Restricted, repetitive and stereotyped patterns of behaviour, interest

advertisement

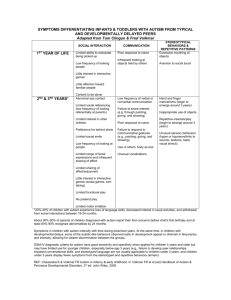

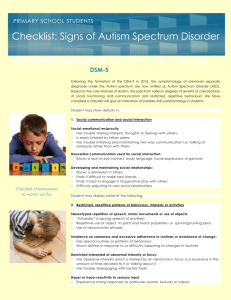

Restricted, repetitive and stereotyped patterns of behaviour, interest and activities Dr. Avril V. Brereton Part One: Managing special interests in children with autism “Obsessions”, “circumscribed interests”, “special interests”, “routines”, “rituals” , “preoccupations” are some of the terms used when describing the behaviour of children with autism. These behaviours belong to one of the three core areas of impairment in children with autism. To put these behaviours in perspective it is helpful to go back to diagnostic criteria and consider the three core areas affected in children with autism. According to DSM-IV-TR (2000) these are: 1. 2. Qualitative impairment in social interaction Qualitative impairments in communication And the area this fact sheet is concerned with3. Restricted, repetitive and stereotyped patterns of behaviour, interest and activities, as manifested by at least one of the following: a. encompassing preoccupation with one or more stereotyped and restricted patterns of interest that is abnormal either in intensity or focus. b. apparently inflexible adherence to specific non-functional routines or rituals. c. stereotyped and repetitive motor mannerisms e.g.: hand or finger flapping or twisting, or complex whole-body movements. d. persistent preoccupation with parts of objects. Special interests or obsessions fit into this third area of “restricted, repetitive and stereotyped patterns of behaviour, interest and activities”. Children must have at least one of the symptoms from this area of impairment, together with symptoms from the other two areas for a diagnosis of autism to be made. So young children with autism may have preoccupations, and/or non-functional routines or rituals and/or motor mannerisms and/or preoccupations with parts of objects. Some children with autism may present with all of the symptoms in this core area while others may have only one or two. Recent research suggests that these symptoms are more likely to occur after about three years of age. Because autism is a developmental disorder, symptoms will change over time and with age and development. What is important is that with each of these symptoms, there is a descriptive word used to emphasise that we are not talking about occasional odd interests or odd movements. These are “encompassing” preoccupations, “apparently inflexible adherence” to routines and rituals, “repetitive” motor mannerisms, and finally, “persistent” preoccupation with parts of objects. All young children can have favourite toys and activities, and favourite topics of conversation, but for the child with autism, these interests become intense and focussed to a degree that exceeds what is expected in typically developing young children. Some children will move from one obsession to another and the obsession may last for weeks or months before it changes. Others may develop an interest, for example, in trains and Thomas the Tank Engine in early childhood and continue with this interest through adolescence and into adulthood. Below is an illustration by a teenager with autism who at three years of age would only play with his Thomas trains and only wear Thomas clothes. You can see that the train obsession has continued and he now draws complex pictures of railway sidings, trains and railway crossings. Autism Friendly Learning: Restricted, repetitive and stereotyped patterns of behaviour, interest and activities 1 Attending Visual thinking. What can we do to manage special interests and obsessions? Why do children with autism develop special interests and obsessions? Recent research is helping us to understand how children with autism think and learn. The findings of brain imaging studies are pointing to problems in several areas of the brain. For example: increased brain volume but decreased grey matter in the limbic system (social cognition and emotions); Reduced neurons in cerebellum (motor) and parietal lobes (attention); Abnormalities in prefrontal cortex (executive function) and fMRI decreased activity in fronto striatal circuits (executive function). These brain anomalies affect emotions and behaviour. For example, we know that some children with autism have difficulty moving from one task or activity to the next. They are unable to move the focus of their attention – they get stuck and cannot shift their attention easily. This might be perceived as being obsessed with an activity or thought but may also be explained by problems with weak central coherence (inability to integrate detail into the whole). Poor executive function (the ability to plan, time, adapt behaviour to act appropriately and with relevance to a situation) may explain why some children are rigid and