the same object every time presented immediately before the item, place, person, event or activity it represents used every time it is needed presented in the same manner every time presented with the same accompanying speech / signing every time. As more objects of reference are introduced, it is essential to consider the contrasts between them: it is not going to help if the child becomes confused by objects of reference that are very similar. Objects of reference in the classroom If at all possible, objects of reference should become a means for the child to express needs and desires, and not just to support understanding. This means that the child must have access to their objects of reference so they can select them when necessary. This can be a major problem for some children, particularly those who also have a motor impairment. For the mobile child, objects of reference can be stored on a section of accessible shelving, on hooks on the wall, or in a box; wherever they are kept, it is essential to adopt the following rules: ensure the child knows where they are kept always return objects of reference to the storage place immediately after use allow the child free access to their objects of reference at all times. For a wheelchair user, it will be preferable, perhaps even necessary, for the objects of reference to be reduced in size, and made more abstract (see below). If this is done, it may be possible for them to be kept in bag attached to the wheel chair, or in a book which is always kept on the tray. Moving on with objects of reference When the child has been using several objects of reference for some time, it may be appropriate (even necessary) to make them more abstract: initially, they could be reduced in size later, part of the object could be used (eg instead of a whole cup to mean "drink", it may be just the cup handle) later still, some objects can be turned into an abstract symbol; e.g. the cup handle could become a printed or tactile semicircle, which, eventually could become a printed letter "c", or the Moon equivalent. 2.5. References This article is only an introduction to objects of reference. For more information, refer to Ockleford, A. (2002) Objects of Reference. London: RNIB. Part 3: Promoting communication in children with complex needs About this part This part gives explores the challenges of promoting communication in children with severe vision impairment and complex needs. Written by Ian Bell, Teacher and Speech and Language Therapist, Ian has considerable experience of children with special needs, including those with severe vision impairment and complex needs, and those with autism. This guide looks at three helpful communication strategies to allow children with vision impairment and complex needs to get the most out of their education. Contents: 3.1. Three helpful Strategies 3.2. Augmenting speech 3.3. Interacting with the child 3.4. Using objects and events 3.5. Summary 3.1. Three helpful strategies Promoting communication in children with severe vision impairment and complex needs is a major challenge. Children in this group vary so widely with regard to their precise disabilities and skills that it is really only possible to provide general principles. Something that works with one child may not work with another. The strategies for promoting communication can be divided into 3 broad categories: 1. augmenting speech 2. interacting with the child 3. using objects and events. 3.2. Augmenting speech Augmenting speech is a major topic. It is mentioned here as it is important to view it alongside interacting with the child and using objects and events, as being one of the three interdependent categories of strategies available to us for promoting communication in children with severe vision impairment and complex needs. 3.3. Interacting with the child In our 'Becoming a sensitive communication partner' guide, written by Caroline Knight, Caroline describes strategies to employ when interacting with children. This section develops the theme of being sensitive by describing strategies in which the emphasis is on what adults do. Many children with severe vision impairment and complex needs are rather passive and lack spontaneity. Yet being spontaneous taking the initiative - is essential for communicating effectively. Caring adults are naturally concerned when a child has few skills, and often feel the need to provide a lot of stimulation to encourage development. Unfortunately, when it comes to communication, this can be counter-productive: the more we stimulate the child, the less the child is free to take the initiative - to be spontaneous. To promote spontaneous communication, we need to back off - we need to "ALLOW": Always Look, Listen, Observe, Wait. Case study Bob is developmentally very young; he has a little vision, being able to see a bright object up to 30cm away on his right; and he has cerebral palsy, and cannot use his hands to manipulate objects. His teacher, Sue, provides a wind-up musical toy for Bob, placing it where he can see it. He smiles and waves his hands while the music is playing, and stops when the music stops. Bob does nothing to communicate that he wants it again. However, Sue interprets Bob's smiling and waving as indicating that he enjoys the toy. She winds it up again and does this several times over a period of a few minutes. But she hasn't ALLOWed Bob to communicate spontaneously. Sue can do so, however, using the ALLOW approach. When the toy stops, instead of winding it up again, Sue looks at Bob, and listens - she observes, and waits. She notices he vocalises quietly and reaches out slightly towards the toy. Sue interprets that as "I want the toy again" and winds it up. After a few days, Bob vocalises louder and reaches better: he is communicating spontaneously. Modelling For children using a symbolic means of expression (eg speech, sign, or a communication aid), modelling is useful. This strategy requires two staff to work together, so its use must be agreed in advance. For example, Afzal asks Sue, her teacher, for help putting on her coat by holding it out to someone. Instead of helping the child herself, Sue involves her assistant, Steve, who is waiting close by. Sue says "OK, Afzal. Ask Steve - say 'Help'." Steve helps Afzal to put her coat on. Sue and Steve also set up other situations in which Afzal needs help, giving them plenty of opportunities to use the modelling strategy. Soon, Afzal spontaneously says "Help" in a variety of situations. 