VI B - Zemirot biographies

advertisement

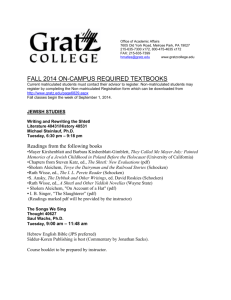

Rg 25-01-04 Fascinating Biographies behind the Zemirot: The Greatest Poets of the Golden Age of Medieval Jewry and their Personal Journeys Table of Contents Chart of Medieval Jewish Poets and Maps Introduction The Ideal Poet of Spain Dunash Ben Labrat, his Wife and his Teacher- Dror Yikra Rabbi Yehuda Halevi – Yom Shabbaton Leaving the Land of the Golden Age for the Dream of Jerusalem Rabbi Avraham ibn Ezra – Tzamah Nafshi; Ki Eshm’ra Shabbat The Wandering Poet, Philosopher, Translator, Biblical Commentator, Grammarian, Mathematician and Astrologer Par Excellence The Jewish Astrologer: Saturn and Saturday Rabbi Yitzchak HaARI Rabbi Yisrael Najara - Ya Ribon Elazar Azikri – The Mystical Diarist of Yedid Nefesh and his Holy Convenant 1 Medieval Hebrew Poets Chart Early Poets (5th –7th century, Eretz Yisrael) Yosi ben Yosi Yannai Elazar HaKalir Moslem Golden Age (10th- -12th Century, Spain) Saadia Gaon (10th, Baghdad) Dunash ben Labrat (10th , Baghdad then Cordoba) – Dror Yikra Menachem ben Saruq (10th Cordoba) Shmuel HaNagid (10th , Granada) Shlomo ibn Gabirol (11th , 1020-1057) Moshe ibn Ezra (12th, Granada) Yehuda Halevi (12th Toledo, then Eretz Yisrael) - Yom Shabbaton Avraham ibn Ezra (12th , Granada, Italy, France, and England) - Ki Eshm’ra Shabbat; Ki Eshm’ra Shabbat Ashkenazi Piyyut in France and Germany Rabbi Menachem ben Makhir of Ratisbonne (11th C.)- Ma Yedidut Baruch of Mainz (12th C.) – Baruch Eil Elyon Moshe (unknown dates before 16th century) – Menucha v’Simcha Kabbalist Poets (16th Century, Safed, Eretz Yisrael) Yitzchak Chandali - Yom Zeh L’Yisrael Yitzchak Luria HaARI Shlomo Alkabetz – L’kha Dodi Yisrael Najara - Ya Ribon Elazar Azikri - Yedid Nefesh Shalom Shabazi (Yemen, 17 th C.) Maps of world powers and languages and religions and migrations 2 Introduction To sing through the traditional medieval Zemirot is to embark on a journey through out Europe meeting some of the most personally colorful as well as most creative artistic minds of Jewry. The time span is from the tenth to the sixteen century. The geographical spread is from Bagdad to Cordoba and north to Germany. But the cultural variety is even greater as we encompass Moslem Spain with supremely cultured aristocrats and courtiers and then to Ashkenazi Western Christian Europe with little entrée to general culture and then to the Turkish Ottoman Empire with strong Kabbalist influences as well as popular vernacular love songs. With the help of the more exceptional biographies and photographs of the more beautiful cities that have preserved some of the medieval ambience we invite you to our thumbnail tour of the people and the places behind of the Zemirot. (By contrast, the tunes we sing however do not preserve the medieval European legacy but rather reveal the vagaries of European, Hassidic and now American and Israeli popular music). The Ideal Poet of Spain In the 19th-20th century the image of the artist is typically a bohemian rebel against the establishment, a nonconformist driven by inner passions released from the rational demands of society. A contemporary poet would never want to be commercialized or put in a situation of needing to flatter his consumers. Innovation – not tradition or ritual – inspires the literary genius’s creativity. However the social ideal of the Hebrew poet of Moslem Spain, as described by the great poet Moshe ibn Ezra, was quite different. These highly educated, scholarly poets, though usually also rabbis and often physicians were nevertheless dependent on the financial and political support of their aristocratic patrons. Their poems were performed in the court in beautiful salons and manicured gardens and dedicated to their benefactors. Yet they maintained a sense of their own calling, both ethically and artistically. Ethically they tried to live as aristocrats of the soul – restrained, noble, affable and sociable, welldressed and generous, true to their friends and truth tellers even when praising others – and socially they sought to maintain tradition and show concern for their people as well as for their upper class compatriots. From the Moslem Spanish court, these Hebrew poets absorbed the values of elegance and beauty as well as the importance of expressing private emotions regarding love, friendship and earthly pleasures. They integrated these aspects into their secular and their sacred poetry. In their sacred poetry they achieved more freedom of self-expression in which they could praise God without fearing that their flattery would be false and servile. Their poems became a permanent feature of the synagogue liturgy and turned services into a welcome arena for literary creativity in the service of the highest Spirit. 3 Dunash ben Labrat (North Africa, Babylonia and Spain, 10th century, 920990) Dunash ben Labrat (whose Hebrew name was Adonim Levi) who inaugurated the Golden Age of Hebrew poetry in Cordoba in Moslem Spain. He was born in North Africa and then studied in Baghdad before reaching Spain at auspicious time. The Golden Age of Moslem Spain gave us Dror Yikra by Dunash ben Labrat in the tenth century and later in the twelfth century Yehuda Halevi’s Yom Shabbaton and his friend and in-law Avraham ibn Ezra’s Ki Eshmira Shabbat and Tzama Nafshi. Even before Dunash arrived, the 10th century in Spain boasted aristocratic court Jews well-versed in Hebrew grammar and patrons of original Hebrew poets reviving Biblical Hebrew in their works. However he brought with him a new model for Hebrew poetry based on outstanding Arabic poetry of the era and he started the greatest and bitterest struggle in Jewish history over Hebrew grammar. Dunash was a student of Saadia Gaon (whose title “Gaon” means “the pride” of the great yeshiva). Saadia was the official leader of the rabbinic yeshivot, the head of the high court of Babylonia and thereby the highest legal authority of all