CURRULUMBLD05 - University of Windsor

advertisement

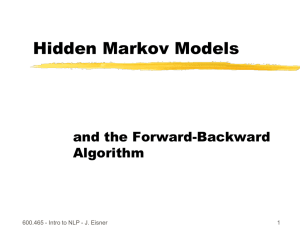

Dr. Wilfred A. Gallant Associate Professor School of Social Work University of Windsor Windsor, ON N9C 3K1 February 12, 2016 Dear I wish to sumit the following article entitled: “A New Perspective in Curriculum Orientation: A Synthesis in Social Work Education” for review in your journal. As requested, please find four printed copies of the article, a 3.5 inch disk saved in Wordperfect9 as: wilmikemelsherw2002.wpd. A separate electronic copy has been forwarded to your e-mail address ___________________ on Wordperfect9 and saved as: wilmikemel.wpd. All references and formatting is in APA style Should you have any questions, please feel free to contact me at (519) 253-3000, ext. 3071 or Dr. Holosko at 3075 if necessary. Sincerely yours, Dr. Wilfred A. Gallant Associate Professor cc. Dr. Michael Holosko & Ms. Melanie Gallant 1 A New Perspective in Curriculum Building 2 Cognitive, Affective and Experiential Elements in Social Work Curriculum Building: A New Perspective in the Synthesis of Social Work Education or A New Perspective in Curriculum Orientation: A Synthesis in Social Work Education Wilfred Gallant, Ed. D., M.S.W., R.S.W., I.C.A.D.C.ab, Michael Holoskobc, Ph.D., M.S.W., Melanie Gallantd, M.A., B.A., B.Sc. a Associate Professor of Social Work, Telephone (519) 253-4232, ext. 3071; FAX (519) 973- 7036; e-mail BL1@ uwindsor.ca. b Social Work, University of Windsor, Lambton Hall, 401 Sunset Avenue, Windsor, Ontario N9B 3P4, Canada. c Professor of Social Work, Telephone (519) 253-4232 , ext 3075, FAX (519) 973-7036; e-mail holosko@ uwindsor.ca. d Doctoral Student in Applied Social Psychology, University of Windsor, Windsor, ON, (519) 971-9489, e-mail, mgallan2@uwindsor.ca . This paper is intended for possible publication in The Electronic Journal of Education Running Head: A New Perspective in Curriculum Building A New Perspective in Curriculum Building Date of Submission: 3 February 12, 2016 A New Perspective in Curriculum Building 4 Abstract This article identifies a method of integrating five major curriculum orientations combined with an understanding model of teaching and learning which addresses both content and process. The purpose, therefore, is to explain these combined orientations for social work curriculum building. This approach broadens the professional base of social work by incorporating knowledge from the fields of education, educational psychology, counseling and generic social work practice. This article provides a parallel description between the processes of thinking, feeling and doing carried out in the field of social work and those elements related to the cognitive, affective and behavioral dimension in social work education. The article concludes with an eclectic and synergistic stance to curriculum building, offers student feedback and suggestion for teachers in higher education. A New Perspective in Curriculum 5 Cognitive, Affective and Experiential Elements in Social Work Curriculum Building: A New Perspective in the Synthesis of Social Work Education A New Perspective in Curriculum Orientation: A Synthesis in Social Work Education The quality of teaching and learning is at the heart of contemporary debates about the success and failure of our higher education system and there is a growing need for teachers to pay heed to curriculum design, integration and implementation (Passe, 1995). What should be included in the curriculum has been a major philosophical concern since the time of Plato (Kelly, 1989). Traditionalists, giving way to conceptual-empiricist, have all too often narrowed curriculum and instruction to generalities which ignore the specificity of each situation, and the inherent qualities which the learner and the teacher bring (Curran, 1976; Taylor, 1986). The most difficult task for educators might be to think creatively ‘outside the box’ and to relinquish the ‘school bus mentality’ that seems to be permanently fixed to all too familiar and comfortable traditions (Eisner, 1994). The conservative influence of universities on secondary education is further fostered in higher education as it restricts educational opportunities for students (Eisner, 1994). This paper redresses this imbalance by focusing on the classroom climate that evolves when both the unique person of the teacher and of the student engaged in the educational enterprise is taken into consideration. In this type of environment, the instructor is a vital facilitator of the ‘teaching’ process and students are an integral aspect of the ‘learning’ experience (Common, 1991). Educational theorists, whose major intent is to upgrade educational systems and to improve the performance of those within, have identified, among others, five major orientations to curriculum, often referred to as curriculum ideologies (Eisner, 1985). These include: 1) cognitive processes, 2) human technology, 3) self-actualization or personal relevance, 4) social reconstruction, and 5) academic rationalism (Eisner, 1985; Eisner, 1998). This paper incorporates these five orientations or ideologies to curriculum in light of the use of the "understanding model" (Curran, 1976) of teaching and learning, and demonstrates the implications and relevance of these dimensions for social work curriculum building. Additionally, A New Perspective in Curriculum 6 this paper demonstrates the use of an androgogical approach to adult education which applies the cognitive concepts of knowledge (thinking), the affective aspects of values (feeling) and behavioral dimensions of skills (doing) gleaned from the practice of social work. More importantly, this paper will describe selective elements of educational content and process and conclude with an eclectic and synergistic stance to teaching and learning. I. The Understanding Model Our effectiveness as teachers depends on our ability to empower students for professional and educational achievement and to improve the teaching/learning enterprise (Common, 1991; Eisner, 1985; Eisner, 1998). Such effectiveness is built upon a mutual understanding between teacher and student. Curran (1976) developed the "understanding model" in his research on the application of psychological counselling to the learning process. This humanistic approach recognizes the personal worth and dignity of both teacher and learner and focuses on students' task to learn specific social work content and to identify with the person of the teacher. In turn, the teacher identifies with the student’s unique method of integrating new knowledge and experience. Through this existential model, students gain an appreciation of the cognitive, affective, behavioral, and experiential components of the learning experience (Egan, 1998). This model provides for harmony among students' unique selves and their acculturation to the social work profession. The process by which students come to identify themselves as social workers emerges through the personal integration of theory and practice skills in the classroom. This is accomplished most effectively when the basic purpose, knowledge, attitude and skills in social work intervention are introduced and used dynamically and systematically in the classroom itself and when students are able to ‘navigate’ effectively through the process (Cox, 2001). Teachers also benefit because their dialogue with students in class becomes a rich experience that promotes their own integration of person, professor and model of a social work practitioner. The "understanding model," is akin to the "personal relevance and self-actualization" orientation to curriculum. As such, it presupposes a symbiotic relationship whereby teachers and students are deeply in need of each other and actually reaching out to each other for their own A New Perspective in Curriculum 7 mutual fulfillment – the professor as ‘committed’ teacher and, the student as ‘invested’ learner (Schwartz, 1961; Shulman, 1999). Potential social workers are best nurtured in a mutually supportive environment that frees teachers to give willingly and to share their knowledge while assisting their students to open themselves to receive wisdom and insights that will hopefully become the beginning impetus for their