AP Period 2 Part 2: World Religions

advertisement

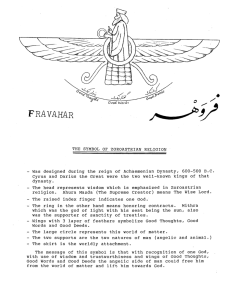

AP Period 2 Part 2: World Religions Overview/Review Shintoism The name of this religion is the Chinese translation of the Japanese “Kami no Michi”, meaning “The way of the Gods”. Shintoism is the native religion of Japan. The origins of this religion are obscure. The essence of this religion is respect for the powers that be, called Kami. A Kami may be anything that evokes a sense of reverence, be it some force in nature, such as Mount Fuji, a god, or even some historical person. The Kami par excellence in Shinto is the Emperor himself. Japan is filled with shrines to these Kami and there is a diversity in the manner in which they are to be approached. The sacred scriptures of Shinto are the Kojike (Chronicle of Ancient Events) and the Nihongi (Chronicles of Japan). These two collections of writings, compiled respectively in 712 CE and 720 CE, trace Shintoism to the beginning of time. The Kojiki outlines the history of Japan from creation to about 650 CE. The Nihongi covers the same time period, only with greater historical accuracy. They tell that the Japanese islands were the first divine creation and the Emperor a literal descendant to earth from the sun-goddess of heaven. Japan has been well noted for its openness to other religions, particularly Buddhism and Confucianism, and various forms of Christianity. These religions have been allowed to thrive in Japan as long as they have not threatened the authority of the Emperor and the concept of the uniqueness of the Japanese people. Contrast them: Daoism and Confucianism Though Daoism and Confucianism shared a core belief in the Dao, or “the Way”, they diverged in how each understood how the Dao manifested itself in the world. While Confucianism is concerned with creating an orderly society, Daoism is concerned with helping people live in harmony with nature and find internal peace. Confucianism encourages active relationships and a very active government as a fundamentally good force in the world; Daoism encourages a simple, passive existence, and little government interference with this pursuit. Despite these differences, many Chinese found them compatible, hence practiced both simultaneously, They used Confucianism to guide them in their relationships and Daoism to guide them in their private meditations. Compare them: Confucianism, Hinduism, and Judaism At first glance, these three belief systems seem very different from one another. After all, Confucianism isn’t really a religion; Hinduism is polytheistic; and Judaism is monotheistic. But they are similar in that they are all closely tied to the culture in which they are practiced; and therefore are not part of the sweeping, evangelical movements that seek to convert the rest of the world. Each not only arose out of a specific culture, but was used to sustain that culture. Contrast them: Legalism and Confucianism Although both Legalism and Confucianism are social belief systems, not religions, and both are intended to lead to an orderly society, their approaches are directly opposed. Confucianism relies on the fundamental goodness of human beings, whereas Legalism presupposes that people are fundamentally evil. Therefore, Confucianism casts everything in terms of corresponding responsibilities, whereas Legalism casts everything in terms of strict lays and harsh punishments. The Han successfully blended the best of both philosophies to organize their dynasty. Classical Greece: Search for Rational Order The classical Greeks did not create an enduring religious tradition. Intellectuals abandoned myths and replaced the multitude of gods/goddesses with the belief that the world is a physical reality with natural laws. They believed that humans can understand these laws and that reason can create a system for ethical life, Sometimes called “the Greek way of knowing”, rational thinking was at its height between 600—300 BC. A key element was the way questions were asked and answered using argument, logic and the questioning of conventional wisdom/authority. Socrates (469-399BCE) is the most famous ‘philosopher’ of this time as he constantly questioned assumptions. This, of course, lead to conflicts with Athenian authorities who eventually accused him of ‘corrupting the youth’. He was executed through the drinking of poison. These earliest of classical Greek thinkers applied rational questioning to nature and eventually applied this to medicine. One application of Greek rationalism lead to a different understanding of human behavior. For example, the historian Herodotus questioned why the Greeks and Persians fought and Plato wrote a book, The Republic, based on his design for a good society. His idea for the best type of government called for a ‘philosopher king’ who would use logic and rationality in his rule. AP Odds and Ends about religions Most of the beliefs systems