the Jewry under Moslem rule. He resided in the Babylonian capital Baghdad, home of the Caliphate that ruled the vast Arab world from North Africa to India. Dunash’s teacher was not merely an exceptional Talmudist, an academic rabbi, but a fearless political leader and intellectual innovator. Saadiah Gaon (882-942) was a new style of rabbi never known before and he was the cultural Leonardo da Vinci of his era. Born in Egypt, he studied with the great Hebrew linguists, masters of the Masoretic text of the Bible in Tiberias, where he also learned the tradition of Hebrew poetry (Yosi, Yanai etc). Then he went on to Babylonia, political and cultural capital of the Arab empire where despite his outsider status as one coming from the provinces, he was appointed the “gaon”- head of the Yeshiva of Pumpedita and in effect the head of the Jewish Supreme Court of all Moslem lands. An outspoken man of principle, Saadiah confronted the moneyed-head of the Jewish community, the Resh Galuta, and refused to bend the law to serve mere political interests. In every field Saadiah set the standard taking his orientation from the cosmopolitan intellectual elite of the Moslem empire. He invented Rabbinic Jewish philosophy and based it on his dialogues with the great rationalist Moslem religious philosophers of his era. He actually wrote the first Jewish book in the modern sense – original works, not compilations, with introductions, titles and subtitles, and a logical progression speaking consciously in the voice of the author. He also wrote the first topical law code, the first Hebrew grammar (inspired by the great new Arabic grammarians), the first complete siddur, the first running commentary on the Torah designed to provide the plain sense of the text, the first Arabic translation of the Tanakh, the first rhyming dictionary for Hebrew poets, the first Hebrew sacred poetry with a personal touch and the first literary polemics -- attacking the Karaites, Jewish heretics and the corrupt Resh Galuta. With the loss of Aramaic as the Jewish language, he created a tradition of Jewish creativity in Arabic (though it was written with Hebrew letters as Yiddish is today). His model of symbiosis between Jewish and general literary culture prefigured the great Jewish cultural creativity in German and later English in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. However he also promoted a broad revival of Hebrew as a spoken, as well as a literary language. 4 “Our heart and the living spirit within us are in pain over this, for the holy speech is absent from our mouths and the vision of all our prophecies and the speeches of God’s mouth are like sealed books to us…It is right for us to study Hebrew, to contemplate it and to examine it closely, we and our children, even our wives and slaves, so that the ordinary people of God will speak Hebrew when they go out and when they come in and in whatever they do, in their bedchambers and with their infants…” (Sefer HaEgron, Saadiah Gaon). He promoted a Judaism that could appeal to the well-educated Jews who appreciated the philosophic and aesthetic standards of the surrounding liberal Moslem cultural and religious renaissance around them. He was not afraid of a pluralistic dialogue with his non-Jewish colleagues – Moslems, Christians and philosophers – all of them professing monotheism. For Saadiah, revelation and reason were not in contradiction, science and religion were allies and self-ghettoization was unnecessary to maintain Jewish observance and a high level of Talmud study. Saadiah’s student, Dunash brought that same spirit to the other end of the Moslem empire and discovered in Moslem Spain that the Arab duchies included very highly cultured aristocratic Jews in their courts as economic and political advisors. These Jews were traditional in observance and proudly Jewish culturally and yet liberal minded in patronizing Jewish cultural arts like the academic study of Hebrew language and Bible and the creativity of court poets and literati, just as the Arab dukes did. For example, Shmuel HaNagid (993-1055) was both a Hebrew poet and a decorated general. Hisdai ibn Shaprut (915-970), the most prominent Jew of Cordoba, sponsored Menahem ben Saruq’s writing of the first-ever Hebrew-Hebrew dictionary because it would help Hebrew poets. The revival of the use of the Hebrew language for writing secular poetry about love, wine and friendship as well as new sacred works for synagogue use, became a model for the modern Zionist revival of Hebrew centuries later, led by the author of the first great modern th Hebrew –Hebrew dictionary, Eliezer ben Yehuda at the turn of the 20 century. Dunash made a big “splash” on the social scene by writing a devastating critique of Menahem ben Saruq’s magnum opus and inventing a new form of Hebrew poetry based exactly on the Arab canons of poetry. An armada of polemical poems were dispatched by each side against the other. The Jewish aristocrats who patronized these scholars and poets were themselves deeply caught up in what no one considered a mere academic issue. In the surrounding Arab world linguistic beauty was the key both to high culture and to religious truth since the Koran’s verses are thought of as descending from Heaven. Jews felt the need to demonstrate the equal aesthetic and therefore divine quality of Hebrew poetry. Dunash’s Dror Yikra and his other poetry set a new norm that captivated Spanish Jewry for 500 years and produced the greatest Hebrew poetry since the Bible and until modern Israel. Dunash wrote not only religious poetry but also court poems of wine, women and song. Yet even here he feels conflicted about the transitory value of these worldly delights when we remember Israel’s historic fate: There came a voice: “Awake! Drink wine at morning’s break. 