personal and professional growth. In respect to this educational dynamic, Towle (1954) was conscious of both the protective and integrative function of the ego. She saw the role of the teacher in social work education as an opportunity to nurture the ego for growth and sensitivity to the emotional and intellectual demands of learning. She had hoped that social work educators would collaborate with education professors and researchers for the mutual advancement of teaching and learning. The "understanding model" acknowledges the striking parallel between a student's resistance to new knowledge and the resistance professional social workers experience in their clients when confronted with change. If students are led to recognize and appreciate resistance in themselves in a learning setting, they will become far more adept at perceiving resistance and threat in their clients. It is believed that this ‘hands-on’ experience will help them learn how to intervene more effectively in their clients' lives. Social work education that fails to take the creative tension inherent in learning into account creates a self-defeating bind. In the humanistic model, resistance in a classroom is no longer viewed as a stumbling block, but is seen as a building block for authentic learning. Using the "understanding model," students are encouraged to respond in an enabling way to the presentation of the teacher very much as they would be called upon to provide such responses to their clients. These enabling responses move the teacher to share his/her personal knowledge and knowledge of social work with increased vitality and self-determination (Biestek, 1957; O’Neil-McMahon, 1996; Timberlake, Farber, & Sabatino, 2002). Such sharing is as essential to the teaching/learning process as it is to effective social work practice. In turn, the teacher empathically responds to the needs of the students in helping them make sense of their educational experience and in dealing with the blocks which make it difficult for them to learn. The rewarding qualities possible in an interpersonal relationship between a student and teacher are of paramount significance because these skills are parallel with those that will ensure A New Perspective in Curriculum 8 effectiveness in the fundamental relationship between a client and social worker. Thus, students can become more effective practitioners by applying the social work skills of attending, active listening and responding in the classroom (Cournoyer, 2000; Egan, 1998). Just as clients need space to tell their own story in their own way, so too teachers and students have a corresponding need to be mutually understood and respected in what they bring to the class experience. When teacher and students both feel convalidated, they both recognize their own creative resources (Shulman, 1999). I The Three Dimensions of Thinking, Feeling and Doing Paralled with the Knowledge, Values and Skills of Social Work. Towle (1954), who was exposed to the era of progressive education with its emphasis on the role of education in the growth process, focused on the ego investment of the student as a critical aspect of the educational experience. According to her, the role of the teacher consisted of an empathic relationship that strengthens students' potential and incentive, subsequently reinforcing their capacity for growth in order that learning may proceed rather than become constricted. She was particularly influenced by the work of John Dewey and William Kilpatrick who both emphasized an individualized whole-person, student-centered approach to education as opposed to a mere subject-centered model. According to Dewey, self-expression, growth, development and self-realization are the essential factors in the person-centered approach (Gitterman, 1972, Kelly, 1989). Knowledge must be internalized and transformed into skillful action (Gitterman, 1972). Our primary objective in terms of ‘knowing’ and ‘doing’ must be to acknowledge and to sketch the dialectical relevance of the relation between the general, the abstract, the specific and the concrete in such a manner that each of these elements contributes to the transformation of the other (Taylor, 1986). According to Towle, the social work educator should adapt her/his casework learning--meeting individual needs, wants, goals and capacities so as to alleviate unfavorable conditions--and apply this knowledge in the classroom as it pertains to the student’s integrative learning. This approach reduces barriers to productive learning and subsequently fosters personal and professional growth. Students' identification with their teacher, and hence with the development of their own professional competence, requires a shift from their former way of A New Perspective in Curriculum 9 ‘thinking’, ‘feeling’ and ‘doing’ to their development of a more professional stance. In social work supervision, for example, as well as in social work education, "knowing" is not equivalent to "doing". According to Rothman (1973), contemporary educational theory and practice sensitizes the teacher to the problems and potentials in the teaching/learning enterprise. According to her, knowledge and process are central ingredients in generating and sustaining learning. The teacher actively guides each student in discerning patterns of knowledge and integrating these into practice. A phenomenological inquiry focuses on human perception and the feelings they generate (Short, 1991). An individual comes to know through the symbolic transformation of experience which encompasses three phases of mental activity: a) ‘perceiving’--of new data in the environment, b) ‘ideating’--when students think and talk about what they have perceived, and c) ‘presenting’--testing the concept or notion with others. In terms of ‘perceiving’, the first contact is through the senses. This is where students receive new data. It is at this point that distortion of perception calls for a ‘caring confrontation’ by the teacher to correct misperceptions so that students can see the world more accurately (Brook-Smith, Goodman & Merdith, 1976; Egan, 1998). Though ‘ideating the intellectual and feeling dimension are stimulated by the student’s need to know. In this respect, the teacher provides a stimulating environment. ‘Presenting’ provides students the opportunity to symbolically represent the meaning of concepts to others on their own terms (Eisner, 1994; Brooks-Smith, et al.,1976). It is the task of the teacher to extend students' perceptions and the proclivities they possess to help them validate these perceptions. As teacher and students share experiences, ideas, constructs, and generalizations as tools for disclosing the whole of a problem and its fundamental elements, a model is projected of what ultimately must go into the learner's own private world of ‘knowing’, ‘thinking’ and ‘doing’ creating for the student a ‘logic of discovery’ (Curran, 1979; Eisner, 1994; Eisner, 1999; Rothman, 1973). For a teacher to make a difference, he or she has to focus on experiences, namely the experiences of the students, which is the basis for student-centered learning and the foundation for effective problem-solving and the effective delivery of service, in effect, doing what they ‘know’ and what they can ‘do’ in situations that matter (Common, 1991, Eisner, 1999). The ‘logic of discovery’ entails a process of evaluating the trials and corrections of the social 10 A New Perspective in Curriculum work content informed by the student and put into practice, evaluating the corrections made in the field and providing reason-based evidence for the student’s interpretation of the material (Blochowicz, 1998; Miller & Morgan, 2000), These three processes explored by Towle and Rothman parallel the ‘knowledge’, ‘values’ and ‘skills’ of social work practice and are shown in Figure I According to Rothman (1976) and Towle (1954) ‘knowledge’ or ‘thinking’ relates to knowing social work knowledge and attitudes. Any false interpretations which the students demonstrate calls for appropriate information on behalf of teacher and student. Values or feelings addresses the emotional development of the student, their individualized learning experience, their energy level, the attitude and feeling tone with which they engage in the process. The skill or doing of social work practice calls for students to test their new-found knowledge in classroom simulations, video taping and in their field practice. These three creative dimensions are based on assumptions which are still alive and well in the educational system today (Eisner, 1998). According to Gallant (2002), in social work education, ‘understanding’ is akin to knowledge, ‘integration’ is akin to values , and ‘operationalizing.’ is akin to skills. ‘Understanding’ the course content and the classroom process as well as the uniqueness which both the teacher and the student bring to it, is of primary importance. Misunderstanding calls for re-presenting content or classroom process or dealing with intellectual blocks that impede authentic learning. ‘Integration’ deals with personalizing the learning, and pulling things together where the teacher provides the optimal opportunity for a meaningful integration of content to occur. ‘Operationalizating’ entails putting into practice what is uniquely learned in the classroom, from the review of the literature and in the various learning exercises. In this model, students can ‘make’ their own meaning out of what is taught rather than be ‘spoon fed’. Subsequently, through their own self-determination (Biestek, 1957) and empowerment, they can search for knowledge and truth in their own unique way (Eisner, 1999). Creating a participative culture in the classroom is not without its concomitant tension. These tensions need to be addressed in one way or another by the teacher (Snow, 2001). In this regard, the concept of counseling/learning can be appropriately applied directly to the educational experience. The teaching/learning process is seen as a unique experience in personal growth, A New Perspective in Curriculum 11 development, integration and fulfillment for both the teacher and student. The latter's difficulties and blocks, particularly on the emotional, instinctive and somatic levels, are of major consequence (Curran, 1972, p. 4) Early in their relationship, the professor recognizes anxiety in the learner, becomes a sensitive, perceptive counselor, and thus helps her/him through anger or emotional blocking. The student gains security and confidence to trust the knower and to internalize the social work knowledge that is being conveyed to them. This counseling/learning model and the renewed educational experience incites constructive learning in the classroom as opposed to what is regarded as traditional "defensive learning" (Curran, 1972, pp. 4-5). Clemence (1965), using a student-centered philosophy, sheds light upon the continuity between education and casework (therapeutic intervention) when he states that both challenge the latent capacities of individuals and maximize their potential. By evaluative feedback, the social work educator can aid students to integrate their learning and help them progress toward professional maturity. In order to facilitate and accomplish this transfomational process, student learning must be a joint effort between teacher and student. This requires a balanced flow between theory and practice and between educational content and process at three critically significant levels: educational learning, personal growth and professional competence. The three factors of: a) understanding, b) integration and c) operationalization or the parallel of a) knowledge [thinking], b) values [feeling] and c) skills [doing] of social work practice are critical ingredients of selfinvested learning. These three factors are consistent with the concepts developed by BrooksSmith, Goodman and Meridith (1976) who have identified three dimensions of ‘ideating’, ‘perceiving’ and ‘presenting’ (1976). ‘Understanding’ imposes order upon our experiences as we uniquely perceive our identity and relatedness to others and to the subject matter. For example, if we take the simple understanding of words. The words ‘stubborn, ‘obstinate, and ‘pigheaded’ are defined in the dictionary as ‘not easily influenced’. If we examine them more closely within a cultural context there is a significant variant in our perception and interpretation of the words. For instance, ‘firm’ is considered a good thing, ‘obstinate’ is a less desirable thing, and ‘pigheaded’ comes across as a nasty thing. ‘Understanding’ and ‘perception’ require careful communication between the teacher and the learner in order to insure optimum learning and accurate absorption of content (Kelly, 1989). Figure 1 compares these three models of curriculum. 12 A New Perspective in Curriculum Insert Figure 1 Here III. Androgyny There are further insights to be gained for social work education by focusing on the distinct elements which pertain to androgyny – the teaching of adults in higher education (Tweedel, 2000). Malcolm Knowles (1972) proposed a classical androgogical approach which makes adult education more exciting, relevant, dynamic and real. He postulates four basic dynamics: 1) changes in self concept, 2) the role of experience, 3) readiness to learn and 4) orientation to learning. An androgogical design for learners entails: a) setting a climate, b) mutual planning, c) diagnosing needs, d) formulating program objectives, e) planning a sequential design of learning activities, f) conducting the learning experience, and g) evaluating the learning. The thrust of Knowles' work in creating educational environments calls for maturing professionals who can develop and expand the models of competency through mutually self-directing inquiry (Common, 1991; Kelly, 1989). For example, by having the students conduct a ‘do you best’ video tape with a fellow student, allows them to obtain a birds eye view of what they need to learn to enhance their social work skills. Also, a written contract gives them the opportunity to decide what needs to go into their learning to improve their effectiveness as a social work practitioner. Most importantly, writing critical reflective diaries or bibliographacies allows them to internalize their readings and to give them meaning in a manner that will enhance their skills as social workers. IV. Eisner's Pioneering Work There is a complementary manner in which art form can be used in the design and evaluation of educational programs. Eisner has developed useful, educationally significant curriculum programs and has legitimized artistic form for describing, interpreting and evaluating what transpires in the classroom. As a result, he has seen dramatic changes in students, especially his doctoral students. Eisner (1985, 1999) challenges the narrow confines of scientific inquiry when applied to education because he believes that educational environments can encompass both A New Perspective in Curriculum 13 scientific and artistic elements With the virtual demise of behaviorism, he opens new ground for contemporary education by drawing assumptions from art and art education which in the past have not been characteristic of educational inquiry. In order for teachers to deal with the organization of planned activity, they need not always start with aims or objectives and then deductively proceed to evaluation. According to Eisner,(1985, 1999) curriculum development has both a practical and an artistic component which require prudence, wisdom and practical insight as they relate to the realities of the classroom. The artistic elements of taste, design and fitness must blend together, make sense and be aesthetic. Eisner (1985) is aware that conceptual notions with strong educational appeal need to be enriched and modified in order to be functional. Evaluating the way they work or the way they fail to work in the classroom is one concrete way of doing this. Eisner’s concept of educational connoisseurship provides for a conscious examination of educational life that expands one's perceptual experience and relationship with what is learned (Eisner, 1985, p. 195). On the other hand, educational criticism discloses the qualities of an educational event so that one can ascertain its value (Eisner, 1985). Using these two dimensions, allows students to attend to the pervasive qualities of the classroom and to the latent cues communicated by teachers and students. For example, when students are