3.4. Using objects and events This section describes strategies in which the emphasis is on the use of objects and events. Sabotage Sabotage is useful with children who use a symbolic means of expression (eg speech, sign, or a communication aid). For example: at snack time, give a child who asks for a drink an empty cup; one who asks for apple some banana; or give an unpeeled banana to a child who cannot peel it; in art, give the child some paper and a paintbrush, but no paint; in music, give the child a drum, but no stick. In each of these situations, ALLOW the child to communicate in some way before intervening. Sabotage can involve causing an unexpected event, such as a stack of bricks falling down. Follow this by ALLOWing the child to comment in some way (for a preverbal child, the comment might be a gesture or vocalisation). Enticing Another strategy for children who have some vision is "enticing". Place a favourite item in view, but just out of reach. In some cases this will mean placing it in a clear plastic container which the child cannot open. Again, ALLOW the child to communicate in some way before intervening. Interrupting Routines can be used to promote spontaneous communication by interrupting them and adopting the ALLOW approach. At first, this should be tried with a really familiar routine. For example, Susie has been to the school office many times; Mike, the administrator, always says "Susie, Hello!" and hands her a cuddly bear. Susie vocalises "ah". Instead of giving Susie the bear, Mike says, "Susie, Hello!" and waits. Susie vocalises "ah", which Mike interprets as a request for the bear and gives it to her. When the child is familiar with routines being interrupted, sabotage can be used. For example, Moses enjoys a rocking boat. He knows the routine: going to the play area, being placed in the rocker, moving his trunk to make the boat rock, and participating in the song "Row, row, row your boat". He joins in by chanting "oh, oh, oh". This routine can be sabotaged by starting another song, and pausing. The pause ALLOWs Moses to chant "oh, oh, oh", communicating which song he wants. Choice There are many opportunities to provide choice. If the child is using a symbolic means of expression, a simple question may be appropriate: "Which instrument do you want?" At an earlier stage you may need to present alternatives: "Which instrument do you want? Drum or tambourine?" Beware of children merely echoing the second option. But, even if you suspect the child has done so, respect their choice. For children without symbolic communication, you may need to demonstrate each option briefly and pause. If the child has no vision, and so cannot choose using eye gaze, you may need to judge their choice by interpreting facial expression, arm movements, or vocalisations. 3.5. Summary These strategies of ALLOWing, modelling, sabotaging, enticing, interrupting and offering choice can be very useful. But their effectiveness relies on them being used by all those who come into contact with the child, and in all the situations the child regularly experiences. Part 4: Becoming a sensitive communication partner About this part This part gives explores how to support a child with complex needs and visual impairment in developing early communication skills. Written by Caroline Knight, Speech and Language Therapist, this guide looks at the impact a vision impairment can have on communication and focuses on techniques and strategies for developing communication skills. Contents: 4.1. Babies, communication and vision 4.2. Communication and vision impairment 4.3. Communication techniques and strategies 4.4. Taking control 4.5. Towards symbolic functioning and speech 4.6. Communicating with a wider circle 4.7. References 4.1. Babies, communication and vision New babies arrive armed with a wide array of behaviours. Initially these can be displayed indiscriminately and unintentionally. Caregivers, however, are drawn in to the infant and typically respond to these behaviours as if communication is taking place. They will give meaning to what is taking place and respond accordingly. An infant that cries is told: "Oh, you are hungry", and given a feed; one that kicks its legs may hear: "You are excited. You like your bath", and is then given the opportunity to experience bath time. "My behaviours affect others" With time, the child realizes that their behaviours are affecting those around them and they start to use the behaviours with the intention of influencing those around them. The child thus guides the caregiver with a combination of looks, movements towards objects, vocalizations etc. Moving on to speech The next development sees the child refine skills and use more systematic and symbolic ways of making their needs known, typically through speech. Importantly, this takes place within the context of the development of shared and joint attention, much of which is dependent on the shared sensory experiences of the infant and caregiver. The interactive nature of communication means that the progress of the child is reliant on access to communication partners. 