5 ‘Mid rose and camphor make A feast of all your hours…. We’ll drink on garden beds. With roses round our heads. To banish woes and dreads We’ll frolic and carouse. Dainty food we’ll eat. We’ll drink our liquor neat, Like giants at their meat, With appetites aroused…. Scented with rich perfumes, Amid thick incense plumes, Let us await our dooms, Spending in joy our hours. I chided him, “Be still! How can you drink your fill When lost is Zion hill To the uncircumcised…. The Torah, God’s delight Is little in your sight, While wrecked is Zion’s height, By foxes vandalized. How can we be carefree Or raise our cups in glass, When by all men are we Rejected and despised?” (Raymond P. Scheindlin, Wine, Women and Death 1986 JPS p.41 Vaomar al tishan) A Lone Jewish Poetess Dunash’s wife who may have remained in Baghdad when he traveled to Spain, writes her own plaintive poem of love for her husband. This female poetic creation is one of the most unique finds from the medieval Jewish world. In this poem she holds her only son in her arms and recalls the exchange of gifts between her and her now distant husband. Will her beloved remember his friend (yedida) On the day of their separation in her arms he left his son, his only one (yekhida). From his right hand he placed his seal (ring) on her left (smola), 6 And on his arm she placed her bracelet (tz’mida). On that day she took as a memento his cloak (r’dido), And he as well took as a memento her cloak (r’dida) – Would he ever remain in Spain, Even if he were to receive half of the kingdom of its prince (n’gida)? Dunash replied with renewed profession of everlasting love and recognition of the uniquely cultured wife he had found: How could I betray a woman of culture like you? And God commanded us to cherish the woman of our youth (Malachi 2:14). If I had plotted to abandon my sweetheart, Then cut me into a thousand pieces. 1 Rabbi Yehuda Halevi (1075 in Spain to 1141 in Eretz Yisrael) – Leaving the Land of the Golden Age for the Dream of Jerusalem2 Why at age 66 would the greatest and most celebrated poet of the Jewish world abandon his comfortable and esteemed position to set forth on a long and dangerous journey to Crusader –dominated Jerusalem in the midst of the Moslem-Christian hostilities? Yehuda Halevi was no messianic mystic and no ascetic pilgrim looking for a grave in the Holy Land. He loved the creature comforts of the courtly existence in Spain, which he described in lush detail in his court poetry about wine, women and song. He lived a full life in a web of friendships with literati who all resided in Spain. So why did he set sail on a ship to Eretz Yisrael in 1141 C.E. on the first day of Shavuot, knowing as he did, that the meager Jewish community of Israel could provide him with no companionship and little realistic hope of spiritual growth in the violent age of the Crusades? Yehuda Halevi’s rapid rise to the top of the Jewish cultural world begins as a child born in Tudela near Sargossa. His home was located on the unstable border running between the warring parts of northern Christian and southern Moslem Spain. In 1085 Toledo was captured by the Christians and in 1090 the North African fanatic Berber tribes conquered southern Spain. The atmosphere of religious war threatened the tolerant, highly educated Arab ruling class who had encouraged Arab-Jewish collaboration, literary creativity and cultural cross-fertilization. Jewish refugees moved desperately in search of security and opportunity to maintain what they could from the Golden Age, which was facing an external catastrophe. Yehuda Halevi in fact grew up on the Christian side of the border in Castile, where nonetheless he learned the art of Hebrew poetry and the Arabic language of southern Spain, the heartland of Jewish cultural creativity. He utterly surprised and charmed Arabic-speaking Jews in Andalusia when he, as an unknown young man, triumphed easily in a competition of Hebrew poets who were all trying to imitate the aging giant of Hebrew 1 2 7 Ezra Fleischer, “Dunash’s Wife” in S.D.Goitein, Mediteranean Society, no.5 pp.468-470. See Yisrael Levine, Masao shel Yehuda Halevy. poetry – Moshe ibn Ezra from Granada. Moshe ibn Ezra then adopted Yehuda as a protégé and welcomed him as a houseguest. Here Yehuda met Moshe’s younger relative, Avraham ibn Ezra, who would become his traveling partner and close friend. (According to some traditions, ultimately Yehuda married off his only daughter to Avraham ibn Ezra ‘s son). Though he came from poor family with no pedigree, Yehuda’s physical beauty, charm, poetic genius, loyalty to friends and affability made him the most popular of poets and almost 800 of his poems survived due to the large number of copies made by his admirers especially those in Cairo, home of the largest Geniza ever found. In 1096 the Pope promoted a bloody Crusade to recapture Jerusalem from the Moslems. That Crusade met with amazing success in 1099. In the process, which initially raised Jewish hopes, thousands of Jews were massacred and /or forcibly converted in France and Germany and hundreds more killed, along with the Moslem inhabitants of Jerusalem. In Spain where the Christian Reconquista was picking up speed in reconquering the Moslem south, the Crusades raised apocalyptic fears and hopes not conducive to the previous Golden Age of high culture and tolerance. In reaction to the Crusades, Yehuda wrote a sensitive elegy for those Ashkenazi martyrs massacred by the Crusaders. Yehuda Halevi, by now a rabbi and physician as well as a poet, moved to Christian Toledo then administered by an enlightened Christian ruler and his activist and educated Jewish cabinet minister. Yehuda Halevi had prepared for the cabinet minister an official welcoming poem for his return from a diplomatic trip. However in 1108 word was received that the minister had been murdered by Christians. Yehuda understood that this was indicative of the impossible situation of the Jews caught between warring religious fanatics. From 1109 Yehuda Halevi wandered through southern Spain. He became the voice