encouraged to give creative written expression to their learning experience, the reader can participate more vicariously in their experience (Common, 1991: Kelly, 1989). Eisner's philosophical thrust provides a rich incentive for a renewal of teaching and learning. His use of educational criticism is consistent with social case studies although differing significantly from it in that students can critically reveal what they perceive and experience in the classroom dynamic itself. The use of the process recordings to analyze their interviewing skills as part of the course requirement speaks to these educational dimensions. V. Philosophical Orientations or Ideologies Toward Curriculum: An Eclectic Stance Each philosopher of curriculum has some aspects which are appealing (Passe, 1995). Consequently, it is possible to use a curriculum which incorporates features of different teaching philosophies. On average, teachers in their practice, for the most part, use modified aspects of the five orientations to curriculum. Some may tend to concentrate on one major orientation and others A New Perspective in Curriculum 14 may combine one or two of them. By considering the various aspects of these orientations or ideologies, a teaching course can have a philosophical base which is eclectic in nature. Teachers can actually plot out their own orientations as shown later in Figure 2. My own philosophical base for teaching has been eclectic and synergistic in nature and borrows systematically from the five major ideologies to curriculum with a strong emphasis with the self-actualization and personal relevance model. These are the five orientations which illustrate my own teaching profile. The first is the development of cognitive processes has its roots in process-orientated psychology and is seen by some educational theorists as ‘progressivism’ (Passe, 1995). It relates to Bloom's educational taxonomy which identifies six levels of operation: a) possession of information, b) comprehension, c) application, d) analysis, e) synthesis and f) evaluation. This taxonomy is similar to Figure 1 and represents increasingly complex cognitive processes. Cognitive processes, consistent with the ‘logic of discovery’, are generally considered to be introspective and problemcentered. Students define problems they wish to pursue and the teacher helps with the appropriate materials and guidance (Eisner, 1985, Miller & Morgan, 2000). This is particularly true as students identify problems encountered with clients in their field placement and appropriate corrections in terms of problem exploration and resolution are made as these matters are continually discussed in the classroom (Corey & Corey, 2002; Cournoyer, 2000; Miller & Morgan, 2000; O’Neil-McMahon, 1096; Toseland & Rivas, 19–). “Cognitive processes’ are incorporated in the classroom by the use of a teaching/learning contract where students identify what they still need to learn. This can be determined by the application of a pre-test or a pre-video tape interview to demonstrate what students know or do not know. The teacher as facilitator assists the students with the steps necessary for them to reach the goals and objectives which they have personally chosen as part of their initiation into the profession. For example, one student might contract to be more concrete and self-disclosing in the classroom. The teacher might model these two elements and invite students to use them in triads or small groups. In these small groups, the students are able to use their social work skills to understand and respond to one another and to specify any concern, confusion, anxiety or resistance that might be present. Following this group learning experience, they meet with the A New Perspective in Curriculum 15 larger class where any additional ambiguities or issues are clarified. Using this method, students are able to define and solve problems, locate relevant resources and evaluate the results of their efforts all under the sensitive guidance and knowledge of the classroom teacher. As a result, students are offered a first hand experience using their newly attained social work skills directly in the classroom. Through the use of cognitive processes, students are also taught how to learn, re-learn and un-learn. As a result, they develop an appreciation for the use of appropriate cognitive skills. This process promotes increased intellectual development and enhanced cognitive functioning and not just quantity of knowledge or regurgitation (Kelly, 1986). Students are seen as dynamic learners who have ultimate control over their destiny in terms of being more and more autonomous and more aptly prepared for social work practice. An emphasis is placed in the classroom on students learning what is actually taught by having them verbally communicate the content of the lecture material back to the instructor. In this way, if a few students understand what the teacher is teaching, then it can be assumed that these same number of students can then assist in teaching the remaining learners the same content. Such an approach can greatly diminish competitiveness and can increase a participative sense of learning community (Common, 1991; Kelly, 1989). According to Kelly (1989), ‘academic rationalism’ emphasizes the supremacy of the intellect over other human faculties independently of the information provided by the senses. It consistently returns to questions of social justice, the quality of the social order. Eisner (1985) sees academic rationalism, as dealing with ethical or normative determinants which is closely related to the goals and objectives of social work intervention (Cournoyer, 2000; Timberlake, et al., 2002). In this model the social worker has a responsibility for the people it serves. These important areas are discussed in class and students are given an opportunity to deal with them as these issues relate to their clients in their respective placement. Where the empiricist or the rationalists [we know what we know through the senses] postulate the supremacy of the intellect in perceiving knowledge independently of the information provided by the senses, an opposite view maintains that knowledge of the world and about us can be derived only though the use of our senses (Kelly, 1989). This brings us to the third orientation, self-actualization or personal relevance. This orientation calls for active learning as A New Perspective in Curriculum 16 opposed to the mere learning of facts (Eisner, 1985, Kelly, 1986). It takes into consideration the ideological stance of the teacher and the student (Kelly, 1989). Therefore, in order for the experience to be truly educational, students should have some say in setting up goals and in determining how they intend to be invested in the learning experience. It is essential that teachers establish rapport with students and realize how they actually see themselves when involved in the classroom. Unless teachers are able to visualize the character of the student's experience, there is a danger that they may relate to students as mere numbers on a list rather than as creative individuals who wish to expand the quality of their learning experience (Eisner, 1985). Following each class, students write down the goals they have set out for themselves, what they have accomplished during the week and how this has been helpful to them in their learning experience. They also communicate what they intend to focus on for the next week. It is here that they make comment or suggestions related to the course and the classroom process. The task of the professional educator is somewhat like that of a travel agent in providing a resource-rich environment whereby students will find what they need in order to grow naturally without having to be coerced. Teachers have an appreciable task on their hands in establishing rapport with students and in creating curricula that are geared to the aptitudes and interests of the learner. It is not sufficient for students to merely do what is expected of them in the classroom. Students need to realize the personal relevance of dealing with intellectual problems (Eisner, 1985). ‘Personal relevance’, a humanistic perspective, places emphasis upon personal interpretation and personal meaning. This