created or strengthened (codified) in period 2 have impacted world history all the way to the present day. Most have had schisms (divisions) resulting in a variety of subgroups and sects. The test writers will focus more on the overall religion than on particular sects and ways of worship. Don’t focus only on the theological or philosophical basis of each belief, but also on the impact they had on social, political, cultural and even military developments. Pay attention to where each belief started and where and who it spread. As merchants and warriors moved, so did their religious beliefs. Focus on those cultures that frequently interacted with each other. Belief Systems A. Polytheism/animism/Shintoism B. Confucianism/Daoism/Legalism C. Hinduism/Buddhism D. Zoroastrianism * E. Philosophies of Greece F. Judaism/Christianity *See additional handout **note: Islam did not come onto the scene until about 600CE so it will be emphasized in Period 3 Zoroastrianism During the glory years of the powerful Persian Empire, a new religion arose to challenge the polytheism of earlier times. Tradition dates its Persian prophet, Zarathustra (Zoroaster to the Greeks), to the sixth or seventh century BCE, although some scholars place him hundreds of years earlier. Whenever he actually lived, his ideas took hold in Persia and received a degree of state support during the Achaemenid dynasty (558-330 BCE). Appalled by the endemic violence of recurring cattle raids, Zarathustra recast the traditional Persian polytheism into a vision of a single unique god, Ahura Mazda, who ruled the world and was the source of all truth, light, and goodness. This benevolent deity was engaged in a cosmic struggle with the forces of evil, embodied in an equivalent supernatural figure, Angra Mainyu. Ultimately this struggle would be decided in favor of Ahura Mazda, aided by the arrival of a final savior who would restore the world to its earlier purity and peace. At a day of judgment, those who had aligned with Ahura Mazda would be granted new resurrected bodies and rewarded with eternal life in Paradise. Those who had sided with evil and the ‘Lie” were condemned to everlasting punishment. Zoroastrian teaching thus placed great emphasis on the free will of humankind and the necessity for each individual to choose between good and evil. The Zoroastrian faith achieved widespread support within the Persian heartland, although it also found adherents in other parts of the empire, such as Egypt, Mesopotamia and Anatolia. Because it never became an active missionary religion it did not spread widely beyond the region. Alexander the Great’s invasion of the Persian Empire and the subsequent Greek-ruled Seleucid dynasty (330—155 BCE) were disastrous for Zoroastrianism, as temples were plundered, priests slaughtered and sacred writings burned. But the new faith manage to survive this onslaught and flourished again during the Parthian (247 BCE –224 CE) and Sassanid (224—651 CE) dynasties. It was the arrival of Islam and an Arab empire that occasioned the final decline of Zoroastrianism in Persia, although a few believers fled to India, where they became known as Parsis (Persians). The Parsis have continued their faith into present times. Like Buddhism, the Zoroastrian faith vanished from its place of origin, but unlike Buddhism, it did not spread beyond Persia in a recognizable form. Some elements of Zoroastrian belief system, however, did become incorporated into other religious traditions. The presence of many Jews in the Persian Empire meant that they surely became aware of Zoroastrian ideas. Zoroaster (628 BCE—551 CE) The prophet who founded the religion of Zoroastrianism, is said to have seen visions, founded a religion, converted a king and influenced the spiritual life of people for centuries. Unfortunately, little more is known about his life. He lived in ancient northwestern Persia, in what is today northeastern Iran. When he lived is less certain. Tradition teaches that he was born about 600 BC however, some scholars believed he actually lived much earlier (1400 BCE – 100BCE) Some speculate that Zoroaster’s name may mean “camel herder’ and perhaps sheds some light on his origins. He is believed to have left his home at an early age in search of spiritual truths. At about the age of 30, he is reported to have had the first in a series of revelations or visions. He is said to have spoken with Vohu Manah, who represents the “Good Mind.” His soul was led to see Ahur Mazda, the god who led the forces of good in the universe. Out of this developed a religion that recognized this force of good in a struggle with the forces of evil. Zoroaster’s attempts to spread the word near his home failed so he moved east to the kingdom of Chorasmia, an area east of the Aral Sea. It was there that he converted King Vishtaspa to his beliefs. For the rest of his life Zoroaster enjoyed the friendship and protection of the king.