of the people writing elegies for the victims of Christian pogroms in Castile – northern Spain. He also spoke against the illusions of rapid return to long-term security in Spain – whether Moslem or Christian. As a politically responsible leader, he used his fame and his vast personal connections to raise money for, among other causes, a young Jew captured and held for ransom. In his philosophic masterpiece, The Kuzari (after 1125???), Halevi expressed his belief in the exclusive Jewish national and religious rebuilding of Eretz Yisrael and denied the competing claims of the Christians and Moslems who were then battling over military control of the Holy Land. In fact he insisted Eretz Yisrael could really only belong to the people of Israel who by their very nature belong to the land that nurtured them as the spiritual birthplace of the people. The poems about the national suffering and humiliation in exile along with the yearning of the beautiful Songs of Zion represented a uniquely “Zionist” sensibility at a time when a political or military movement for return to Israel was merely a pipe dream. In 1125 at the age of 50 Yehuda Halevi seems to have decided to make aliyah when he writes: “My manifest hope is to wander eastward as fast as possible, with God’s help,” yet he worries, “How can I repay my pledge and my vow [to make aliyah], when Zion is entrapped by Edom (the Crusaders) and I am imprisoned in Arab hands?…My heart is in the East, but I am in the farthest point of the West.” The practical difficulties and the constant opposition – in love and in ridicule – by the still proud Andalusian Jewish community prevented Yehuda Halevi from actualizing his dream for a long time. But he felt guilty for the hypocritical gap between Jews’ constant prayers for the return to Zion and their willingness to stay in Spain without any serious thought of actualizing their words of prayer. 8 Finally in 1140 at the age of 66 (= 4900 of the medieval Jewish calendar, 7x7x100 years since the Creation) Yehuda Halevi set sail with his family for Cairo where he was given a royal welcome by its wealthy, highly cultivated community. The Jews of Cairo tried to discourage Halevi from continuing on a dangerous sea journey to Eretz Yisrael. In those days bandits were rife and passengers often became hostages for ransom or slaves to be sold, if the unpredictable storms did not sink the ship. For over 800 years it was not clear whether Yehuda Halevi ever fulfilled his vow to settle in Israel. Only in the late twentieth century did scholars, sifting through fragments from the Cairo Geniza, discover the truth. Letters found in the Geniza proved that the dream was fulfilled in Halevi’s lifetime; he set sail on the first day of Shavuot in May, 1141and arrived in the Crusader-ruled land of Israel. Halevi passed away just a few months later in the month of Jewish mourning, Menahem Av. As much as his journey seems like Don Quixote tilting at windmills, Halevi’s act symbolized a direction, which, he believed, was the most reasonable and most honorable national option. Sadly his dire predictions about Moslem Spain came true only seven years later with the invasion in 1148 by the most fanatic fundamentalist Moslem warrior tribe – the Almohades (= believers in the pure unity of Allah) who forcibly converted Jews who became Moslem “Marranos” and subsequently took flight to north Africa or Christian provinces to the north. Maimonides, born in Cordoba in 1138, was probably one of those forcibly converted who with his family escaped to North Africa and ultimately, like Yehuda Halevi before him, to Cairo. However the meaning of Halevi’s aliyah is deeper than a national search for political security and honor. Yehuda Halevi was choosing the way of “freedom” that would liberate him from the constant need to find favor among his patrons and readers. The Rabbi in Halevi’s book of philosophy The Kuzari explains the motivation for the decision to emigrate to Eretz Yisrael: I am seeking freedom from the enslavement to the many…the incessant desire to find favor in their eyes. In its place I seek to be a slave to the [Divine] One for enslavement to the One is freedom and submission to God is the true honor. As he formulated this thought in one of his poems: The slaves of time are slaves to slaves / while only the slave to the Master (Adonai) is liberated. The way of freedom is ultimately the way of love. In finding one’s Divine Beloved – in one’s heart, one discovers a cure to all one’s ills. All fears disappear in one’s intimacy with the Lord. That desire for personal redemption to be found within one’s heart but also in the Holy of Holies in the Holy City was also part of the meaning of the fearless of an old man in setting sail for the land of Israel in the midst of acute political and military turmoil. The Geniza in Cairo The greatest Jewish archeological finds of the last century were the Dead Sea Scrolls preserving lost Second Temple Jewish literature hidden in the caves near Qumran from 68 CE until 1947 and the Geniza (meaning to “file away”) fragments of Cairo in 1896. The poem of Dunash ben Labrat’s wife, the last letters of Yehuda Halevi before setting off on his final voyage to Eretz Yisrael before his death and some of Maimonides’ writings in his own 9 hand were all thrown in with the sacred trash in a back room of the synagogue between approximately 800-1200. Thousands of documents which might have a holy reference to God were all treated with respect and “buried” there honorably. The room was sealed up when filled with thousands of old Hebrew manuscripts whether bills of sale, prayers or philosophical works. Not until 1896 did some of the documents find their way to a street vendor who sold them to two Christians from England who then shared them with the scholar Solomon Schechter then teaching at Cambridge. Schechter recognized the original Hebrew of Ben Sira’s second century BCE Book of Wisdom