is arrived at reflectively and dialogically by the student practitioner (Short, 1991). In terms of ‘personal relevance’, the course is designed so that students have an input in determining the personal significance the course will have for them. This provides them, within reason and the demands of professional practice and accreditation, an opportunity for enhancing, changing or delineating some aspects of the curriculum process. Education is seen in the original sense of the Latin word ‘educare’ which means ‘to lead’, ‘to guide’ or "to draw forth" (Buscaglio, 1982, p. 7). By her/his attitude, commitment and enthusiasm, the teacher can facilitate student learning. Students provide responsible, narrative accounts of their integration of social work theory and its application in the field practice A New Perspective in Curriculum 17 component. In other words, they have a voice in the internalization of the content and the practical application of theory as they field test it and return to the classroom to check out their learning efforts (Short, 1991). In addition, the assignments are individualized so that students can choose areas of personal relevance. Knowledge becomes educative only through its adaptation to the needs and the capacities of students. It is intent upon transforming the culture (Common, 1991; Kelly, 1989; Passe, 1995). Social work and social welfare is more allied with the fourth curriculum orientation of ‘social adaptation’ and ‘social reconstruction’ to the extent that it serves the interests of the people in the particular society in which it is engaged. In effect, the mission in this orientation is to locate social needs, to be sensitive to them, and, in turn, to provide the kinds of programs that are relevant for meeting the needs that have been identified, particularly, in relation to solving societal problems (Brueggerman, 1996; Eisner, 1985, Eisner, 1999; Passe, 1995). Students need to learn how to critically evaluate social issues and how to bring about constructive change. Social workers are not merely reinforcers of the status quo but also innovators of change. “Social reconstruction’ seeks largely to raise the consciousness level of students from a mediocre "status quo disposition" to providing or encouraging fundamental changes in basic structures of society. It presupposes an ethnographic grasp of our society at this particular point in time (Short, 1991). In this model, the curriculum is the vehicle for remedying such critical issues as drug abuse, sex education, race prejudice, environmental pollution, stress, community mental health, eugenics and the location of nuclear energy plants. It essentially determines the quality of the culture that students will inhabit. (Eisner, 1985, Eisner, 1999). Here the emphasis is on the questions social workers have to deal with. According to Eisner, it is not a matter of avoidance, by retreating to the abstractions of the academic disciplines, but rather a matter of using the knowledge provided by the academic disciplines as a tool for dealing with what is socially significant. The task of professional educators is to help social workers cope with the difficulties and issues raised by the professional in practice. Some educational theorists see curriculum as linear, or as a repetitive, step by step process (Bloom, 1956; Krotwoke, 1965; Passe, 1995; Wheeler, 1967). Others, such as Saunders (2000), see such skill training as a requisite component of courses offered in formal adult education 18 A New Perspective in Curriculum programs. This alternate view deals with essentially ‘proven knowledge’ or ‘practice wisdom’ which has been consistently used in the field of social work practice (Passe, 1995; Siporin, 1975). Such an approach is reflected in the fifth orientation, the ‘curriculum of technology’. This approach which is increasingly prevalent in our society, relates means to ends. It rests on determining: 1) what are the purposes and objectives of curriculum and 2) the developmental processes it wishes to promote (Blenkin, 1988; 1988; Blenkin & Kelly, 1987, Kelly, 1986; Kelly, 1989; Tyler, 1949). If the course objectives clearly state what students are expected to learn, then it should be relatively easy to implement the type of training necessary to achieve these goals. The learning here is sequential in that it builds upon the preceding material. It is also student reliant in that the stronger students can be a source of support for the weaker. Again, students in this model act as a co-operative community of learners committed to their own growth and learning, invested in their own learning, and assisting each other’s growth (Eisner, 1985). Here again, the ‘proof of the pudding’ (Bradley, 1985) is in the objective achievement of goals within a supportive teaching/learning environment and in Dewey’s own words: “making the ‘process’ and ‘goal’ one and the same thing” (Kelly, 1989, p. 91). Figure 2 identifies a curriculum profile that was developed by Patrick Babin, It graphically illustrates the level at which I use these orientations in my own teaching practice as they relate to content, goals and organization of the curriculum (Nephew, et al., 1979). This device allows a teacher to determine their orientation relative to content, goals, and organization of the curriculum. There are 57 questions which range from one orientation to the other. In terms of my own assessment of these ideologies, the ratings scores are almost identical for: Cognitive Processes (CP) = 9, Technology (T) = 9 and Academic Rationalism (AR) = 8. The Highest Rating Score is for Self-Actualization or Personal Relevance (SA) = 13. The lowest score is on Social Reconstruction (SR) = 6. Table II shows the following results: Insert Figure 2 Here VI Incorporating the Five Orientations and Ideologies–A Creative Synthesis A New Perspective in Curriculum 19 Curriculum can be substantially improved by integration and synthesis (Passe, 1995). According to Eisner (1985), the five ideologies are seldom encountered in their pure form, although one of the five views does usually dominate. This can be seen by doing one’s own profile. Each orientation, Eisner contends, is justified on the basis of professional judgment which is achieved by reflecting upon one’s own practice and by considering what research has to say about practice. Having considered the five orientations to curriculum, I will conclude with my own creative syntheses, a method which “...attempts to critically examine and integrate specific points of view into new wholes” (Shostrom, 1979, p. xxii). In this model, a teacher can adopt or apply whatever THEY consider useful or facilitative to teaching and learning. As a personal example, I have attempted in my own professional development to integrate various teaching and learning approaches in order to create a blended and creative synthesis. Specifically, I have made use of various principles taken from the works of Freud, Adler, Frankel, Curran, Maslow, Shostrom, Egan, and Carkhuff and Berenson. Freud stressed man’s will to pleasure. I have sought to make the adult learning experience enjoyable or pleasant. Adler based his approach on a person’s will to power. Since adults are often overwhelmed or helpless in their new learning environment, I have tried to provide them with a sense of power, empowerment or accomplishment. It is important to assist students in working through the confusion which arises when horizons are extended and when their boundaries and perception of the world are being threatened. Victor Frankel emphasized a person’s will to meaning. “What keeps us going is the recognition that we have meaning and purpose in our lives” (Timberlake, Farber & Sabatino, 2002).Though an adult may experience life as being without value, each person invariably searches for a sense of meaning and purpose in their lives. Students thus strive for integration and resolution in their learning and look upon the teacher to aid them in this process. I also take from Sullivan’s spirit of consensual validation, Shulman’s emphases on the importance of a ‘symbiotic relationship’, and Eisner’s inclusion of ‘logical discovery (Blachowich, 1998; Miller & Morgan, 2000). Curran (1976) addresses a person’s will to community