Tone, Diction and Syntax Handout

advertisement

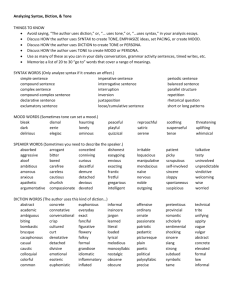

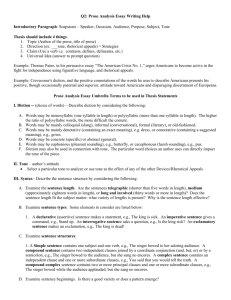

KEEP THIS HANDOUT FOREVER, OR LONGER. Tone, Diction, and Syntax TONE: the writer or speaker’s attitude toward the subject, audience, or events of the text. Word choice (diction), details, imagery, and sentence structure (syntax) all contribute to the understanding of tone. So…tone is the result of other literary choices made by the author. Keep in mind that all texts have tone. You can’t just say, “The paragraph has tone.” You have to specify or qualify the tone. “The author’s angry tone in the third paragraph shows that she has not forgiven her brother.” Tone vocabulary: angry sad fanciful upset joking giddy proud seductive understanding pitiful restrained provocative sweet irreverent benevolent vexed detached zealous nostalgic confused sentimental urgent bored happy mocking humorous weary shocked candid hollow sharp complimentary poignant dramatic horrified dreamy afraid childish sarcastic mournful cold silly sympathetic didactic somber condescending apologetic objective contemptuous ecstatic Activities: Use a thesaurus to find synonyms for the following words. Be ready to discuss the attitude or tone implied by each synonym. laugh old fat self-confident house king In five minutes, list as many synonyms as you know for the following: 1 Funny Happy Sad Angry DICTION: The connotation or associations of word choice. Just as with tone, all works have diction. Again, you must specify or qualify the diction. Instead of “The author’s diction was interesting, “ say, “Salinger’s slang-filled, often profane diction in The Catcher in the Rye captures the voice of its teenage narrator.” Diction or language vocabulary: jargon euphemistic poetic pedantic scholarly pretentious sensuous idiomatic informal precise cultured esoteric symbolic homespun simple trite obscure emotional obtuse detached bombastic vulgar slang colloquial picturesque plain literal concrete moralistic insipid formal learned connotative provincial figurative Examples: When I told Dad I screwed up on the exam, he blew his top. (Colloquial, figurative) I had him on the ropes in the fourth and if one of my short rights had connected, he’d have gone down for the count. (Jargon) Activity: Describe the diction of each of the following sentences: 1. We regret to inform you of the forthcoming foreclosure of your mortgage. Our previous attempts at communication were heretofore unacknowledged. 2. Come back soon, y’all! 3. Beyond the verdant valleys and craggy peaks, a small house was nestled in a wood along a winding blue river. 2 SYNTAX: Sentence structure, including sentence length and pattern. As with diction and tone, you need to qualify or specify the syntax. Don’t just say, “The author uses syntax to show his views of nature.” Better: “The author uses long, compound-complex sentences to show his overwhelming love of nature, specifically the forest where he goes nutting.” Sentence length: short, medium, long, choppy, flowing, fragmented. Some types of sentence patterns: a. Declarative: statement Imperative: command Interrogative: question Exclamatory: exclamation The queen is sick. Stand up. Is the queen sick? The queen is dead! b. Rhetorical question: expects no answer; used to draw attention to an idea. Sometimes expresses humor or sarcasm. Have you ever wondered why the sky is blue? Did you have trouble finding the classroom this morning? “Was it cowardice, that I dared not kill him? / Was it perversity, that I longed to talk to him?” (D.H. Lawrence, “Snake.”) c. Simple: one subject and one verb The queen is sick. Compound: two independent clauses joined by a coordinating conjunction (FANBOYS: for, and, nor, but, or, yet, so) or semicolon. The queen is sick; her husband remains healthy. The queen is sick, but her husband remains healthy. Complex: an independent clause and one or more subordinate or dependent clauses. You said that the queen is sick. 3 Compound-complex: two or more independent clauses and one or more subordinate clauses. You said that the queen is sick; I heard that she’s getting better. You said that the queen is sick, but I heard that she’s getting better. More on dependent/subordinate and independent clauses: Independent Clause An independent clause is a group of words that contains a subject and verb and expresses a complete thought. An independent clause is a sentence. Jim studied in the Sweet Shop for his chemistry quiz. Dependent Clause A dependent clause is a group of words that contains a subject and verb but does not express a complete thought. A dependent clause cannot be a sentence. Often a dependent clause is marked by a dependent marker word. When Jim studied in the Sweet Shop for his chemistry quiz . . . (What happened when he studied? The thought is incomplete.) Dependent Marker Word A dependent marker word is a word added to the beginning of an independent clause that makes it into a dependent clause. When Jim studied in the