which had been lost for over a thousand years. Rushing off to Cairo to the Ben Ezra Synagogue, Schechter packed 100,000 pages into his suitcases to bring back to England. Thousands more pages were later collected and deposited in libraries from Russia to New York and are still being pieced together and catalogued. That discovery has given us a window into a thousand years of Jewish culture, much of which had been lost. For Jews who take their memories and even more so their cultural creations as their holiest heritage this was a gift of recovered past of inestimable value that has helped in the compilation of this book as well. Rabbi Avraham ibn Ezra – The Wandering Poet, Philosopher, Translator, Biblical Commentator, Grammarian, Mathematician and Astrologer Par Excellence (10893 in Tudela, Spain – 1164 in London, England) O for a clear way to keep your commandments! For only in Your love do I find rest. I am your servant; guide me in Your ways I have no care but to deserve your grace; I only ask that I may see your face. (Avraham Ibn Ezra translated from the poem Achalai yikonu by Raymond P. Scheindlin, The Gazelle 1991 JPS,) Avraham ibn Ezra, author of Ki Eshmara Shabbat, was the great wanderer of Moslem Spain who went into exile as result of the political catastrophes that ended the Golden Age of Spain. Though he suffered personally from his many exiles, he managed to bridge numerous cultures and to bring the fruits of Moslem Jewish Spain to many Jewish communities in Christian Europe – Italy, France and England. In southern Spain he learned poetry with his older relative, the great Moshe ibn Ezra and there became best friends with his slightly older contemporary the great poet Yehuda Halevi. According to some scholars Yehuda Halevi’s only daughter married his son. Avraham also had a promising son who converted to Islam causing Avraham great anguish. After the invasions from the Christian Spain to the north, and the counter invasion by fundamentalist North African Moslems from the south, many Jews began to wander in search of a new home for their once great culture. In 1140 Ibn Ezra began his exile, moving first to North Africa, then to various city states in Italy and from there to Provence and Ashkenaz. In France he met his colleague Rabbenu Tam and perhaps his brother Rashbam, both of whom were Rashi’s grandchildren and great Talmudic and Biblical commentators. Ibn Ezra finally ended up in London. In each location he earned his keep by writing and 3 Scholars debate the dates setting them around 1088/9 or 1092 to 1164 or 1167 10 rewriting commentaries on many of the books of the Bible, even though he did not have his library with him or the previous commentaries he had already composed. He also translated many Arabic works into Hebrew. Serving as one of the Jewish conduits of ancient Greek knowledge through Arabic into Hebrew and ultimately into Latin, Ibn Ezra brought a much higher understanding of Hebrew grammar to Ashkenazim who had little exposure to linguistics. He also invented a Hebrew numerical system with a zero notation learned from the Arabs. His commentaries – particularly on Shabbat identified with the seventh planet Saturn – conveyed what was then considered the science of astrology in which he was very well versed. He also used Shlomo ibn Gabirol’s neo-Platonic philosophy in his commentaries explaining that God created the world not from nothing but by a process of emanation. The Jewish Astrologer: Saturn and Saturday While, according to the great rationalist Jewish philosopher Maimonides, the Torah is designed to liberate Jews from astrological beliefs which should be viewed as idolatry – avodat kochavim umazalot / worship of stars and constellations, some medieval rabbis accepted astrology as true science and harmonized it with Jewish beliefs including Shabbat. The ancient Roman world sometimes used a seven-day week named after the seven planets (Uranus and Pluto were as yet undiscovered), each of which was identified with a god that ruled that day and gave it a particular character, such as Mars the god of war for Tuesday (Mardi). In Europe most of the days of the week are still named after gods, often identified with the heavenly bodies – Sun-day, Moon-day and in French Mercredi for Mercury. Even today Jews refer superstitiously to the constellations of the zodiac that are purported to control our individual fates – hence the wish Mazal tov / Have a good constellation to determine your fate! In medieval Jewish astrology, Shabbat is surprisingly associated with Saturn, the most malicious of planets. The Rabbis recommended, “Don’t go out alone at night especially on the fourth day of the week (associated with Mars) and Shabbat evening” (associated with Saturn) (T.B. Pesachim 112b). Avraham ibn Ezra explains the Shabbat commandment in terms of a wise strategy to countermand the negative influence of Saturn and Mars (which for Ibn Ezra was the ruler of Friday rather than Tuesday): The fourth commandment [to observe Shabbat], corresponds to the planet Saturn [called Shabbtai in Hebrew]. For the astrologers [hachamei ha-nissayon] say that each of the heavenly planets [servants in God’s cosmos] has a specific day on which to manifest its power…It is said that Saturn and Mars [Ma’adim, the red planet] are harmful planets, and anyone who begins a new task or embarks on a journey on one of these days come to harm …Nor will you find among all the days of the week a consecutive night and day governed by these malicious forces except for this day [Shabbat since Mars governs Friday evening and Saturn governs Saturday during the day]. Therefore it is appropriate not to be involved in any worldly activities but only in the service of God alone. (from Ibn Ezra’s long commentary on Exodus 20:14) 11 The Kabbalist Poets: HaARI - Yitzchak ben Solomon Luria (1534-1572) - Yom Zeh L’Yisrael Yom Zeh L’Yisrael has been traditionally attributed to Yitzchak HaARI