inflexible and would prefer to follow strict routines. These behaviours may also occur when children are excited or anxious. Some of the problems children with autism have with thinking and learning Difficulty seeing cause and effect relationships Focus on details Difficulty sequencing Difficulties with understanding of time Compulsiveness Distractibility When discussing obsessions in autism, the term 'obsessions' is used narrowly, to indicate strong, repetitive interests. First there needs to be some thought as to how much of a problem the obsession or special interest is for the child and also the family and others such as teachers or therapists. The rule of thumb when making decisions about whether or not to intervene or change behaviour (including special interests or obsessions) is to ask yourself: Does the behaviour endanger the child or others? Does the behaviour increase the likelihood of social rejection or isolation? Does the behaviour interfere with or preclude participation in enjoyable activities and an education programme? Will the behaviour be acceptable in 5 years time? In young children with autism, obsessive and special interests are most likely to be judged inappropriate because they fall into the third scenario and interfere with learning new skills and participating in educational programmes. Removal of obsessions is unwise and rarely successful. Take an existing obsession away and a new one will appear that may be worse than the one you removed so care needs to be taken. Early intervention and response to obsessional activities is recommended because the longer an obsession continues, the more entrenched it becomes and more difficult to reduce. Management, limitation and control These are better than trying to remove obsessions. Gradual change will also be less distressing for the child. This should be done gradually with an emphasis on teaching new skills or play activities. Time Set clear consistent rules about when and where obsessional activity is allowed and when is it not. Photographs or simple behaviour scripts, timetables and first-then strategies can be helpful. An oven timer that shows time passing can be used when setting limits on the time spent Autism Friendly Learning: Restricted, repetitive and stereotyped patterns of behaviour, interest and activities 2 talking about topic/activity. or playing with a favourite Object Limit the amount of a preferred object the child may have. For example: Leave the Thomas trains in the school bag; Rock collection stays in the car when Mum drops child at school. Shared activities You may find that you can develop some shared activities that utilize obsessions and special interests. For example, play trains together for a set time during the day or evening before bed; go to the library together to find books about the special topic of interests and look at them together. Consistency You must be consistent across settings and people when introducing management of obsessions. It is very confusing for a young child with autism if limits are different depending on where and with whom he/she is. References Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision (DSMIV-TR), (2000) American Psychiatric Association. Marjorie H. Charlop-Christy and Linda K. Haymes (2004) Using Objects of Obsession as Token Reinforcers for Children with Autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 28, 189-198. Ami Klin, Judith H. Danovitch, Amanda B. Merz, Fred R. Volkmar (2007) Circumscribed Interests in Higher Functioning Individuals With Autism Spectrum Disorders: An Exploratory Study. Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities, 32, 89-100 National Autistic Society UK “Obsessions, repetitive behaviours and routines” http://www.nas.org.uk/nas/jsp/polopoly.jsp?d= 1071 anda=7103 Remember obsessions can be used as rewards to increase new behaviours and teach new skills There is an “upside” to obsessions and special interests. They can be used as rewards and motivators to teach new skills and behaviours. Studies over the past twenty years have been reporting the successful use of objects of obsession rather than only using the more usual reinforcers such as stickers, food and stars to reward on task performance, and to decrease inappropriate behaviours during work and play sessions. Some special interests also provide a source of enjoyment for young children who have limited play skills. If the obsession is not dangerous, to the child or others, intruding on learning opportunities or excluding the child from social opportunities it’s probably OK to let it go. Autism Friendly Learning: Restricted, repetitive and stereotyped patterns of behaviour, interest and activities 3 Part Two: Managing routines, rituals and repetitive motor mannerisms “Obsessions”, “circumscribed interests”, “special interests”, “routines”, “rituals”, “preoccupations” are some of the terms used when describing the behaviour of children with autism. These behaviours belong to one of the three core areas of impairment in children with autism. To put these behaviours in perspective it is helpful to go back to diagnostic criteria and consider the three core areas affected in children with autism. According to DSM-IV-TR (2000) these are: 4. 