4.2. Communication and vision impairment The use of vision plays a key role in these interactions in these early stages. In the absence of these key visual elements, the child with vision impairment can struggle to progress with their communication. How does the child know when their caregiver is attending to them? How do they develop shared attention when they have a very limited range of experiences in common with those around them? The context as experienced or perceived by the child with vision impairment and complex needs may not match that of the caregiver who may not be able to or know how to respond appropriately. For example, a sighted child may hear its mother shaking a rattle. The child may then move, look at the rattle and change its facial expression. The mother registers her child's interest and attention and continues to interact with the rattle, watching the baby and commenting on the reactions of the child. By contrast, a child with vision impairment may "still" as they attend to a sound and facial expression may appear passive. The mother interprets these behaviours as a lack of interest and the interaction is not continued. This mismatch results in the child, already disadvantaged by the impact of their disabilities, having access to fewer and poorer communication exchanges on which to build their skills. 4.3. Communication techniques and strategies By adapting and refining our communications, we can support the child in their communication development. The following techniques and strategies have been found to be beneficial when laying down the foundations for communication and language development in children with complex needs and vision impairment. Sharing the moment - multi-sensory interactions Shared and joint attention are fundamental building blocks to a child's development. We need to consider what the child without vision is experiencing. We need to develop other ways of making and maintaining contact to compensate for the lack of eye contact and gaze. Adults should consider the following and use them in their interactions to engage with the child: touch movement vibration rhythm smell place sound - voice, intonation sounds - environmental air currents. Cutting out clutter We need to be aware that stimuli (sound, smell etc) may occur naturally within the child's environment. While it is not possible or useful to provide a sterile environment for a child, we do need to be aware of things competing for the child's attention. They will not be able to filter them out as we do, or they may be overwhelmed and shut down. Creating structure and routine Develop small routines when interacting with the child. In these interactions alert the child by using their name and touch in a consistent manner. Exchanges should include clear signals that show the beginning and the end. Going slowly and noticing responses It cannot be stressed enough that large amounts of time need to be built into these interactions. The pace should be such that it allows the child to process what it is experiencing and to organise a response. The adult also needs time as they will need to look at a variety of often very subtle responses from the whole child. The Affective Communication Assessment in "Communication Before Speech: Development and Assessment" (Coupe, O, Kane, J. and Goldbart, J. (1998) provides an excellent framework for this. It enables the identification of reliable responses or behaviours to events, people or other stimuli and the systematic ways in which a child responds and affects their environment. The authors also give guidance on how to reinforce these communication attempts and facilitate the movement from pre-intentional to intentional communication. Intensive Interaction Another approach, Intensive Interaction, develops pre-speech fundamentals at these early stages of communication development. The non-directive approach is built around interaction sequences that follow the lead of the individual (See www.intensiveinteraction.co.uk). Setting the context It is not just the face-to-face interactions in micro-routines that will promote a child's communication. Clear daily routines should be established so that the child can gradually make sense of what could otherwise be chaotic and fragmented experiences. Making the patterns, routines and sequences of life explicit to the child will increase the feeling of security. The child will be able to understand and learn about his experiences and develop anticipation of events. They will eventually also learn how to manage when things do not go as expected. Using objects and signs The use of object cues and Objects of Reference can be readily incorporated into daily routine to give extra information to the child. By consistently linking an object with an activity the object comes to represent that activity for the child. For example, a child can be given a particular spoon to hold and told "it's time to eat" just before a meal is served. Eventually the child makes the connection and they begin to anticipate their meal on being handed the spoon. Early communication through touch can be extended into on-body signing (see "Learning Together: a creative approach to learning for children with multiple disabilities and a vision impairment" (1992). The authors give clear guidance on creating a learning environment that promotes active exploration and communication. 4.4. Taking control As the child continues to experience successful communication with partners who are sensitive to their needs they will begin to develop intentionality. As the world becomes clearer and more predictable they will be able to realise that they can also have an effect on those around them and will begin to take control. Cause and effect can be explored and practices in many different ways: through work on a resonance board (www.lilliworks.com) in Intensive Interaction sessions making meaningful choices using Objects of Reference coactively signing to gain more of something (or perhaps a more motivating drive) to make something stop through technology such as switches. 