whose name forms its acrostic, even though scholars have discovered that its opening five stanzas were written earlier. It was natural to make this attribution since HaARI wrote three famous Aramaic Zemirot – one for each meal of Shabbat. Those Zemirot were thoroughly immersed in Kabbalist imagery and language. Though they have not been included in our collection since they are less popular today, this is an excellent occasion to review the biography of Isaac ben Solomon Luria (1534-1572) in brief because he was so central in the movement in Safed that formulated and popularized so many of the Shabbat evening ceremonies and their mystical interpretations. Isaac Luria was later referred to reverentially as the ARI” – “the divine Rabbi Yitzchak” / A= ha-Elohi ; האלוהיR=Rabbi ;רביI = Isaac -יצחק, although his Sephardi contemporaries in Safed called him simply “Rabbi Isaac Ashkenazi.” His father emigrated from Germany or Poland to Jerusalem and married into a Sephardi family. Since his father died when he was a child, HaARI was raised in the home of his mother’s wealthy brother in Egypt. Luria quickly became known as a brilliant scholar. Documents in the Cairo genizah indicate that while in Egypt he was also a businessman who traded in pepper and grain. While still quite young, he began his mystical studies and spent seven years secluded on a small island on the Nile near Cairo owned by his uncle (whose daughter he married). There he studied the Zohar, the works of earlier kabbalists, and especially the writings of Moshe Cordovero. During this period, he wrote his only book, which was a commentary on part of the Zohar. Yitzchak Luria settled in Safed in the beginning of 1570, where he studied with Moshe Cordovero. After Cordovero’s death at the end of 1570, Chaim Vital become Luria’s chief disciple. HaARI rarely taught in public, but often took long walks with his disciples and pointed out previously unknown graves of important sages. He developed an original system of theoretical Kabbalah, based on unification of the sephirot, concentration on divine names, and kavvanah – meditation on the act of prayer. Luria preferred the Sephardi liturgy. For this reason, Ashkenazi kabbalists, and later Hassidim inspired by HaARI chose to use the Sephardi liturgy. He died in an epidemic on July 15, 1572, and his grave is still a place of pilgrimage. Before Luria’s theoretical teachings became popular, some of his poetry became famous. Best known are his three Zemirot for each of the Shabbat meals. 4 HaAri s Aramaic Zemirot helped transform the three Shabbat meals into a mystically dramatic ritual. In the light of the Zohar which had now become increasingly accessible to more and more Jews, Shabbat Zemirot were considered wedding songs used to honor the Shekhina’s union with the other Divine Sefirot, just as Kiddush was a reenactment of the Kiddushin wedding vows. The well-being of the Divine and the earthly worlds depended 4 This biographical synopsis is based on a summary provided the Jerusalem tour guide Asher Arbit 12 directly on human efforts to arouse the Shekhinah’s mystical love and thereby bring down her blessings. The ever-widening circles of Jews interested in mysticism and its new rituals needed songs to sing for these new informal rituals which lacked an inherited fixed liturgy or a halachic structure and often did not take place in the synagogue at all. This era witnessed an overwhelming spiritual outpouring at all levels of Jewish society. 13 Rabbi Yisrael Najara – the Controversial Spiritual Singing Star| of the th 16 Century (1550-1625, Safed, Damascus and Gaza) 5 A somewhat exaggerated “promo” for Rabbi Yisrael Najara, the author of the Aramaic Shabbat favorite Yah Ribon Olam, might present him as the most controversial and yet the most successful Jewish songwriter since the author of Tehillim / Psalms --King David. David’s soul was, according to Yitzchak Luria, reincarnated in Yisarel Najara’s soul for David was known as Ne’im Zemirot Yisrael – the “sweet singer of Israel.” Najara’s commercial success transcended everyone – publishing three editions of his books in his lifetime with almost 300 sacred songs written especially to be sung to popular Turkish melodies. (Recall that printing presses had just begun to serve popular audiences in this area of Hebrew songs). An early tradition attributed posthumously to HaAri, Rabbi Yitzchak Luria (died 1572) claims that the angels who come to his table on Shabbat love Yisrael Najara’s tunes and sing them like wedding melodies before God and the Shekhina. Yet Haim Vital, HaAri’s primary student, writes scathingly of Najara for singing loudly and carousing with non-Jewish minstrels in the park. He was accused of dressing immodestly, appearing without the accepted big hat and with his arms partially exposed. He was reported to have joined drinking parties with non-Jews even during the three-week mourning period before Tisha B’Av when the destruction of the Temple is commemorated. When Haim Vital exorcised a dybbuk /a spirit that had entered the body of a woman from a good family, the dybbuk proclaimed that although Yisrael Najara’s songs were well-written, no one should drink with him or speak with him. Najara’s popularity derives from the use of popular Turkish and Arab love songs – their lyrics as well as their melodies – for Zemirot designed to commune with God. Previously, the dominant religious poetry of Sephardic Jewry followed an aristocratic Spanish tradition into which Yisrael was born. For example, Rabbi Yehudah Halevi who wrote Yom Shabbaton and Rabbi Avraham Ibn Ezra who wrote Ki Eshmara Shabbat had adopted the ornate upper class Arab poetic style and adapted it to Hebrew for use in the cultural circles of wealthy Spanish Jewish cabinet ministers. The youthful Yisrael Najara learned this style, preserved by the immigrants from Spain (Yisrael’s grandfather was an exile from Spain whose name Najara derives from the