where teachers and students are both seen in their total personalities, deeply engaged together in the learning process. This aspect of my own teaching philosophy is based upon the relevance of ‘personal meaning’ for the student (Eisner, 1999). My application of a creative synthesis builds also upon the humanism of A New Perspective in Curriculum 20 Abraham Maslow and the actualizing process of Shostrom wherein adult students are encouraged to fully explore the depth of their strengths as well as their weaknesses. I attempt to help students to discover their untapped potential. In this, like others, I encourage students to recognize their own strengths and liabilities. (Common, 1990; Shostrom, 1976, p. 302). According to Rogers, the authority which the professor has to teach rests upon certain attitudinal qualities which exist in personal relationship between the facilitator and the learner (Common, 1991). The work of Carkhuff and his associates bring a blend of the person-centered approach of Carl Rogers and the learning by objectives of the behaviorists. The Carkhuff model places emphases upon the basic concepts of empathy, respect, genuineness, concreteness, selfdisclosure, self-exploration and confrontation. I attempt to be available to the deepening experience of students, and to provide incentive which can enable learners to move from where they are at the beginning of the term, (point A), to where they want to be at the end of the term, (Point B). I also try to aid students in identifying the necessary steps needed to move from A to B. Here, the adult student is viewed as a gestalt configuration of physical, emotional, intellectual and experiential components (Carkhuff & Anthony, 1979; Egan, 1998) To paraphrase Shostrom (1976), in his reference to Assagioli, a creative synthesis must be geared to the existential moment. Who the teacher is, what is going on at the moment, and where in the total process of teaching and learning, both instructor and student are, all contribute to the existential decision on a thinking, feeling and doing bases. Emotive language in the classroom engages the senses and the emotions thus enabling the personal or idiosyncratic understanding of subject matter, events and interactions. It is a process which provides the opportunity to internalize one’s learning experience by owning it as one’s own and putting the new – and knowledge to work in one’s professional practice (Common, 1991). It is the ‘educable moment’ where the cognitive, affective, behavioral and experiential components of learning come to life and have their fruition in a ‘new social work self. By sharing this new-found knowledge and experience with the instructor and the other students, the teaching/learning climate is enhanced and magnified and the student is transformed beyond the mere ‘grasp’ of knowledge or the mere ingestion of ‘cerebral level’ content which often leaves a learner isolated and disengaged. I have systematically applied insights from Curran’s (1976) teaching/learning research 21 A New Perspective in Curriculum which he conducted at Loyola University. Curran had discovered basic elements that are essential to individualized learning and he grouped these elements under the acronym SARD, four letters with six implications...SECURITY, ATTENTION-AGGRESSION, RETENTION- REFLECTION and DISCRIMINATION. A feeling of security empowers the student to a sense of openness. This in turn, determines a great deal of the actual level of investment to the plan that will be applied to learning. Attention is imperative to avoid boredom and guilt. Learners need to assert themselves and to learn aggressively. Thus, it is important that they be convalidated and supported by a participative community which includes the teacher and the other students (Kelly, 1989). In this way, students experience a balance between the forces of self-assertion on one hand, and the need to belong on the other. Retention is important for later use. By responding and reflecting the learning content, students increase their retention ability. Discrimination is necessary if students are to accurately identify the major concepts and the required skills (Curran, 1976). Students need to learn a suitable way to assimilate their new knowledge in social work so that they can internalize this material in an informed way–one that can be effectively operationalized in their beginning practice. Indeed, students learn best in an interactive format which has a heavy emphasis on their day to day experiences and on the practical application of their learning (Tweedell, 2000). Students are encouraged to discover their own personal significance to the learning experience. By the use of an insemination-germination model to teaching/learning, students are helped to ‘flesh out’ and ‘give life’ to their new concept through the use of an interior informational type of process (Curren, 1976). In this agrarian model, the teacher who has sown the seed of learning now provides warmth and security for the student providing a receptive soil bed. The teacher is also the knower who instills the seed of knowledge within that student. The student, in turn, is now able to make an act of trust in the teacher-knower, as she/he attempts to understand and integrate this new knowledge with further help from the teacher, thus giving birth to a new social-work-self. In this whole-person orientation to education, students can accept responsibility for their own choices and can be rewarded in a supportive fashion through the reassurance and guidance of the teacher and the gains that are made in their professional development. What occurs is somewhat similar to Sullivan’s concept of consensual A New Perspective in Curriculum 22 validation wherein students feel prized and valued in their uniqueness and are further motivated to risk exploring at deeper level of growth and maturity. What is evidenced here is a synergistic and symbiotic relationship where students can uniquely operationalizes the knowledge they have internalized concerning social work intervention. In this way, learning is integrally related to the real life experiences of students. VII. Student Responses to the Classroom Teaching/Learning Experience What do students have to say about the teaching/learning model that they experienced? By taking a close look at student feedback, further implications can be drawn for enhancing the human learning experience. The replies of students seem to indicate, for the most part, a rather favorable response to the essential elements of teaching and learning. The less favorable comments offer incentive for further androgogical improvement. The comments which follow outline a summary of student feedback. Following each class students are asked to write any comments about the teaching./learning experience and to offer any suggestions as to areas they would like to see changed or modified. In addition, in the final class, students are given a questionnaire which they are asked to complete anonymously. The results are given to the social work secretary and are not opened by the instructor until the final grades are officially posted. 