4.5. Towards symbolic functioning and speech Symbolic functioning can be developed through various ways. Exploration and experience with objects can lead to the use of Objects of Reference as a means of expressing a choice; signing also provides a shared means of communication. These should be accompanied by speech when used by the adult. As a sensitive communication partner you will adapt your speech to meet the needs of the child: begin with the child's name to alert them position yourself at the child's level make your voice interesting using rhythm and intonation use short clear phrases related to what the child is experiencing support key words (those that the child needs to understand) with relevant objects, signs etc use pauses to give child time to process value the child's turn in the interaction give feedback to the child to show how you are interpreting them. In time the child may use vocalizations in a consistent way that can be interpreted to represent something. It is essential to give the child feedback on your interpretations so that these can be further expanded. 4.6. Communicating with a wider circle As the child grows so will the opportunities for communication with a wider circle. The child will meet new communication partners who will not be tuned in to their idiosyncrasies and particular communication style. Using a Communication Passport One way of passing on what you have found out about the child's communication strengths is through a Communication Passport. These present the child in a positive light and reflect the individuals' personality, their needs and what is important for them. In describing the child's most effective means of communication and how others can best communicate with them, the passport can ensure a consistent approach is taken by all who interact with the child. Through encounters with sensitive communication partners the child will enhance their own communication skills and build their self-esteem. This will assist the children to take on an active role in their own communication development. 4.7. References Coupe, O, Kane, J. and Goldbart, J. (1998). Communication Before Speech - Development and Assessment (2nd edition). London: David Fulton Best, A. (1992) Teaching children with visual impairments. Milton Keynes: OUP Visit www.intensiveinteraction.co.uk Visit www.lilliworks.com Lee, M., MacWilliam, L. (2002) Learning Together. RNIB Routes for Learning www.wales.gov.uk Ockleford, A. (2002) Objects of Reference. London: RNIB. Part 5: Using Touch with children with complex needs About this part This part explores how to reduce potential barriers to learning and participation through touch for children who have multiple disabilities and vision impairment. This guide is written by Professor Mike McLinden and Steve McCall, Senior Lecturer in the Visual Impairment Centre for Teaching and Research (VICTAR) at the School of Education, University of Birmingham. Contents: 5.1. How important is touch? 5.2. Case Study: Rosie and Rafie 5.3. Themes arising from the case study 5.4. Direct contact or less directive approaches? 5.5. Types of touch 5.6. Concluding thoughts 5.7. References 5.8. Further reading 5.1. How important is touch? Vision is a powerful sense for learning and development, as everyone with useful vision for near as well as distance activities knows. So children who do not receive consistent visual information are more reliant on others to structure their learning experiences and help them make sense of the world. In this article we examine the role of touch in learning and development, with a particular focus on children and young people with vision impairment and complex needs. We will explore how potential barriers to learning and participation can be reduced through structuring appropriate teaching and learning experiences. 5.2. Scenario: Rosie and Rafie We have based the article around a real-life scenario situated in a special school for children with learning difficulties. We will draw on the scenario to explore key themes relating to learning through touch. The location is a day school for children with a range of learning difficulties. Within the school, there are six children who are supported by a visiting qualified teacher of children with vision impairment (QTVI). The focus of the scenario is on two of the children with a visual impairment, Rosie and Rafie. The lesson: "Great Explorers" It is 9.30am and the first lesson is about to begin for nine year old Rosie and ten year old Rafie. Although the lesson is called "Great Explorers", the focus is not on traditional explorers who have discovered new and exciting lands, but on Rosie and Rafie, who are each provided with carefully crafted opportunities to become a "great explorer". The session has been planned through close liaison between the QTVI, the class teacher and the class teaching assistant (TA), Dave, who is supporting the two children in the session this morning. Dave introduces himself to each child. He shakes the two metal bangles on his wrist and asks each child if they want to reach out to feel them. The bangles are used as Dave's personal signifier and each child in turn is provided with an opportunity to feel around them. Treasure chests Dave tells the children in turn that he will be putting their "exploring tray" and their "treasure chest" onto their respective wheelchair trays. The treasure chest contains a number of hand-held objects that the children have experienced before. These include a digital talking watch, a metal serving spoon, a sponge ball and a set of keys on a key ring. Each chest also contains a novel object introduced as "new