name of a town in Spain). But soon he and all his generation of Jews were drawn to the more popular songs from their new non-Jewish cultural environment – the Ottoman Empire. Its lively refrains were written and performed by Turkish and Arab musicians and songwriters who wrote melodramatically of love and of suffering. Young Jews were drawn to these impromptu jam sessions both on holidays in public parks – especially in Damascus, the most beautiful of cities in this era - and late into the night at the newly faddish coffeehouses even in Safed. The more established rabbis complained bitterly about these social gatherings. Yisrael himself emerged from this rabbinic elite; he was a rabbi and the son of a great Talmudist as well as a colleague of Yosef Karo, author of the Shulkhan Aruch. He was also a student of the mystic master HaAri. Yet along with his learning he 5 See Meir Benayahu in Asufot No. #4 pp.203ff and Yosef Yahalom in Pe’amim #13 pp.96ff and Tarbiz #60 pp.625ff 14 developed as a fine musician and virtuoso performer. He was also an artistic calligrapher and became the scribe of the Jewish community for official letters, as well as an inspiring synagogue orator/darshan. Perhaps he was also a painter of ornamental objects and one who inscribed verses over the doorway, as was customary at that time. The musical revolution described above had its more conservative and its more radical promoters. Yisrael Najar was the radical borrowing readily from popular non- Jewish romantic sources, while his opposition was Menachem de Lonzano of Jerusalem who published his own song book based on the use of more sorrowful Turkish tunes: “God knows… that I did not compose songs using Moslem melodies in order to encourage carousing with drums, halil (recorder) and wine. I chose only those Arab melodies that I found expressed a broken heart and I thought they would be helpful to conquer my uncircumcised heart …Therefore they should not be sung on Shabbat and holidays…In this I differ from Yisrael Najara who makes no distinction between Shabbat and Tisha B’Av.” 6 The more radical innovator was Yisrael Najara who explains in the preface to his bestseller Zemirot Yisrael (1587): “I seek to quench the thirst of those seeking the word of God [through song] and to win over those Jews who now sing Turkish melodies with pornographic words…Surely anyone who can enjoy what is permissible [singing sacred Hebrew songs to God] will leave aside the Turkish lyrics since my melodies are exactly the same but with holy Hebrew lyrics.” Each of Najara’s songs was written to match the musical pattern of already well-known melodies and often Turkish song’s title was written alongside the Hebrew lyrics. Therefore anyone could learn to sing Najara’s songs instantaneously. However the truly radical move promoted by Yisrael Najara was to apply the content of very explicit love songs to the love of the people of Israel for God. For example, a famous Spanish love song dedicated to Seòora became Shem Norah / God’s Awesome Name. Haim Nachman Bialik, the national poet of the Zionist movement, who loved the classical poetry of the Golden Age of Spain, complained bitterly of Najara’s borrowing from “lowly sources of poetic inspiration:” How could Rabbi Yisrael Najara take the melody of an Italian “Don Juan” holding a bouquet of flowers, carrooning to his “Seòorita” in Italian before her window on a spring evening.(?) Then they sing the same song with ashes on his head while sitting before the Holy Ark at midnight in a Kabbalistic Tikkun ceremony using these lyrics now in the holy tongue redirected toward the Holy One Blessed Be He!? 7 Yet that was exactly what was called for in the popular Kabbalist revival that began in Safed and spread throughout the Mediterranean and then beyond “carrying and carried by” the songs of Najara. His music and lyrics could – unlike the classical poetry of Spain or the scholarly poetry of Ashkenaz – convey mystical meanings regarding the communion of the Divine male and female aspects and the passionate romance of the soul for God. The Ari is said to have rejected the abstract non-mystical intellectual poetry of Spain such as Yigdal, 6 [See the original quotations brought in the articles mentioned above in previous footnote]. 7 15 H.N.Bialik, Shirateinu Hatz’ira, HaShiloach #17 p.72 which summarizes Maimonides’ 13 principles of faith. However his followers could sing Najara’s hits, even though they were not suffused with mystical doctrines as were the Ari’s Shabbat Zemirot. Najara’s songs were intended as allusions to the Divine lovemaking recalled King Solomon’s Shir HaShirim / Song of Songs and they were used in the new kabbalist customs created in Safed including: Kabbalat Shabbat, the midnight Tikkun on Rosh Hodesh, Hoshana Rabbah, Shavuot, and pre-dawn prayers like Selichot. Yisrael Najara himself was famed for his teshuvah / repentance sermons on Rosh Hodesh evenings and his music filled a spiritual and social need. How we may ask did the established rabbis of the period regard this mixing of the Jewish and the non-Jewish, of the sacred and romantic? Despite the reservations of the some 8, the majority regarded this as a legitimate and mainstream mystical effort, even though this particular music and style of lyrics was so new to Spanish Jewry. The great mystical scholar of Safed – Rabbi Moshe Cordovero (died 1570) who was also HaAri’s master – wrote: All descriptions of males and females in the Song of Songs refer to spiritual/heavenly intercourse – not God forbid, physical/earthly intercourse. All who sing these songs thinking of their material meanings will destroy many worlds, but those who sing them with beautiful spiritual intent are builders of many worlds.” “Anyone who composes a song with a parable about a woman sitting in mourning for the husband of her youth, may portray her crying for him and imagine her physical needs for food, clothing and sexual gratification and her heart filled by love and desire, for this woman is clearly a reference to the Shekhina / the Divine Presence who dwells with him. This is on condition that no physicality but only spirituality is intended. 