5. Qualitative impairment in social interaction Qualitative impairments in communication And the area this fact sheet is concerned with6. Restricted, repetitive and stereotyped patterns of behaviour, interest and activities, as manifested by at least one of the following: a. encompassing preoccupation with one or more stereotyped and restricted patterns of interest that is abnormal either in intensity or focus. b. apparently inflexible adherence to specific non-functional routines or rituals. c. stereotyped and repetitive motor mannerisms e.g.: hand or finger flapping or twisting, or complex whole-body movements. d. persistent preoccupation with parts of objects. Adherence to non-functional routine or rituals and stereotyped and repetitive motor mannerisms fit into this third area of “restricted, repetitive and stereotyped patterns of behaviour, interest and activities”. Children must have at least one of the symptoms from this area of impairment, together with symptoms from the other two areas for a diagnosis of autism to be made. So young children with autism may have preoccupations, and/or non-functional routines or rituals and/or motor mannerisms and/or preoccupations with parts of objects. Some children with autism may present with all of the symptoms in this core area while others may have only one or two. Recent research suggests that these symptoms are more likely to occur after about three years of age. Because autism is a developmental disorder, symptoms will change over time and with age and development. Why do children with autism do these things? Some young children with autism develop a resistance to, or fear of, change that then involves being rigid in their approach to their surroundings. Insistence on sameness, routines and rituals begin. Certain items must be placed in particular places and not moved. Objects may be stacked or lined up in a repetitive manner. Certain routes must be followed to and from familiar places. Particular cutlery and crockery must be used or the child refuses to eat or drink. Perhaps confusion coping in a world that is overwhelming is the cause of this behaviour, so the young child with autism responds to this uncertainty by being in control of what they can...usually their immediate environment, the objects in that environment and also the people in it. Repetitive motor mannerisms may occur when some children are excited, anxious, or worried. For others, sensory sensitivities and physical enjoyment may drive repetitive jumping, arm flapping, twiddling of fingers in front of their eyes and covering ears and eyes with their hands. It must be said that repetitive behaviours/mannerisms in autism is a somewhat neglected area of research. In the past, these behaviours were associated with lower levels of functioning and repetitive motor mannerisms are also seen in children with intellectual disability who do not have autism, so we cannot say they are particular to children with autism. These behaviours were also thought to increase during the preschool years. There is now some evidence that repetitive motor mannerisms develop differently to insistence on sameness and these behaviours follow different trajectories over time. Richler et al, (2008) concluded that restricted and repetitive behaviours “show different patterns of stability in children with ASD, based partly on the ‘subtype’ they belong to. Young children with low NVIQ (non verbal IQ) scores often have persistent RSM behaviours (motor mannerisms). However, these behaviours often improved in children with higher nonverbal IQ (NVIQ) scores. Many children who did not have IS behaviours (insistence on sameness) at a young age acquired them as they got older, whereas children who had these Autism Friendly Learning: Restricted, repetitive and stereotyped patterns of behaviour, interest and activities 4 behaviours sometimes lost them. Trajectories of IS behaviours were not closely related to diagnosis and NVIQ.” What should we do about routines, rituals, and repetitive motor mannerisms? First ask yourself the question “How much of a problem is it?” and ”Who for?” The answer is often that these behaviours are a problem for parents/carers, teachers and therapists rather than the child him/herself, who is quite happy to be preoccupied in these ways. Therefore, it is unlikely that the child will want to change his/her behaviour! The rules of thumb when making decisions about whether or not to intervene or change behaviour are to ask yourself: Does