treasure": for Rosie, this is a hair slide; for Rafie, it's a small leather purse with a Velcro opening. Dave sits alongside the children and carefully supports each child in feeling the contours of the empty tray and the outside of their treasure chest. He then invites the children to select some treasure from their chest, jointly exploring the object's distinctive features and placing it onto the tray for further manipulation. Playing with the treasure Dave tells the children that he will sit quietly alongside them while they play with their treasure, only talking to show them something really interesting about the object, or to help them locate another object from their chest. He makes sure he is positioned so that his right arm gently touches Rafie's left side to provide a reassuring presence, and observes the children carefully, noting down how each child explores the distinctive features of the selected object. The session continues for approximately 20 minutes. At the end, each child is asked to select one piece of treasure that they have enjoyed playing with and to pass it directly to the other child. Rosie smiles and passes the hair slide to Rafie to hold. With support from Dave, Rafie is able to open and close the hair slide and places it onto Dave's hair. Dave then places the hair slide on to Rafie's hair. Rafie begins to laugh. Rafie then feels within the contours of his own tray, seeks out the talking watch and hands this to Rosie. Rosie takes the watch and with support from Dave places it onto her wrist. She pushes a button and, on hearing the clock telling the time, begins to laugh. Finally, Dave says it's nearly time to end the lesson, and supports the children in returning the objects from their tray to their treasure chest. Each child is then encouraged to check that their tray is empty and to close their treasure chest. Notes on the scenario There are three elements of particular interest here: the care with which the TA introduced objects to the children how he ensured appropriate time was provided for each child to locate and explore the object the careful planning that had been put into the design of the session to ensure it was appropriate for each child's individual needs, with particular attention to the learning environment. 5.3. Themes arising from the scenario We will now consider this scenario in further detail, drawing on a broad framework which highlights the significance of a child's adult partners when supporting the child's learning experiences through touch (McLinden and McCall, 2002). Within this framework we have identified four broad themes, which we expand with reference to the scenario. 1) How does each child receive information through the senses? The learning experiences of a child who has a vision impairment and complex needs will incorporate a range of sensory information, some of which will be distorted in quality and/or quantity. In order to work effectively with the child, the adult partners need to know and understand a child's level of sensory function: how the child receives, interprets and consequently acts upon different types of sensory information during a given task. Different sensory experiences are important in learning and development. The QTVI who supports the school has carried out a detailed assessment of the functional vision of all the children with a visual impairment in the school. The findings of the assessment are used in planning the child's curriculum. How do Rosie and Rafie use touch? Rosie: The vision assessment revealed that, although Rosie is registered blind, she has some useful vision in certain environments (for example, she can see bright lights in a darkened room). She also occasionally brings an object she is particularly interested in close to her eyes for visual inspection. While she has limited independent mobility, Rosie has good fine motor control in her hands and fingers, and is usually very keen to explore objects that are presented to her on her tray. Rafie: Rafie also has some vision, although it is not clear how much use he can make of this for everyday tasks. He does not appear interested in using his vision to view faces or objects, but he does appear to enjoy watching the changing colours of the fibre optic lights in the multisensory room. Rafie is hemiplegic and is unable to manipulate small objects independently with both hands. It is not clear how much enjoyment he gets from using touch to find out about his world, and he requires frequent reassurance and support from an adult partner to assist and encourage him. Responding to each child's needs This type of information was very useful to the class teacher in planning the session. It highlights that, while children may have common needs created by multiple disabilities that include vision impairment, the particular approaches need to be structured to ensure they meet each child's unique blend of needs. (Examples of common needs in this scenario include the need for well-defined contours within which the child can independently manipulate an object; the time required to allow a child to process the information through touch; alerting the child to what is going to be happening next prior to the event taking place, etc.) 2) Distant and close senses In considering how a child processes and acts upon sensory information, a broad distinction can be made between information received from a distance (for example through vision and hearing), and information received close to the body (for example through touch and taste). In the absence of consistent information through the distant senses, the information received through the close senses increases in significance in a child's learning experiences. This distinction between distant and close senses is commonly made in the literature about child development. Is this a jar of honey? Vision is often referred to as an "integrating" or "co-ordinating" sense. Imagine reaching into a dark cupboard to find a jar of honey. You may have an overall impression of the object in your hand through touch, as well as information about some of its features (eg the fact that it is a jar rather than a pot). However, without additional supporting information (eg smell) you may struggle to make sense of what the object is. If you have useful vision and it is light enough, you would be tempted to bring the object towards your eyes to check if it is indeed a jar of honey. If you do not have useful vision, or are unable to see the object, you may draw upon additional close senses to help you. In this case, your sense of smell, or indeed taste, would be very useful! 