1. Favorable Feedback The warmth and openness of the instructor fostered a climate that encouraged the active participation of students and contributed to meaningful growth and professional development. It kept my interest alive and really made me think and learn. Because of his teaching style, and considering that I am a rather shy person, I have “come out of my shell” and I am confident in my ability to use in my social work practice the knowledge and skills I gained from this course. By using the A to B format, the instructor effectively modeled the skills of listening, attending, understanding, responding, assessment and problem-solving, all of which we need as social workers. It was very much a mutual exchange and a very meaningful encounter. We were reinforced in our journey by the caring guidance and expertise of the teacher. Through use of the contract, we were challenged to take a good, hard, honest look at ourselves and to recognize areas which required our attention. It made me take responsibility for myself, A New Perspective in Curriculum 23 and not leaving the onus strictly on the teacher. The goals the teacher set - to provide the nutrients of knowledge, support and caring to students - were clearly attained. This nurturance took place not only in the classroom but extended into his office, the hallway, or wherever the situation arose where he instinctively knew a student was in need. It was through his "availability" that many students were able to look into themselves, and begin to grow in the direction the student felt necessary. This approach could serve as a model for other social work professors who are searching for a way to teach ‘humanness’ in the classroom. This teaching/learning model recognizes the value and significance of the facilitative skills between teacher/student, student/teacher and student/student within the classroom. He genuinely communicates the real worth of the student/learner by fostering his or her growth through the understanding of their needs and feelings which result as part of the learning experience. This class has provided me with a deeper awareness of the dynamics which occur in human interaction, and has given me a stronger ‘skill’ base for effective intervention. I have never had a class like this before. I am use to sitting and taking note after note while listening to the teacher ramble on about something which is suppose to have relevance but at the time really means nothing because I am so busy trying to get it all down on paper. In this class, we were challenged to think “outside the box”, to be creative and to be expressive of our true selves. I always left class with such a ‘great feeling’ that I couldn’t wait for the next class to occur. I find it difficult to put into words exactly how this class has affected me, but I do know that I have been altered in a tremendous manner, both personally and professionally, beyond what any textbook could report. This alternate approach to learning was a challenge from the cerebral learning which has dominated my elementary, high school and university years. For the first time, I have come to know ‘experientially’ and I prize as a treasure knowledge which I will never forget. The sharing community has given me the opportunity to trust, to confide and to grow with my fellow classmates, and most of all to understand what it means to ‘learn with my heart’. A New Perspective in Curriculum 24 Less Favorable Responses Too structured; expectations too high. Though there is room for discussion, there is little or no room for arguments in this model. The triads require closer supervision or teacher monitoring to ensure their effectiveness as a training tool. Social work students are a strange breed; they work so hard to express and experience feelings and process outside the classroom, but inside the class they put that effort to rest. It is difficult for students who are used to being passive recipients of content in most other courses to become dynamically engaged in the personal and professional demands of the ‘human’ classroom and ‘humanistic’ learning. This model calls for self-awareness which is often avoided in other classes This aspect does not come easy and therefore, the ego defenses of students are sometimes higher. Too risky to respond in front of all the other students because it will be looked upon by other students as patronizing the instructor. Students often reject this type of model because it requires total self-investment which is often a demanding and somewhat painful experience. As much as the instructor provided positive support in and outside of the classroom, in order for students to effectively overcome their resistance to learning, they must make an effort be committed to personal growth and professional development as ‘budding’ and ‘accountable’ as social workers. Nothing changes if we are not encouraged to ‘really’ work. Some students are unaware of what social work entails in the ‘human’ classroom. The students must understand that the reality which confronts them in the human classroom is part of the reality that will confront them in the field – a invaluable experience that will give them workable skills in helping clients. I know what you're doing in terms of teaching within a holistic context, and though it is really good and I very much appreciate it, nonetheless, when you stop and think of it, we have some twenty years of hard-nosed ‘traditional schooling’ behind us which hampers our movement A New Perspective in Curriculum 25 from this comfortable nest. You are running up against resistance, closed-mindedness, which reinforces intellectualism and prevents students from internalizing the concepts of the ‘human’ classroom. The classroom calls for more honesty than some students are prepared to give. Because of the uniqueness of this model and the growth-struggle entailed in learning it is almost inevitable that some students will reject this teaching method as new experiences often create undue anxiety which can lead to rejection of the new and unfamiliar experience and students are unwilling to risk the new experience for greater professional gain . VIII Implications and Suggestions for Educators There are, as can be expected of any innovative approach, both positive and negative responses to this proposed model. Ultimately, the most important thing is that the instructor remain open and receptive to the feedback of students. The measure of effectiveness lies in the student's ability to derive personal meaning from the learning experience so as to enhance his/her professional competence. To facilitate student learning using this model, it may be useful to provide a summation of the philosophy and teaching style entailed as an aid in clarifying and modifying course objectives and processes. The use of Flander's Interaction Matrix Analysis could help to determine the strengths and weaknesses of instruction (Eisner, 1985). It would also be helpful to administer a cognitive map to determine the unique learning style of each student (Hill, 1981) and to further personalize their learning by adapting the approach which seems to conform to the majority of the students without compromising the substance of the instructor’s own ideology. The following are a few suggestions for educators. We must continue to examine in a critical fashion the justification of the curriculum orientation/s we choose and determine the effectiveness it has for students in personalizing their learning experience. We must continually evaluate the effectiveness of an eclectic approach to curriculum and borrow from the new developments in the field of curriculum and design. Continue to check the reactions of student as to the instrumental quality of the teaching/learning experience and to consider valid responses that will help change the face A New Perspective in Curriculum 26 of learning by adapting new techniques and processes. IX Concluding Remarks It is hoped that this paper will spark a renewed interest in reevaluating ones own educational experiences so as to improve curriculum building. What is offered then, by way of challenge is for educators to risk a more encompassing orientation to curriculum which takes into consideration the needs of both the teacher and the student in the educational enterprise. In sum, this paper has provided a beginning androgogical framework for an integral understanding process to occur in the teaching/learning encounter. The understanding concept, reflective of a counselling-learning type modality is quite consistent with the fundamental knowledge, values, and skills of social work practice as applied systematically and dynamically in the classroom. Although the discussion of this article has been limited to the intervention sequence, these ideas and principles can be applied to all courses in the social work curriculum. Social work educators have an unprecedented opportunity to enhance and to foster the taskoriented learning experience of students. It is hoped that the ideas presented will in some small way, prove to be a source of illumination in social work education and will prompt faculty to reexamine their traditional approaches and values toward teaching and learning. In this way, potential social work professionals will be exposed to an educational endeavor which is both challenging and rewarding. Further work