diabetes-toolkit-links-updated-v3-feb08

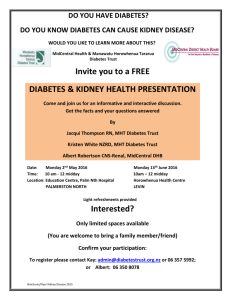

advertisement