the behaviour endanger the child or others? Does the behaviour increase the likelihood of social rejection or isolation? Does the behaviour interfere with or preclude participation in enjoyable activities and an education programme? Will the behaviour be acceptable in five years time? In young children with autism, adherence to nonfunctional routines and rituals and displaying repetitive motor mannerisms may be judged inappropriate because they fall into one or more of these categories, or may be tolerated by the family and others and are not seen as problematic. Let me give some examples: Behaviour - Repetitive pacing “Andrew” (5 years) paces the fence line in the back yard of his home for about one hour every time he arrives home from school. This is the only time he paces like this and he was able to tell his parents that it makes him “feel good” when he does this. He is able to come inside and get on with the rest of his day after this pacing. For “Andrew” it seems that this repetitive pacing is necessary for him to calm himself after the social demands of attending the busy school environment. His family decided that this was OK and felt they did not need to stop the behaviour because it occurs in the privacy of his own home and does not interfere with anyone else. Behaviour - Repetitive pacing “Billy” (6 years) was constantly flicking his ears with his fingertips. He has made them bleed with the frequency of the flicking. He did not seem distressed about this, but his family and others were. It was unclear as to why “Billy” was doing this and he generally under reacted to pain so it was not thought to be a sensory issue. A general assessment of his learning, communication and play skills revealed that he had a developmental delay, no functional speech and very few play interests. Observation over one week found an association between “Billy” wanting something and the ear flicking. He would stand beside an adult and flick his ears. Management included slowly introducing some photographs of desired objects (usually food). “Billy” learned to use these to make requests and as this communication skill increased, the ear flicking decreased. Behaviour - Rituals and routines (Shopping aisles) “Tamsyn” (4 years) enjoyed shopping in the supermarket with her parents and always wanted to go on this outing. However, when they arrived she would scream if her parents did not go down every aisle in the supermarket starting with aisle number 1. She would read the number and then direct her parents down that aisle. At first the family thought it was “cute” that she could read numbers but this behaviour became very problematic when the shopping trip extended into a very long activity. They could not skip the aisles they did not need to buy anything in or “Tamsyn” would throw herself on the ground and scream. Other shoppers pointed and stared or told the parents “She needs a good smack.” It was decided that change would be introduced gradually to decrease this routine. At first, shopping was limited to going to buy one item. Before going out, it was explained to “Tamsyn” that mum would be buying “milk today”. She was shown a photograph of the type of milk that would be bought and “Tamsyn” knew the aisle number for that item. A simple behaviour script with photographs was prepared and read before the shopping trip. “Car, shop, milk, home”. Tamsyn” also took this with her. Very simple instructions, consistency, use of a reward for “good shopping” and a gradual increase in items to be bought worked to change this rigid routine. (While this was happening, mum and dad did most of the shopping when “Tamsyn” was at child care!) Before developing a response or management plan to deal with restricted, stereotype behaviours it is essential to gather the following information about the child’s: Autism Friendly Learning: Restricted, repetitive and stereotyped patterns of behaviour, interest and activities 5 current profile of autism symptoms, developmental level, communication skills, preferred activities (possible use of these as rewards), and Careful observation of the child to find out when and where restricted, stereotype behaviours occur and whether there are any triggers to the behaviour. Further reading Emma Honey, Helen McConachie, Val Randle, Heather Shearer and Ann S. Le Couteur (2008) One-year change in repetitive behaviours in young children with communication disorders including autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders , 38, 1439-1450 Richler, J., la Huerta, M., Somer L., Bishop, D. & Lord, C. Stability of Individual Restricted and Repetitive Behaviors in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders. The International Meeting for Autism Research (London, May 15-17, 2008) Autism Friendly Learning: Restricted, repetitive and stereotyped patterns of behaviour, interest and activities 6