3) Sensory impairment and knowledge acquisition For a child who is more reliant on information received through the close senses, their learning experiences can provide imprecise information about the world if they are not mediated at a level appropriate to the child's needs. This can have an important bearing on the child's knowledge and understanding of the world at critical stages in early development. The child's adult partners need to appreciate the unique ways in which each of the senses function. "It's time to go now" Imagine how you would respond to somebody suddenly placing a hand onto your right shoulder while you are sitting down and saying: "Hello there, its time to go now". You might want to turn around to see who this hand (or voice) belongs to. However, if you have a severe vision impairment, you will need to rely on your other senses. This might include touching the person's hand (or other part of the person's body), asking the person to identify themselves, or waiting until he or she speaks further in an attempt to identify the voice. What if you also have limited gross and fine motor abilities which means you are confined to a wheelchair, unable to move your arms independently and have very limited speech? How much more of a challenge is it to know where you are being asked to go, and who with? 4) Good adult support The child's adult partner will need to have knowledge and understanding of his or her role in mediating the child's learning experiences through each of the senses to ensure that these are appropriate to the child's individual needs. We have already noted the careful planning that had been put into the session described in the scenario. This involved close liaison between the QTVI, class teacher and TA prior to the session to ensure it had a clear focus. The session allowed the children to find out about the world in a safe and structured environment that was both engaging as well as fun. 5.4. Direct contact or less directive approaches? Is direct contact always needed? It is all too easy to think that effective learning through touch for a child with a severe vision impairment can only occur through direct adult contact with the child, for example introducing an object to a child using 'handsover-hands' guiding strategies (McLinden and McCall, 2002). Sometimes, a less directive approach can also work: for example, giving a child the chance to examine an object without always being physically guided by the adult. In short, it is important to carefully consider approaches to learning which include both 'hands-on' as well as 'hands-off' strategies (Hodges and McLinden, 2004). 5.5. Types of touch Despite an increased interest in the role of touch, we actually know very little about how touch is used with the classroom environment with individual children. However, there is evidence from a small scale study on a child with a vision impairment and complex needs in a special school (Hodges and McLinden, 2004). We can use a number of the key points developed from this study to describe the use of touch for each of the two children in our scenario (Rosie and Rafie). These nine key points may also be of use in helping practitioners who work with children with MDVI to assess their own practice. 1) Purposeful touch Within the session, touch always has a clear purpose, relating to access to the curriculum, communication with the children or management of tasks (for example, Dave supports Rosie in placing the watch onto her wrist). 2) Cued touch The children are not surprised by an unexpected touch, because touch interactions are signalled through verbal cues. The touch is also accompanied by additional cues, so that it was part of a sequence of events which help each child to make sense of the experiences. For example, Dave draws Rafie's attention to distinctive features of the watch while he manipulates it in his tray. 3) Social touch Touch is not only used to find out about objects and sensory experiences. "Social" touch is also used during the session: for example, for the TA to introduce himself. Dave also gives the children structured opportunities to make contact with each other. 4) Independent touch Although "hand over hand" guiding strategies are used (for example, to draw Rafie's attention to particular features of an object) opportunities are also provided for him to feel objects independently without adult support. Additional guiding strategies include "hand under hand", where the adult's hand is underneath the child's hand. 5) Meaningful touch The interactions involving touch are integrated into a meaningful session, and careful thought is given to the objects that are selected. For example, the talking watch for example allowed for engaging peer interaction at the end of the session. 6) Consistent touch There is a high level of consistency in the approaches used by different adults in the school to support each child's learning experiences. The TA uses a carefully crafted "script" that outlines the particular approach to be adopted with each of the children when interacting with them through touch. 