needs to be done in order to more clearly define, evaluate and transmit this proposed educational design for social work. The ultimate measure will be student learning. Finally, this paper has presented a fresh, innovative, humanistic, whole-person model which engages the social, intellectual, emotional and somatic capacities of both the teacher and the student. A plea has been made for the incorporation of a counselling-learning type modality which has been gleaned from the insights of social work and other related disciplines such as psychology and education. As social work educators, and as educators in general, we cannot afford to rest on our laurels as we must be innovators of our educational enterprise. This paper has provided an eclectic and synergistic teaching and learning approach. I have given an indication of some influential literature in the field of education and social work, a brief examination of my own (what has guided me throughout my 30 years of teaching) approach and A New Perspective in Curriculum 27 its implications for social work curriculum building. This paper, hopefully, will encourage social work educators to reexamine their own teaching and learning approach in light of new insights gleaned from professionals and educational leaders in the field. Finally, in terms of social work education, we would like to paraphrase one simple caveat suggested by Eisner (1998), when he advises that sometimes it may just be better not to give customers what they want but, instead, to help them understand what they ought to want. This is in no way paternalistic but is consistent with the rigour and demands placed upon the accreditation demands of required to practice social work and the stictuativeness and perseverance required of each student to meet the demands necessary for the accomplishment of this criteria of competence. As teachers, it is our task to help students interpret from our own expertise what social work education, or any form of higher education for that matter, is all about but perhaps more importantly, in the conviction of Alfred North Whitehead, that no matter what approach we responsibly take in our legitimate attempt to teach students, ‘the joy is in the journey’ (Eisner, 1999). 28 A New Perspective in Curriculum References Babin, P. (1979). New realities in education, curriculum orientation. In curriculum Canada by J. Nephew, C. J. Ball, I. Crawford, Lexington VI: Ginn and Company. Biestek, F. (1957). The casework relationship. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Blenkin, G. (1988). Education and development: Some implications for curriculum in the early years. In W.A.L. Blyth (ed.). (1988). Informal primary education today: Essays and studies. Falmer, London. Blenkin, & Kelly, (1987). The primary curriculum in action. (2nd Ed.). London: Harper & Row. Bradley, L. H. (1985). Curriculum leadership and development handbook. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall Inc. Buscaglio, L. (1979) Living, loving and learning. New York: Ballentine Books Carkhuff, R. & Anthony, W. (1979). The skills of helping. Amherst, MA: Human Resource Development Press. Clemence, E. H. (1965). The dynamic use of ego psychology in casework education. Smith College Studies in Social Wo rk. 35(3), 157-172. Common, D., (1991). Curriculum design and teaching for understanding. Toronto, ON: Kagan and Woo Ltd., Lakehead University. Curran, C. A. (1972. Counselling-learning: A whole person model for education. New York: Grune and Stratton. Curran, C. A. (1976). Counselling-learning in second languages. Apple River, IL: Apple River Press. Eisner, W. E., (1985) The educational imagination: On the design and evaluation of school programs. (2nd Ed.). New York: MacMillan Publishing Co. Eisner, E. W. (1994). Cognitiion and curriculum reconsidered. (2nd Ed.). New York: The College Teachers Press, Columbia University. Eisner, E. W., (1998). Does experience in the arts boost academic achievement? Arts Education Policy Review 100(1), 32-8.. Eisner, E. W. (1999). Performance assessment and competition. The Education Digest.65(1) A New Perspective in Curriculum 29 54-8. Gallant, W. A. (2002). A striking parallel between social work education and practice. (Manusript). Windsor, ON: Jewel Max Press. Gitterman, A. (1972) Comparison of educational models and their influences on supervision. In Issues in human services. By F. Whiteman, Kaslow and Associat es. San Francisco: Jossey/Bass Inc. Schwartz, F. (1961).”The social worker in the group.” In New perspectives on service to groups: Theory, organization, practice. Pp.7-34. New York: National Association of Social Workers. Schulman, L. (1999). The skills of helping: Individuals, families and groups.(4th Ed.). Itasca, IL: F.E. Peacock Publishers, Inc. Kelly, A. V. (1986). Knowledge and curriculum planning. London: Harper & Row. Kelly, A. V., (1989) Curriculum: theory and practice. London, England: Paul Chapman Publishing Ltd. Knowles, M. (1972) Innovations in teaching styles and approaches based on adult learning. Journal of Education for Social Work. 8(2), p. 32 Miller, S., & Morgan, R. (2000). Establishing credibility of alternative forms of data representation. Educational Studies 31(2) 119-31. Nephew, C., Ball, I. Crawford, I., (1979). Curriculum Canada. (Edited). Lexington: VI: Ginn and Company. Passe, J., (1995). Elementary school curriculum. Boston: McGraw-Hill College. Rothman, B. (1973). Perspective on learning and teaching in continuing education. Journal of Education for Social Work, Spring. Short, E. C. (1991) Forms of curriculum inquiry. Albany: NY: State University of New York Press. Siporin, M., (1975). Introduction to social work practice. New York: Macmillan. Smith, O. E., Goodman, K. S., Meredith, R. (1976) Language and thinking in school. (Second Edition). New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston. Timberlake, E., Farber, M., Sabatino, C., (2002) The general method of social work A New Perspective in Curriculum 30 practice: McMahon’s generalist perspective. Boston: Allyn & Bacon. Towle, C. (1954). The learner in education for the profession. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press Tyler, R. W. (1949).Basic principles of curriculum and instruction. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. 31 A New Perspective in Curriculum Figure 1 A Comparative Chart of Three Dimensions of Teaching and Learning Smith, Rothman & Goodman & Towle Gallant Meredith Perceiving Knowledge Thinking Understanding First Contact is Knowing Social Work Knowledge, Course Content and Classroom Through the Values, Attitudes and Skills Material Senses Where Uniqueness of the Teacher Student Receives Uniqueness of Each Student New Data Knowledge Distortion Calls False Interpretations Calls for Misunderstanding and Intellectual for Appropriate Information on Behalf Blocks Call for Re-presenting Confrontation of Teacher and Student Content and Facilitating Cognitive Resistance to Learning New Material Values Ideating Feeling Integrating Intellect and Emotional Development Personalized Learning Feeling of Student, Pulling Together the Dimension are Individualized Learning, and Knowledge Gained Stimulated by Energy Level the Need to Know Values The Teacher Teacher Provides for Teacher Provides Optimal Provides a Student Growth by Reducing the Opportunity for Meaningful Process Stimulating Ego’s Mechanism to Occur Environment of Defense and Emotional Blocks to Learning 32 A New Perspective in Curriculum Skills Presenting Doing Operationalizing Symbolically Using the Knowledge, Skills and Effectively Putting into Practice the Representing on Values of Social Work and Testing Knowledge, Values and Skills of One’s Own These for Practical Use in the Social Work Practice Uniquely Terms Concepts Classroom Teaching/Learning Learned in the Supportive to Others for Experience and in the Field Practice Teaching/Learning Environment Feedback Component 33 A New Perspective in Curriculum Figure 2 Curriculum Orientation Profile Rating Orientation Dimension CP T SA Rating SR AR 13 13 12 12 11 11 10 10 9 9 8 8 7 7 6 6 5 5 4 4 3 3 2 2 1 1 CP T SA SR AR A New Perspective in Curriculum CURRULUMBLDlarge.wpd///DATE \@ "MMMM d, yyyy (h:mmAM/PM)" 34 A New Perspective in Curriculum 35