Sweet Shop for his chemistry quiz, it was very noisy. Some common dependent markers are: after, although, as, as if, because, before, even if, even though, if, in order to, since, though, unless, until, whatever, when, whenever, whether, and while. Source: Purdue Online Writing Lab. "Purdue OWL: Independent and Dependent Clauses." Welcome to the Purdue University Online Writing Lab (OWL). Web. 09 Feb. 2011. <http://owl.english.purdue.edu/owl/resource/598/1/>. d. Loose: sentence with independent clause first, followed by dependent or subordinate clauses. It makes sense if brought to a close before the actual ending The queen is sick with a mild stomachache brought on by eating raw oysters. Periodic: Dependent or subordinate clauses first, followed by independent clauses. This type makes complete sense only when end of sentence is reached, and typically the end of the sentence is dramatic. 4 After eating raw oysters, the queen became ill. More on loose and periodic sentences: "Although loose sentences are less dramatic than periodic sentences, they too can be crafted into rhythmically pleasing structures. John F. Kennedy, for example, began his 1961 inaugural address with a loose sentence: 'We observe today not a victory of party but a celebration of freedom, symbolizing an end as well as a beginning, signifying renewal as well as change.'" (Stephen Wilbers, Keys to Great Writing. Writer's Digest Books, 2000) "A loose sentence makes its major point at the beginning and then adds subordinate phrases and clauses that develop or modify the point. A loose sentence could end at one or more points before it actually does, as the periods in brackets illustrate in the following example: It went up[.], a great ball of fire about a mile in diameter[.], an elemental force freed from its bonds[.] after being chained for billions of years. A periodic sentence delays its main idea until the end by presenting modifiers or subordinate ideas first, thus holding the readers' interest until the end." (Gerald J. Alred, Charles T. Brusaw, and Walter E. Oliu, The Business Writer's Companion. Macmillan, 2007) Source: Nordquist, Richard. "Loose Sentence - Definition and Examples of Loose Sentences." Grammar and Composition - Homepage of About Grammar and Composition. Web. 09 Feb. 2011. <http://grammar.about.com/od/il/g/loosenterm.htm>. e. Natural order: subject precedes predicate. Oranges grow in California. Inverted order, inversion, or Yodaspeak: predicate precedes subject. In California grow oranges. Confident am I that you will make the right choice, Anakin. f. Juxtaposition: normally unassociated ideas, words, and phrases placed next to each other for significant effect, often surprising or witty. The apparition of these faces in the crowd; Petals on a wet, black bough (Ezra Pound, “In the Station of the Metro) g. Balanced: The phrases or clauses balance each other by virtue of their likeness in structure, meaning, and/or length. Usually longer. Blessed are they that mourn: for they shall be comforted. Blessed are the meek: for they shall inherit the earth. (The Beatitudes) 5 h. Parallelism: similar elements are expressed in similar form, often in a list. The inherent vice of capitalism is the unequal sharing of blessings; the inherent virtue of socialism is the equal sharing of miseries. (Winston Churchill) i. Repetition: Repeating words or phrases to enhance rhythm and create emphasis. Government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth. (Abraham Lincoln, Gettysburg Address) (Syntax portion adapted in part from an anonymous teacher’s adaptation from A Guide for English Vertical Teams, The College Board.) 6 DIDLS: THE TONE ACRONYM DICTION The connotation or associations of word choice. Different words for the same thing often suggest different attitudes toward that thing: consider happy vs. content vs. ecstatic. +IMAGERY Vivid appeals to reader’s understanding through the five senses. The images chosen suggest the speaker’s attitude. In our classroom, I could choose to focus on the peculiar odor of teenagers or the colorful, inspiring posters that fill the walls. +DETAILS Facts that are included or omitted. If a narrator witnesses a horrible sight and withholds the gory details, his attitude would be different than a narrator who focuses mostly on the gory details. Compare CNN vs. The Daily Show vs. People magazine +LANGUAGE The overall use of language such as formal, colloquial, clinical, or jargon. An ambassador speaks differently from Holden Caulfield who talks differently from a doctor who talks differently from a cop. The type of overall language used tells us something about the speaker’s attitude. +SYNTAX The sentence order, length, and structure. Long, flowing sentences give a different feeling than short, choppy ones. If the narrator writes in fragments or awkward sentences, we might think he is uneducated. Long flowing sentences might suggest sophistication or the conventions of a particular time. 7 These elements combine to create TONE. 8