7) Informative touch Objects are not placed into the children's hands without a supporting context. Touch is used to provide the children with information about a variety of events, including the layout of the tray in front of them and the people around them. This information is also presented as part of whole events, and is included as part of sequences which each child is learning to understand (ie the beginning and ending of a particular lesson). 8) Communicative touch As well as being used to find out information about the world, touch is used for communicative purposes. For example, Dave sits alongside Rafie, observing him play, with his right arm gently placed against Rafie's left side to provide a reassuring presence. 9) Invited and acceptable touch Rather than having an object imposed upon them, each child is invited to join with Dave in exploring interesting materials from their treasure chest. When changes are made to their physical position, or when Dave alerts them to a distinctive feature, appropriate warning is given. 5.6. Concluding thoughts Within the wide range of educational needs created through multiple disabilities, the role of touch in a child's learning and development can easily be neglected. Practitioners and researchers are only now beginning to appreciate the complexities, and subtleties, of touch. Children with a vision impairment and complex needs, need varying levels of support from adults throughout their education. Therefore, it may not be appropriate to focus exclusively on a child's use of touch. A significant feature of children who have a vision impairment and complex needs is their increased dependency on other people to structure their learning experiences. This includes what and who they interact with, the nature of their interactions, where the interaction takes place, and the duration of any given interaction (McLinden and McCall 2002). Becoming more engaged through touch through close liaison between the different professionals and with careful planning and input, Rosie and Rafie were actively engaged throughout the session. Both children were alerted to different touch experiences, allowed to withdraw their hands as appropriate, involved in meaningful tasks and motivated by them. This approach means that they should increasingly welcome tactual experiences and information. That will help them to become more actively engaged in other classroom experiences - and in turn, to become increasingly great explorers in their own time. 5.7. References McLinden M and McCall S (2002). "Learning Through Touch". David Fulton: London Hodges, L., McLinden, M. (2004). "Hands on - hands off. Exploring the role of touch in the learning experiences of a child with severe learning difficulties and visual impairment". SLD Experience, Spring, 38, 20-24. 5.8. Further reading Project Salute is a good starting point for information and resources. The project's subtitle is "Successful Adaptations for Learning to Use Touch Effectively". Visit: www.projectsalute.net For more information. A range of useful resources is listed in the glossary of "Learning Through Touch" (see References, above). 6: Further guides The full Complex Needs series of guides includes: Special Schools and Colleges in the UK Functional Vision and Hearing Assessments Communication: Complex needs Working with complex needs in the classroom The Staff team Understanding complex needs In addition, you may also be interested in the following series of guides, all of which are relevant to children, young people and families: Supporting Early Years Education series Removing barriers to learning series Complex needs series Further and Higher education series We also produce a Teaching National Curriculum Subjects guide, and a number of stand-alone guides, on a range of topics. Please contact us to find out what we have available. All these guides can be found in electronic form at rnib.org.uk/educationprofessionals For print, braille, large print or audio, please contact the RNIB Children, Young people and Families (CYPF) Team at cypf@rnib.org.uk For further information about RNIB Royal National Institute of Blind People (RNIB), and its associate charity Action for Blind People, provide a range of services to support children with visual impairment, their families and the professionals who work with them. RNIB Helpline can refer you to specialists for further advice and guidance relating to your situation. RNIB Helpline can also help you by providing information and advice on a range of topics, such as eye health, the latest products, leisure opportunities, benefits advice and emotional support. Call the Helpline team on 0303 123 9999 or email helpline@rnib.org.uk If you would like regular information to help your work with children who have vision impairment, why not subscribe to "Insight", RNIB's magazine for all who live or work with children and young people with VI. Information Disclaimer Effective Practice Guides provide general information and ideas for consideration when working with children who have a visual impairment (and complex needs). All information provided is from the personal perspective of the author of each guide and as such, RNIB will not accept liability for any loss or damage or inconvenience arising as a consequence of the use of or the inability to use any information within this guide. Readers who use this guide and rely on any information do so at their own risk. All activities should be done with the full knowledge of the medical condition of the child and with guidance from the QTVI and other professionals involved with the child. RNIB does not represent or warrant that the information accessible via the website, including Effective Practice Guidance is accurate, complete or up to date. Guide updated May 2014