9 In this use of earthly imagery for heavenly communion we find that the Muslim Sufis, the Whirling Dervishes of Turkey, followed the same pattern. In fact, one of Yisrael Najara’s most famous poems used in the Sephardi tradition every Shavuot is the Ketubah of God and Israel celebrating their marriage at Mount Sinai on Shavuot. Najara’s songs continue to be popular and each generation gives them a new musical interpretation. One of the most remarkable uses of these popular songs goes back to 1621 when at age 71 Yisrael Najara was appointed the rabbi of Gaza, a small, undistinguished Jewish community. After him, his son and grandsons served as the city rabbinic authorities. When Rabbi Nathan of Gaza, Shabbtai Zvi’s spiritual mentor and promoter, preached that Shabbtai was the mystical messiah he won over Yisrael’s grandson and soon Najara’s songs – with new interpretation – became very popular for Sabbateans. 8 On Soul Music and Scandal - Reb Shlomo Carlebach: Interestingly there are some similarities in the controversy about music, popular th spirituality and rumors of sexual promiscuity that surrounded both Najara in the 16 century and enveloped Shlomo Carlebach in the twentieth century. . Reb Shlomo Carlebach, Hassidic singing star and spiritual leader of many Baalei teshuiva, found music a way to reach out to broader masses and to bring assimilated Jews closer to a more spiritual Judaism. His songs have now became widespread best-sellers even among establishment Orthodox congregations even though established figures once condemned his behavior which was often surrounded by rumors. 9 Moshe Cordovero, commentary on Shiur Koma 33:4; 34:1. 16 Rabbi Elazar Azikri (1533-1600, Safed) – The Mystical Diarist of Yedid Nefesh and his Holy Contracts The mystical diaries of Elazar Azikri, author of the famous Shabbat song Yedid Nefesh, are a unique phenomenon in Jewish literary history. In his diary Azikri traces his four-decade struggle for moral perfection with his fellow human beings and for spiritual concentration on the Beloved of his Soul/Yedid Nefesh – God. Azikri began to document his inner life immediately after the tragic death of his two sons in 1564. The author describes how he strives for communion with God using most unusual techniques. Besides studying Torah and mysticism, he spent one third of each day standing in absolutely silent meditation. He also entered into a binding legal contract - a shtar with the Master of the Universe, dated 1575, attested by two witnesses and containing binding clauses. The witnesses who “signed” are Heaven and Earth as in Moshe’s poem Haazinu (Deuteronomy 32). The stipulations were read aloud four times a day – at sunrise and sunset and at noon and midnight. They include: loving people and not prejudging them contemplating God at all times and refraining from worldly activities praying with enthusiasm giving tzedakah every night before going to sleep crying regularly except on Shabbat and holidays visiting the graves of righteous spiritual masters Rabbi Elazar Azikri combined interpersonal and spiritual mitzvot because he believed that God’s name is inscribed in the face of each human creature. He identified the four letters of God’s unique name – Yud Heh Vav Heh – with which he began each of the verses of Yedid Nefesh – in the facial structures of his fellow Jews. The ear is like Yud; one cheek is like Heh; the nose is like Vav; and the other cheek is again like Heh. The idea is that whenever we encounter a fellow Jew, we are looking at the face of God and must do so with reverence and even lower our eyes as we would in confronting a majestic Ruler. In 1575 he created a new legal document called a Brit Hadasha / a New Covenant perhaps in the spirit of Jeremiah’s new covenant (which is translated by the Christians by the term New Testament): “A time is coming – declares God – when I will make a new brit/covenant with the House of Israel …and I will put my Torah inside of them and write it on their hearts” (Jeremiah 31:3032). That contract bound together a Holy Havurah of three rabbis in Safed and listed ten conditions including: maintaining the unity of the three mystics (who would also share all their property equally) honoring both our heavenly and earthly parents suffering insults in silence while honoring all creatures and despising and ridiculing none studying with spiritual intensity the MiSHNA (the Rabbinic code of Oral Law) for that gives wings to the NiSHaMA / Soul which shares the identical letters accepting the yoke of God’s kingdom in our hearts constantly - without distraction This Holy Havurah expressed their personal love for God by speaking to God regularly in private and “by singing before God to arouse their love – more wonderful than the love for women” (as King David said of his love for the fallen Jonathan in II Samuel 1:26). In Rabbi Elazar Azikri’s book Sefer Haredim (1601) he published the songs of beloved friendship with God that he shared with his friends in the Havurah. The most famous was Yedid Nefesh which we sing on Shabbat when we too 17 withdraw somewhat from worldly activity and create space – like a honeymoon for lovers - for spiritual love with the Divine in ourselves, our friends and the world. Elazar Azikri, like his teacher Moshe Cordovero and his colleague Haim Vital, recommended a weekly spiritual week-in-review for the chaverim / members of the havurah who would meet in the synagogue before Shabbat and would tell and discuss with one another how they had behaved – whether properly or not - during the past week and then proceed to greet the Shabbat Queen. .” 10 10 See Meir Benayahu, “Shtarei Hitkashrut shel Mikubalim bSafed and Mizrayim” in Asufot 9(1995), pp.131ff. 18